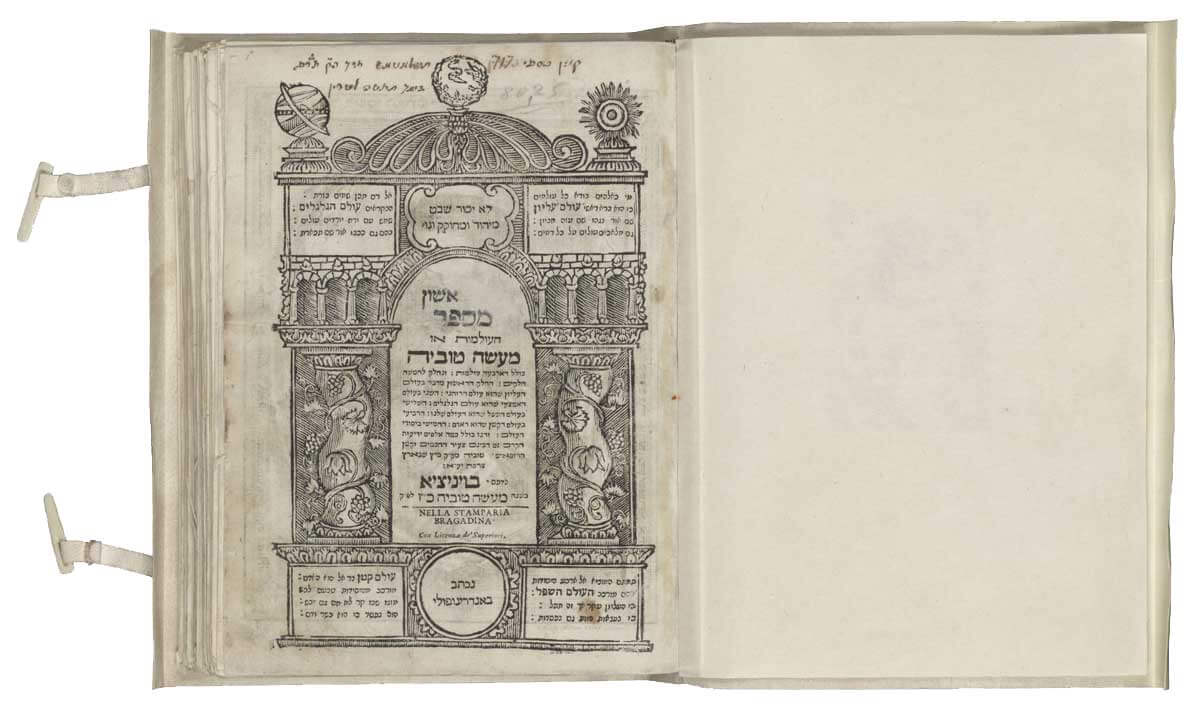

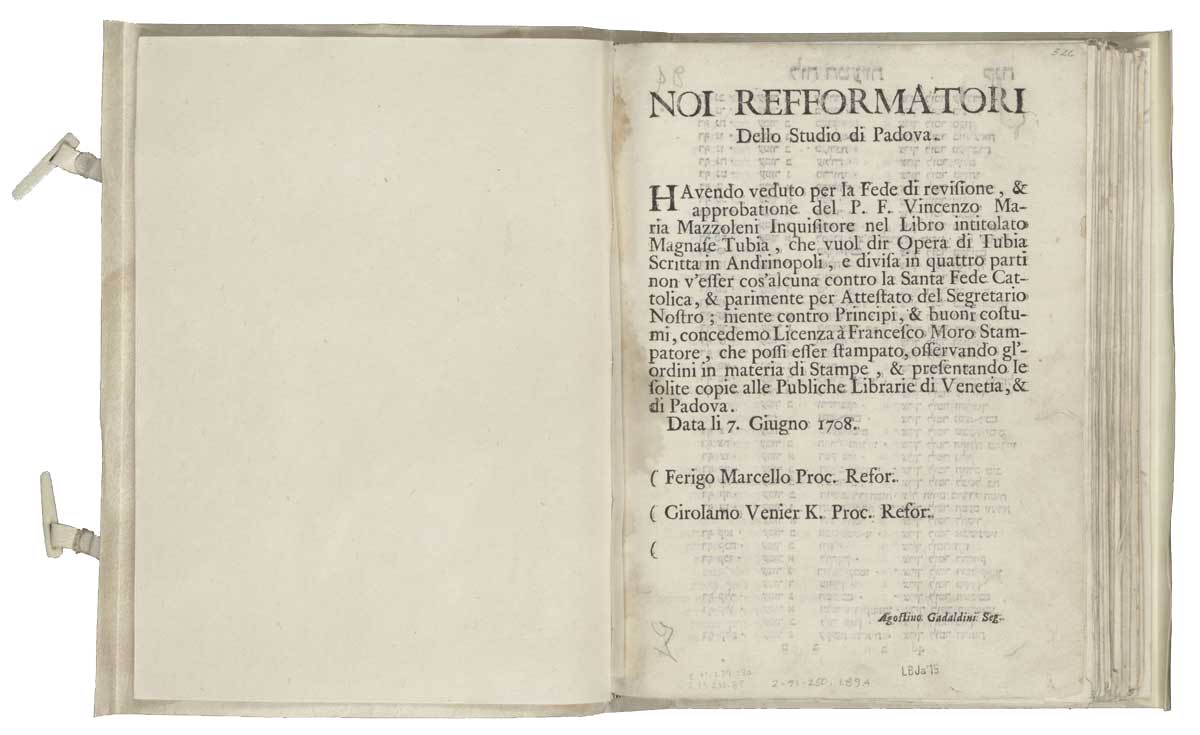

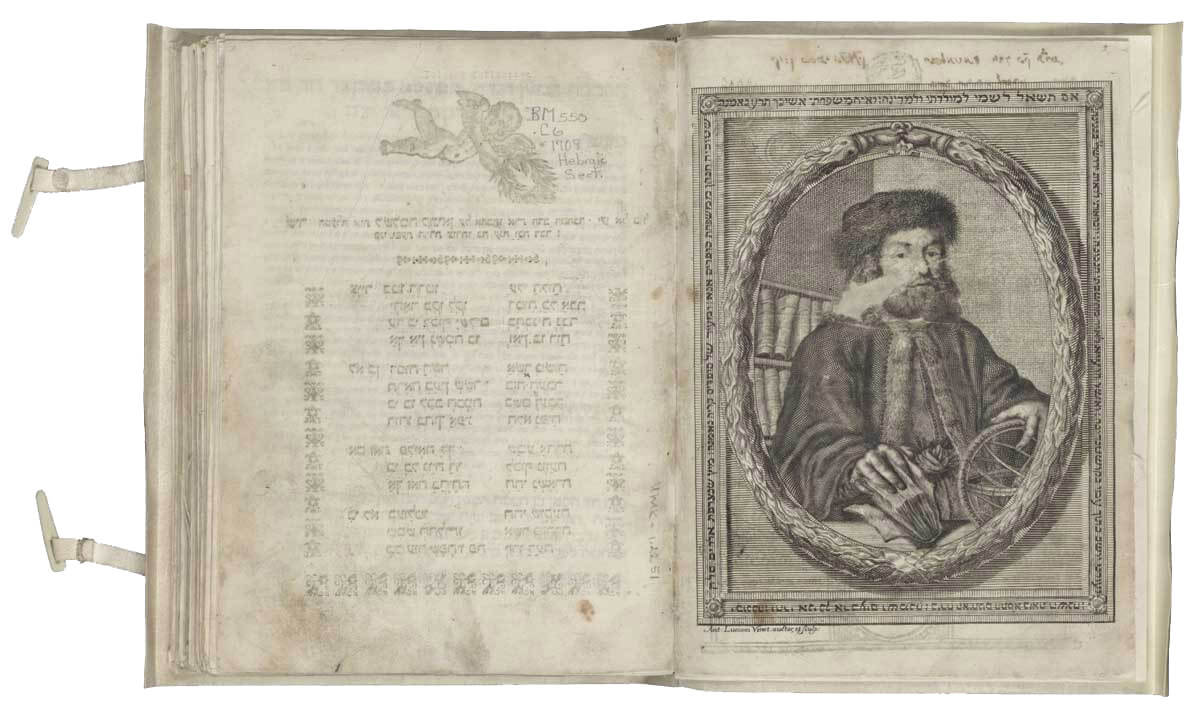

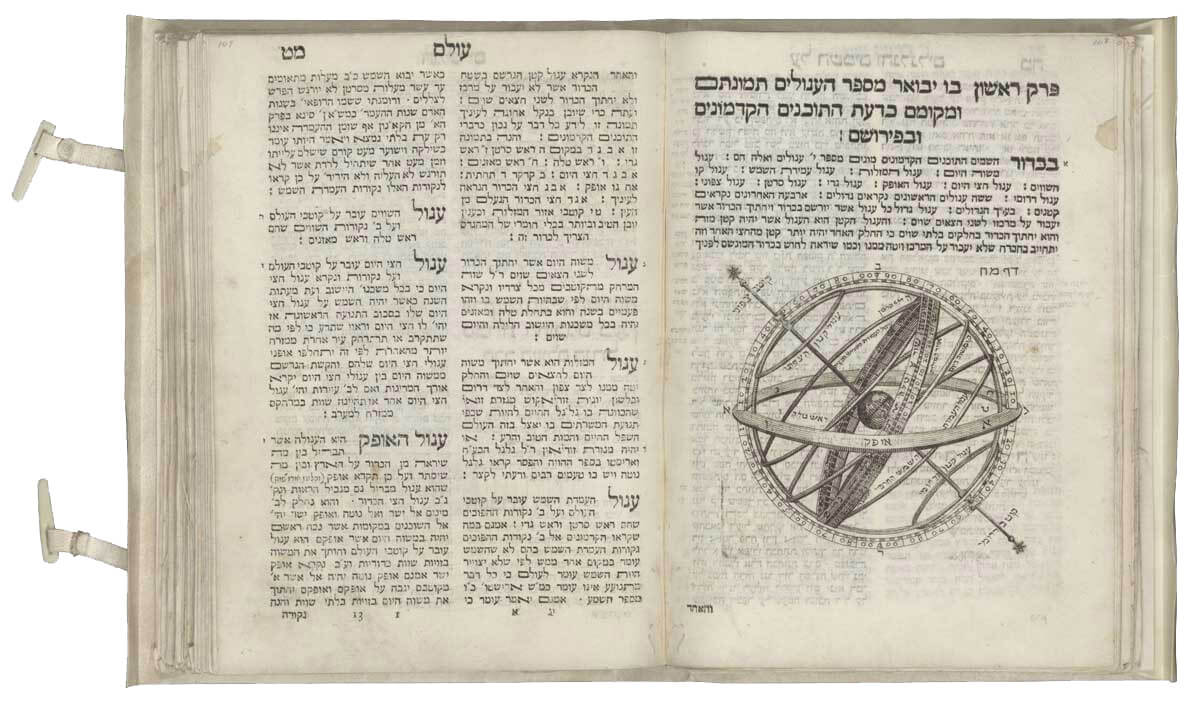

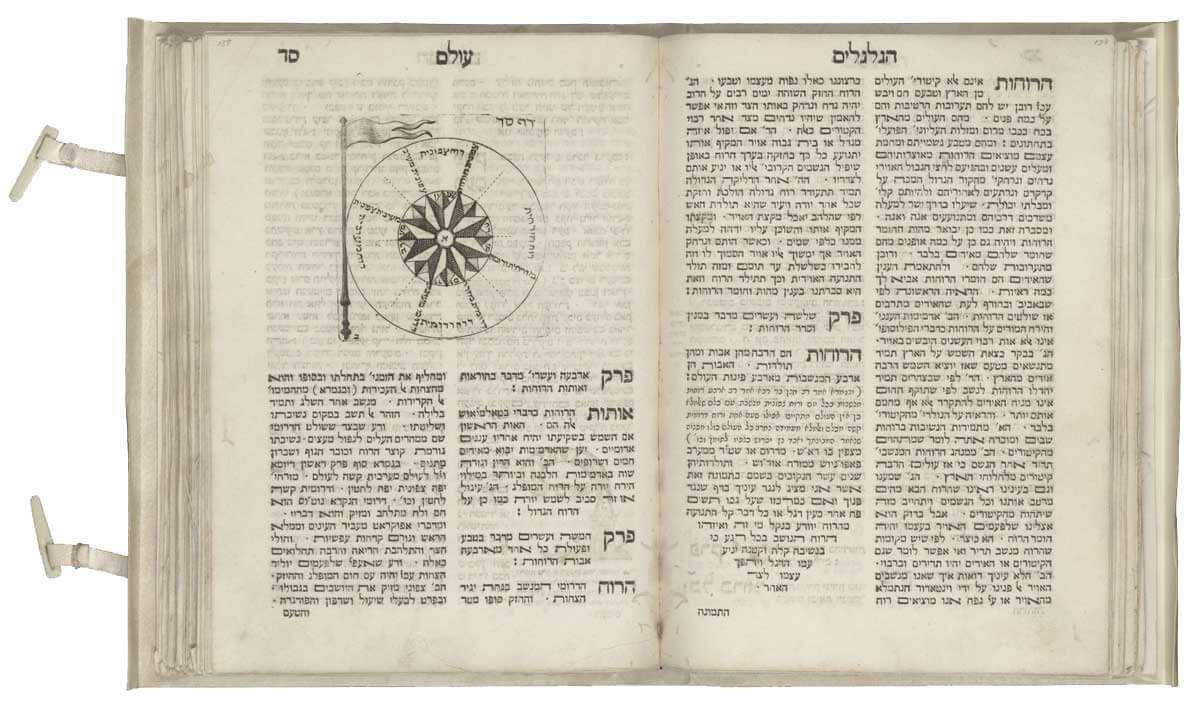

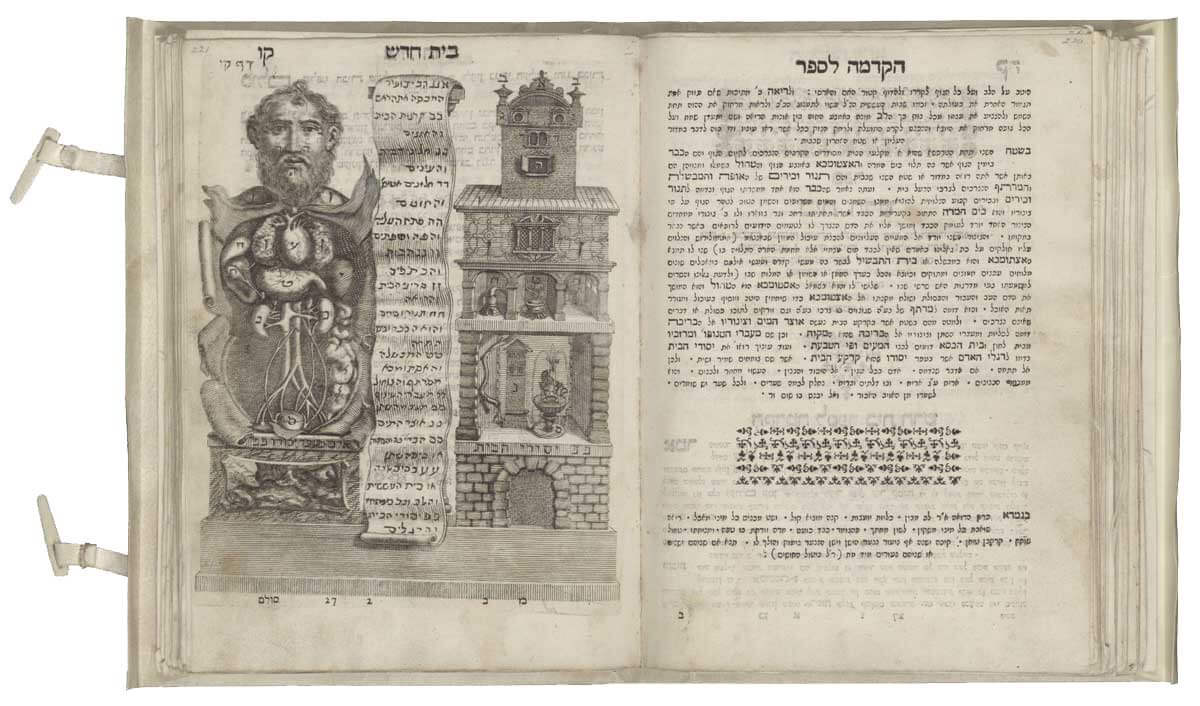

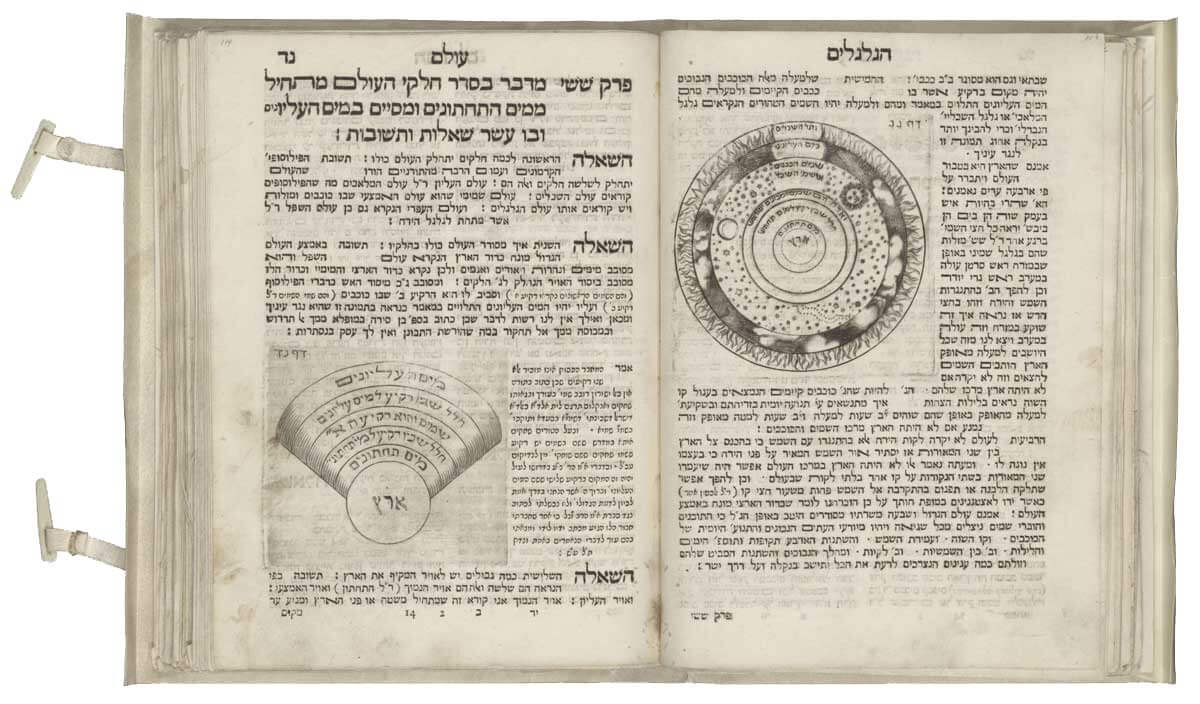

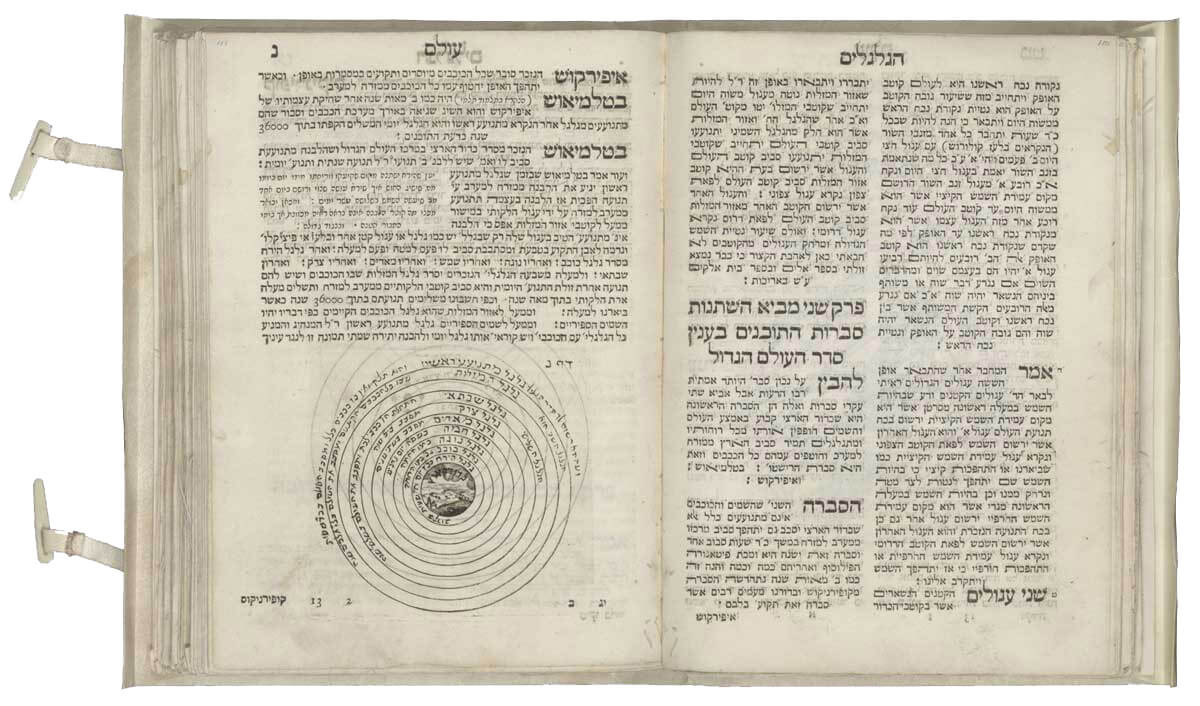

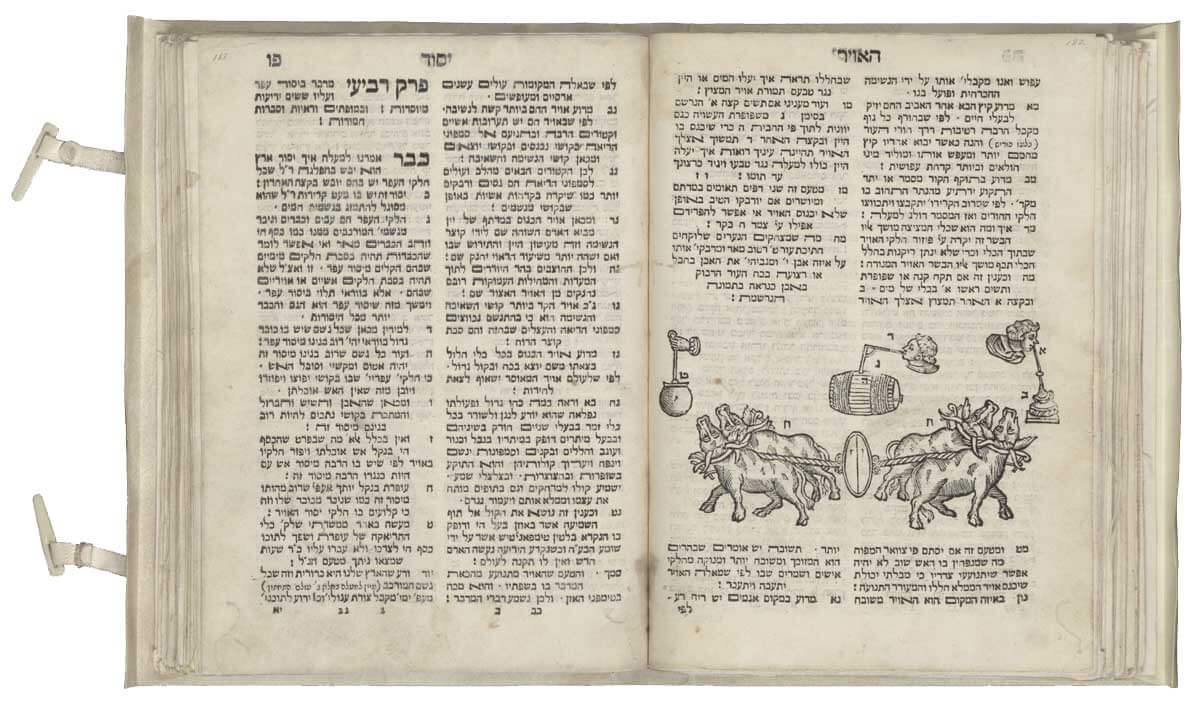

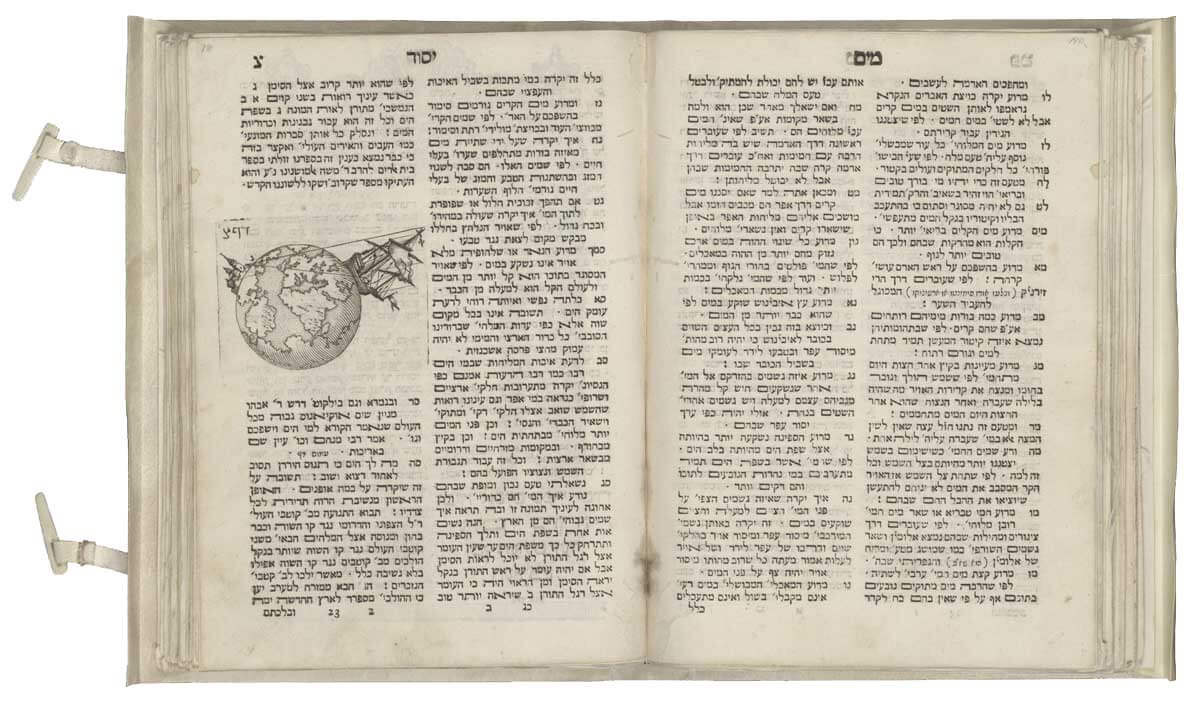

Tobias Cohen, מעשה טוביה (“The Story of Tuviyah”). A Hebrew medical treatise. Venice, 1708. The book is opened to a page in which the human body is depicted as a house; one scholar (Etienne Lepicard, M.D.; Ph.D of the Sackler School of Medicine, Tel-Aviv University) has suggested that it served as a mnemonic device for Jewish students of medicine. Particularly interesting is the image of the stomach, here equated with “a burning cauldron”!

The University of Padua

Since the early 15th century, the Medical School of the University of Padua became one of the first ones to accept Jewish students. Padua maintained a monopoly over medical studies throughout the 17th century when Northern competition and domestic crisis brought it to an end.

Jewish students arrived in Padua from many cities of Europe but the majority of them came from territories controlled by the Venetian Republic. For aspiring Jewish physicians of the time, Padua was the most obvious choice.

The attitude of university and ecclesiastical authorities to Jewish physicians in medieval Europe varied between self-interested acceptance and outright hostility, without consistency on every measure between the two extremes.

Jews had long accessed the medical profession through apprenticeship and were highly respected as doctors even though local licenses were often issued to Jewish physicians to treat only Jewish patients. This condition however was not always observed.

Mostly excluded from universities, which became the norm for the training of physicians, Jews continued to aspire to the practice of medicine. At the same time, Jewish community leaders worried about the risks that accompanied the exposure of their sons to university learning in the Christian world. Rabbi Joseph Solomon Delmedigo (1591–1655), who devoted himself to medicine, writing Refu’ot Te’alah (Healing Medicine), mathematics and astronomy, in his Sefer Elim, warned parents against sending their sons to Padua before “the light of the Torah has shined upon them … in order that they not turn away from it.”

Tobias (Tuviyah) Cohen, a physician whose writings illustrate the exposure to the sciences he encountered at university, counseled that “No one (Jew) in all the lands of Italy, Poland, Germany and France should consider studying medicine without first filling his belly with the written and oral Torah and other subjects.”

Studying in Padua did give Jewish students access to the local Jewish communities, both in Padua and in Venice, where there were opportunities for Jewish students to familiarize themselves with the language and subjects required for the medical course, and which were not available to them in their own communities. Solomon Conegliano’s private tuition was praised by Tobias Cohen in his Ma’asei Tuviya, describing Conegliano as one of the greatest physicians and philosophers of his time.

Tobias Cohen is probably one of the best-known medical graduates of the Padua Medical School, through his influential and comprehensive medical and scientific work Ma’asei Tuviya published in Venice in 1707, and his professional journey illustrates many of the problems faced by Jewish medical students and physicians of his times.

He was born in Metz in 1652 where his family had fled from Poland in 1648 during the Khmelnytsky persecutions. His father and grandfather were both rabbis and physicians, and Tobias returned to Poland and studied at yeshiva in Krakow before entering the University of Frankfurt in 1678 with a Jewish colleague, Gabriel Felix of Brody. Tobias and Gabriel made the choice to go to Padua rather than Leiden. After graduating in Padua, he moved to the Ottoman Empire where he lead a successful career. His medical teachings were quite influential among his Ottoman colleagues. Tobias Cohen ended his life in Jerusalem in 1729.

Tobias Cohn, The Story of Tuviyah, Venice 1708, Library of Congress

Reference: Kenneth Collins, Jewish Medical Students and Graduates at the Universities of Padua and Leiden: 1617–1740, 2013