Traditional Jewish Music and Italian-Jewish Liturgical Traditions

Jerusalem, summer 1955, Published in: “Rassegna Mensile di Israel”, Tishri 5718, Ottobre 1957, Vol. XXIII, N. 10

Translated by Inga Pierson

What is the status of the minhaghim with regard to liturgical music and its distribution in Jewish Italy today? The goal of this paper is, first and foremost, to report on my findings in contemporary Italy. Then, in order to better contextualize my research, I will also go back and trace the history of these musical traditions from the Middle Ages. It is a difficult task but perhaps not an impossible one.

There are seven different types of “ritual” in Italy today:

1) The oldest is of course the Roman-Italian, even though in the Rome of today, Sephardic influences prevail in the rite practiced in the Central Synagogue. It is well known that the five “Scole” – Sicilian, Catalan, Castilian, Italian and “Scola-Tempio” – were supplanted, about fifty years ago by the central synagogue. There, the Italian rite has generally prevailed although certain customs and especially the music tied to the Iberian rite seem to have triumphed over the original Italian, or minhag bené-Romi. For example, the old chazanim recall the ta’ amé ha-kerià of the primeval Italian minhag and these are still recited during the reading of the “second Sefer” on the Holidays. Meanwhile the reading of the Parashá and the Haftará in the central synagogue is modeled after Sephardic te’amim which were partially adapted to the rules of the Italian rite. I will treat this more in detail in a few pages. Altogether Sephardic, with distinctions between the Catalan and the Spanish or Castilian are the nocturnal “Selichoth” that I was able to record in their entirety. Likewise the Sephardic influence is evident in the domestic songs of the “mishmarà” (wake).

I didn’t find anything of Sicilian origin in the Roman oral traditions. There are however various musical manuscripts that were performed in the “Scole”, dating from the late 1800s. Thus, I won’t exclude the possibility that upon closer examination, we might find some elements derived from the Sicilian tradition.

The rite practiced in the Synagogue of Rome, in terms of textual referents, is more or less that of the Italian Machazor, following the Bologna edition of 1501, with additions such as the “Lechà dodì” which could have not been included in the original version.

In my view, the songs that are the most uniquely Italian are also the most ancient. These are to be found in the recitation of the Psalms still practiced on Saturday mornings in responsorial and antiphonal forms, with traditional melodic formulas. They reflect the purest and most ancient Eastern-Semitic traditions and they also show a certain parallelism with biblical poetry. The Friday night formulas specific to the italkì ritual, are also very ancient and they seem not to have been contaminated by recent stylistic innovations in organ music.

An interesting variation of the Italian-Roman rite can be found in Pitigliano, once the “Little Jerusalem” of Tuscany. Unfortunately the community is today all but disbanded and its musical traditions are conserved only in a repository in Florence.

It is difficult to say – and only an in-depth investigation will be able to demonstrate it – whether the Sephardic influences in the Roman rite can be traced to the arrival of refugees from the Iberian peninsula and Naples in the 16th and 17th centuries or if they are rather the residual Palestinian influence of Rabbi Hazan. Hazan was a music lover who occupied the Roman rabbinical chair between between 1829 and 1836 – interrupting the long 19th vacancy of that post.

In Pitigliano, an isolated small town, the liturgical music of the Italian rite has been well preserved and remains uncontaminated by Sephardic influences. Nevertheless, not even Pitigliano was spared by the late 19th century modernist frenzy. A certain Pancani is said to have ‘modernized’ the most popular aspects of the musical ritual – for example, he altered the Lechà Dodi to reflect the lyrical-pathetic style of the late 1800s, thereby discarding the simpler and more ancient melodies which, in Hebrew, echoed popular Italian music of the 17th and 18th centuries.

2) In Northern Italy, from Florence to Turin and Padua, the Italian rite was practiced by communities established during the 1400s, when the first money-lending banks opened. Most likely the banks were the handy work of Jews who had migrated from the more ancient communities in the South. In Tuscany, Veneto, Emilia-Romagna and along the Adriatic coast, however, the Italian rite was variously influenced and gradually replaced by a mixture of the German and Spanish rites (brought to Italy by refugees from those countries after the 15th century). The refugees, just like those in our time, eventually adopted the language, pronunciation and the singing style of Italian Jews – but they also clung fiercely to their own ritual. Not satisfied with merely keeping their minhaghim and communal organization, they also fought to have these integrated into the ritual practice of the community. There is documentation of this interesting ‘struggle’ to preserve original liturgical music traditions in Italy and we might compare it to similar battles in Turkey, Persia, Greece, Yemen, Babylon and the Ukraine.

It is a well-known fact that, between the 16th and 18th centuries, the contemptuous imposition of the Sephardic Jews ultimately led to the replacement of the more ancient rites and traditions that had been practiced in Turkey and Greece. These included the Minhag Romania or the liturgical customs of the Byzantine Empire dating from the early centuries of the Common Era. The Minhag Romania, as ancient as the Italian rite, evolved based on the Palestinian traditions from the time of the Gheonim. Even in Persia the original minhag Paras was overtaken, in the last centuries, by the influence of rabbis of Sephardic origin. There was an analogous struggle between traditions in Yemen. And in our time, an analogous fight – but in the reverse sense – is happening in Erez Israel. This time the crisis has been resolved against the Sephardic and Oriental Jews who, although they represent the majority, have been unable to shake the impact of Ashkenazi customs. Ashkenazi Jews have assimilated the language and pronunciation of their Sephardic counterparts but, in exchange, they have imposed their own liturgical traditions and European musical sensibility. Today the official ‘Israeli rite’ – on the radio, in state ceremonies and in the elementary schools -, is the Ashkenazi rite, even though they are the more recent immigrants.

In the last decade, the italkì rite has re-gained some ground in Italy. This is partly due to the influence of the 19th century Piedmontese rabbis; partly to a patriotic spirit and anti-German zeal that followed the wars for independence and finally, to the formation of new Kehilloth in large urban centers where there weren’t any traditional precedents. For example, the Italian Synagogue of Jerusalem adopted the ritual text of the machazor of Bologna.

Today we find the Italian rite in the new kehilloth in Milan and Bologna. The Italian rite is now practiced even in Padua which, although already an Ashkenazi hub in the 15th Century, remained hostage to the Sephardic Venetian influence for many centuries. In Ancona, the Levantine rite has prevailed after a long struggle. In Ferrara the Italian rite vies for control over various German and Sephardic influences. Meanwhile Florence was strongly Italian for four centuries. The cantorial pomposity of the Livornese Jews conquered the central synagogue and banished the Italian to the tiny “Oratory of Via dell’Oche”. Finally, after the war, Fernando Belgrado, whose splendid voice was considered to epitomize Sephardic warmth, eliminated the monotonous Italian cantillation altogether.

I discovered residual traces of the Italian rite in Padua, Ancona, Ferrara and Florence, through a series of interviews with elderly members of these communities. In Reggio Emilia I was not able to record the last cantor of the Ottolenghi ‘dynasty’. But I had the benefit of previous recordings thanks to the help of Dr. Marzi, a professor of Byzantine music in Cremona.

The Piedmontese – conservative by their very nature – have maintained the Italian rite entirely intact. Both Turin and Alessandria, since the formation of their kehilloth around 1400-1500, have remained faithful to the Italian rite. The liturgy is most purely “Italian” in Alessandria whereas Turin has suffered some modernist stylistic contaminations (especially with regard to choral singing and organ music). Fortunately the organ hasn’t altered the biblical reading and the cantillation of Tish’à Beav and Kippur remains uncontaminated. The solid liturgical traditions of the Torinese rabbis combined with the uninterrupted chain of Italian Rabbanim (so unlike their Roman counterparts in the 19th century!) provide us with a precious testimony of very ancient “neumatic” readings of the Torà, the Prophets and even the Psalms. That these biblical readings can be identified with the Italian rites of Florence, Rome and Ancona, leads us to believe that they have a common origin in the medieval communities of Southern Italy – and thus in a period of time when the ancient minhag of Erez Israel gave birth to the minhag italkì.

Thanks to its conservatism, Piedmont provides us with important documentation in two other areas as well: popular songs in dialect and the pronunciation of Hebrew. Passover songs, typically the “Crava ca la pastürava” – taken from “Chad Ghadià” but not literally translated – demonstrate ancient influences and an interesting relationship between Jewish song and local folkloristic traditions. The pronunciation of Piemontese Jews, as captured in these phono-magnetic documents, (“ü” for the kibbuz, “u” for the Kamez hatuf, “s” (silent) for both the shin – and with slight emphasis – for the zadi, etc.) constitutes an important tool for studying the phonetics and dialectology of Diaspora Hebrew.

3) More recent than the Italian, but undoubtedly of medieval origin, is the minhag called “APAM” an acronym from the three Piedmontese kehilloth – Asti, Fossano and Moncalvo. Outside of these cites the minhag Lombardia, an important example of a trait-d’union between the Franco-Germanic rites and the Italian-Byzantine, has disappeared altogether. They are the only remaining testimony of French liturgical customs – often more authentic and pure than the Italian (which were perpetually changing due to a constant influx of new influences). The Jews of French origin, who settled in the smaller cities of the Piedmont between the 13th and 14th centuries, conserved their liturgical and musical traditions. The Piedmontese stubbornness and the liturgical continuity in peasant towns, makes this phenomenon comparable to the Waldensian experience.

Of the three Communities, Fossano has ceased to exist for several decades now and its practices and traditions can be found only in traces in Cuneo. The Temple of Moncalvo was dismantled during the war and re-erected in Casale. Only in Asti do these rare ‘French’ traditions continue to thrive and only in the feast day liturgies of Rosh-Ha-Shanà and Kippur. It is really only on those days that the Machazor departs from the Ashkenazi rite and only during the Yamin Noraim that the prayers contained in the “kuntress” or “quinternett” are recited. The quinternett has never been edited or printed. The many hand-written copies that once circulated around Asti are now collected in various libraries in the United States, England and Erez Israel.

As noted, the cantillation of the minhag APAM contains archaisms. On the one hand, they are very closely related to Ashkenazi music (from the Alsace and Southern Germany) and on the other, to the gradual and antiphonal sequences of the ancient Gregorian ritual – dating from the 11th to the 14th centuries. We should recall that the late Middle Ages gave rise to the literatures and new poetic forms of the romance languages and that this period also saw an evolution in musical sensibility and preferences from the “tonal” variety of the ancient world to the “modal” and modern. Moreover, these developments took place first and foremost in Provence and Northern Italy – precisely where the Minhag AMAP and its communities originated. Thus,identifying and recording these documents is especially important as it is useful to compare them with the minhag “Carpentras” of the Communities of Avignon and the Comtat Venaissin in Provence. Much of the music of the French Communities is today extinct but a great deal of it was prudently transcribed and thus still available for study.

The two principle “informants” in my recording campaign have been a man from Asti and a man from Moncalvo, both professors of literature and principles at the Jewish Schools in Turin. Their advanced age has taken nothing away from the vitality of their voices. Moreover their characteristic Jewish warmth brought me back to the old world and the Piedmontese ‘Ghettos’ of the 19th Century.

4) The Sephardic minhag conquered Italy by sea and it attacked the peninsula on two fronts, infiltrating both the Adriatic and Tyrrhenian coastlines. As noted, the Italians Jews gave up territory only after a long and difficult struggle – beginning with the first disembarkations at Naples and Genoa in 1492 and at Livorno a century later and culminating in the decisive conquest of Florence by David Prato and Fernando Belgrado in the last few decades.

With the exception of Rome, there weren’t any substantial contaminationes in the music of the Italian minhag. The Italian minhag was forced to make way for the disruptive arrival of refugees from Sicily, the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa.

Once Livorno was conquered, it in turn conquered Pisa, Viareggio and Naples. However, Florence, which had long cultivated its own musical traditions, was able to extend its influence to Genoa and then all the way to Ramat Gan in Israel and Alexandria in Egypt.

The differences between the Spanish and Italian musical-liturgical traditions were due, in large part, to the way in which each pronounced Hebrew (and this made a fusion of the two traditions nearly impossible). The Sephardic pronunciation was neo-Latin, oxytone, iambic and truncated, as it was linked, especially in ancient biblical neumes, to the Latin rhythm or even to older Palestinian traditions. The Italian pronunciation instead, was paroxytone, and trochaic.

In Livorno to this day, “beth” and “taw” without dagesh are pronounced as “b” and “t”: Bagitto, the Livornese Jewish dialect, is rife with Spanish elements and it even contains evidence of a North African influence. This is most apparent in the dialectal music – primarily in the songs for Purim, Passover and other familial occasions.

In the Purim songs – which I had the pleasure of recording in the rare, warm voice of a Rav of Labronic origin (now Chief Rabbi) – we find the Sephardic-Oriental tradition of the ‘travestimento’. In this device, an aria typical of vernacular folk music is adapted as sacred music or vice versa. This was the system that gave rise to the headlining of Psalms “‘al ayeleth ha-shachar” or “‘al ha-sheminith” or rather, the arrangement of a psalm to the tune of a popular folk aria that begins with those words. The res-Kolo of the Syrian-Christian liturgy, Western-christian antiphony, the Byzantine “heirmos” and finally, the work of the Sephardic composers Israel Nagiara and Menahem de Lonzano, the last Jewish paitanim – living in Turkey in the 16th and 17th centuries-, all demonstrate a similar use of popular folk music. Nagiara and Menahem integrated the first words adapted from Turkish, Arab, Greek and Spanish folk songs into their sacred hymnals. The goal of this exercise was wholly didactic – to substitute religious hymns for popular tunes – all the while appropriating the easy and familiar melodies of the latter. However, as in the example of the Livornese Purim songs, this practice easily arose from the simple and innate musicality of Mediterranean folk culture.

5) The cantillation of the Sephardic-Levantine minhag, practiced today in Venice, Ancona and part of Ferrara differs, characteristically, from that of the Tyrrhenian kehilloth – with which it shares only a few patterns of biblical reading. It dates from a later period and its formation was due to the arrival of Levantine merchants from Turkey who absorbed the Western (Ponentino) minhag of the marranos from Ferrara and Venice. Tied to the Venetian Republic, its fate varied over time. Until a century ago, Spanish Venetian [Jewish] communities existed in Padua, Gorizia, Trieste, Spalato and Ragusa – today they are all extinct. A few movements and recitativi bear traces of a Balkan and Romaniot, therefore of Byzantine influences. It is not surprising that among the many Jews who flocked to Venice, there were Eastern Jews, Sephardic Jews and ‘Romaniot’. Eastern Jews came to Italy for many reasons ranging from commerce to hardship and persecution. Some also found in Italy a tolerant refuge from the long disputes and religious tyranny of the 17th century Sephardic rabbis of Valona, Janina, Arta and Corfù. Extremely interesting is a few examples of biblical ta’am – as demonstrated in the atnach which was recited in iambic verse and not sung as in the Sephardic Tyrrhenian practice. This cantillation is very similar, in fact, to versified readings of the New Testament in the Greek Orthodox liturgy.

The ending of each verse is truncated as in Sephardic-Tyrrhenian music and not paroxytone as in Italian custom, but the internal rhyme is mostly three-syllable – almost barcarolle, dactylic rather than iambic or trochaic. This predilection for the tercet, in the internal rhyme as well in the verse endings, is of course a defining characteristic Adriatic folk music – found in Venice, Puglia, Albania and Dalmatia. The songs of the San Nicandro or Sannicandro converts – that I recorded in Israel – have the same characteristics.

The proselytes of San Nicandro Garganico created an impressive collection of hymns for their Jewish-leaning religious functions – inspired by the Bible and perhaps also by protestant Pentecostal communities. Their language is that of Southern Italian vernacular folk music (assonance prevails over rhyme). The rhythms and melodies are taken from, or liberally inspired by, Apulian folk music. They capture “live” the passage from popular to sacred music: what happened in San Nicandro between 1932 and 1948 is exactly what happened in Venice three centuries ago.

6) Between 1500 and 1700, the Italian Ashkenazi communities flourished around three epicenters: Casale Monferrato in the Piedmont, Verona and Padua in the Veneto and finally Casalmaggiore, Firenzuola and lower Lombardy. The few traces and records available in Lombardy today show that the community was already in decline by 1710. In that year the Italian Ashkenazi kehilloth had their Machazor re-printed by Bragadina in a special “in folio” edition. Firenzuola d’Arda does not figure in the list of those communities who ordered the reprint. In the temple of Firenzuola, which is today abandoned to rodents, I found a large number of copies of the previous edition, the Machazor “Hadrat Kodesh,” printed in Venice in 1585. One hypothesis for their dissipation is that they had been chased out by the Spaniards and had take refuge in Mantua and Monferrato. In Piedmont, at one time, the German minhag extended its influence as far as Cuorgnè and Acqui and in the Veneto as far as Gorizia, San Daniele del Friuli and even all the way to Ferrara.

Reconstructing the musical liturgical practices of the German-Italian musical rite is today a difficult undertaking. Traces can be found in Verona; the Triestine liturgy has suffered influences of every kind and my investigation there yielded little or nothing. Further, the songs and music I collected came from somewhat dubious sources – Paduans living in Milan or Venetians who had relocated to Rome. Moreover, my research shows only how certain melodies of German origin were Italianized and softened. Some demonstrate evidence of 17th century-style embellishments while others, such as in the case of the Ma’os Zur, end high in the scale at “mi” rather than “do”. This latter stylistic practice is typical of Northern Italian folk music which draws on Gregorian or “Phrygian” modes rather than the major key.

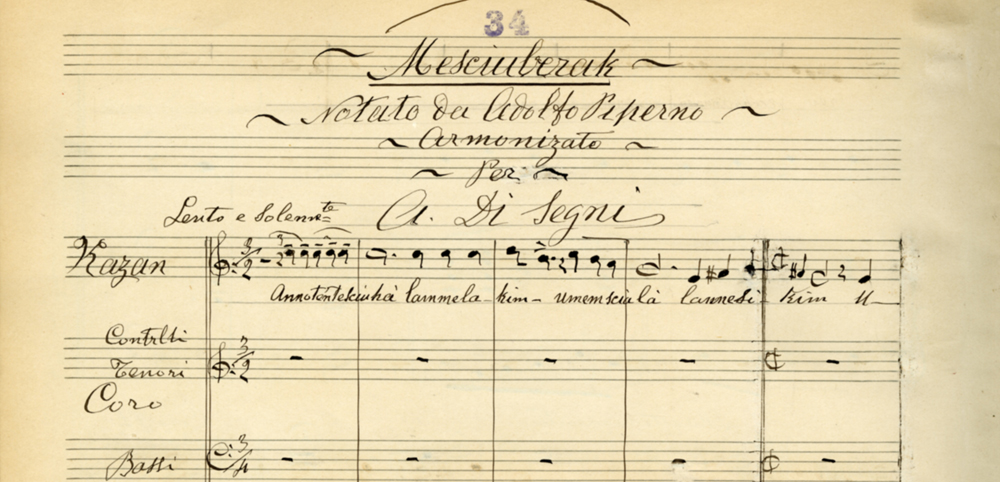

As noted, various transcriptions of songs and music associated with the German-Italian rite have survived: those by Benedetto Marcello (1724) and those of the Psalms by cantor Abraham Segre of Casale (1600). According to Idelson, Segre also prepared another transcription (treating diverse aspects of the ritual) which is now unfortunately lost.

The Polish-Ukrainian Jewish traditions reflect a variety of influences from Tzigane (Hungarian gypsy) to Mongolian, and Tartar music. Full of augmented seconds and nostalgic embellishments, these had a profound effect on the Ashkenazi rituals of Southwestern Germany – which had been stable between the 9th and 15th centuries. (The Yiddish language itself is a testament to Mittelhochdeutsch!). Thus, it is interesting to note that the Italian variety of that minhag – however altered to reflect local preferences and practices, nonetheless bears witness to the original German rite. As in the cases of the French minhag conserved in Asti, and the Byzantine traces preserved today in Venice, this example shows how the Italian Jewish communities provide important testimony – both in the form of archaic documents and in ritual practice – to traditions now extinct in their countries of origin. The incredible variety of songs (or verses), including special music for every holiday and occasion, enriches a musical-liturgical patrimony already full of noteworthy “inventions” – which are in turn, largely reflective of a folkloric style typical of 17th century Venice.