At home, alone, Ida plunged into a complicated calculation. For herself, really, the solution was simple: born of an Aryan father and a mother whose family had been Jewish for many generations, she had only six points out of twelve, and the result was therefore negative.

But her main concern, namely Nino, proved more abstruse, and here the sum, as she computed it again and again, became muddled in her brain.

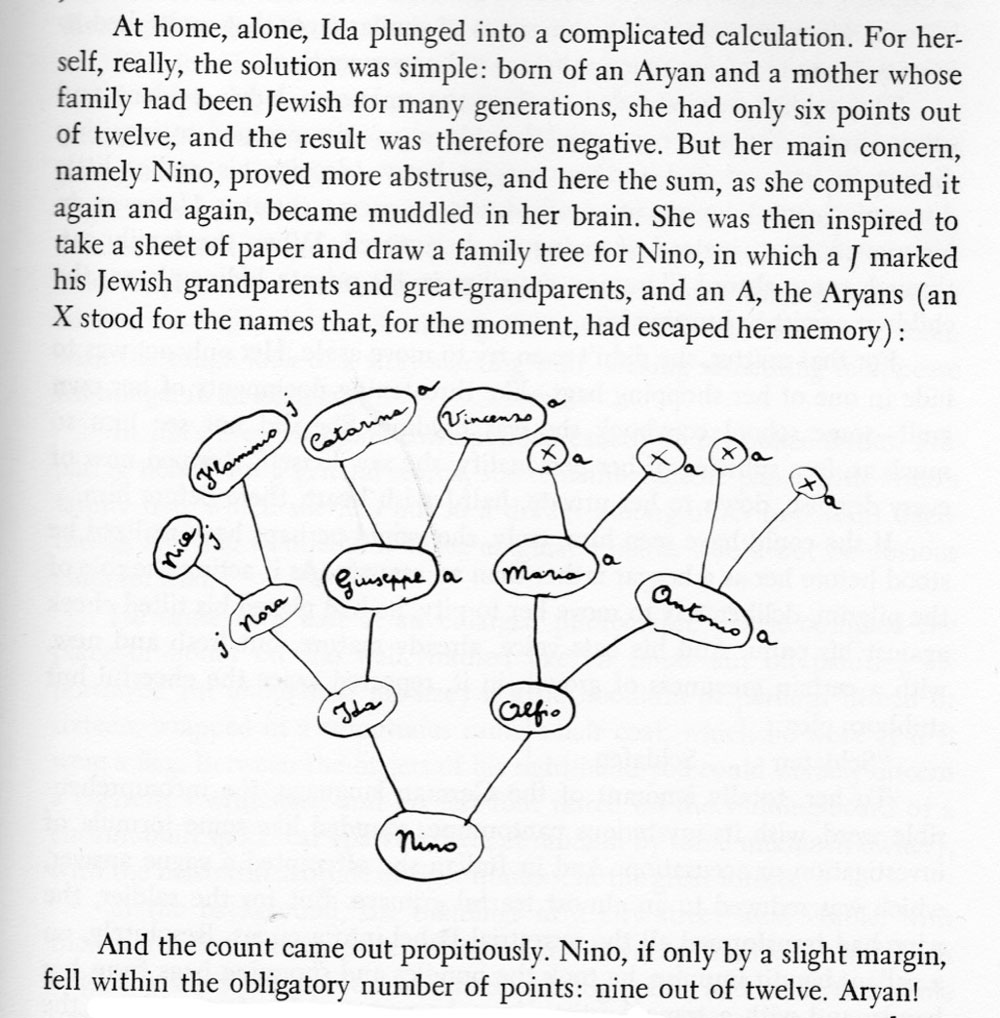

She was then inspired to take a sheet of paper and draw a family tree for Nino, in which a J marked his Jewish grandparents and great-grandparents, and an A, The Aryans. An X stood for the names that, for the moment, had escaped her memory. The count came out propitiously:

Nino, if only by a slight margin, fell within the obligatory number of points: nine out of twelve. Aryan!

The war years, and the immediate aftermath in Rome, are both the backdrop and foreground of the unraveling of the lives of Ida Ramundo and her sons. Rome, the imperial capital, the city of the Pope, a city first bombarded by the Allies then invaded by the Nazis, and above all, Rome as the symbolic caput mundi of a world transfigured by war.

Yet perhaps, as never before or after in a novel, Rome is here seen as the city where the Race Laws were conceived and promulgated and where the single largest roundup of Jews in Italy took place.

Morante’s story focuses specifically on the “casualties of history” individuals who, rather than participate, are run over by historical events: the dispossessed, wartime evacuees, veterans, the poor, women and children, and the victims of the Race Laws, the Jews.

Morante explains Ida’s difficulties in making sense of the Race Laws. Despite her exclusion from the decrees’ reach, they marked her forever as a half-Jew.

Nora, with her death had eluded by a few months the Italian racial decrees, which now stigmatized her irremediably as a Jew. However, her foresight, which thirty-five years earlier had led her to have Iduzza baptized a Catholic, now saved the latter from loosing her post as a schoolteacher and from other punitive provisions, according to paragraph d) of Art.8: Anyone born of parents of Italian nationality, of whom only one Jewish, shall not be considered of the Jewish race if, on the date of 1 October 1938-XVI, he was of a religion other than Jewish.

Within the wide sweep of events narrated, and the multitude of characters, sub plots and digressions, in my reading, the devastating impact and ultimate barbarism of the Race Laws are prominently at the core of the narration. Ida’s encounter with the young German soldier and her misreading of his intentions point to her terror, as a half-Jew, living under the Race Laws: “… seeing him confront her, she stared at him with an absolutely inhuman gaze, as if confronted by the true and recognizable face of horror.”

As a person living in disguise, she felt discovered: “He must be an agent of the Racial Committee […] come to identify her.” She instinctively hid the evidence of her crime —continuing to teach elementary school despite being half-Jewish.

“Her only act was to hide in one of her shopping bags — like threatening documents of her own guilt— some school copybook she was holding.”

By 1974, separate and often diverging historical narratives had been elaborated to account for Jews, fascist and anti-fascist, partisans, anarchists, communist, veterans from Mussolini’s disastrous wars, cynics and opportunists: this novel intertwines all these different narratives exposing them as simultaneous sides of a common man-made tragedy.

The anti-Semitic propaganda leading up to the Racial Laws affects Nora, Ida’s Jewish mother, deeply. Despite having married a Catholic and neither practicing her Judaism, nor having any contact with the Jewish Community, Nora feels deep anxiety, vulnerability and a lack of protection. All of this is passed down to Ida, who is one step further removed from her Jewish origins. Indeed, Ida did not participate when Mussolini forced a census on Italian Jews before the Race Laws.

And when the Laws were implemented, though she only obliquely understood in what ways the legislation was aimed at her, it terrorized her. Ida’s existence is so marginal that even the usually efficient fascist authorities don’t seem to notice her at all. Yet this in no way spares her constant anxiety. In her naive mis-reading of the Race Laws she believes her destiny hinges on the spelling of her mother’s maiden name, or rather on the presence or absence of an accent: Almagìa, would give away her Jewish origin, while Almagia, could pass for an Aryan name. The Race Laws are a looming presence throughout the narrative. At different times they are explicitly referred to, alluded to, or just there. At no time can they be ignored, not even when the plot moves elsewhere and they temporarily recede into the background.

Ida’s story proceeds chronologically from 1941 to 1947. Looking closely at how the Race Laws of 1938 are presented in the story alerts us to how Morante’s narration moves back and forth in time.

The description of the fatal street encounter between Ida and Gunter occurs in the opening chapter, which ends with Ida seeing in the German soldier “the true and recognizable face of horror,” as described above. The scene is interrupted, or rather, its unraveling is postponed, for thirty-seven pages until Chapter 4.

In the interim, we learn about Ida’s family and particularly about her mother, Nora’s two secrets: being Jewish and suffering from epilepsy. Chapter 3 begins with the texts of the crucial articles (1-8-9 and 19) of the Race Laws, as they appeared in the newspapers and were read by her mother. In that same chapter, we are made aware of Ida’s rare and marginal status as an “underground Jew,” not a part of the Roman Community still living in the former Ghetto, who inescapably felt the brunt of the racist legislation.

No other novel captures in quite the same way the terror and disbelief of not only Jews, but those of Jewish descent, half-Jews, lapsed Jews, who were suddenly degraded to second-class citizens. In fact, an accurate subtitle could have been: “Daily Life Under the Race Laws.” In contrast to the Roman Jews who lived around the former ghetto and had a strong sense of community, Ida embodies those who suffered the Race Laws without the possibility to connect with others who shared the same plight.

In time, Ida comes into meaningful if minimal contact with the Jews in the former ghetto in three striking scenes. First, she goes to the ghetto and finds a midwife who helps deliver her unexpected son. Second, on October 17, 1943, after the roundup, she accidentally stumbles across the Roman Jews locked in sealed cattle cars, waiting for their departure from Rome’s Tiburtina Station. And a third, when in an hunger-induced daze, Ida wanders into the deserted Ghetto, long after the deportation of October 16, 1943.

Recovering herself with a jolt, she was embarrassed to find her lips drooping and saliva running down her chin. She stood up, unresolved, and having walked only halfway across the Garibaldi bridge, she realized she was heading for the Ghetto.

She recognized the call that was tempting her there and that came to her this time like a low and somnolent dirge, still loud enough to engulf all exterior sounds. Its irresistible rhythms resembled those with which mothers lull their babies, or tribes summon their members together for the night. Nobody has taught them, they are written already in the seed of all the living, subject to death.

Ida knew that the little quarter, for months now, had been once more cleared of all its population: the last evaders from the previous October, having stealthily returned to their narrow rooms, had been rooted out again in February, one after the other, by the Fascist police in the service of the Gestapo; and even refugees and vagabonds avoided the area… However, in her head today, this news was lost amid reminiscences and older habits.

In some confused way, she still expected to encounter there the usual gang of little families with curly hair and black eyes, in the street, at the doorways and windows. […] Ida dragged herself through it as if in an enormous maze without beginning or end; and no matter how much she roamed about, she always found herself at the same point. She vaguely realized she had come here to deliver something to somebody; indeed, she knew this somebody’s last name; EFRATI, which she kept repeating to herself in a low voice so she wouldn’t forget it. And she looked for someone she could ask for directions.

But there was nobody, not even a passerby. No voice was heard. To Ida’s ears, the perpetual roll of the cannon in the distance was confused with the echo of her own solitary footsteps. Here, separated from the traffic along the Tiber, the silence of these sunny little alleys isolated the senses like a narcotic injection, excluding all surrounding, populated territory.

Through the walls of the houses, you could strangely feel the resonance of their inner voids. And she kept on murmuring EFRATI, EFRATI, entrusting her self to this uncertain thread to keep from being completely lost. There she was again in the broader space with the fountain. The fountain was dry. Dead plants trailed from the narrow street’s little loggias and decrepit balconies. At the hovels’ window there was no longer the usual array of underpants, diapers, and other rags strung out to dry; at either side, from the outside hooks, the little broken lines were still hanging. And some windows had shattered panes.

Through the grille of a street level room, formerly a shop, you could glimpse the damp, dark interior, stripped of the counter and the merchandise, and invaded by cobwebs. Some doors seemed barred, but others, bashed in during the looting, were ajar or half-open. Ida pushed at an unhinged door, with only one leaf, then closed it behind her back.

The entrance hall, the size of a closet, was almost in darkness, and it was cold there. but the little stone stairway, all worn and slippery, received light from a window at about the level of the third floor. On the second landing there were two closed doors; but one of the two had no name. The other had, written in pen, on a little glued card: Astrologo Family, and on the wall, above the bell, two more names, in pencil: Sara Di Cave, Sonnino Family. Along the wall of the stairs, peeling and covered with stains, you could read various writings, most of them obviously by childish hands: Arnaldo loves Sara—Ferruccio is handsome (and below, added by another young hand: he’s a shit) —Colomba loves L —Roma’s the winner.

Frowning, Ida examined all the writings, in an effort to decipher her own confused reasoning in them. The house had two upper stories in all, but the stairways seemed very long to her.

Finally, at the next landing, she discovered what she was looking for. Actually, the number of people named EFRATI in the Rome Ghetto was beyond counting. There was no stairway, you might say, where one wasn’t to be found. Here there were three doors. One, without a name and off its hinges, opened into a windowless cubbyhole, with the springs of a bed on the floor and a basin, both battered. The other two doors were closed. On one, there was a little plate with the name: Di Cave, and above it, written on the wood, also the names: Pavoncello, Calo’. And on the second, a broad piece of paper was glued, which said: Sonnino, EFRATI, Della Seta.

In her weariness, Ida couldn’t resist the temptation to sit down on those iron springs. From the broken window over the stairs came a swallow’s shriek and she was amazed by it. Heedless of air raids and explosions, that little creature had flown across the sky — its fragile body unerringly oriented—as on a domestic path. While she, a woman, and over forty years old, found herself lost.