On the occasion of Berlinale 2024, Israeli director Amos Gitai presented «Shikun» a film that foreshadows the dark tension preceding October 7th. Amos Gitai’s cinema encompasses art, architecture, theatre, music, news, map, writing, research, physical gesture, political impetus, critical spirit; he works on form like few others, to probe the fragile substance of which reality is imprinted – the one that happens before our eyes – and which is also given such a rigid name. Gitai plays seriously, striking and provoking our gaze. In the beginning of Shikun, Irène Jacob advances through the catastrophe, along the seemingly infinite corridor of a council house, a communal place in which a host of refugees of various origins seek shelter, each fleeing from the “rhinoceros,” an invisible symbol of blind power, of conformism , of domination through fear.

As always, Gitai does not look for consoling answers, but asks uncomfortable questions, avoids judgment a tries to listen to the tragic dimension of events: in a bleak dialogue reported by Amira Hass between a girl and an elderly man, she asks «how could you do all this?, when will we be able to stop being ashamed of what you did?» The elderly ex-soldier replies «I only followed orders».

How do you feel after what happened on October 7th?

This conflict is a tragedy. A huge tragedy. The ferocity of Hamas’s actions, the destruction of kibbutzim, the murder of civilians, the killing of young people dancing at a concert, the acts of barbarism and the rape of women are atrocious acts. They are not only anti-Israeli, they are also anti-Palestinian, because they destroy the option of dialogue between the two peoples. The only possible perspective.

I listen to the speeches of those who put everything together, creating confusion, in this tragedy… But even a national resistance does not justify this type of barbarism and violence. Burning people alive, killing children in front of their parents… Nothing justifies this. It does nothing but delay the agreement between the Israeli and Palestinian people, because it is clear that a workable modus vivendi must be found between the two peoples. There is no other option.

The current vicious cycle makes one want to cry. Netanyahu’s government is made up of fundamentalists, members of the far right, racists, who carry out provocations in Jerusalem, on the Mount of Olives. For months, before October 7, hundreds of thousands of Israelis demonstrated every week against this government.

The feeling today is similar to that of 50 years ago. Unfortunately, history repeats itself. But the current cycle is worse than the one my generation experienced. Today a terrible ritual is being enacted, through bombing, wasting human lives and all the resources of this region for military conflict, again and again. It is an immense tragedy for the Palestinian civilians of Gaza, after the entire military and political establishment was humiliated by Hamas’ surprise attack. The current Israeli government thinks that the conflict can be resolved with a “balance of force.” But there will never be a permanent solution without a deep dialogue that takes into account the suffering of both sides.

These are very dark times. Nobody knows how it will end. But I believe we must maintain hope, the alternative would be nihilism, destruction, death. We must continue to try to chart a path of hope.

Your latest film, «Shikun», seems to speak very clearly about what is happening these days, despite having been filmed before. Can you tell us something more about it?

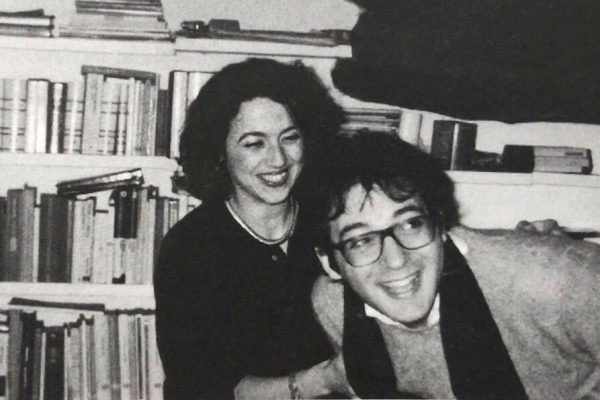

During the Yom Kippur War in 1973, I was part of a relief team. For us the enemy was death: we had to save people from death. As our helicopter flew over Syrian territory, I saw villages, jeeps and bases and that’s when a missile hit us and our helicopter crashed. From rescuers we have become victims. It took me twenty-seven years to make a fiction film about this experience (Kippur).

I am aware that I am only an individual in this vast mechanism, perhaps a witness, almost in the Hitchcockian sense of the term: in the sense of a witness to a crime. I wouldn’t talk about mission, but there is something that I have to translate through my gaze. I recently reread an exchange of letters between Albert Einstein and Sigmund Freud on the topic of “why war?” Shikun asks this question in the current context.

Faced with the abyss that separates Gaza and Israel today, what can cinema do?

Art may not be the most effective way to change reality, but it is a way to influence the way people think about war and conflict. I very often quote Picasso in relation to his masterpiece Guernica. And I believe, with due modesty, that our situation is similar. He was shocked by the Luftwaffe bombing of the Basque village of Guernica in 1937. His medium is painting, so he made a picture, so what happened will be remembered. It was essentially a civic gesture by Picasso, to transpose the fact into his midst. In the end, however, Picasso did not win. Franco and his dictatorship, which convinced Nazi Germany to bomb Guernica, won. For many years, Picasso’s Spanish republic lost. So art cannot instantly change reality. But Picasso won in the sense that Guernica is engraved in the memory. And I believe that our mission as artists is to impact memory.

I often say that I make films as a citizen, as a witness to the history of my country, a witness involved in what happens, as in House (1980, 1998, 2005), Kippur (2000) or The Last Day of Yitzhak Rabin (2015), about the assassination of the prime minister by a far-right Jewish student in 1995. When I made this film, it wasn’t just out of admiration for a political leader – they’re not people I usually admire, whether I’m in favor of or against their ideas – but out of respect for his sincerity, which is rare in politics. He could have been a general covered in victories, he was ready to go against the grain and look for solutions, and in this sense he was both a realist and a visionary.

Thirty years ago, he wanted to chart a course, propose a valid alternative in this very complicated Middle East. And he believed that telling the truth was the basis for moving forward. This effort was decapitated by his assassination.

This raises another question: What can we do? We writers, visual artists, painters, actors, filmmakers – is what we do totally useless? Because it is very likely that we will not be able to face such ferocious powers. Ferocious powers. Is it possible that we will lose? Yes, it is possible. Unfortunately it is also probable. But that doesn’t mean much right now.

At what point did Ionesco’s play “The Rhinos” emerge as a striking metaphor for the situation in Israel?

The film was born in relation to what the context was in Israel before October 7th. We were in the midst of a huge protest movement against Netanyahu and his far-right government’s attempt to reform the legal system, with large demonstrations bringing together feminist groups, soldiers, academics, economists, people fighting for coexistence peaceful between Palestinians and Israelis, and a large part of civil society. A movement that also had the sense of a reaction to the advance of a form of conformism, to the disappearance of critical thinking, in Israeli society. It is in this context that I reread Ionesco’s play Rhinoceros, written at the end of the 1950s, as an anti-totalitarian fairy tale, and which seemed to me to echo what we were experiencing. I saw in it the possibility of inspiring a film about the present we were living in.

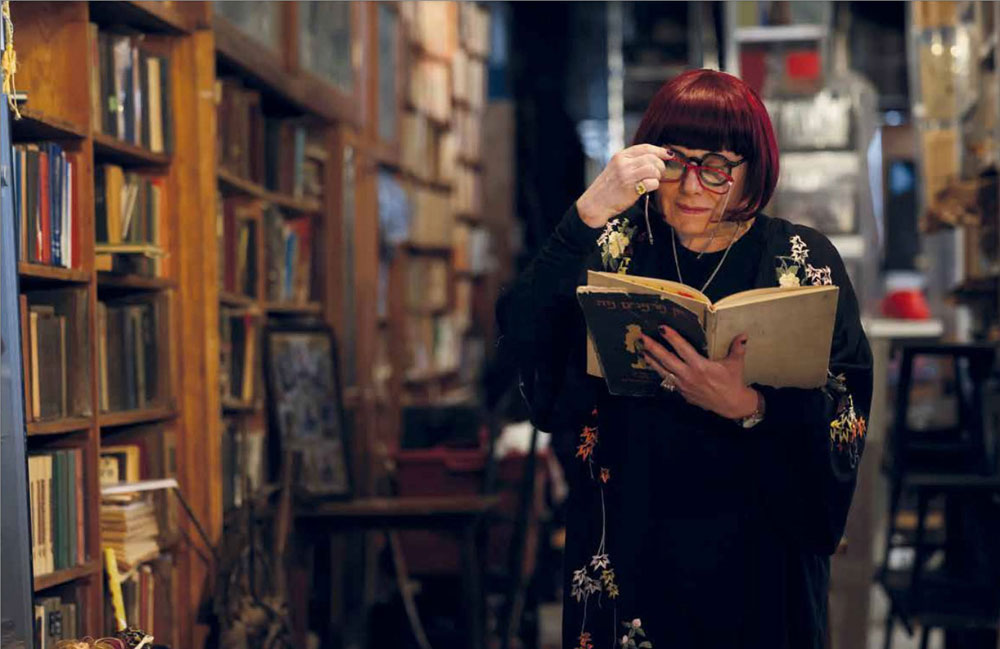

At the time I was rehearsing the theater version of House in Tel Aviv, a work inspired by my 1980 film. The whole cast was there, including Irène Jacob and the Palestinian actress Bahira Ablassi. In addition to working on the play, we collectively embarked on this project, which I wrote quite quickly. I called cinematographer Eric Gautier, who I’ve worked with on four of my previous films over the last twelve years, and he arrived right away. We managed to put together the material conditions and shoot without delays, thanks also to the complicity of the producers, technicians and artists with whom I have this long relationship of collaboration and friendship.

What is striking about «Shikun» is the form of the film, which seems to take place in a constant «in-between»: between inside and outside, between different languages, between the real and the absurd, between the unfinished construction and the ruin. You shot the film before October 7th, yet the “open” form of the film says precisely something drastic with respect to current events…

The film is about the chaos of the world, the chaos of war, economic inequality and injustice. Most films tend to sugarcoat this chaos by putting together explanations that reassure the audience. But in my opinion this is an illusion, a dishonesty. Reality is the result of heterogeneous forces, random events, illogical interferences. And in the midst of all this there is an active force, which is fear. Fear is not a fact, it is constructed, it is manufactured, and leaders like Trump, Netanyahu, Orban, Putin, etc. they are fear engineers, and of course so is Hamas. They thrive on the feeling of fear they produce and maintain. This is what rhinos metaphorically represent, and this is what we must resist.

My films are often juxtapositions of biographies, with memories of the past, romantic relationships, existential dilemmas, fractures of all kinds. Through this fragmentation, the characters try to build themselves and be coherent in a context that is inconsistent.

In Hebrew, «Shikun» means «public housing»; the building metaphor recalls one of your previous films, «House» (but also one of your first documentaries made for TV). Once again, you address the themes of exile and belonging through dwelling…

There was a debate about the title, between two options: the second was It’s Not Over Yet, based on the song from the film. My friends in Tel Aviv prefer the second title, which will also be the title of the film in Israel, but I prefer Shikun, which in Hebrew indicates a building, a place, in which to live. The word derives from a verb that means “to repair,” “to give shelter”. And the film shelters people who, for various reasons, need refuge from the threat of rhinos. I like the sound of the word. There is something abstract that I like, and it is in the spirit of the project.

This building, this shikun in which we shot, is a well-known construction, believed to be the longest building in the Middle East at over 250 meters. And it really is a shikun, a public housing building. It is located in the city of Beer-Sheva in the center of the Negev Desert in southern Israel. The building itself is a powerful architectural gesture, in the spirit of Le Corbusier, a sort of coup de force, of affirmation in the middle of the desert. Its spatial organization, perspectives, angles, construction materials helped me to make these different characters and these different activities, which can be in conflict or simply ignore each other, live in a contiguous way, without having to create artificial sequences, series of causes and effects as too many films force themselves to do. Each time it is about exploring a microcosm with the ambition that it reflects a more general truth. In the same way that studying one cell would provide a representation and information about an entire living body.

The different accents we hear in «Shikun» tell us about the scale of immigration coming to Israel: we hear people from Belarus, India and Ukraine speaking. Yet, towards the end, it is the Arabic language that makes its presence felt, through a poem by Mahmoud Darwish…

Most of the societies we live in are made up of men and women who have migrated from one place to another. Israel is one of the products of these exiles, with people from Central and Eastern Europe, North Africa and Ethiopia, not to mention the Palestinians who were exiled by the Israelis. Reality, however you look at it, is not coherent – architecturally, socially, economically or culturally. It does not even offer the illusion of unity: it is no longer the distant reality of a past unified by tradition, in which the individual was part of a community, of a succession of generations living in a continuum one after the other – it is a crumbled, totally fragmented reality. The experience of life in this broken reality is that of the stranger, of coincidence, of alienation and of the chance encounter. The experience offered by modern culture is that of juxtaposition – a sort of discontinuous neighborhood of slices of reality, a proximity that places people next to each other.