While references to world events and the unfolding of World War II are confined to the nine prefaces, the novel focuses on daily life in Rome between 1941 and 1947. Yet, as with everything in this novel, the question of chronology is a complicated one.

In my reading, Morante’s central concerns are centered on the Race Laws of 1938 and their effects specifically on the children of mixed marriages, thus the novel includes events dating well before the starting point of 1941.

The entire narrative construction consists of Morante’s creation of fictional antecedents to a scene reported by local newspapers in Rome in June 1947: the discovery of a dead six-year-old child with his mother gone insane, in an apartment guarded by a ferocious she-dog. From this scant report, Morante’s imagination created a whole novel around what may have preceded and caused this grim scene.

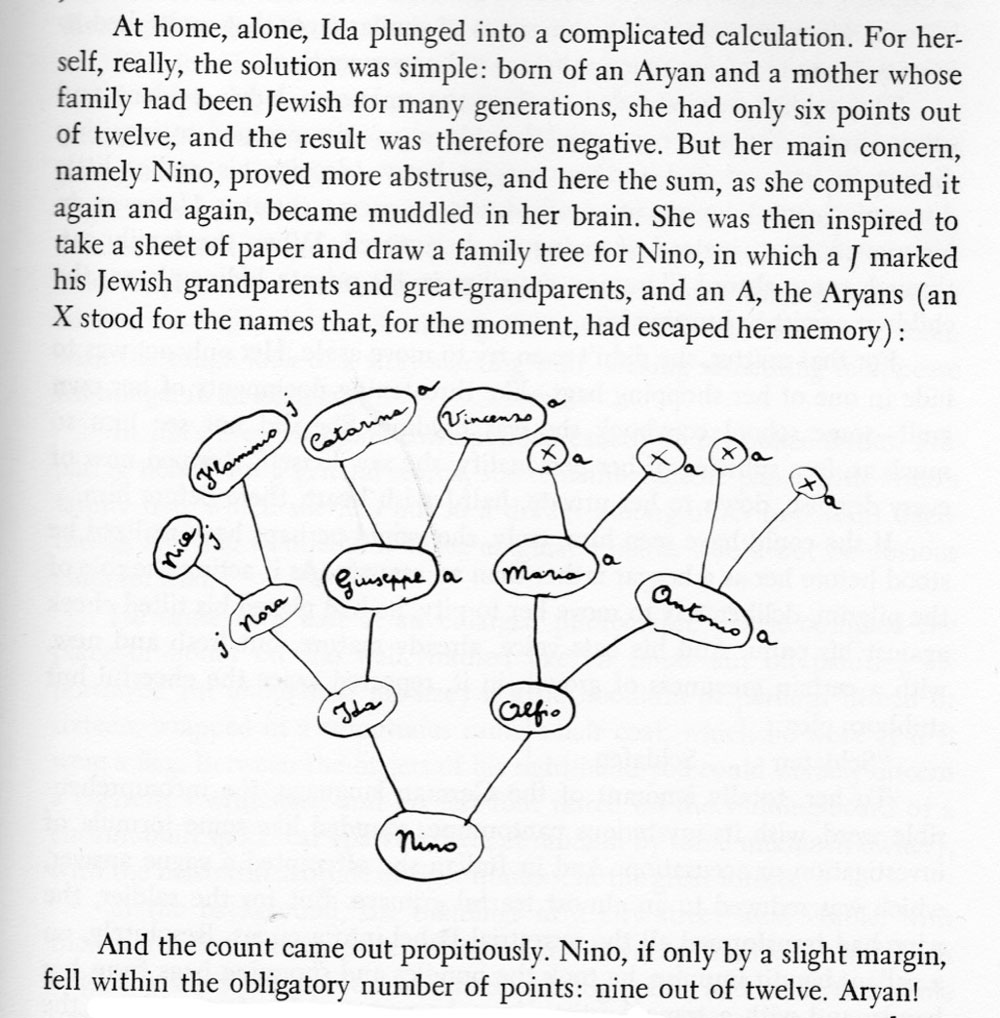

For this reason, the apparently random beginning of the narration in 1941, allows the child to die at six, in 1947. The technique chosen by Morante is that of repeated, often very long, flashbacks. The opening scene in Chapter 1, finds Ida in January 1941, teaching elementary school while hiding her status as a half-Jew under the Racial Law. The entire second chapter takes us back to Ida’s childhood and her family of origin, where we learn she is the product of a mixed marriage. Her mother is Jewish and her father Catholic. We also learn that her mother, and Ida after her, suffered from misdiagnosed epilepsy. Chapter 3 begins with the texts of crucial articles from the Race Laws. Only in Chapter 4, does the narration return to 1941, where it had begun.

Ida Ramundo’s tale is intertwined with major events in wartime Rome:

—The Allies’ bombing of San Lorenzo, on June 19th, 1943.

—An example of partisan activities in the countryside around the Castelli Romani.

—The nine months of German Occupation from September 8, 1943, to June 4th, 1944.

—The roundup of the Jews on October 16th, 1943.

—The deportation by train of the Roman Jews from Stazione Tiburtina on October 19, 1943, headed for Auschwitz.

Morante diverges in many ways from a merely historical account of Rome during those years. For example, she limits the dramatic nine months of the German occupation occupy a few terse pages. According to estimates by the historian Cesare De Simone, during that period 400,000 people were living in hiding in Rome: Jews, draft dodgers, deserters, anti-fascists, and partisans. Yet in the passages about life under Nazi rule, Morante describes a ghost town in which Ida, in the hallucinatory grips of hunger, and her son Useppe, seem utterly alone in a city with a undetermined mass of suffering people.

Enlarge

There is no doubt that for La Storia, written between 1971-74, Elsa Morante conducted very accurate and detailed research. Regarding the roundup and deportation of the Jews, Giacomo Debenedetti is a key a reference particularly in light of Morante’s long friendship with the Italian literary critic. In an author’s note to the American edition, she writes:

As far as the bibliography of the Second World War is concerned, since it is obviously vast, I can only refer readers to some of the many accounts everywhere available on the subject.

Here I must limit myself to mentioning — also by way of thanks — the following authors who, with their documentation and testimony, have given me some (real) suggestions for some (invented) individual episodes in the novel: Giacomo Debenedetti (16 ottobre 1943, Il Saggiatore, Milan 1959); Robert Katz (Black Sabbath, Macmillan, Toronto, 1969); Pino Levi Cavaglion (Guerriglia nei Castelli Romani, Einaudi, Rome, 1945); Bruno Piazza (Perchè gli altri dimenticano, Feltrinelli, Milano, 1956); Nuto Revelli (La strada del Davai, Einaudi, Turin, 1966, and L’Ultimo fronte, Einaudi, Turin, 1971).