I.Italy: The Life of a “Foreign Italian”

Leo Yeni, an Artist’s Paper Life, presented by NYU Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò in collaboration with Centro Primo Levi showcases the life and struggles of a man through his art. To some, the show, curated by Cynthia Madansky, is an interesting look into the mind of the artist, who like many other Italian jews was abandoned by his country, to others such as Lillian Spiegel, it’s one more step towards giving Leo what he never managed to obtain during his lifetime, Italian citizenship.

In 2019, Lillian Spiegel walked into New York University’s Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò with a project in mind. She wanted to organize an exhibition of the works of Leo Yeni, featuring drawings and sketches, mostly made during the artist’s permanence in a Swiss internment camp, as well as paintings, family photographs and official papers.

Leo Yeni was born in Italy in 1920 from a Greek father, Isac Yeni, who moved to Italy in 1912 following the eruption of the Italo-Turkish war. There, Isac became an accountant for the Italian Commercial Bank and married the Livornese Pia Della Torre, Leo’s mother. At the time, Italian law dictated that if a woman married a foreigner she would adopt her husband’s citizenship and lose the Italian one and that’s what happened to Pia.

So, although they lived in Italy, all members of the Yeni family were effectively foreigners in the country, a fact that didn’t affect their daily life much until Mussolini took power and racial laws were instituted. After losing their rights and means of livelyhood, as foreign Jews, the Yenis were expelled from the country. They were given until March 12, 1939 to leave, but having nowhere to go, they remained, moving to the countryside, where they stayed until 1944.

Leo eventually managed to cross over into neutral Switzerland, where his father’s cousin, Isac de Abravanel, could host him. Crossing the border had become extremely dangerous, particularly after the police of the Italian Social Republic issued the arrest warrant against all Jews present on Italian territory in November 1943. It was constantly patrolled by Nazi and Fascist soldiers. Many who tried to cross were either rejected by the Swiss or sold by the guides they had hired. In his diary, Leo describes the preparation and farewells in great detail.

His parents, who were then 63 and 75 years-old, remained behind and, according to official documents, they were arrested a few weeks later, detained in Milan and then deported to Auschwitz where they were both killed.

Leo’s journal entries – shown in the exhibition – reveal that his journey to Lugano was tumultuous to say the least, he got lost on the snow-clad mountains shortly after crossing the border, accidentally found himself back on the Italian side and deemed it safer to return home, where he arrived just after his parents had been arrested.

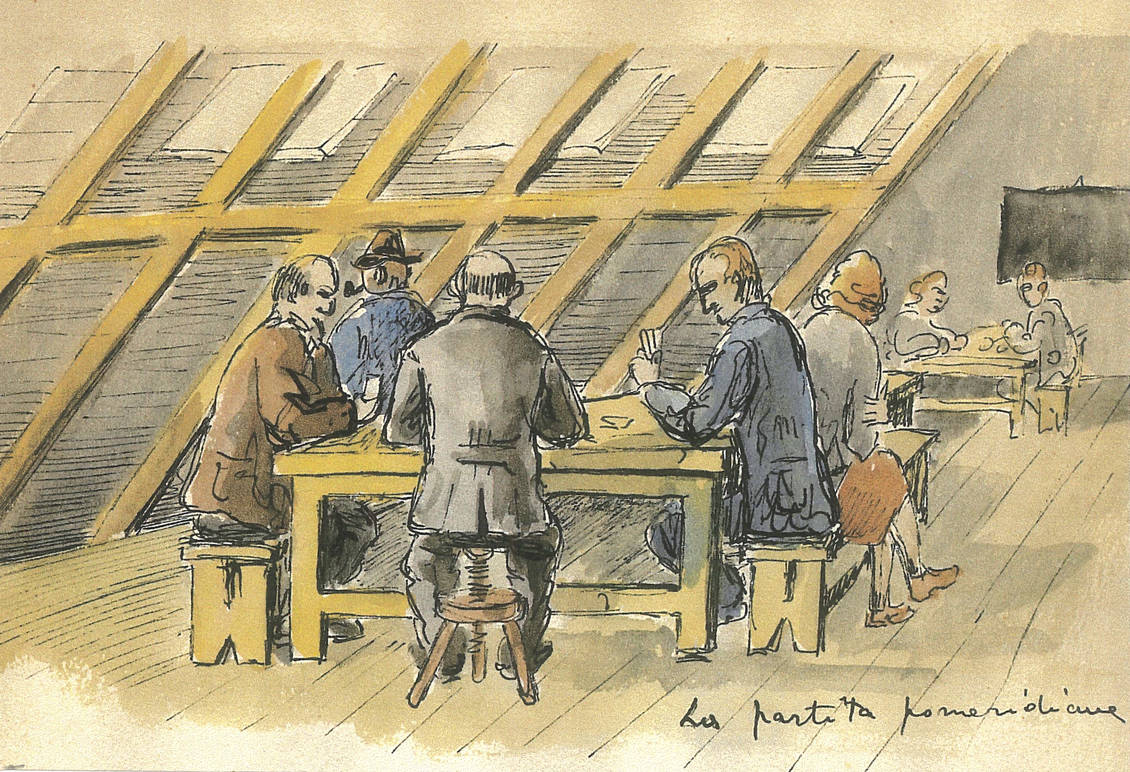

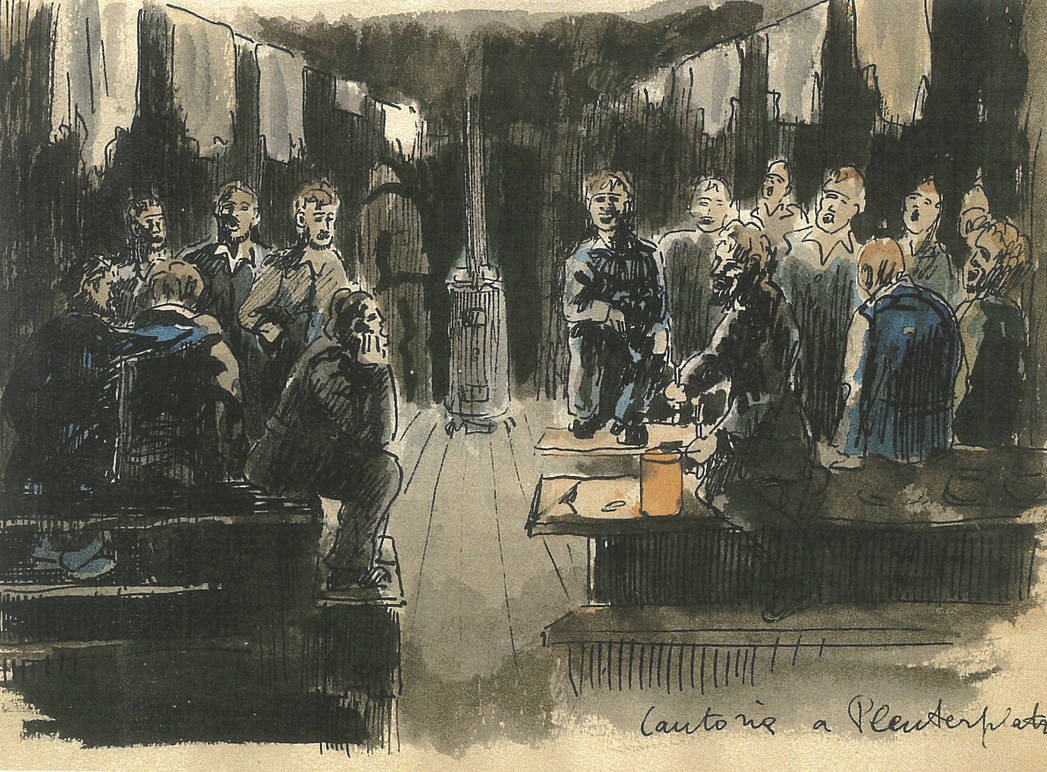

Eventually, with the help of a guide, he made it to Lugano, where he was arrested and put into jail until his request for asylum was approved and he was moved to the internment camp of Unterwalden. There, Leo drew and wrote every day, creating a rare record of daily life in the camp through his daily activities, interactions, and through his feelings.

After the war ended, Leo found himself alone and with nowhere to go. The chances of obtaining Italian citizenship were remote, as the country was in great turmoil. So he decided to move to America. In 1946, he came to New York where he established himself as a designer and artist.

Despite his best efforts, Leo never managed to obtain Italian citizenship, Ms. Spiegel explains. “I knew him for over 20 years,” the minute but energetic retired schoolteacher says, “and I know how much this grieved him.” For this reason, ever since the artist passed away in 2011, she has been working painstackingly to gather documents and contact authorities to grant Leo posthumous Italian citizenship.

The documentation she has managed to assemble is impressive. She carries copies of the most important documents with her in a fully stuffed folder and has spoken to countless people across the world, from UN workers to diplomats.

“It was the Consulate who told me to come to the Casa,” she tells me. Here, she felt welcomed and says she’s pleased with how the exhibition turned out. “What stood out to you?” she asks me eagerly, making it clear how much she cares about its effectiveness, its impact.

As the director of Casa Italiana, Stefano Albertini noted, in a way, dedicating a show to Leo here, in the Italian House, is a way of recognizing his belonging to the country. Something, which he and countless other Italian Jews were unjustly denied during their lifetimes.

But, far from being done, Lillian is still set on getting Leo his citizenship. In her research, she came across a similar case and found there is indeed a precedent for recognizing posthumous Italian citizenship. And as I look at her sitting inside an office of the Casa Italiana, where she generously agreed to meet me, I know she won’t stop until she gets it.