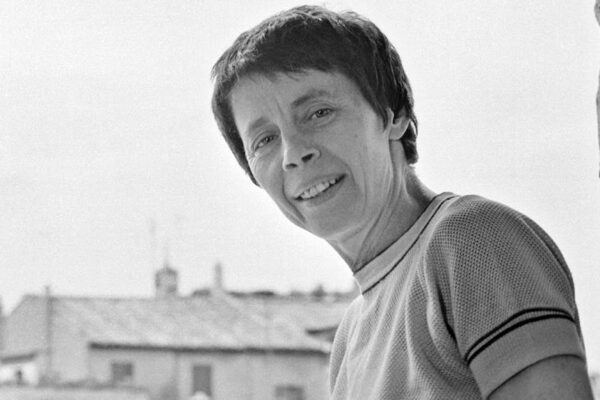

Dan Friedman, contributing editor of Sources. Originally published in "Sources: A Journal of Jewish Idea” Fall 2021. Reposted by permission. Image: Kelly Writers House.

Peter Cole is one of the foremost Jewish poets and translators in the English-speaking world. Born in 1957 in Paterson, New Jersey, for much of the past four decades he has lived in Jerusalem.

He is the author of five books of poems and many volumes of translation from Hebrew and Arabic. Cole’s most recent collection, Hymns & Qualms: New and Selected Poems and Translations, was published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 2017. He had a chapbook out last year, On Being Drawn, a collaboration with artist Terry Winters, and a new poetry collection, Draw Me After, is forthcoming next year (also with FSG). Though Covid has kept him in New Haven—he teaches at Yale each spring—he has had a highly productive pandemic. Since before Covid struck, he has been co-writing an oratorio with Pulitzer Prize winning composer Aaron Jay Kernis. Even while locked down, he continued teaching at Yale and co-editing Princeton University Press’s Lockert Library of Poetry in Translation.

As a translator, Cole has brought otherwise neglected poetry to our attention. He won the National Jewish Book Award and the American Publishers Association’s Book of the Year for his dazzling 2007 anthology, The Dream of the Poem: Hebrew Poetry from Muslim and Christian Spain, 950–1492 (Princeton). He edited and translated The Poetry of Kabbalah: Mystical Verse from the Jewish Tradition (Yale, 2012), which Harold Bloom called “the crown of [his] sublime achievement as a poet-translator.”

Cole has also translated contemporary Israeli and Palestinian writers, including Aharon Shabtai (for which he won the PEN Award for Poetry in Translation), Yoel Hoffmann, and Taha Muhammad Ali.

A recipient of the MacArthur Foundation “genius grant” and a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship, Cole has won awards for his poetry and his translations as well as the American Library Association’s Sophie Brody Award for Outstanding Achievement in Jewish Literature for Sacred Trash: The Lost and Found World of the Cairo Geniza (Schocken, 2011), which he wrote with his wife, Adina Hoffman.

During an extensive Zoom conversation, edited here for length and clarity, he spoke with Sources about Jewishness, geography, poetry, teaching, and translation, as well as the nature, in each of these spheres, of “being in relation.”

In your recent books, the bio notes make a point of saying that you “divide your time between Jerusalem and New Haven.” How far does that encapsulate your identity these days, being between America and Israel? Is there something appropriately embodied for a Jewish poet in being in those parallel places—a sense of the geography of translation?

COLE: Well, for one it’s true. I’ve lived and worked and walked and written, gotten depressed, and taken serious kinds of pleasure and responsibility in both those places. But I like that notion: an embodiment of betweenness, which is where so much of what matters to me as a writer and person starts, with a palpable sense of being between, of the richness of that—and also the risk. The receptivity, the vulnerability. Being a Jewish poet has, almost from the start for me, meant charting precisely that “geography of translation,” even if I’m not quite sure what that means. I feel like I feel what it means!

Which is…?

Which is that going elsewhere might just show you who you are and what you might become. That physically, psychologically, imaginatively, you have to work your way into each of the “languages” involved in any broadly translational situation. And then you have to be able to step away from that forcefield of en-counter with the foreign and bring the experience of it across into another field, with other forces—so as to account for the differences and let those differences make a difference.

Is there a Jewish element to that dynamic?

There is for me. The whole question or structural tension of diaspora and so-called homeland has made itself felt in my writing in a subterranean way from the start, not as a process in which diasporas point to their own negation as part of a messianic arrival, but in Bialik’s sense that Judaism has always had certain key polar relationships at its core—Halacha and Aggada, revealment and concealment, maybe also text and commentary, and even agency and marginalization. The history of Jewish civilization has, in some basic way, involved a power and sometimes illumination generated by an alternating current between these poles. Getting rid of one, says Bialik, would prove fatal.

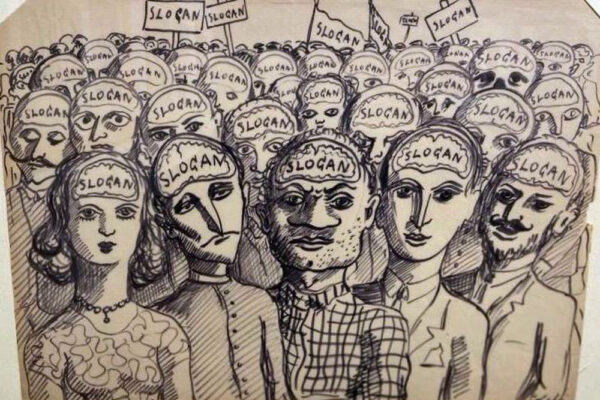

Of course it’s also this oscillation that drives people crazy about the Jews—still! “What exactly are you? You’re not completely this, and not com-pletely that. Do you belong? What do you believe? Can you be trusted?”

The Jewish God might be One, but Jewish learning has two at its heart, as does the art I’m interested in making. It’s worth noting that the words for two and learning and change share a root in Hebrew.

I’ve never realized those words all had roots in common! What does this duality mean for you, in practical terms?

It’s in the weave of every line I write in English and in the translations I make, since the models and even materials of both come from a wide variety of cultures, diasporic cultures and those that emerge, let’s say, from the rocky soil of Israel/Palestine. But it registers on the social surface as well. Years ago, my wife and I were at a conference at an American university with Taha Muhammad Ali, the marvelous Palestinian poet from the Galilee village of Saffuriyya and then Nazareth, whose work I’d translated and about whom Adina wrote a biography. The conference was on something along the lines of “Literature and Mass Violence.” There were people from Rwanda, Northern Ireland, and South Africa. And a contingent of Holocaust Studies specialists, many of whom were Israeli. We’d become very close to Taha over the years, practically like family.

At one point, late in the proceedings, I was up in our hotel room and Adina went down to the lobby to get something, and on the way back she ended up in the elevator with a young Israeli scholar. When the doors shut, the scholar said, “Excuse me, can I ask: Are you and Peter Jewish?” Adina said, in Hebrew, “I don’t mind your asking. Yes, I’m Jewish. My name is Adina. But can I ask you—Why do you want to know?” And the scholar said, “Well, because the way you and Peter seem to be so close to this Arab, I just wondered which side you were on.”

Even there, at a gathering like that, all that richness was being reduced to one thing, or psychologically packaged into mutually exclusive identities.

One of your early, and enduring, interests is the poetry at the intersection of different traditions in medieval Spain: Arabic, Hebrew, Muslim, Jewish, maybe even Christian. How does that fit in?

All these things link up at some level, which is itself an Andalusian notion. Without oversimplifying the politics and histories involved, I was drawn to the Hebrew poetry of Muslim Spain for an evolving variety of literary, personal, and cultural reasons. Initially my interest in Hebrew and its poetry rose up out of a desire to understand what comes before the hyphen when we say that English poetry has historically been a “Judeo-Christian” literature. Two days after I arrived in Jerusalem to begin studying at the Hebrew University ulpan in the summer of 1981, my younger brother was killed in a car accident in Massachusetts. That fueled my study in a way that’s hard to describe—as though I was learning for him, as though I’d acquired a second soul. No more American apologies for my seriousness. On the contrary—that second soul brought with it a kind of doubling down on doubling. An embrace of bothness. An Israeli friend in Jerusalem soon told me about Shmuel HaNagid’s elegies for his brother, Yitzhak, and that became my goal—to be able to read those poems. It was an odd route to the work and what would become my own poetics. And it was certainly a strange way of mourning, through the medieval mask. But that’s how it was, and it changed me.

Jews are a diasporic people. Through the millennia we’ve lived in countless cultures and in countless languages. So, theoretically, we have access to our contributions to that legacy. By that logic, it’s not ridiculous for you to go from your brother’s tragic death and think you’re going to read poems of grief by an 11th-century Iberian Hebrew poet, because those are our poems—our heritage. I’d be interested to hear how you think of yourself in the diasporic tradition of Jewish eclecticism. Do you think of yourself as bringing those things back, renewing those things in an accessible way?

I do think of myself as something of a “renewer” or maybe “re-knower” in that tradition—as translator and as poet—and the Andalusian nexus leads right to it, or up through it. The Hebrew poetry of Muslim Spain is a profoundly expressive body of work and at the same time one that’s intensely involved with its own materiality and sense of occasion, or convention, as well as its hybrid origins. It emerges from a peculiar grafting of Arabic poetics onto the base of a biblical vocabulary, and it blends the mythopoetic universes of biblical and rabbinic Judaism on the one hand, and that of Arabic literary tradition on the other.

Early on I found myself fascinated with these phenomena of derivation, with how it is that this double-derivativeness could result in such a vital body of verse, let alone a medieval one that I felt was somehow speaking for me now. For my deepest grief, for my senses of irony, wit, and the erotic, for my most contemplative self, and for my devotional instinct. All of that came through the musical weave and texture of the poetry, through its rhetorical figures and deep-reaching ornamentation. And it was wholly suspect on the American poetry landscape of the 1970s and early ’80s that I was working my way into—or away from! But I loved what the Iberian Hebrew poetry was showing me, and felt it leading me toward a new and richer way of being in the world, one that radically expanded my sense of what words, arranged in a certain order and with a particular pulse, might do.

There are other influences that came along at key times for me on the diasporic side—the American objectivist poets, and Paul Celan and Edmond Jabès in Paris. And even on the Israeli and Palestinian front, the poets and writers I’ve translated—Aharon Shabtai, Harold Schimmel, Taha Muhammad Ali, and Yoel Hoffmann—were each working out striking displacements and graftings of the foreign and the familiar.

How does your work cross, and re-cross, that line between what is “your poetry”—work that, in a simplistic sense, might carry only your byline—and creatively using the power of existing writing. What you call “derivative”?

All my work feels as though it’s coming out of a translational impulse. Sometimes that’s meant direct translation, but, when it comes down to it, my whole writing life I’ve been playing the diapason or scales of different kinds of transla-tion, whether it’s from inchoate experience to expression as my own poems in my mother tongue, or transformation from another language and period into the English of my own time. Most lately I’ve been interested in collaboration with visual artists and composers, and translation from or into different media, visual or musical. I see them as being all of a piece. They’re analogues of the way we’re always translating experience from one context to another, bringing it to bear on different areas of our lives and the lives of everyone we talk to and work with and meet.

How is that part of being a Jewish writer—if indeed it is?

Ah! That’s where things get slippery, because there are so many different kinds of Jewishness and Jewish writing, and you don’t want to start saying this is a Jewish experience and thatisn’t. That’s a little like trying to pick up spilled mercury with tweezers. But the line of writing that I’ve followed out has a heightened awareness of language at its heart. I don’t consider that an abdication of the poet’s responsibility to account for “personal experience.” On the contrary, language is one of the central things that defines us as human beings. And one of the most powerful aspects of traditional Jewish thinking is its obsession with the operations and permutations of the language that passes through us and in many ways becomes us—as it orders and even creates, and certainly recalibrates, the worlds we know. Continuously.

That counts as personal and emotional in my book. In fact, I’m not sure an-ything is more personal or cuts more deeply than that for me. And I’ve wanted to bear witness to that in my work, in whatever ways I could. From early on I’ve made a commitment to following out lines of affinity and mystery in poetry, and that was one of them—the marvelous materiality of language, and where adequacy meets inadequacy in it. Sometimes when, as the rabbis say, the blessing is beyond the eye, it turns out to be in the ear (Bava Metzia 42a).

So, language. And what else?

A lot else. For one, there’s the whole question of coming “after.” There’s Gene-sis, which isn’t in the beginning at all—both because it’s Greek to most of us and because, in Hebrew, it’s in medias res (Bereisheet). And there’s the Deutero-derivative or belated dimension of so much that became, and continues to become, Judaism, rising up through rabbinic thinking and practice, and of course Kabbalah and its strange deep-readings of surface.

Putting aside the ostensible opposition between what’s “derivative” and what’s “original,” it seems to me that all this this fascination with the dynamics of derivation might lead to another sort of critical human experience: alertness to being “in relation.” Which is itself a kind of discovery, and a basic, difficult, beautiful, at once sensuous and abstract, and always evolving thing.

Speaking of this experience of coming after, of being “derivative,” or “belated”: you knew Harold Bloom very well later in his life. And you wrote strongly about what his still-forming legacy should be in reviewing his posthumous book “Take Arms Against a Sea of Troubles: The Power of the Reader’s Mind over a Universe of Death.” Tell me about your relationship with Bloom. Your writing, like his, is steeped in ideas of derivation or influence. Yet despite your closeness to his thoughts in various ways, you don’t seem particularly influenced by him.

In part that’s because we met only toward the end of his life and pretty late along my trajectory, when I was 50, not long after I’d finished The Dream of the Poem and around the time I published a collection of poetry called Things on Which I’ve Stumbled. But I’d been reading him since the late 1970s, and was always interested in his writings on things Jewish and, especially, Kabbalistic. And that did have a major influence on me—as provocation, or catalyst.

A catalyst, how?

That takes us back to the late 70s. Bloom and two of his closest friends and colleagues at Yale—John Hollander and Geoffrey Hartman (whom Bloom always called the Ayatollah, in part because of his long white beard)—were writing about Jewish-American poetry and what Bloom referred to as “the burden of the past.” Cynthia Ozick was also involved in this at one highly charged polemical moment. Bloom believed that there couldn’t be a Jewish-American poet of real power—as he understood literary power, which is different from how I understand it—because the history of English and American poetry had from the beginning been, as I said earlier, essentially the history of a Christian poetry. Jewish poets, even assimilated Jewish poets, Bloom argued, had an overly ambivalent relationship to these Christian or post-Christian forbears and so were una-ble to identify sufficiently with their precursors in order to rebel against them and, unconsciously, discover their own difference and power. That left the Jewish poet, he believed, in some kind of indeterminate and underdeveloped aesthetic state.

It doesn’t really matter whether I thought that was true or not. I loved and still love the Christian aspect of the older poetry—medieval English is one of my favorite bodies of poetry in the world. But I had a very strong intuition that my own poetry was going to come from another—and Jewish—direction, though not a sentimentally or predictably ethnic one. And it did. And does still.

Thirty and forty years later, after Bloom and I had met, we had long talks about all of this—some of which fed directly and indirectly into a poem of mine called “The Invention of Influence,” about Viktor Tausk, a maverick disciple of Freud. The poem embodies a distinctly non-Bloomian and in some ways rabbinic rather than Romantic understanding of influence, but it’s no less fraught.

Bloom also had an incredible breadth and depth of reading. I was in a class of his in the early ’90s when he was still hale and hearty. Once he told us that Shakespeare’s play Richard II showed a shift in literature toward a certain type of self-consciousness. And he said, “This is the first time in Western literature…” And then he paused and sighed and looked at the ceiling for about twenty seconds and said “…or Eastern literature.” It was as if in that time he had scanned the whole of Eastern literature. For anyone else that would be kind of a laughable performance. With him, you might almost believe he had read all of the literature.

Of course he hadn’t. Though what he had read, and what he retained to the very end, was staggering. His knowledge of the medieval Hebrew poetry and its Arabic precursors was limited, and he didn’t have a granular feeling for how that poetry works. Very few people do—let alone people outside of Hebrew. Ditto with East or Southeast Asian poetics. That wasn’t his wheelhouse, let’s put it that way. But I didn’t care about that. I’m like you in that I wasn’t getting upset about the things he said that didn’t pertain to what I was really interested in. Or, I wasn’t primarily upset about it. Even the whole canonizing business, which always seemed to me more annoying than important. The issue was the light he shed on almost everything he wrote about, or spoke about. He had an extremely rare sort of leverage on the page and in conversation. Love him or hate him, his genius for being alive inlanguage and to it was unmistakable.

In the piece I wrote about Bloom’s book Take Arms, I wanted to get on record some of the ways in which that genius was so much larger than the quarrels over canons and camps and cancelling. That’s the way of narrowness, and the cultural equivalent of a corrosive sort of political intolerance. Yes, he’s responsible for some of that, as I say in the essay. But he loved literature with a kind of informed intensity that I’ve never encountered anywhere else—so I’m willing to put up with, or even welcome, the disagreements. And we had our share of them. It’s important to learn to live with these kinds of contradictions—to let them into the texture of one’s thinking and feeling. This too is an Andalusian lesson, the value of living within these tensions, or letting them live productively in us.

One last question, which seems to float up out of all we’ve been talking about: When I’ve spoken to you over the past few years, it seems that teaching has become increasingly important to you. I wonder whether that’s right, and how and if teaching has an influence on your writing.

It is right. Teaching’s had an important place in the ecosystem of creation that matters to me most: I’m aware that for some writers it takes up too much of the energy and charge that could go into one’s own art. But that sacrifice, as it were, is also part of the ecosystem. At any rate, I love to teach. I love the way it takes you beyond yourself and to others. Teaching is a kind of lab for that same “being in relation” and paying attention that I keep coming back to. You try to be as attentive and responsive as possible—to individuals and to the group. You’re responsible for their progress. You’re also responsible to your subject and its tradition, to your own needs and values as a reader and writer, as an extender or adjuster or dissenter within that tradition. That entails a great deal of effort, and a lot of love—sometimes tough love.

All of which is to say that it both exhausts me and replenishes me. But there’s a kind of slow magic involved. You work hard to introduce new and sometimes surprising things into the collective mix—not to force information down people’s throats and have them spit it back up—but to help them learn how to absorb it responsibly and then respond on their own terms. You can’t control it. You can work hard to set it up and make it possible for something to happen. But you never know what that something will be. And the minute you do know, the minute you think you know what’s going to happen or what should happen in teaching, you stop listening, and you’ve stopped teaching. In that way it’s just like reading and writing and translation. Except that you’re working with invisible ink.