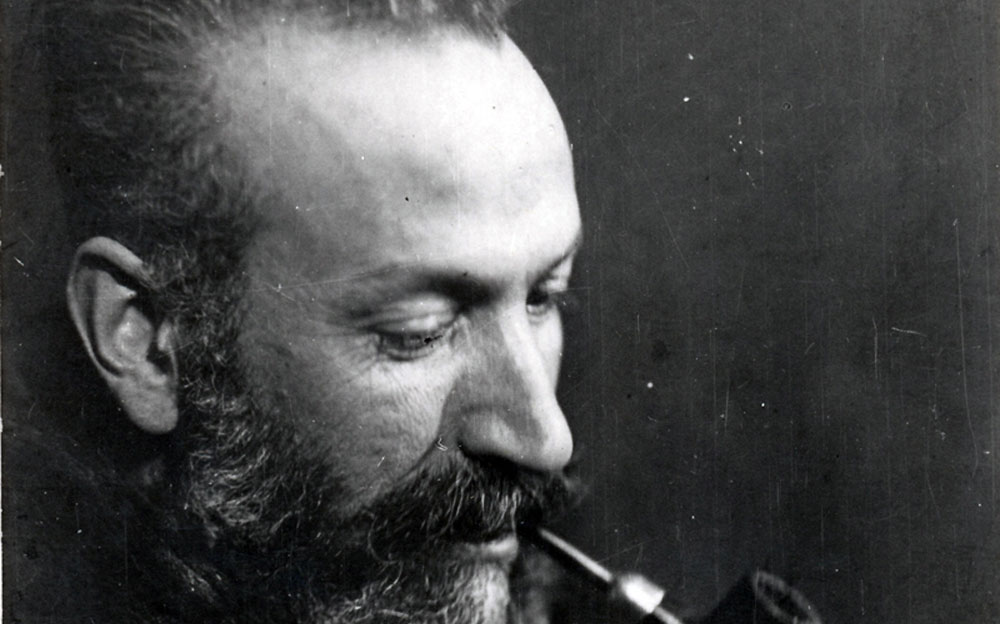

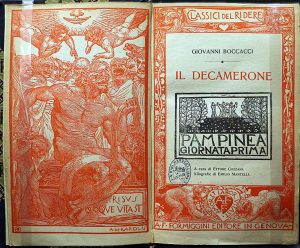

Born in Modena to a family of court jewelers who had maintained their private synagogue for generations, Angelo Fortunato Formiggini (1878–1938) was a publisher first in Modena (1908–11), then in Genoa (1911–15), in Bologna; and finally in Rome, where he won prominence for his innovations in publishing and the quality of his books. His Classici del ridere (1913 to 1938), include humor classics ranging from Boccaccio and François Rabelais to Voltaire, Honoré de Balzac, Jonathan Swift, William Thackeray, and Shalom Aleichem. He created Who’s Who, a dictionary of contemporary Italians, and served as managing editor of L’Italia che scrive, a monthly review of Italian literary and artistic activities, bibliography, and intellectual debate. Between 1919 and 1921 he founded the Italian Institute for Cultural Propaganda Abroad and in 1929 he planned and organized the World Congress of Libraries and Bibliography. When the antisemitic laws of 1938 were promulgated, he committed suicide by jumping off the tower of Ghirlandina in Modena as an act of extreme protest and rebellion. His spiritual testament Parole in libertà was published posthumously (1945).

Tutto

avrei potuto credere

tranne che diventare

un martire della umanità.

È un mestiere che non mi piace: preferivo

i “Classici del Ridere”.

Eliza Pederzoli’s biography L’arte di farsi conoscere. Formiggini e la diffusione del libro e della cultura italiana nel mondo (Roma, Associazione Italiana Biblioteche, 2019) offers an in-depth survey of the archival resources on the history of one of Italy’s most innovative publishers. Reviewed by Annalisa Capristo.

Elisa Pederzoli’s, “The Art of Making Oneself Known.” Formiggini and the Promotion of Italian Books and Culture in the World (Rome 2019) is an interesting book. The result of research conducted between Italy and the United States for her doctoral dissertation, Pederzoli’s work received the “Giorgio De Gregori” Award in 2018. It was published by the Italian Libraries Association, with a preface by Paolo Tinti of the University of Bologna.

The volume is based on the rich documentation preserved in Italian and American archives, until now largely unexplored. Particularly noteworthy are what Formiggini called the “archive of reviews,” a section of the Formiggini Publisher papers he bequeathed to the Estense Library of Modena, and the documents at the Columbia University Archives in New York.

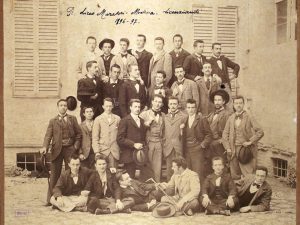

As Tinti points out in his preface in describing the activities of Formiggini, one of Italy’s most refined publishers, Pederzoli highlights his international vocation and universalistic inspiration, the “passionate secular humanism” which animated Formiggini since his youth as a member of the international student association Corda Fratres.

On this topic, reflecting on what Formiggini wrote in his proposal for the Institute of Italian Cultural Propaganda Abroad written for the Foreign Minister in 1919, the author explains how the Modenese publisher had taken on the task of “promoting our national thought among civilized peoples, […] not with imperialistic intentions but only to show ourselves as deserving of the sympathy and respect of all peoples.” And Pederzoli observes that it was precisely “the refusal to fuel cultural promotion with any intent of prevarication or imposition” that caused “the first real clash between Formiggini and fascist totalitarianism, long before the rise of the racist policies.”

The author highlights various aspects of Formiggini’s biography. Some, perhaps less known facts, are truly striking, as they remind us of the vibrant debate on national identity, antisemitism, and Zionism current in the Italian cultural and political discourse between the 19th and 20th centuries. Of particular interest is the controversy over the “Jewish question” among the Corda Fratres, which, in 1905, led to Formiggini’s resignation as president of its Italian branch. Also of note, the analysis of Formiggini’s thesis for his Law degree in 1901: Women in the Thorà A Comparison with Mânava-Dharma-Sâstra. Historical-juridical Contribution to a Rapprochement Between the Aryan and Semitic Races, in which the future publisher addressed the relationship between Semitic and Aryan/Indian thought, suggesting “that Semites and Aryans were, in the remote past, the same people, or two peoples with similar evolutionary potential”. The text, previously mentioned by Antonio Castronuovo in “Belfagor” (2008), is preserved in Modena’s Estense Library. Another relevant issue discussed in the book is Formiggini’s role in Freemasonry.

Expanding on the question of representation and identity, Pederzoli refers to an episode from 1924, when Formiggini decided not to publish a volume of “Jewish or Yiddish stories,” written in the vein of the French Histoires juives. The book had been proposed to him by the translator Ada Cippitelli Salvatore. Quoting from the correspondence preserved in the publisher’s archive, Pederzoli comments: “For a Jewish publisher to produce such a volume seemed to Formiggini a high-risk exposure which he preferred to avoid.”

Formiggini’s intelligence and highly cultivated personality emerge abundantly from this book, and precisely concerning his international vision which lead him, for instance, to translate and distribute abroad his series” Apologie,” dedicated to cultural and religious topics circulating in Italy. The Apology of Judaism (published in 1925) was entrusted to the Zionist rabbi Dante Lattes and that of Catholicism to Ernesto Buonaiuti (1923), whose disagreements with the Catholic authorities were already at a very advanced stage. The Apology of Atheism and that of Skepticism (1925-1926) were written by Giuseppe Rensi, a philosopher who openly opposed Fascism after the Matteotti murder.

The translation project encountered difficulties and eventually stalled. While the volumes on Judaism, Paganism, Buddhism, and Taoism were translated into French; the one on Protestantism in Spanish; and the Apology of Judaism in Portuguese, Rensi’s volume on Atheism did not make it into French, and not a single book of of the series was translated into German or Greek. All attempts to translate the series into English also failed, both in Great Britain and the United States.

In the same years, Formiggini managed to establish relationships and exchanges with Americans living in Italy. One of them was H. Nelson Gay, a scholar of the Risorgimento who settled in Rome at the end of the 19th century. In 1918, he founded the Library for American Studies in Italy, at the time based in Palazzo Salviati al Corso, that which he directed until his death in 1932.

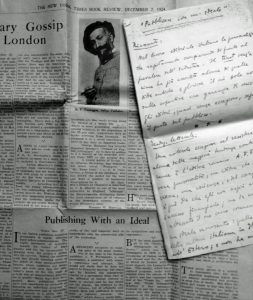

The two men’s mutual admiration transpires in their exchange of public praises: the 1923 extensive presentation of the new American Library in Formiggini’s prestigious magazine L’Italia che scrive by the scholar of Christianity, Alberto Pincherle; and Nelson Gay’s profile of Formiggini, Publishing with an ideal, in which he defines the Italian publisher “a twentieth century’s Viesseaux.” Illustrated by a prominently laid out photograph, the flattering piece appeared in the “New York Times Book Review” on December 7, 1924.

The Modenese publisher’s relations with the United States went further. In 1928, Formiggini participated in the first Italian Book Exhibition organized by the Casa Italiana at Columbia University in New York. The Casa was inaugurated in 1927 and, in 1930, Giuseppe Prezzolini became its director. As Pederzoli points out, in the section called “Politics and Sociology” of the New York bibliographic exhibition, only two titles published by Formiggini were included: Dal Socialismo al Fascismo by Ivanoe Bonomi (1924) and the Battaglie giornalistiche by Benito Mussolini (1927): “the two texts represented […] two contrasting visions of the fascist regime: the lucid criticism of Bonomi on the one hand, the voice of the Duce on the other. The choice could represent the umpteenth attempt by Formiggini to demonstrate the neutrality of the publishing house within the delicate balance of power emerging in the Italian cultural landscape. At the same time, the inclusion of Mussolini’s volume seemed to testify that there was not a total closure towards the regime”.

Here unfolds the central theme of Formiggini’s personal and professional biography: the problem of his relationship with Fascism, which the Modenese publisher had to confront during the 1920s and 1930s, up to the tragic outcome of 1938. As well known, and as Pederzoli amply illustrates, between 1922 and 1923, under pressure from philosopher and Minister of Public Education Giovanni Gentile, Formiggini was completely excluded from the Fondazione Leonardo for Italian culture (as the former Institute for the promotion of Italian culture was renamed) and from the project of the Grande Enciclopedia Italiana that had previously been entrusted to him. This political publishing shift resulted in the establishment, in 1925, of the Institute of the Italian Encyclopedia, of which Gentile became scientific director, and the publication of the Italian Encyclopedia of Sciences, Letters and Arts. The exclusion was, for Formiggini, a source of great affliction. Undoubtedly without him, the project changed radically. It is difficult to say whether, with Formiggini at the helm, it would have been as authoritative, but it would have certainly been much less “regime-driven” (albeit of the highest cultural level) than it turned out to be.

The question of Formiggini’s relationship with the Regime is, from all points of view, central to his biography. In the book, Pederzoli shows, with great breadth of references, that Formiggini’s ideal “of being able to pursue a single ‘book policy’ and remain above politics itself” was utterly unrealistic. In 1938 the tragic epilogue came: his publishing house was one of the most affected by the anti-Jewish measures. As Giorgio Fabre documented (The List. Fascist censorship, Jewish publishing and authors, 1998), Formiggini’s suicide occurred after “an escalation of humiliating and disastrous news” and under extreme pressure. Not only was Formiggini himself forced to report the names of the “Jewish” authors present in his catalog, but he was also ordered to change the name of his publishing house, which meant reducing its value and making it even more difficult to sell. A further mockery on the part of the fascist authorities was the use of the famous bio-bibliographic dictionary published by Formiggini (Who’s Who?) to identify the Jewish authors who had to be eliminated from the Italian publishing scene (Fabre, The List).

Ultimately, this brilliant and cosmopolitan protagonist of Italian culture chose suicide as the extreme and only possible form of protest against the complete cancellation of the Jewish contribution decided by the regime.

Some resources about Angelo Fortunato Formiggini

J-Italy: Italian Jews and the history of publishing

Formiggini Papers at the Estense Library in Modena

A Publisher against Fascism: Angelo Fortunato Formiggini, Antonio Castronuovo