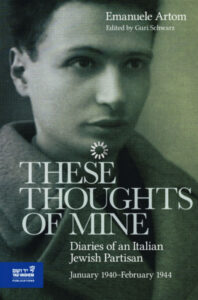

These Thoughts of Mine: Diaries of an Italian Jewish Partisan, January 1940–February 1944, edited by Guri Schwarz, Yad Vashem 2023

Guri Schwarz is associate professor of Contemporary History at the University of Genoa. He is co-editor of the e-journal Quest. Issues in Contemporary Jewish History as well as co-editor of the Routledge Studies in the Modern History of Italy series. He’s vice-director of the Centre for the History of Racism and Antiracism of the University of Genoa. He has held fellowships and visiting positions at the University of Bologna, the Luigi Einaudi Foundation, the University of Pisa, UCL, the Deutsches Historisches Institut (Rome), and UCLA.

He edited six volumes and is author of four books, including Emanuele Artom. These Thoughts of Mine. Diaries of an Italian Jewish Partisan, Jerusalem 2022; After Mussolini: Jewish Life and Jewish Memories in Post-Fascist Italy, (London-Portland, 2012); Tu mi devi seppellir. Riti funebri e culto nazionale alle origini della Repubblica, Turin, 2010; Attentato alla Sinagoga. Roma 9 ottobre 1982. Il conflitto israelo-palestinese e l’Italia (with A. Marzano), Rome, 2013.

Emanuele Artom (Aosta, 1915–Turin, 1944) was an Italian Jewish intellectual. He experienced Italian racial persecution and in 1943 joined the resistance, dying as a result of the atrocious torture he underwent at the hands of Fascist and Nazi tormentors in the spring of 1944. He is a well-known and revered figure among Italian Jews, and his memory endures also among non-Jewish Italians, especially—but not solely—in Turin, the city in which he grew up and spent most of his life. These diaries that he kept, now published for the first time in English, are an exceptional document of Italian Jewish life, a precious source for the study of Italian Judaism, of Fascist antisemitism, and of the anti-Fascist resistance. Nonetheless, with the exception of a restricted circle of scholars, his figure is certainly not well known outside of Italy. 1

Emanuele was the first child of Emilio Artom and Amalia Segre, 2 both of whom had earned degrees in mathematics and worked as high school teachers. He grew up in a family environment that was at once stimulating, loving, and in some ways also oppressive: although the parents bad extremely high expectations of both their children, Emilio Artom invested fervidly in his youngest son, Ennio (1920-1940), who was brought up to be a true wunderkind. 3

Emanuele was the first child of Emilio Artom and Amalia Segre, 2 both of whom had earned degrees in mathematics and worked as high school teachers. He grew up in a family environment that was at once stimulating, loving, and in some ways also oppressive: although the parents bad extremely high expectations of both their children, Emilio Artom invested fervidly in his youngest son, Ennio (1920-1940), who was brought up to be a true wunderkind. 3

After Ennio’s death in a mountain-hiking incident on July 29, 1940, Emanuele spent years trying to console his grief-stricken father. However, Emilio was overwhelmed by depression and could hardly see his eldest son, who was striving more than ever to obtain his approval. 4

Although his father did not seem to appreciate him as much as his younger brother, who was celebrated as a precocious genius, Emanuele was undoubtedly a brilliant young man. Studious and intelligent, with a heightened moral awareness, yet prone to brooding, Emanuele seemed to live not unlike Primo Levi, a few years his junior, and a classmate of his brother—”in a world inhabited by civilized Cartesian phantoms, by sincere male and bloodless female friendships.” 5

A historian of classical antiquity by training, Emanuele earned a degree from the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Milan in 1937 and cultivated a profound interest in literature and philosophy. Jewish history and culture were of great importance to him, even more so after the beginning of the Fascist antisemitic persecutions, when, together with his younger brother Ennio, he organized a Jewish study group at the Turin Jewish community library. A close-knit circle of young bourgeois Jewish boys and girls, with the occasional participation of some non-Jews as well, convened there twice weekly, attempting to find in the renewed and strengthened bonds of solidarity, as well as in their serious intellectual and cultural efforts, potential answers to the troubling questions that the regime raised concerning their identity as Italians and Jews.

Their approach to Jewish culture coincided with a search for dignity and a quest to elaborate a political conscience, developing into an implicit but clear anti-Fascist stance. Emanuele actively participated in the resistance since its inception in September 1943, playing an important role as political commissar for the Partito d’Azione 6 in the Waldensian 7 valleys’ in the vicinity of Turin. In the photographs that have survived, he appears scrawny and graceless.

In postwar testimonies we find a recurring insistence on Artorn’s lack of physical prowess, and particularly on his “frailty.” For example, his high school teacher and mentor, Augusto Monti, remembered him with affection as a “little haggard political commissar” and furthermore described his figure as “small, minute, frail.” 8 Massimo Ottolenghi, his friend and high school classmate, and later a partisan in the Val di Lanzo (Lanzo Valley), said that in school he was nicknamed “the little professor” because of his composure and “his physical frailty…he was thin, emaciated, his face devoured by his glasses. He did not join us for the physical education classes because he lacked the strength to climb a pole or a rope.” 9 In fact, on September 4, 1935, he would be judged unfit for military service due to thoracic insufficiency syndrome.” 10

Yet, however physically unsuited he was to the rigors of partisan life in the Alps, Emanuele did not shy away from participating in the struggle against Fascism. He joined the resistance with enthusiasm, he had a clear political conscience, and he acutely felt a responsibility to contribute, as much as he could, to the regeneration of a country corrupted by decades of Fascist dictatorship, materially and morally devastated by three years of war, and then lacerated by civil strife. Definitely not the warrior type and the most unlikely of heroes, his role as a political commissar entailed, among other things, ensuring the political preparation of the fighters; he strived to educate the young, sometimes illiterate, in most cases politically unaware members of his band.

The Afterword delves more deeply into Emanuele’s family background, his social milieu, and the trajectory of his personal life, placing him within the Italian and Turinese, Jewish and anti-Fascist, political and cultural scenario of his time. I do not wish to encumber the reader with a long and detailed historical and biographical account in this preface, choosing instead to allow the two diaries gathered here to speak first. They guide the reader into Emanuele’s private world; one page after another we witness the growth and the internal tribulations of a tormented young intellectual who faced, with a mixture of boldness and naivete, the challenges of a terrifying time. His personal notes are in many ways a unique and exceptional historical document. While there are several texts written by Italian Jews detailing the experience of persecution, and even more memoirs that were published after 1945 by former partisans—Jewish or not—we have very few unhampered personal documents of this nature.

Emanuele Artom died on April 7, 1944, as a result of the torture he was forced to endure at the hands of Italian and German guards, just over two weeks after he was captured by an Italian SS unit that was involved in attacking the partisan strongholds in the Val Infernotto (Infernotto Valley), Val Pellice (Pellice Valley), and Val Germanasca (Germanasca Valley) in the Piedmont region of northwest Italy. He was thus unable to “rework and fine-tune” his diary, “purifying it of the much useless content,” as he had intended.” 11 His private records miraculously survived his tragic demise, and they offer us not only a partial and yet invaluable window onto the musings of a young Jewish intellectual, but also glimpses into life in wartime Italy. We thus have before us a document that did not suffer from the bias of hindsight and that was not tainted as invariably happens—by the self-censorship characteristic of all memoirs. These factors, combined with the author’s staunch attention to detail, his heightened cognizance—deriving from his training as a historian—of the importance of scrupulously preserving records of events as they unfolded, his acute observations concerning the dynamics of the antisemitic persecutions, and later of the moral implications of the partisan struggle, make his diaries a precious and unique document. Emanuele does not simply describe events and people, this is not a mere chronicle of tragic moments; it is the written trace of an ongoing internal conversation in which the author continuously discusses with himself the political and ethical implications of the various choices he and others are facing. His inclination to introspection, his diffidence towards rhetoric as well as to lofty and dazzling ideologies, led him to a constant exercise in self-awareness and an unwavering critique of his own motivations and those of his companions. Perhaps even more so than many academic studies, his personal notes offer important insights into the atmosphere, the tensions, the hopes, and the torments endured by a generation of young Italians who were oppressed by the Fascist dictatorship, ravaged by the racial persecutions, and finally challenged to defiance by the collapse of the Italian State and the German occupation.

Two Diaries

This volume consists of two distinct diaries, not just one diary spanning the period 1940-1944. The shifting scenarios portrayed and the diverse contexts in which they were produced, as well as their postwar editorial history, all suggest that it is appropriate to separate and distinguish the two documents, referring to them as diaries in the plural. The personal notes gathered herein have thus been divided into two separate parts.

A first section, consisting of the diary that was kept from January 1, 1940, to September 10, 1943, is published here under the title “Personal Diary.” It contains noteworthy descriptions of the implementation of the racial laws in Turin and the effects of the Allied bombing raids, as well as traces of the process of intellectual growth that the young Emanuele experienced. He was forced to renounce his academic ambitions due to the regime’s antisemitic laws and had taken up a post as a teacher in the local Jewish school, but he did not abandon his intellectual v cation and was just starting to collaborate with the Einaudi publishing house. In this section we find several remarkable reading notes, which allow us to gauge the author’s voracious curiosity and his passion for literature and philosophy, covering works that range from Voltaire to Kant, from The Thousand and One Nights to Ariosto, from Dostoyevsky to Kafka, from D’Annunzio to Natalia Ginzburg. A dense and crucial portion is dedicated to Emanuele’s struggles with his Jewish identity and to his stance concerning Zionism, Toward the end of this first diary, we also find a careful analysis of the social and political processes that took place in the Piedmontese capital between the fall of Mussolini (July 25, 1943) and the onset of the Nazi occupation (September 10, 1943). This diary ends with Emanuele volunteering to join the ranks of the Partito d’Azione and wondering whether he will be able to reach the partisan bands.

The second diary—or “Partisan Diary”—offers information on. Emanuele’s life as a partisan (November 1943—February 23, 1944). After joining the Partito d’Azione on September 9, 1943, and enlisting as a volunteer, Emanuele left the family house i Moriondo—a town located 20 kilometers east of Turin to which the Artoms had relocated to escape the Allied bombing raids and moved to Val d’Angrogna, a small valley located roughly 50 kilometers southwest of Turin—its name derives from the river that flows through it, branching out north of the larger Val Pellice—where his father visited him on October 27, 1943. 12

On November 7, he joined the Giustizia e Liberta, (Justice and Liberty, GL) resistance bands in the Val Pellice, which were directly connected to the Partito d’Azione. He was immediately caught up in a delicate political affair: the exchange of representatives between rival resistance groups. Thus, Emanuele was sent to the Garibaldi (Communist) base at Barge, in the Val Infernotto (Infernotto Valley), to serve as a delegate of the Partito d’Azione in the Communist band lead by Pompeo Colajanni (a.k.a. Barbato). 13

This experiment in delegate exchanges (the Communists sent Dante Conte to Torre Pellice, where he stayed with the nascent Partito d’Azione formations) was decided upon around early October, during the course of one of the many meetings held in the home of the philosopher Ludovico Geymonat, a member of the Waldensian community and a Communist, with the intention of strengthening the working relationships between Azionisti (militants of the Partito d’Azione) and Communists. 14

As we learn from Emanuele himself, his stay with the Communist band was not easy and—in part due to the growing tensions between the two groups in January Emanuele returned to the Val Pellice, where he was appointed political commissar for the Partito d’Azione. At the end of the following month, he transferred to the Val Germanasca, to which some of the partisans from the Val Pellice were moving in an effort to extend their control to nearby areas. 15

The tone and content of the two diaries vary greatly, and they were in fact written in starkly different settings. The first diary is, to a significant degree, a young scholar’s notebook, interspersed with considerations regarding his personal and family life, and enriched with detailed depictions of the effects of the racial persecution and considerations resulting from the development of the war; politics emerges as a central theme only in its final pages, when—after the fall of Mussolini on July 25, 1943—the author not only finally feels free to express his anti-Fascist political inclinations but is also actively engaged in the activities of the Partito d’Azione.

By contrast, in the Partisan Diary, politics is the central issue. Here, references to literature are quite scarce—it was obviously difficult to procure books while fighting guerrilla warfare in the Alps—and centerstage are not printed words but rather the struggles of men and women living in dire conditions and risking their lives day by day. This particular document contains specific records of both the minor daily facts that made up a partisan’s life and descriptions of the major military turning points in the Val Infernotto, the Val Pellice, and the Val Germanasca, all mixed together with weighty ethical and political reflections on the meaning of the fight and the overarching goals that the resistance (and the Partito d’Azione in particular) should set for itself.

Emanuele is determined to depict men and events without embellishments, choosing from the outset to present the protagonists of the resistance with all their human flaws. The observations concerning the activity of the various groups with which he was involved are direct and outspoken, as are his considerations regarding the general political developments. He is often pessimistic as he registers the profound ignorance and the lack of political consciousness among the young boys who accounted for the bulk of the bands; at the same time, he appears determined to contribute as best as he can to their awakening, offering a touching testimony concerning his faith in the value of education.

Publication History: From the Original Manuscript to the Final Unabridged Edition

To complete these introductory pages, it is necessary to tell the story of how Emanuele’s personal notes survived and reached us today, as well as their publication history. It is a story of stubborn determination, sheer luck, and intelligent foresight. It is also, to a large degree, a story interspersed with tears and pain, the agony of a grieving mother who found some respite from her misery in the efforts to preserve the memory of her murdered son. Finally, the vicissitudes of Emanuele’s diaries in the postwar period, their publication and reception, shed light on the shifting space and place for Jewish memories within the dominant Italian national narrative.

Emanuele Artom was well aware that the pages he was writing during his life as a partisan were compromising; furthermore, he knew that he needed to travel light and could not burden himself with a growing mass of papers. As he gradually composed his Partisan Diary—written variously in pen and at times in pencil on whatever scraps of paper came to hand—Emanuele handed over its pages for safekeeping to people he trusted: one part was delivered to Paola Nizza Levi, a friend of the Artom family who contributed directly to the partisan struggle and whose son, Ruggero (Geo), collaborated closely with Emanuele in the resistance; 16 another portion of the diary was entrusted to Clementina Poet—a Waldensian schoolteacher who bad hosted him many times in her home in Torre Pellice; while the very first pages of the diary were kept by Emanuele’s close friend and fellow partisan, Giorgio Segre. 17

These pages survived their author, and, after the war, his mother, Amalia Segre Artom, patiently managed to piece them together. Emanuele certainly wrote more, in fact there are long interruptions suggesting that portions of his diaries were lost or destroyed. In one instance the author mentions “burned pages,” suggesting that—for some reason—he destroyed his own notes. 18 We have no diaristic trace of the last month of his partisan activity. Indeed, the pages he most likely wrote in the period from February 24 to March 25, 1944, the day of his arrest, were never found; presumably they were destroyed or lost by whoever received them for safekeeping, or else, perhaps, eliminated by the diarist himself during the roundup in which he was captured. In any case, a significant part of hi- diaristic entries survived. The text of the Partisan Diary reproduced here is the fruit of a philological reconstruction based on the handwritten manuscript currently preserved in the archives of the Fondazione Centro di Documentazione Ebraica Contemporanea (CDEC) in Milan.

The story of the first part of the text, Emanuele’s Personal Diary, covering the period 1940-1943, is quite different. Despite extensive efforts expended in numerous directions, it has proved impossible to locate the original manuscript, which appears to have been lost. It was thus necessary to rely on the edition published by the CDEC in 1966, edited by Paola De Benedetti and Eloisa Ravenna with the assistance of Emanuele’s mother, 19 which in turn reproduced the text published in the 1954 volume edited by Benvenuta Treves—a close friend of the Artom family—entitled Tre vite; dall’ultimo ‘800 alla meta del ‘900. Studi e memorie di Emilio, Emanuele, Ennio Artom (Three Lives: From the Late Nineteenth Century to the Mid-Twentieth Century. Studies and Memoirs of Emilio, Emanuele, Ennio Artom,), which contained excerpts from Emanuele’s diaries as well as from those of his father Emilio and his brother Ennio. 20 There are only two discrepancies between the 1954 and 1966 editions of the Personal Diary: two passages were added to the 1966 edition; in all likelihood based on materials supplied by Emanuele’s mother, who must have been in possession of the original manuscript or a copy of it. 21

However, the differences between the two editions (1954 and 1966) of the Partisan Diary are much greater; in fact only a limited number of pages concerning the partisan period were published in 1954. Furthermore, as we shall see below, several sections of the Partisan Diary were also omitted from the more extensive 1966 edition.

Amalia Segre Artom played a key role in the publication of these diaries. By April 1948 she had gathered her son’s notes and sent a typescript copy for preservation to the Istituto Piemontese per la Storia della Resistenza (Piedmontese institute for the History of the Resistance). The director of the institute, Giorgio Vaccarino, dispatched a letter thanking her, expounding on the value of the document, one that—he stated—was “well above any other” received by the institute up to that point. He suggested that, with her agreement and in collaboration with her, he would try to see some sections published, excluding those pages containing information of a more private nature. 22 As far as it is possible to ascertain, this did not come to pass, and in July 1953 Amalia Segre Artom wrote to Vaccarino demanding that the Partisan Diary be returned to her. 23 She may have been motivated to do so by that fact that Benvenuta Treves was then engaged in preparing the aforementioned book containing portions of the diaries kept by Emanuele, his brother Ennio, and his father Emilio.

The father, Emilio, had suffered a stroke on February 17, 1944. He survived but remained impaired by a right hemiparesis. After his death, on December 11, 1952, his wife redoubled her efforts to preserve and honor his memory and that of their two children. As she wrote in a letter to the journalist and translator Anita Rho, this became her “only goal” in life. 24

She continued to work as headmistress of the Turin Jewish school, which in 1946 was renamed after her son Emanuele, 25 but her papers reveal how she closely monitored publications mentioning her deceased family members and actively contributed to ensuring that books dedicated to them would see the light. The first major result of her endeavors was the publication of the 1954 volume edited by Treves, which contained several pages from Emanuele’s Personal Diary, from the period 1940-1943, as well as a segment of his Partisan Diary. 26

Two years later, a book celebrating the intellectual and moral qualities of her youngest son, Ennio, was also published. 27 Amalia Segre Artom did not limit herself to promoting the production of those books but also strived to ensure that the virtues of her loved ones, and especially Emanuele’s political role in the resistance, would obtain visibility, sending copies of the book edited by Treves to several public figures (intellectuals, journalists, politicians) and to various periodicals. Her relentless dedication produced some significant results, and the book was well received and widely reviewed. Yet this was not enough: numerous pages of the Partisan Diary were omitted from the Treves volume probably to maintain some equilibrium between the section dedicated to Emanuele and those that reproduced the diaries of his father and brother. Amalia Segre Artom was aware of the special value of the Partisan Diary, and the reviews received by the 1954 volume must only have strengthened her resolve to see it published in full. 28

In the early 1960s, she lived only to preserve the memory of her husband and sons; as she noted, that was “the only thing that allowed her to endure life.” Using those words, in 1963 she addressed Ferruccio Parri, who had been one of the leaders of the Partito d’Azione, a key figure in the resistance, and subsequently served as the first president of the Council of Ministers of Italy after liberation, begging him to lend his support to a new and complete edition of the Partisan Diary. In that letter, she specified that significant sections of that text had been omitted from the 1954 edition, following the advice of Giorgio Vaccarino, who had suggested that “those parts that did not put [the resistance] in a good light” should be removed. However, she added that she now believed the time was right for it to be published in its entirety, and she asked for Parri’s advice on the matter. She also requested his opinion on what to do concerning the identification of the various figures with whom Emanuele interacted during his five months as partisan, wondering whether it was appropriate to spell out and publicly reveal the identities of those referred to in the original manuscript—and in the Treves edition—only with initials. She included with her letter a copy of the transcription of the Partisan Diary, specifically indicating which passages had been omitted from the 1954 edition. 29

Parri was not a close friend of the family, but his dedication to preserving the memory of the resistance was well known. Furthermore, he was aware of Emanuele’s contribution to the struggle and his tragic fate, and for that reason he had been in contact with the Artoms since the early postwar years. 30 In seeking his help, Amalia Segre Artom was not merely looking for advice concerning editorial decisions but rather sought symbolic recognition, aiming to secure her son a place in the national pantheon of the heroes and martyrs of the Republic born from the resistance. In 1949, Parri had in fact played a key role in the creation of the Istituto Nazionale per la Storia del Movimento di Liberazione in Italia (National Institute for the History of the Liberation Movement in Italy), which became the center of a network of local institutes dedicated to the history of the resistance. It is plausible that Amalia Segre Artom hoped that the diary could be published by the Istituto Nazionale. 31 That would have been extremely gratifying since it would have implied recognition by the official custodians of the memory of the anti-Fascist struggle, raising her son’s testimony to national prominence. No trace has been found of Parri’s reply, and the subsequent developments suggest that this route proved to be impracticable.

In fact, in 1964 the CDEC in Milan started working on a new edition of the diaries, in close contact with Amalia Segre Artom, 32 and, two years later, in 1966, a more extensive—although still not integral edition of the Partisan Diary was published directly by that small institution devoted to the preservation of Italian Jewish history. Through the publication in a first limited and partial form in the volume entitled Tre vine, edited by Benvenuta Treves for the Jewish publishing house, Israel, in 1954, and then via the more complete version published by the CDEC in 1966, Emanuele’s diaries circulated in Italian political and cultural circles. However, they were framed as specifically Jewish testimonies, placed in a peculiar niche, connected to and at the same time separate and distinct from the dominant national narratives concerning the resistance. This is made evident not only by the fact that they were produced by Jewish publishers, but also by the graphic choices made for the book covers: in both cases a Magen David appears prominently.

In any case, the 1966 volume represented a significant improvement compared to the 1954 publication: Emanuele’s diaries finally stood alone, the texts were enriched with many pages that had been omitted from the previous edition, and by an introduction and an apparatus of footnotes that provided some necessary contextualization and identified the names of some of the figures mentioned,

Notwithstanding Amalia Segre Artom’s intention to publish the Partisan Diary in full, a number of sections of the original manuscript were omitted. In particular, Eloisa Ravenna and Paola Debenedetti the editors, who worked in close cooperation with Emanuele’s mother expunged passages concerning Emanuele’s personal life, excerpts related to his struggles with his Jewish identity and religious observance, sections referring to the sphere of sexuality in the partisan bands, and also phrases and paragraphs that illustrated, in sometimes harsh tones, the tensions and rivalries within the GL partisan bands in the Val Pellice as well as the conflicts between the Communist Garibaldi brigades and the GL units connected to the Partito d’Azione. Such editorial decisions were not uncommon in early editions of resistance documents.

As Giovanni De Luna pointed out, modesty and censorship weighed heavily on the construction of the memory of the Italian resistance. In the context of the Cold War, and in a general political climate that saw the resistance experience become the target of repeated attacks, the efforts of the former partisans to preserve the history of their struggles was very often characterized by a markedly defensive attitude, reflected in the tendency “to insist solely on the ‘edifying’ aspects of the resistance.” 33 In this atmosphere, the inclination to avoid revealing the internal tensions that characterized the liberation movement, the desire to conceal the inevitable uncertainties and contradictions that marked even the souls of the hardiest and most determined anti-Fascists, and finally the deeply rooted idea that the private sphere of the former partisans had to be preserved and separated from their public (and political) commitment were all factors that could hardly fail to exert an influence on the agenda of a very small documentation center such as the CDEC.

The CDEC was founded in 1955 at the behest of a group of young Italian Jews members of the Federazione Giovanile Ebraica d’Italia (Jewish Youth Federation of Italy, FGEI) with close ties to the Italian Communist Party who intended that the institute would reconstruct the Jewish contribution to the Italian resistance and, at the same time, write a history of the racial persecutions. In the early 1950s, the leaders of the FGEI went so far as to claim that there existed an “indissoluble bond between Judaism and anti-Fascism.” 34

Thus formulated, the issue was indubitably misframed: there was no such thing as “Jewish anti-Fascism,” though there had been many anti-Fascist Jews—just as there had been also many Fascist Jews with strong convictions. 35 In creating the CDEC, that young generation of Italian Jews was driven by the determination to fit collectively—as Jews—into the anti-Fascist patriotic narrative, an effort that reflected their need to obtain full political and cultural reintegration. By the early 1960s, the CDEC had evolved somewhat since its early beginnings, yet an emphasis on the celebration of the Jewish contribution to the resistance persisted when work commenced on the edition of the diaries. Emanuele Artom, who had been awarded the Silver Medal for Military Valor, was perceived as a Jewish hero and a martyr of the resistance, and his sacrifice could be seen as a symbol of the Jewish minority’s active contribution to the rebirth and the regeneration of the country. The effort invested in the preservation of his memory thus accorded with the agenda of the CDEC. 36

The 1966 edition—which was, at the time, one of the most significant products of the CDEC’s activity 37 —had the unquestioned merit of making Emanuele’s account available, presenting it in an understated manner that proved to be effective. It included both diaries, gathered and presented here as the Personal Diary, for the period 1940-1943, and the Partisan Diary, covering the period from November 1943 to the end of February 1944. Although elements that at the time were deemed disturbing and today appear extremely interesting—were omitted, the Partisan Diary still emerged as an extraordinary document. That short book, published independently by the CDEC in a limited print run, resonated considerably at the time, also outside the Jewish milieu, obtaining important reviews by well-known and authoritative anti-Fascist intellectuals. 38 It continued to circulate for decades, once it was out of print, in Xerox copies that friends and scholars passed from hand to hand. 39

Interest in Emanuele Artom and his diaries made a major comeback decades later, in the early 1990s, in the framework of renewed scholarly attention and intense political debate concerning the resistance. 40 Claudio Pavone, in his groundbreaking 1991 book dedicated to the issue of morality in the resistance, repeatedly quoted passages from Emanuele’s diaries; in fact, it was one of the most cited sources in his book. Pavone caused Italian historiography on the resistance to switch gears, moving from the study of the major political organizations that promoted the anti-Fascist insurgence to the study of the partisans’ subjectivity, and to a lesser degree also that of the Fascists; from that perspective, Emanuele Artom’s diary constituted an invaluable resource. 41 Two years following the publication of Pavone’s book about the Italian Civil War, a scholarly conference was dedicated to Emanuele Artom, and this later resulted in the publication of a volume edited by Alberto Cavaglion for the Istituto Storico della Resistenza del Piemonte. 42 Several years later, in 2005, Cavaglion insisted once again on the historical relevance of Emanuele’s testimony in the pamphlet La Resistenza spiegata a mia figlia (The Resistance Explained to My Daughter). 43 Nonetheless, the diaries had long gone out of print; indeed, the 1966 volume was a genuinely rare book, coveted by collectors.

The time was ripe to republish Emanuele’s diaries, awarding them the relevance they deserved. At the end of 2004, the CDEC entrusted me with the task of editing the diaries, so I worked on reproducing the original manuscript in its entirety, while preparing an apparatus of footnotes and explanatory references that would offer necessary contextualization and adequately reflect the evolution of historiography. Interest in Emanuele’s diary was growing well beyond the usual Italian Jewish and local Turinese circles; thus, the prestigious publishing house Bollati Boringhieri, the same publisher of Pavone’s book as well as several other key texts of a new wave of scholarship on the civil war and German occupation, expressed its willingness to invest in the publication. A new and unabridged edition was finally published in 2008. 44

Since then, attention and interest in Emanuele Artom’s figure has grown further. In Turin, starting in 2011, the Community of Sant’Egidio an influential lay Catholic association founded in 1968—has organized, together with the local Jewish community, an annual “Emanuele Artom March”; the event takes place in the last week of March—the period in which Emanuele was arrested.

The route of the procession passes through the streets of the city connecting the Porta Nuova train station, from where convoys left for the concentration camps, to the synagogue in Piazzetta Primo Levi. The explicit aim of this initiative is to promote the memory of racial persecutions as part of the battle against modern-day xenophobia. In this instance, Emanuele is celebrated more as a symbol of the persecuted minority and a victim of the Nazis than as a political militant and a partisan fighter. Furthermore, two documentaries dedicated to him have been produced, one in 2011 and another one in 2014. 45 A novel, connecting his final years to life in Turin today, was also published in 2016. 46 In the same year, in Turin, and with the support of the municipal administration, the artists Andrea Gritti and Margherita Bobini created a mural painting with Emanuele’s face and a phrase taken from his Partisan Diary on the very street that had been named after him. 47 In 2017, a music and arts festival entitled Avevamo 20 anni: Artisti per Artom (We Were Twenty Years Old: Artists for Artom) was held in Turin on June 27-29, 2019. It featured live music, readings from Emanuele’s diaries, roundtable discussions, and the screening of the 2011 documentary dedicated to him; it was organized with the support of the Regional Council of Piedmont and the Comitato Resistenza e Costituzione (Resistance and Constitution Committee) 48 . In 2021, a novel for young adults, extolling the virtues of partisan fighters, specifically depicting the activities of one of the bands in which Emanuele was active, was published, with Emanuele as one of the key characters. 49 Yet the most noteworthy public recognition came with the Liberation Day (April 25) ceremony of 2021, when the president of the Council of Ministers, Mario Draghi, explicitly referenced Emanuele Artom in a poignant speech that did not merely celebrate the values of the resistance, but reminded the country of its own historical responsibilities and condemned political apathy as immoral. 50

This English language edition is a significantly revised version of the 2008 Italian edition. It was of course necessary to amend some imprecisions, to take into account the relevant scholarship that has appeared over the years, and to add new explanatory footnotes to make the text accessible to a foreign public that might not be well acquainted with the Italian political and cultural context of the time. Furthermore, I felt the need to rewrite the Preface and significantly revise the Afterward, introducing some new elements or discussing in depth some issues that the Italian edition mentioned only in passing. Regarding the critical apparatus, I opted according with decisions made in the Italian edition—for a commentary that allows the reader to identify places, people, and episodes, cross-referencing the information presented by Emanuele with other documents and accounts from the period: the anti-Fascist press, other diaries and memoirs, as well as archival sources. The most complicated and time-consuming aspect of the research conducted in preparing the 2008 Italian edition regarded the identification of the people mentioned in the diaries. Often Emanuele used only initials, and in the Partisan Diary he usually refers to other partisans by their nom de guerre (at times using only the first letter of the pseudonym adopted when they entered the resistance). Beyond the usual cross-referencing with other traditional sources, the online database of the partisans in Piedmont has been a precious source of information.” In preparing this English edition, I have been able to identify a few more names. However, some figures still elude recognition, and it is important to point out that some identifications remain only tentative.

Whenever it has been possible to identify them, the names of people and places have been included in square brackets. Likewise, the surnames of people identified only by their first names or by a pseudonym or nom de guerre are also spelled out in square brackets, where this was judged necessary. Abbreviated words are written out in full or the convenience of readers.

Footnotes

1 Tablet Magazine presented Artom's figure to an English-speaking audience, underscoring the value of his diaries, see S. Libby, "The Diary ofthe Italian Resistance," Tablet Magazine, December 1, 2017, littps://www.tabletrnag.comijewish-life-and-religion/248734/diaryof-the-italian-resistance (last accessed December 10, 2019). Emanuele Artom and his diaries are typically mentioned in English-language scholarship by authors who dedicate their attention to other figures or broader issues, such as Primo Levi and his Turinese milieu, the history and memory of the resistance, or modern Italian Jewish history. The entry on Partisans written by I. Guttman for the Encyclopedia Judaica, vol. 15, 2nd ed. (2007), mentions him as well as two other Italian resistance fighters, but it incorrectly places him in the Val di Piana (Tuscany), possibly confusing him with another Jewish anti-Fascist, Eugenio Artom. In the same encyclopedia, the entry Artom (vol. 2) mentions his name and his scholarly and political activity while briefly presenting the history of this Italian Jewish family. 2 On Emilio Artom, see Personal Diary, March 22, 1941, footnote 9; on Amalia Segre, see Personal Diary, September 3, 1941, footnote 29. For further information on both and the family in general, see the Afterward, pp. 225-232. 3 Regarding Ennio Artom, see Personal Diary, December 29, 1940, footnote 4. 4 The father's inconsolable anguish, his tendency to perceive his eldest son as inadequate and not on the same levcl as Ennio, the youngest, who died prematurely, emerges clearly in his diaries. See the diaries of Emilio Artom published in 13. Treves, ed., Tre dall'ultimo '800 alla meta del '900: Studi e memorie di Emilio, Emanuele, Ennio Artom (Florence: Casa Editrice Israel, 1954), for example pp. 74, 78, 82, 94, 100, 103, 112, 113. 5 P. Levi, If This Is a Man, in Primo Levi, The Complete Works of Primo Levi (New York and London: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2015), vol. 1, p. 1. The phrase appears in the opening lines of the second edition of Levi's book (1958) and was used by the author to describe his life in the period from the beginning of the racial persecution to his arrest and subsequent deportation. 6 An anti-Fascist political movement founded in July 1942. For more details see Personal Diary, July 30, 1943, footnote 88. 7 The Waldensian movement is a Proto-Protestant Christian religious group. ft was founded by Peter Waldo in Lyon in the twelfth century and later spread in the Alpine regions of France and Italy. In Italy, the Waldensian community is concentrated mainly in Piedmont, especially in the Val Pellice (Pellice Valley), the Val Germanasca (Germanasca Valley), and the Val Chisone (Chisone Valley). 8 A. Monti, "Tre vite," 'Unita, May 25, 1954 9 See the video testimony given by Ottolenghi to Luciano Boccalatte on April 21, 2005:http:1/www.metarchivi.itidett_documento.asp?id-30638ztipo=VIDEO (last accessed April 1, 2021). For another example, see A. Segre, Memoirs of Jewish Life: From Italy to Jerusalem, 1918-1960 (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), P. 273. 10 The document certifying his inadequacy for military training can be found in Archive of the Foundazione Centro di Documentazione Ehraica Contemporanea (CDEC Archive), Emanuele Artom collection, B. 1, F. 8. 11 See Partisan Diary, November 23, 1943. 12 See the account of the visit as described in the father’s diary in Treves, Tre vite, pp. 122-123 13 See Partisan Diary, November 23,1943, footnote 9. 14 The following took part in those meetings on behalf of the Partito d'Azione: Mario Aiidreis, Arialdo Banfi, Roberto Malan, Carlo Mussa Ivaldi, and Franco Venturi, while the Communists were represented by Gustavo Comollo, Dante Conte, Ludovico Geymonat, Antonio Giolitti, and Giancarlo Pajetta. See D. Gay Rochat, La Resistenza nelle Valli valdesi, 3rd edition (Turin: Claudiana, 2006), pp. 53-54; G. De Luna, La Resistenza peifetta (Milan: Feltrinelli, 2015), pp. 58-59. 15 See Gay Rochat, La Resistenza nelle Valli, pp. 59ff. 16 On Paola Nizza Levi and her son Ruggero (Geo), see Partisan Diary, February 4, 1944, footnote 178 17 Concerning Giorgio Segre, see Personal Diary, September 3, 1941, footnote 36. 18 See Partisan Diary, February 18, 1944. 19 E. Artom, Diari: Gennaio 1940—febbraio 1944 (Milan: Fondazione Centro di Documentazione Ebraica Contemporanea, 1966). Concerning the origin of that publication, see the account by Paola De Benedetti in A. Cavaglion, ed., La moralita armata: Studi su Emanuele Artom (1915-1944) (Milan: Angeli, 1993), pp. 79-87. 20 Treves, Tre vite. Benvenuta Treves (1885-1973) was a high school literature teacher and anti-Fascist with ties to the Socialist Party. 21 The additions concern the entire diary entry for August 9, 1943, and the first paragraph of the entry for September 9, 1943. 22 Letter by Giorgio Vaccarino to Amalia Segre Artorn, April 19, 1948, CDEC Archive, EmanueleArtom Collection, b. 1, 1. 1. Giorgio Vaccarino (1916-2010) was a partisan with the GL bands and a representative of the Partito d'Azione in the Comitato di Liberazione Nazionale (National Liberation Committee) in Piedmont, He subsequently dedicated himself to the history of the resistance and was the first director of the Istituto per la Storia della Resistenza in Piedmont, founded in 1947. On the history of that institute, see G. De Luna, "Tre generazioni di storici: L'Istituto storico della Resistenza in Piemonte," Italia contemporanea, 172 (1988), pp. 53-77. 23 Amalia Segre Artom asked Giorgio Vaccarino to return the typescript to her in a letter. dated July 13, 1953. Portions of the diary can still be found among Vaccarino's papers: a) a typewritten copy of the first part of the diary, entitled "Dai diari di Emanuele Artom" (consisting of eight pages, dated July 28 to September 10, 1943) and b) forty-five pages bearing the title "Pagine di diario di vita partigiana scritte dal dottor Emanuele Artom" (from November 23 to February 23, 1944). See Archivio dell'Istituto Piemontese per la Storia della Resistenza e della Society Contemporanea "Giorgio Agosti" (Archivio Istoreto), C 60 a. 24 Letter from Amalia Segre Artom to Anita Rho, March 12, 1962, CDEC Archive, Emanuele Artom Collection, b. 1, f. 1.. The letter was written to Anita Rho because she was the niece of the famed anti-Fascist Barbara Allason. Amalia Segre Artom asked Rho to convey to her aunt some remarks concerning her memoir, in which she mentioned Emanuele and Emilio with some inaccuracies. The memoir was the well-known Memorie di un'antifascista, which was published for the first time in 1947 by Edizioni U. and then reprinted in 1961 (Avanti, Milano). Amalia Segre Artom read the 1961 edition. 25 See the letter by Chief Rabbi of Turin Dario Disegni to Emilio and Amalia Segre Artom (October 20, 1946), in which he informed them that the Jewish school was to be renamed "Scuola Ebraica Emanuele Artom." 26 Treves, Tre vile. Two pages, with excerpts from the diary entrie. for September 9, November 30, and December 10, were republished shortly thereafter in Torino: Rivista mensile municipale, 4 (1955), pp. 153-154. 27 M. Ottolenghi Minerbi, Ninìn bimbo felice (Padua: Amicucci, 1956). The book concentrates on his childhood years, also reproducing some portions of his childhood diaries. 28 Ample evidence of the efforts made by Amalia Segre Artom for the circulation of that book, with copies of the reviews published in a wide array of periodicals, both Jewish and non-Jewish, can be found in the CDEC Archive, Artom Collection, B. 3 F. 29. Among the most notable contributions see the essay by L. Bulferetti, "Risorgimento e Resistenza: Making Italian Jews," 1l Movimento di Liberazione in Italia, 34-35 (1955), pp. 44-55 (this is the text of a lecture delivered at the II Convegno di Studi sully. Storia del Movimento di Liberazione, entitled "La crisi italiana del 1943 e gli inizi della Resistenza," Milan, December 5, 1954); and the review by Piero Pieri, I1 Ponte, 1 (1955), pp. 246-248. 29 Letter from Amalia Segre Artom to Ferruccio Path, September 16, 1963, CDEC Archive, Artom Collection, B. 3. F. 29. 30 Letter from Ferruccio Parri to Emilio Artom, December 6, 1945, in which the then president of the Council of Ministers wrote that he had heard of Emanuele's tragic end, celebrated him as a "martyr and a hero," and swore that "the memory of his sacrifice would remain forever alive in our hearts." CDEC Archive, Artom Collection, B. 1 F. 6. Later Parri also intervened, at the request of Arnalia Segre Artom, in the process that led to Emanuele being posthumously awarded a military rank for his service as a partisan. See CDEC Archive, Artom Collection, B. I F. 1. Regarding Parri, see the biography by Luca Polese Remaggi, La nazione perduta: Ferruccio Parri nel Novecento itailano (Bologna: Il Mulino, 2004). 31 On the folder containing the original manuscript of the Partisan Diary, now in the CDEC Archive, are a few lines written by hand by Amalia Segre Artom: "On my death this file is to be handed over to I4 Movimento di Liberazione in Italia." She clearly meant the Istituto Nazionale per la Storia del Movimento di Liberazione, as is confirmed by the address that also appears on the cover. This was subsequently crossed out with repeated lines but is still clearly legible. In its place, a different destination for the diaries was noted: the "Centro di Documentazione Ebraica Contemporanea." See CDEC Archive, Artom collection, B. 1, F. 9. For an overview of the process that led to the creation of the Istituto Nazionale and, more generally, of the context in which the conservation of documents and the history of the resistance developed in the postwar period, see G. Zazzara, La storia a sinistra: Ricerca e impegno politico dopo il fascismo (Rome-Bari: Laterza, 2011), pp. 72-92; for the history of the Istituto Nazionale, see also G. Grassi, ed., Resistenza e storia Quarani 'anni di vita deli nazionale e degli istituti associati, 1949-1989 (Milan: Angeli, 1993); E. Collotti, e la rete degli istituti associati: Cinquant'anni di vita," Italia contemporanea, 219 (2000), pp. 181-191. 32 L. Picciotto Fargion, "Eloisa e it CDEC," La Rassegna mensile di Israel, 1-2-3 (1983), pp. 20-21. 33 G. De Luna, "La Resistenza tra storia e rnemoria," introduction to G. Agosti and D. L. Bianco, Un'amicizia partigiana: Lettere 1943-1945 (Turin: Bollati Boringhieri, 2007), p. li. Concerning the public memory of the resistance and its various phases, see F. Focardi, La Guerra della memoria: La Resistenza net dibattito politico Italian° dal 1945 ad oggi (Rome-Bari: Laterza, 2005); P. Cooke, The Legacy of the Italian Resistance (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2011). 34 See the resolutions approved at the FGEI congress held in December 1953 and published in the weekly Israel, December 31, 1953; and the article "Fondamenti programmatici per l'avvenire della Federazione Giovanile," Israel, February 10,1954. 35 Nero Treves provided a clear-eyed overview of the problem in an article entitled "Antifascisti ebrei o antifascismo ebraico?" La Rassegna mensile di Israel, 6 (1981), pp. 32-58, now in P. Treves, Scritti novecenteschi (Bologna: Il Mulino, 2006), pp. 119-130. 36 On the dynamics of postwar reintegration allow me to refer the reader to my own book, Guri Schwarz, After Mussolini: Jewish Life and Jewish Memories in Post-Fascist Italy (London and Portland: Vallentine Mitchell, 2012); in particular, concerning the FGEI and the origins of the CDEC, see pp. 83-91 and 159-161. 37 Three booklets were previously published by the CDEC, edited by G. Valabrega, entitled Gil ebrei in Italia durante it fascismo, the first of which appeared as Quaderno della FGEI (Milan, 1961) while the latter two were entitled Quaderno del CDEC 1962-1963). Concerning the CDEC, see the annotations by L. Picciotto Fargion, “La ricerca del Centro di documentazione ebraica contemporanea sugli ebrei deportati dall'Italia," in P. Mornigliano Levi, ed., Storia e memoria delta deportazione: Modelli di ricerca e comunicazione in Italia e in Francia (Florence: La Giuntina, 1996), pp. 60— 72, See also Pieciotto Fargion, "Eloisa e i1CDEC"; M. Sarfatti, "La Fondazione Centro di Documentazione Ebraica Contemporanea," in Sarfatti, ed,, Funzioni dei centri i storia e cultura ebraica nella società contemporanea (Milan: Proedi, 1998), pp. 45-50 38 Among the many reviews, see in particular the one authored by N. Bobbio, "La moralità armata,” Il sedicesimo: Bollettino bibliografico trimestrale della Casa Editrice La Nuova Italia, 6 (1966), p. 15; and the one written by E. Passerin D'Entreves, Rivista di scoria e letteratura religiose, 2 (1967), pp. 349-350. 39 Philip Cooke observed that Emanuele's diary was the "most notable work" among the memoirs and diaries that appeared in the 1960s (following the first major wave of diaries and memoirs published in the immediate postwar years) and also remarks that it would become "something of a cult text in his native city of Turin." See Cooke, The Legacy, p. 96. 40 See Focardi, La Guerra della rnemoria, pp. 60ff; Cooke, The Legacy, pp. 149ff. 41 C. Pavone, A Civil War: A History of the Italian Resistance (London and New York: Verso 2013). The work was first published in Italian in 1991. On the relevance of the references to Emanuele in Pavone's book, see Cooke, The Legacy, p. 161. For a discussion of the nature and relevance of Pavone's cultural operation, see Guri Schwarz, "The Moral Conundrums of the Historian: Claudio Pavone's A Civil War and Its Legacy," Modern Italy, 4 (2015), pp. 427-437. 42 Cavaglion, La moralità armata. 43 A. Cavaglion, La Resistenza spiegata a Inia figlia (Naples: L'ancora del Mediterraneo, 2005), pp. 69fr. 44 E. Artom, Diari 1417 partigiano ebreo: Gennaio 1940—febbraio 1944 (Turin: Bollati Boringhieri, 2008). With respect to the 1966 CDEC edition, I restored the sections that were omitted and corrected a few errors in transcription, while the footnote apparatus was completely rewritten. 45 Emanuele Artom, it ragazzo di via Sacchi, directed by Francesco Momberti, produced by Associazione Culturale Pianoerre, 2011; La Resistenza Ira scelta e martirio, directed by Enrico Cerasuolo, produced by Rai Storia with Zenit Arti Audiovisive, 2014. 46 Alessandro Musto, Via Artom (Rome: RaiEri, 2016). 47 The artwork is situated at the corner between Artom, and Candiolo streets. See http://www.museotorino.itiviewis/778f57bd12ed48199c771d5a133f799b and https://www, museotorino.it/viewis/48259f71b9f64ff9b165a2274d5eecbf (last accessed December 10, 2019). The phrase reproduced on the wall is taken from the Partisan Diary, January 26, 1944: "Fascism isn't just a roof tile that fell on our heads by accident...If we don't develop a political consciousness, we won't know how to govern ourselves, and a people that doesn't know how to govern itself necessarily falls under foreign domination or else under the dictatorship of one of its own." 48 Festival program:http://www.cr.piemonteitiwebifilesi Avevamo20anni---Programma.pdf (last accessed December 10, 2019). On that occasion the Bollati-Boringhieri publishing house reprinted the 2008 edition of the diaries. 49 Marco Ponti and Christian Hill, R: Ribelli, Resistenza Rock and Roll (Milan: Feltrinelli, 2021). 50 Speaking in Rome at the Museo Storico della Liberazione (Historical Museum of the Liberation), created in the former jails where Jews and anti-Fascists were held and tortured by German occupation forces, President Draghi referenced only two individuals: Auschwitz survivor and Senator for Life Liliana Segre and Emanuele Artom. Draghi said: "In honoring the memories of those who fought for freedom we must remember that we weren't all, us Italians, 'good people.' We must remember that not taking sides is immoral, to use the words of Artom. It means murdering, once more, those who showed courage in the face of the occupiers and their allies and sacrificed themselves to allow us to live in a democratic country." He was probably referencing what Artom wrote in the diary entry for January 26, 1944: "Fascism isn't just a roof tile that fell on our heads by accident; it's an effect of the political apathy and therefore of the civil immorality of the Italian people."