Americordo. The Italian Jewish Exiles in the Americas

In the annals of the Jewish and Italian communities in America there is little mention, if any, of Italian Jews. Indeed, with hardly any major figures in the 19th century and fewer than two thousand individuals forced to emigrate in 1938 by the Fascist racial laws, the arrival of Italian Jews in the Americas is not a phenomenon that easily allows a general study. Since the 1990s, however, many memoirs have been published, and a story that does not quite fit categorization has begun to emerge.

Through the collection and publishing of interviews and documents, Americordo will offer access to the stories of this diverse group of expatriates, who embraced all fields of knowledge and expressed in many ways their love of Italy and ties to their new homeland, yet always eluded ethnic identification.

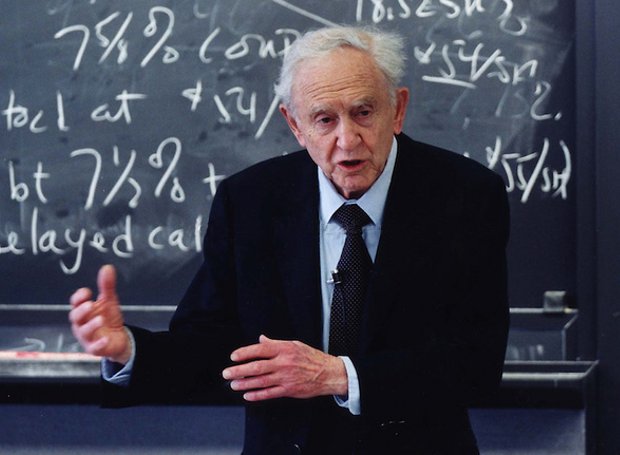

Jews who were forced to this country by the Fascist persecutions continued their work in fields ranging from mathematics and biology, Tullia e Bruno Zevi, Giorgio Cavaglieri, Amalia Rosselli, Silvano Arieti, Emilio Segré, Franco Modigliani, Paolo Milano, and Giorgio Levi della Vida are only a few of this group whose impact on society and people goes well beyond the four Nobel prizes they collected in the years after World War II. Not always coalescing as a community, Italian Jews nevertheless continue to share the humanistic heritage of their country of origin, and to participate in societal values and ideas that go beyond ethnic and religious particularism.

Essays

Memoirs

Bibliography

Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Conseguenze culturali delle leggi razziali in Italia, conference proceeding (Rome:1990).

Archivio Storico della Comunità Ebraica di Roma, Gli effetti delle leggi razziali sulle attività economiche degli ebrei nella città di Roma (1938–1943) (Rome: 2004).

Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri, Anselmi Report on the Confiscation of Jewish Assets, 2001.

Annalisa Capristo, L’espulsione degli ebrei dalle accademie italiane (Torino: Zamorani, 2002).

Annalisa Capristo, Arnaldo Momigliano e il mancato asilo negli USA (1938–1941). “I always hope that something will be found in America,” in «Quaderni di Storia», n. 62, January-June 2006.

Annalisa Capristo, Il decreto legge del 5 settembre 1938 e le altre norme antiebraiche nelle scuole, nelle università e nelle accademie, in «La rassegna mensile di Israel», 73, n. 2, May-August 2007.

Annalisa Capristo, L’esclusione degli ebrei dall’Accademia d’Italia, in «La rassegna mensile di Israel», 67, n. 3, 2001.

Annalisa Capristo, Tullio Levi-Civita e l’Accademia d’Italia, in «La rassegna mensile di Israel» 69, n. 1, 2003 (special issue: Saggi sull’ebraismo italiano del Novecento in onore di Luisella Mortara Ottolenghi, curated by Liliana Picciotto).

Annalisa Capristo, The Exclusion of Jews from Italian Academies, in Jews in Italy Under Fascist and Nazi Rule, 1922–1945 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Annalisa Capristo, Il coinvolgimento delle accademie e delle istituzioni culturali nella politica antiebraica del fascismo, in Università e accademie negli anni del Fascismo e del Nazismo, conference proceedings (Torino, May 11–13, 2005), edited by Pier Giorgio Zunino (Firenze: Leo S. Olschki, 2008).

Annalisa Capristo, “Acquiescence and Dissent: The Response of Intellectuals to the Fascist Racial Laws in Italy and Abroad,” in Printed Matter (CPLNY, 2009).

Annalisa Capristo, Le accademie italiane di fronte all’espulsione dei soci ebrei, in Le leggi antiebraiche del 1938, le società scienti che e la scuola in Italia, conference proceedings, Rome, November 26–28, 2008, Accademia Nazionale delle Scienze, n. XL, Rome, 2009.

Tommaso Dell’Era, “La storiogra a sull’università italiana e la persecuzione antiebraica,” in Qualestoria, 32, n. 2, 2004.

John P. Diggins, Mussolini and Fascism: The View from America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972, 2015).

Roberto Finzi, L’università italiana e le leggi antiebraiche (Roma: Editori Riuniti, 2003).

Carla Forti, Il caso Pardo Roques: Un eccidio del 1944 tra memoria e oblio (Torino: Einaudi, 1998).

Valeria Gallimi, Giovanna Procacci, “Per la difesa della razza.” L’applicazione delle leggi antiebraiche nelle università italiane (Milano: Unicopli, 2009).

Alessandra Gissi, L’emigrazione dei “maestri.” Gli scienziati italiani negli Stati Uniti tra le due guerre, in Donne e uomini migranti. Storie e geogra e tra breve e lunga distanza, a cura di A. Arru, D.L. Caglioti, F. Ramella (Roma: Donzelli, 2008).

Michael A. Livingston, The Fascists and the Jews of Italy Mussolini’s Race Laws, 1938–1943 (London, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

David Kertzer, The Pope and Mussolini: The Secret History of Pius XI and the Rise of Fascism in Europe (New York: Random House 2014).

Luisa Passerini , Women and Men in Love: European Identities in the 20th Century (New York: Berghahn Books, 2012).

Francesca Pelini-Ilaria Pavan, La doppia epurazione. L’Università di Pisa e le leggi razziali tra guerra e dopoguerra (Bologna: Il Mulino, 2009). Gabriele Rigano, “Storia, memoria e bibliogra a delle leggi razziste in Italia,” in Marina Beer, Anna Foa, Isabella Iannuzzi, Leggi del 1938 e cultura del razzismo. Storia, memoria, rimozione (Rome: Viella, 2010).

Harvey Sachs, Music in Fascist Italy (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1987).

Michele Sarfatti, 1938: le leggi contro gli ebrei, numero speciale della «La rassegna mensile di Israel», 54, n. 1–2, 1988.

Michele Sarfatti, Mussolini contro gli ebrei. Cronaca dell’elaborazione delle leggi del 1938 (Torino: Zamorani, 1994).

Michele Sarfatti, The Jews in Mussolini’s Italy, From Equality to Persecution, Translated by John and Anne C. Tedeschi (Madison: Wisconsin University Press, 2006).

Guri Schwarz, Interpreting fascist anti-Semitism. Jewish memories and the scholarly debate in Italy, from Liberation to the present, in Beyond camps and forced labour. Current international research on survivors of Nazi persecution. Proceedings of the rst international multidisciplinary conference at the Imperial War Museum, London, 29–31 January 2003, Johannes-Dieter Steinert Inge Weber-Newth, Osnabrück, Secolo, 2005.

Guri Schwarz, After Mussolini: Jewish Life and Jewish Memories in Post-Fascist Italy, translated by Giovanni Noor Mazhar (Portland: Valentine Mitchell, 2012).

Gianni Scipioni Rossi, La destra e gli ebrei (Catanzaro: Rubbettino Editore, 2003).

Gabriele Turi, Lo Stato Educatore. Politica e intellettuali nell’Italia fascista (Roma-Bari: Laterza, 2002).

Angelo Ventura, “La persecuzione fascista contro gli ebrei nell’Università italiana,” in Rivista storica italiana, 109, n. 1, 1997.

Klaus Voigt, Il rifugio precario. Gli esuli in Italia dal 1933 al 1945 (Scandicci: La Nuova Italia, 1993–1996) (ed. or.: Zu aucht auf Widerruf. Exil in Italien 1933–1945. (Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 1989–1993).

Tullia Zevi, “L’emigrazione razziale,” in Antonio Varsori, L’antifascismo italiano negli Stati Uniti durante la Seconda guerra mondiale (Roma: Archivio Trimestrale, 1984).

James A. Arieti, Memories of the son of a psychiatrist, «Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis», n. 4, 1999, pp. 541–550. Lino

Belleggia, Lettore di professione fra Italia e Stati Uniti: Saggio su Paolo Milano (Roma: Bulzoni, 2000).

Fabio Benzi (ed.), Corrado Cagli e il suo magistero: mezzo secolo di arte italiana dalla Scuola romana all’astrattismo (Milano: Skira, 2010).

R. Stephen Berry, Mitio Inokuti, A. R. P. Rau, Ugo Fano 1912–2001, A Biographical Memoir, Washington, DC, National Academy of Sciences, 2009.

Giulio L. Cantoni, From Milano to New York by way of hell (San Josè: Writers Club Press, 2000).

Antonio Cassarà, “Il maestro Vittorio Rieti amato negli USA e sconosciuto in Italia. Il racconto di una vita da ebreo perseguitato in una lunga intervista,” in Patria indipendente, 20 giugno 2010, pp. 40–43.

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Una vita di musica (Fiesole: Cadmo, 2005). Annie Cohen-Solal, Leo and His Circle: The Life of Leo Castelli (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010).

David Y. Cooper, “Luria, Salvador Edward,” in American National Biography (Oxford-New York: Oxford University Press, 1999).

Richard N. Gardner, Mission: Italy (Milano: Mondadori, 2004).

Claudio Gerbi, Out of the Past. A Story of the Gerbi Family, copyright 1987 (unpublished), CPLNY.

Ugo Fano, “The Memories of an Atomic Physicist for my Children and Grandchildren,” in Physics Essays, vol. 13, n. 2, June 2000, pp. 176–197.

Laura Capon Fermi, Atoms in the Family: My Life with Enrico Fermi (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1954).

Laura Fermi, Illustrious Immigrants. The Intellectual Migration from Europe, 1930–41 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968) Olivia Fermi, Laura Fermi’s life, in The Fermi Effect. A living legacy project, www.fermieffect.com

J. David Jackson, Emilio Gino Segrè 1905–1989: A Biographical Memoir (Washington, D.C.: The National Academy Press, 2002).

Alan Jones, Leo Castelli: l’italiano ch inventò l’arte in America (Roma: Castelvecchi, 2007).

Suzannah Lessard, “A Kind of Dancer” in The New Yorker, Jan. 9, 1989. Giorgio Levi Della Vida, Arabi ed ebrei nella storia (Napoli: Guida Editori, 1984).

Giorgio Levi Della Vida, Fantasmi Ritrovati (Napoli: Liguori Editore, 2004).

Salvador E. Luria, A Slot Machine, a Broken Test Tube: An Autobiography (New York: Harper & Row, 1984). 324

Franco Milano, Memories, 2002 (unpublished), CPLNY.

Paolo Milano, Note a margine a una vita assente (Milano: Adelphi, 1991). Franco Modigliani, Adventures of an Economist (New York-London: Texere, 2001).

Rita Levi Montalcini, In Praise of Imperfection (New York: Basic Books, 1988).

Gualtiero Morpurgo, Il Violino Rifugiato (Milano: Mursia, 2006).

Carla Pekelis, My Version of the Facts, translated by George Hoch eld (Chicago: Marlboro Press, 2005).

Franco Carlo Ricci, Vittorio Rieti (Napoli-Roma: Edizioni Scienti che Italiane, 1987).

Bruno Rossi, Moments in the Life of a Scientist (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

Nick Rossi, “A tale of two countries. The operas of Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco,” in Opera Quarterly, vol. VII, 1990, pp. 89–122.

Harvey Sachs (curator), Arturo Toscanini, dal 1915 al 1946. L’arte all’ombra della politica: omaggio al maestro a 30 anni dalla scomparsa,

Exhibition catalogue (Torino: Ed. Musica, 1987). Harvey Sachs, ed., The letters of Arturo Toscanini (London: Faber and Faber, 2002).

Gaetano Salvemini, Ricordi di un Fuoriuscito (Milano: Feltrinelli, 1960).

Emilio Segrè, A Mind Always in Motion: The Autobiography of Emilio Segre (Oakland: University of California Press, 1993).

Alexander Stille, The Force of Things: A Marriage in War and Peace (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013).

Peter G. Treves, La ne di un’era (New York: Treves Publishing Company, 1992).

Andrew J. Viterbi, Reflections of an Educator, Researcher and Entrepreneur, CPL Editions 2016

Tullia Zevi-Nathania Zevi, Ti racconto la mia storia (Milano: Rizzoli, 2007).

Patrizia Audenino, Il prezzo della libertà: Gaetano Salvemini in esilio (1925–1949) (Catanzaro: Rubbettino, 2009).

Peter Bacon Hales, Atomic Spaces: Living on the Manhattan Project (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997).

Richard Breitman and Alan M. Kraut, American Refugee Policy and European Jewry, 1933–1945 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987).

Richard Breitman and Allan J. Lichtman, FDR and the Jews (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013).

Philip V. Cannistraro, Blackshirts in Little Italy: Italian-Americans and Fascism, 1921–1929 (New York: Bordighera Press, 1999).

Renato Camurri, “Idee in movimento. L’esilio degli intellettuali italiani negli Stati Uniti (1930–1945),” in Memoria e Ricerca, n. 31, May– August 2009.

Renato Camurri, Un intellettuale cosmpolita. Introduzione a Franco Modigliani, L’Italia vista dall’America: Battaglie e ri essioni di un esule (Torino: Bollati Boringhieri, 2010).

Renato Camurri, “A forgotten generation: Italian cultural migration to the Americas (1930–45),” in Journal of Modern Italian Studies, Vol. 15, N. 5, 2010.

Renato Camurri, “Max Ascoli and Italian intellectuals in exile in the United States before the second World War,” Journal of Modern Italian Studies, Vol. 15 N. 5, 2010.

Leonard Dinnerstein, Antisemitism in America (New York-Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994).

Giuliana Gemelli (ed.), «The Unacceptables»: American Foundations and Refugee Scholars Between the Two World Wars and After (Bruxelles: P. Lang, 2000).

Sandro Gerbi, “La sezione italiana della Voce dell’America, 1942–1945,” Belfagor, LXVI, n.1, Janurat 31, 2011.

Ellen Ginzburg Migliorino, “Italian Jews in the United States in the Early 40s: Impressions and Lifestyle Changes” (pp. 267–275) in America and the Mediterranean, edited by M. Bacigalupo and P. Castagneto AISNA, Genova, 2001.

Ellen Ginzburg Migliorino, Dopo le leggi razziali. Gli ebrei italiani in America: prime impressioni (University of Trieste: Sissco conference, Lecco, September 27, 2003).

Henry L. Feingold, The Politics of Rescue (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1970).

Laura Fermi, Illustrious Immigrants. The Intellectual Migration from Europe, 1930–1941 (Chicago-London: University of Chicago Press, 1968).

Domenico Fracchiolla, Un ambasciatore della Nuova Italia a Washington, Alberto Tarchiani e le relazioni tra l’Italia e gli Stati Uniti 1945–1947 (Milano: Franco Angeli, 2012).

Daniela Gagliani, Il difficile rientro. Il ritorno dei docenti ebrei nell’Università del dopoguerra (Bologna: CLUEB, 2004).

Davide Grippa, Un antifascista tra Italia e Stati Uniti: democrazia e identità nazionale nel pensiero di Max Ascoli (1898–1947) (Milano: Franco Angeli, 2009).

Leslie Grove, How it can be told. The story of the Manhattan Project (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1962).

Charles Killinger, Fighting Fascism from the Valley: Italian Intellectuals in the United States, in Peter I. Rose (ed.), The Dispossessed: Anatomy of Exile (Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2005).

Stefano Luconi, La “diplomazia parallela.” Il regime fascista e la mobilitazione politica degli italo-americani (Milano: Franco Angeli, 2000).

Stefano Luconi and Guido Tintori, L’ombra lunga del fascio. Canali di propaganda fascista per gli “italiani d’America” (Milano: M&B Publishing, 2004).

Stefano Luconi, “Generoso Pope and Italian-American Voters in New York City,” Studi Emigrazione, 38, June 2001.

Stefano Luconi, “The Voice of the Motherland: Pro-Fascist Broadcasts for the Italian-American Communities in the United States,” Journal of Radio Studies, 8, Summer 2001.

Stefano Luconi, “Fascist Antisemitism and Jewish-Italian Relations in the United States,” American Jewish Archives Journal, 56, 2004.

Lamberto Mercuri, Mazzini news. Organo della «Mazzini society» (1941–42) (Foggia: Bastogi Editrice Italiana, 1990).

Egidio Ortona, Anni d’America. La ricostruzione 1944–1951 (Bologna: Il Mulino, 1984).

Monty Noam Penkower, The Jews were expendable (Urbana: Chicago University of Illinois Press, 1983).

Matteo Pretelli, “Fascismo e Giovani Italiani all’estero” in Patrizia Dogliani (ed.), Giovani e generazioni nel mondo contemporaneo (Bologna: CLUEB 2009).

Matteo Pretelli, “Tra estremismo e moderazione. Il ruolo dei circoli fascisti italo-americaninella politica estera italiana degli anni Trenta” in Studi Emigrazione, XXXX, n. 150, 2003.

Matteo Pretelli, “Culture or Propaganda? Fascism and Italian Culture in the United States” in Studi Emigrazione, XLIII, n. 161, 2006.

Giuseppe Prezzolini, America in pantofole (Firenze: Vallecchi, 1950).

Bruce Cameron Reed, The History and Science of the Manhattan Project (New York: Springer, 2013).

Gaetano Salvemini, Italian Fascist Activities in the United States, 1940. Republished in Center for Migration Studies Special Issues, Vol. 3 N. 3, 1977 and available through the Wiley Online Library.

Holly Cowan Shulman, The Voice of America: Propaganda and Democracy, 1941–1945 (Madison: Wisconsin University Press, 1990).

Alberto Tarchiani, Dieci anni tra Roma e Washington (Milano: Mondadori, 1955).

Maddalena Tirabassi-Patrizia Audenino, Migrazioni italiane. Storia e storie dall’Ancien Régime a oggi (Milano: Mondadori, 2008).

Maddalena Tirabassi, “Nazioni Unite (1942–1946): l’organo ufficiale della Mazzini Society” in L’antifascismo italiano negli Stati Uniti durante la Seconda guerra mondiale, Rome, Archivio trimestrale, 1984.

Maddalena Tirabassi, “La Mazzini Society (1940–46): un’associazione di antifascisti italiani negli Stati Uniti” in Giorgio Spini, Gian Giacomo Migone, Massimo Teodori, Italia e America dalla Grande Guerra ad Oggi (Venezia: Marsilio, 1976).

Maddalena Tirabassi, “Enemy Aliens or Loyal Americans? The Mazzini Society and the Italian-American Communities” in Rivista di Studi Anglo-Americani, 4–5, 1984–85.

Mario Toscano, L’emigrazione ebraica italiana dopo il 1938, ora in Mario Toscano, Ebraismo e antisemitismo in Italia (Milano: Franco Angeli, 2003).

Rosario J. Tosiello, “Max Ascoli. A Lifetime of Rockefeller Connections” in Giuliana Gemelli (ed.), The Unacceptables. American Foundations and Refugee Scholars between the Two World Wars and After (Bruxelles: P. Lang, 2000).

Antonio Varsori, Antifascismo negli Stati Uniti e comunità Italo-Americana (Firenze: Sansoni, 1982).

Antonio Varsori, Gli alleati e l’emigrazione democratica antifascista 1940–1943 (Firenze: Sansoni, 1982)

Antonio Varsori, “La Mazzini Society” in Nuova Antologia, CXV, n. 2136, 1980.

Alan L. Heil Jr., Alan Heil, Voice of America (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006).

Allan M. Winkler, The Politics of propaganda: The of ce of war information, 1942–1945 (New Haven-London: Yale University Press, 1978).

David S. Wyman, Paper Walls: America and the Refugee Crisis 1938–1941, Rev. ed. (New York: Pantheon Books, 1985)

Francesco Cassata, Building the New Man: Eugenics, Racial Science and Genetics in Twentieth-century Italy (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2011).

Helmut Goetz, Il giuramento rifiutato: I docenti universitari e il regime fascista, trans. Loredana Melissari (Firenze: La Nuova Italia, 2000).

Giorgio Israel; Pietro Nastasi, Scienza e razza nell’Italia fascista (Bologna: Il Mulino, 1998).

Giorgio Israel, Il fascismo e la razza. La scienza italiana e le politiche razziali del regime (Bologna: Il Mulino, 2010).

Roberto Maiocchi, Gli scienziati del duce : il ruolo dei ricercatori e del CNR nella politica autarchica del fascism (Rome: Carocci, 2004).

Pietro Nastasi, Angelo Guerreggio, Matematica in camicia nera: il regime e gli scienziati (Milano: Mondadori, 2005).

Judith R. Goodstein, The Volterra Chronicles: The Life and Times of an Extraordinary Mathematician, 1860–1940 (Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society, 2007).

Angelo Guerraggio and Giovanni Paoloni, Vito Volterra, trans. Kim Williams (Heidelberg-New York: Springer, 2012).

Valeria Galimi, Giovanna Procacci (eds.), Per la difesa della razza: l’applicazione delle leggi antiebraiche nelle università italiane (Milano: Unicopli: 2009).

Gabriele Turi, Lo Stato educatore. Politica e intellettuali nell’Italia fascista (Roma-Bari: Laterza, 2002).

Patrizia Guarnieri, Senza cattedra: L’Istituto di Psicologia dell’Università di Firenze tra idealismo e fascismo (Firenze: Firenze University Press, 2012).

Raffaella Simili, Sotto falso nome: Scienziate italiane ebree (1938–1945) (Bologna: Pendragon, 2010).

Angelo Ventura (ed.), L’Università dalle leggi razziali alla Resistenza (Padoa: Padova University Press, 1996).

Interviews by Gianna Pontecorboli. These interviews were conducted by Gianna Pontecorboli for her book Americordo, The Italian Jewish Exiles in America, published in English by CPL Editions in 2015.

Ada Siegal, March 2008, New York

Alberta Eisenmann, April 2009, New York

Andrew Viterbi, September 2009 New York,

Anna Funaro, w/d

Silvana Sonnino, January 2008, Larchmont, NY

Bruno Pavia, August 2010, Milan

Clotilde Treves, May 2008, New York

Enzo Falco, October 2008, Boston

Eugenio Calabi, June 2008, Philadelphia

Fratelli Leoni, October 2008, Miami

Gigliola Colombo Lopez, August 2010, Milan

Giorgio Pavia, May 2010, New York

Giuliana Segrè Calabi, June 2008, Philadelphia

Giulio Bemporad, May 2008, Long Island, NY

Guido Calabresi, March 2009, New Haven, CT

Lina Vitale, May 2007, New York

Sheldon Satlin, October 2012, New York

Lloyd Levi, September 2007, New York

Magda Marchfeld, October, 2007 Nyack, NY

Marina Stern, May 2009, New York

Mirella Bedarida, September 2009, New York

Nora Lombroso Rossi, October 2008, New York

Robert Fano, October 2008, Boston

Tullia Zevi, October 2009, Rome

Willy Barta, October 2008, Miami

Memoirs

Giorgio Cavalieri, Memories of life in the twentieth century. Emigration and World War II, typewritten documents donated by the author to CPL in 1999

Claudio Gerbi, M. D., Out of the past. A story of the Gerbi Family, unpublished.

Andrea Lager, Memoir, Typewritten documents donated by the author to CPL

Cathy Lager Bottone, In the Corner of the Carnaro… We were too few to make history, Typewritten documents donated by the author to CPL and reviewed by her son

Peter G. Treves, “This I remember”, “The War Years”, 1939-1946, Vol. II, Palm Beach, New York 1988-1989, unpublished.

Vera De Benedetti Bonnet, The summer House, unpublished.

Ellen Ginzburg Migliorno, Dopo le leggi razziali. Gli ebrei italiani in America: prime impressioni, Università di Trieste, unpublished.

Essential history

Enrico Fermi, whose wife, Laura Capon and children were Jewish. Fermi gave some international resonance to the situation in Italy by fleeing the country with his family after receiving the Nobel Prize in 1938, a few days after after Kristallnacht.

Enrico Fermi, whose wife, Laura Capon and children were Jewish. Fermi gave some international resonance to the situation in Italy by fleeing the country with his family after receiving the Nobel Prize in 1938, a few days after after Kristallnacht.