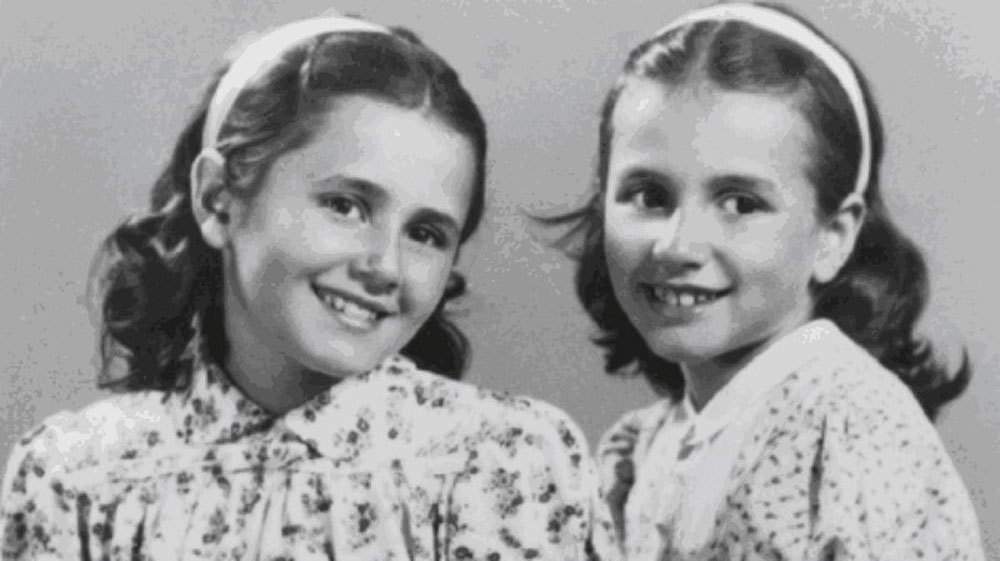

A memoir by Andra and Tatiana Bucci. Forward by Ruth Franklin

Andra and Tatiana Bucci, Always Remember Your Name, translated by Ann Goldstein. Astra House

By all rights, this book should not exist. The survival of anyone imprisoned in the vast death factory of Auschwitz is unusual enough. But the survival of a child is another matter entirely. Those tall or strong enough to pass—“eighteen,” prisoners whisper to new arrivals in Imre Kertész’s autobiographical novel Fate lessness, “tell them you’re eighteen”—were treated as adults, laboring and suffering alongside the general population of prisoners. But almost all young children, as Tatiana and Andra Bucci acknowledge in their astonishing memoir, were murdered by the Nazis immediately upon arrival.

Yet the Bucci sisters made it through not only the initial selection but three seasons at Auschwitz, surviving until the camp was liberated by the Soviet Army on January 27, 1945. The question of how they were able to live is ultimately unanswerable, a reminder that despite all the research conducted over the past seven decades into the inner workings of the Final Solution, much of what took place in the camps will always remain mysterious. There is a common perception that the Nazis ran their extermination camps like a well-oiled machine, with every cog lined up to generate murder with maximum efficiency, but in fact much was up to chance. The mood of a guard could spell the difference between life and death.

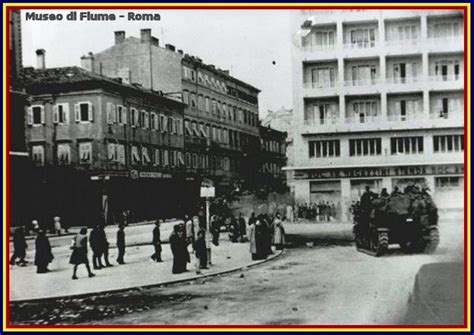

According to the official record, on April 4, 1944, 29 male prisoners and 53 female prisoners were selected from the Bucci sisters’ transport from Trieste and Istria; the remaining 103 deportees, including Tatiana and Andra’s grandmother, Nonna Rosa, and their aunt Sonia, were gassed. Perhaps, the sisters speculate, they were spared because of their mixed parentage: their father, an Italian sailor captured off South Africa when Italy entered the war in 1940 and imprisoned near Johannesburg until 1945, was Catholic. Their mother had been baptized together with the children several years earlier as a precaution; after their initial arrest, she tried to insist on the family’s Catholic bona fides. Surely it was her “quick-wittedness,” they argue, that bought them life in Auschwitz. But the likelier theory, which the sisters also entertain, is that, at ages six and four, they looked like twins—the special obsession of the infamous Nazi doctor Josef Mengele. Disinfected and tattooed, they were separated from their mother and taken to the Kinder block, the barracks for children, most of whom were the subjects of Mengele’s notorious experiments.

The sisters write their memoir as adults; their book benefits from the maturity of their perspective. But it is always apparent that their memories of the camp are the memories of children. (A note on terminology: the sisters were held in the division of the camp known as Auschwitz II/Birkenau, the extermination site and concentration camp for Jewish prisoners, and usually refer to it as Birkenau.) So young were they that Andra started wetting the bed again—a problem for her sister, sleeping beneath her. During the day they were allowed to play outside the barrack, though of course there were no toys: “We play with nothing, only our imaginations.” In the summer, they used pebbles, “because there’s no grass around, just a lot of heavy gray mud.” In winter, they tried to make snow- balls, but, without gloves, their fingers were quickly frozen. No matter the season, their games were conducted amid “pyramids of corpses.”

Most children at Auschwitz died within a year. The sisters survived, in part, owing to the attention of their mother, who managed to visit them occasionally, each time insisting that they repeat their names and their identity as Italians: perhaps because she wanted them to remember that they had a home beyond the camp, but also, more practically, so that she would be able to find them when they were inevitably separated. They also benefited from the goodwill of a blockova, or block leader, who brought them extra food and clothing and warned them not to volunteer when the guards offered a group of children a chance to “go see their mammas”—a cruel deception that brought about the death of their cousin Sergio. Andra remembers another “kind German” who gave them chocolate and white bread. More than anything, they had each other. “We stuck to each other like a stamp to a postcard,” they write.

A pediatrician described the three hundred or so children discovered in Auschwitz at liberation as so starved that “the bones were the only part of their bodies that weighed anything.” Because of their emaciated state, most were assumed to be younger than their actual ages. They had eye infections (possibly the result of experimentation), skin infections, bruises, even tuberculosis. The psychological damage, harder to quantify, must have been no less severe. At an orphanage outside Prague to which the sisters were initially sent, Andra locked herself in the bathroom rather than admit that she was sick, terrified of being taken to an infirmary like the one in the camp. Another child was punished for stealing soap—a justifiable theft after being forced to live in filth.

The turning point is the sisters’ transfer to Lingfield House, a group home outside London run by Alice Goldberger, a German refugee who trained with Anna Freud. On a beautiful country estate, Goldberger—clearly a modern-day saint—managed to create a paradise of peace and security for survivor children. Surrounded by food, toys, and caring adults, the sisters were “reborn.” One day, Goldberger showed them their parents’ wedding photo and told them both of their parents were alive. Within months, the girls were repatriated to Italy. Reunited with their mother at the train station in Rome, they were thronged by people waving pictures at them, asking for information about their children’s fate. In a later interview, Andra would remember how overwhelmed she felt by her inability to tell the crowd of bereft parents what they wanted to hear. “When these people asked me, ‘Have you seen this person?’ I would say, ‘Perhaps I saw them.’ Because I thought it was cruel to say, ‘I didn’t see them.’”

The sisters’ mother “chose not to harass us with memories.” She got rid of all artifacts from that period of their lives and refused to speak about the camp experience with them. “Between us was an impenetrable, total silence,” they write. The contemporary reader might imagine such a silence as damaging. But the sisters prefer to see it as healing, “a way of protecting us.” Not only did their mother not want them to suffer from what they would learn about her own experience, she wanted them “to look forward and not back.” They returned to a life not unlike the one they had left behind, that of a “normal Italian family,” and went on to marry and have families of their own. There are reminders throughout of those who were not as lucky, namely the sisters’ aunt Gisella, Sergio’s mother, who was never able to accept the truth about her son’s fate, preferring to believe that he was still alive somewhere. “A child so lovely, she said to comfort herself, couldn’t help being welcomed and cared for by someone in some corner of the world.”

Over the course of this brief and spare book, I was surprised to find myself often moved to tears, particularly by the sisters’ account of a teacher at Lingfield House who took Andra home with her and cuddled with her in front of a fireplace to help her feel safe. The International Tracing Service of the Red Cross had a “children’s room” containing some three hundred thousand files: so many lost children, so many heartbroken parents. It is a consolation, however small, to know that a few of those children were, miracu- lously, welcomed and cared for by people whose kindness helped to make up for the brutality of others. The sisters reflect that it was not only the Germans who were respon- sible for the Holocaust but also the Italians and others who facilitated the Germans: “For this reason, too, we should all feel, in a small way, responsible for what happened.” Yet many, too, worked to rebuild what the Nazis destroyed; and for them we can all feel thankful.