When Elsa Morante published La Storia in 1974, it hit Italy like a storm, quickly becoming the most talked about book of the year.

In the first year it sold, in Italy alone, a record 800,000 copies (at a time when a successful novel rarely sold more than 100,000 copies).

The book literally spellbound its readers.

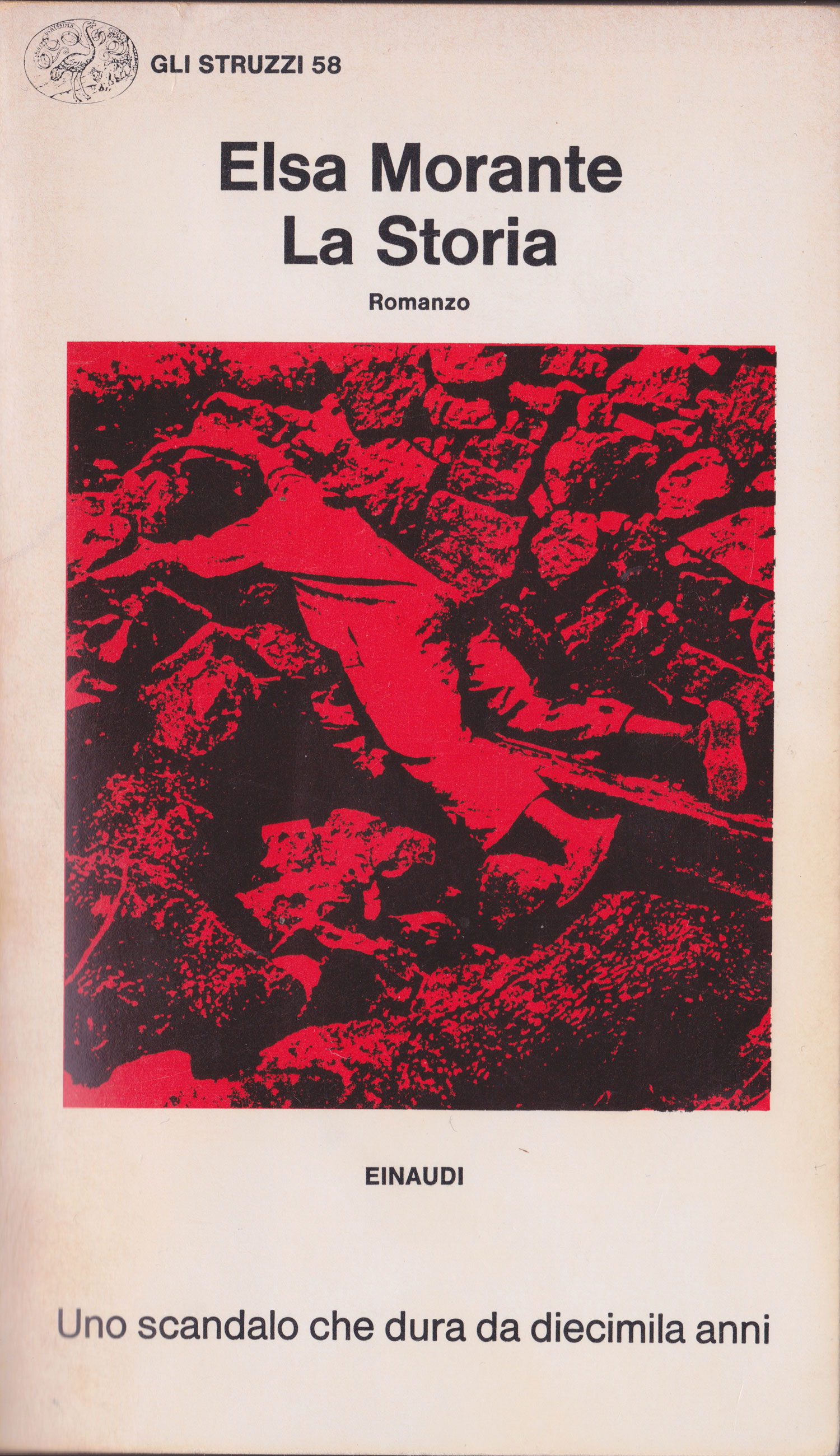

Morante insisted that her publisher, Einaudi skip the hardcover version and go directly to paperback. She also decided to keep the price low, at 2,000 lire (then the equivalent of about $5), giving up significant royalties. For the cover, she insisted on a detail from an iconic Robert Capa image of a dead antifascist during the Spanish Civil War. Under the photo, she placed the phrase: “Uno scandalo che dura da diecimila anni.”

“A scandal that has lasted for ten thousand years”

To precisely which scandal is she referring to?

When the novel was published in English in 1977, Morante was so upset that the American edition lacked a warning paragraph, that she tried to rectify it by consenting to a simultaneous edition for the Franklyn Library First Edition Society in which she wrote a long message to the members of FFE Society.

“In the original Italian Edition, this novel, under its title History, bears the following subtitle: A scandal that has lasted for ten thousand years. These words already define the theme which the novel then develops and orchestrates. […] Glancing through any summary of World History, one discovers immediately that the vast course of human events, despite its upheaval and unevenness, displays a landscape of obsessive monotony. Historiography, no matter how much it explores, finds everywhere the same, unceasing scandal. Remote or near, every human society is discovered as a tormented field, where a squad performs violence and a throng suffers it […]

In Italy, the novel turned out to be a cultural and literary scandal, quickly dividing readers into those who hailed it as a masterpiece and those who objected to it on ideological grounds.

Before La Storia, Morante had not published a novel since L’Isola di Arturo (Arturo’s Island) in 1957. While working on La Storia, she did not give details to her publishers, husband, friends or colleagues except to say, “I am writing a novel for the illiterate.” The book in fact bears as an opening quotation a line from the Peruvian poet Cesar Vallejo, “Por el analfabeto a quien escribo“ (“To the illiterate for whom I write”).

A second quotation from the Gospel of Luke, reads “… thou hast hid these things from the wise and prudent, and hast revealed them unto babes… for so it seemed good in thy sight.” This verse introduces another theme of the novel: the wisdom, purity and redemptive power of children.

Paul Hoffman, writing from Rome for the New York Times, reported:

“For the first time since anyone can remember, people in railroads compartments and espresso bars discuss a book—the Morante novel— rather than the soccer championship or the latest scandal. The critics write endlessly about the meaning of La Storia and the reasons for the exceptional stir it is causing”.

No post-war Italian literary work had ever been as divisive. The only precedent on a smaller scale and involving exclusively a literary debate was Tomasi Di Lampedusa’s posthumous The Leopard in 1958.

Foreign publishers quickly began to buy the rights to translations. A Spanish publisher had advanced $15,000 before Franco’s regime banned the book. In English, the rights were acquired by Alfred Knopf, who published the novel in 1977, in a translation by William Weaver, who at the time lived in Rome and was a close friend of Morante. Unfortunately, the translation was labored and almost broke their friendship.

Even the title was a challenge: La Storia in Italian means both History and the story, and the ambiguity between these two meanings is an essential element of the work. In English it appeared as History, A Novel, in 1977 as an Alfred Knopf hardcover, and was most recently re-issued in paperback by Steerforth Press in 2000.

By 1974, Italy, torn by ideological wars that followed the uprisings of 1968, was entering a time plagued by terrorism on the left and right, “gli anni di piombo.” The critical debate over History, only thinly veiled the unsophisticated question that was being asked: Is Morante’s novel left or right wing? Is it a new popular and proletarian form of narration or a reactionary bourgeois novel? In truth, no one knew where to place this novel with its anarchist non-violent thrust and its non-Marxist reading of history. As the critic Cesare Garboli recalled:

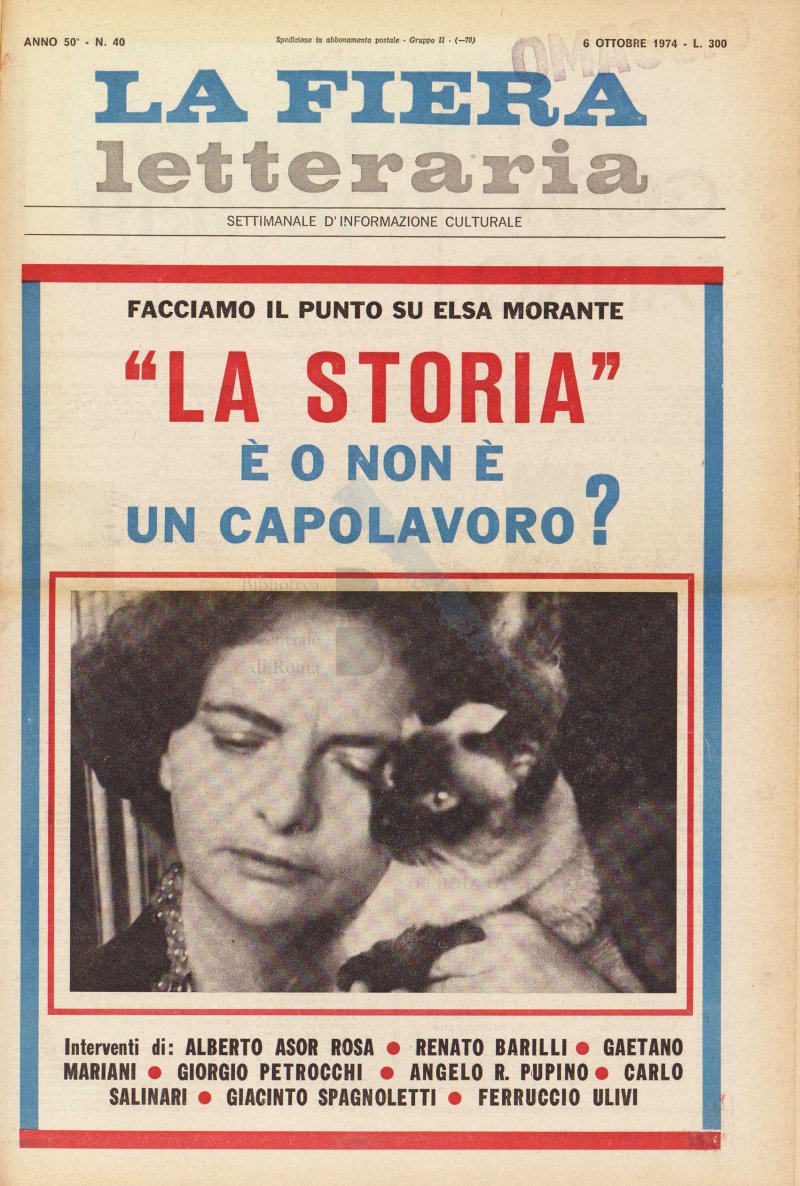

“The controversy spread to the press. The far left daily paper Il Manifesto, was bitterly divided. The weekly L’Espresso organized pro and con polls among its critics. The weekly La Fiera Letteraria titled “Is it or isn’t it a masterpiece?”

Among the many prominent Italian writers who at the time took a position against La Storia, Nanni Balestrini, an experimental writer associated with the avant-garde movements Novissimi and Gruppo 63, saw the novel as a reactionary sanctification of poverty and suffering. Pier Paolo Pasolini, who from the mid-1950’s had been a close friend of Morante and shared her desire to uncover the multilayered deception behind the promise of progress in the newly affluent Italian society, famously trashed La Storia. Though he much admired the first 150 pages, he felt the structure did not hold:

“The whole novel is configured as a comparison between life and History: between one chapter and another of the novel (conceived as annals) there are brief inserts that summarize the objective historical events – from 1941 to 1967 written as a history manual. In the first part of the novel, this gimmick is extraordinary and I would say, “structural”, to the novel. […] Then the”effect” of the confrontation of life with history suddenly becomes lost and expires.”

After penning a negative review, Umberto Eco conceded:

“Perhaps one day we will realize that History was only seemingly a novel aimed at a general public, while in reality, it is a very cultured, very meta-literary one, who knows…”

La Storia is a multilayered novel of gargantuan ambition. One aspect, it seems to me, that has escaped critical attention is the centrality of the Race Laws of 1938. More specifically, the way the Laws impacted the children of mixed marriages, and in particular, those who — removed from direct contact with the Jewish Community — concealed their dark secret, without the relative comfort of sharing their fears and hardships with others. The female protagonist of the novel, as with the author herself, belongs to this category.

Morante describes the devastating sweep of history from the point of view of people whose existence has been reduced to a struggle for food and shelter. At the bottom of the diverse group we find a middle age school teacher, a single mother, a half-Jew, facing the brutality of the Race Laws with no recourse at all.