In 1948, Alba de Céspedes wrote to her friend, the acclaimed writer Natalia Ginzburg, of a specific kind of affliction that could befall the women of their time.

They called it a “well,” a “terrible melancholy” that women—still mostly confined to the domestic sphere in the immediate aftermath of WWII, not yet considered equal under the law—regularly experienced. An abstract, suffering feeling both universal and barely describable, specific to interiority. A sort of repressed mental state that could lead one to do something irrational. Perhaps today we would call it an emotional spiral.

“[Every] time we fall in the well we descend to the deepest roots of our being human,” De Céspedes wrote. “In returning to the surface we carry inside us the kinds of experiences that allow us to understand everything that men—who never fall into the well—will never understand.”

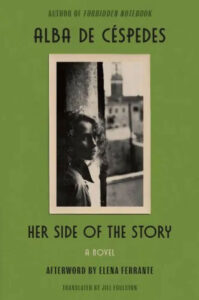

De Céspedes would take readers on a journey down the well in her 1949 novel Her Side of the Story, now available to English-speaking readers in a new translation by Jill Foulston.

In Her Side of The Story, a Roman woman named Alessandra Corteggiani recalls the story of her youth, family, and a great love amidst the backdrop of the rise of fascist Italy, World War II, and the resistance. Beneath this sprawling tale of “great love and crime” bubbles what is in equal measures a feminist social novel. One doesn’t have to dig too deep to find the political meaning within these pages—it is all at once a scathing indictment of patriarchy and a teardown of fascist ideals, delivered at a moment of impending societal shifts for women.

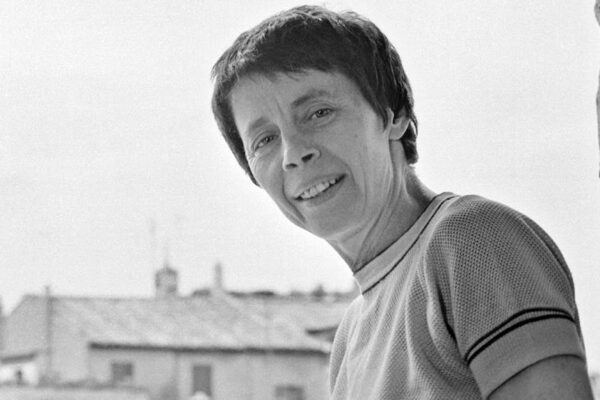

To know De Céspedes’s work is to understand both her politics and her capacity for prescience. The daughter of a Cuban diplomat father and Roman mother, she spent her early childhood abroad before returning to Italy as a teenager, where she was married off at the age of 15, divorced six years later. During World War II, she joined the resistance with her lover, an Italian diplomat, spending the latter years of the war on the run—first through the mountains of Abruzzo, and then in Southern Italy, where she became a resistance radio personality called Clorinda. Her broadcasts openly encouraged other women to take part in political activities. After the liberation, she founded and managed a literary magazine called Mercurio for several years and published novels to critical acclaim. She was widely read before her work fell into relative obscurity decades later. Her Side of The Story—published in Italy as Dalla Parte Di Lei—even spun off into a regular advice column in the magazine Epoca.

The author’s prescience finds its footing unapologetically in Her Side of The Story. In its 500+ pages, De Céspedes ultimately delivers compelling psychological portraiture, illustrating the complexities of the female condition and the types of suffering women are made to endure in a patriarchal society. Infused with Italian neo-realist drama, she volleys the narrative through different genres—diary, memoir, war drama, legal procedural, romance, allegory, multi-generational family story—throughout the three acts of the novel.

There is some masterful scene setting in part one, particularly around the apartment block where Alessandra grows up on Via Paolo Emilio in Prati, a modest, working-class Roman neighborhood. De Céspedes delivers descriptions of exceptional literary quality with the utility of an anthropologist—describing a bustling world “inhabited by women only” once the husbands leave for work, “an undisputed territory” anchored by the vivid imagery of gray rooms, balconies, spiral staircases and the building’s courtyard.

“…the women fled the dark rooms, the gray kitchens, the courtyard that, as darkness fell, awaited the inevitable death of another day of pointless youth.”

At the center of this world is Eleanora, Alessandra’s elegant, romantic mother, a concert pianist whose desire for liberation through her art—and ultimate inability to free herself from her circumstances—colors Alessandra’s consciousness. The two share a close bond, a “secret understanding.” But lurking in the shadows is Alessandra’s deeply unlikable father, sketched like a predator straight out of an animal planet documentary: “I felt he’d invaded our cozy, feminine world like an insidious enemy.”

A slower middle section, where Alessandra is forced to live with her paternal relatives in the countryside of Abruzzo, was originally cut from the first English translation of the novel. While it can feel like a detraction from the central narrative, readers can dig deeper to find a clear critique of fascism’s patriarchal ideals. The rural setting plays an important role: Mussolini’s regime was deeply invested in rural regions as part of a program of economic control of the agricultural sector, putting out a great deal of propaganda that glorified the agrarian lifestyle, much of it specifically geared toward women. On the family farm, the Corteggiani family attempts to impose those ideals onto Alessandra, pushing her into the duties of the household, farm work, and marriage, in spite of her open resistance and a desire to devote herself to her studies. Of particular note is Alessandra’s Nonna—the religious, fearsome, and respected head of the household—who unloads missives about the importance of sacrifice for the greater good and of giving up oneself.

All roads lead back to Rome in the dizzying final act, where Alessandra falls in love with an academic, antifascist agitator named Francesco Minelli, a man with a sense of justice, idealism, and political aspirations, a seemingly perfect contrast to her world of brute and disappointing male figures. She becomes deeply drawn to his charisma and inspired by his courageous political participation in the midst of the war, her thoughts clouded by grand, romantic delusions. Meanwhile, Francesco can barely reciprocate—or even register—Alessandra’s feelings. This all gives way to fast paced romantic drama that unfurls alongside sobering depictions of the last few years of World War II, where readers witness Alessandra unfurl, too.

In telling Her Side of the Story and bringing us down “the well” with Alessandra, De Céspedes masterfully chronicles how a lifetime of indignities and sufferings can pile up to fray even the most well-intended people. But more importantly, De Céspedes does the painstaking work of codifying, acknowledging, and defending the overlooked experiences of women of her time, a precursor to what would later become a zealous movement for women’s liberation in her country. Her Side of the Story is an achievement that warrants not only a second look at this forgotten writer, but also an important place in the canon of women’s literature.

Originally published in the Chicago Review of Books. Reposted by permission of the author and the publisher.

Image: Alba De Cespedes, Courtesy Mondadory