Original title: Beliefs; Judaism’s beloved Haggadah, 550 years in print, offers consistent themes in abundant variation.

Gathered tonight and tomorrow around tables all over the world to celebrate Passover, Jews will pick up hundreds of versions of the Haggadah. Containing biblical texts, prayers, ritual directions, explanations and songs for the annual reimagining of the ancient Israelites’ liberation from slavery, the Haggadah is one book and many books.

Much has been made of the politically radical, feminist, vegetarian, even Disneyfied Haggadot (”The Prince of Egypt”) that have been published in recent years, along with ”family” versions oriented toward children, versions with illuminations from medieval Jewish manuscripts, versions accompanied by scholarly or literary commentary.

Since Johann Gutenberg perfected his printing press 550 years ago, at least 4,000 printed editions of the Passover Haggadah have appeared. Before that, there were centuries of hand-lettered and illuminated manuscripts.

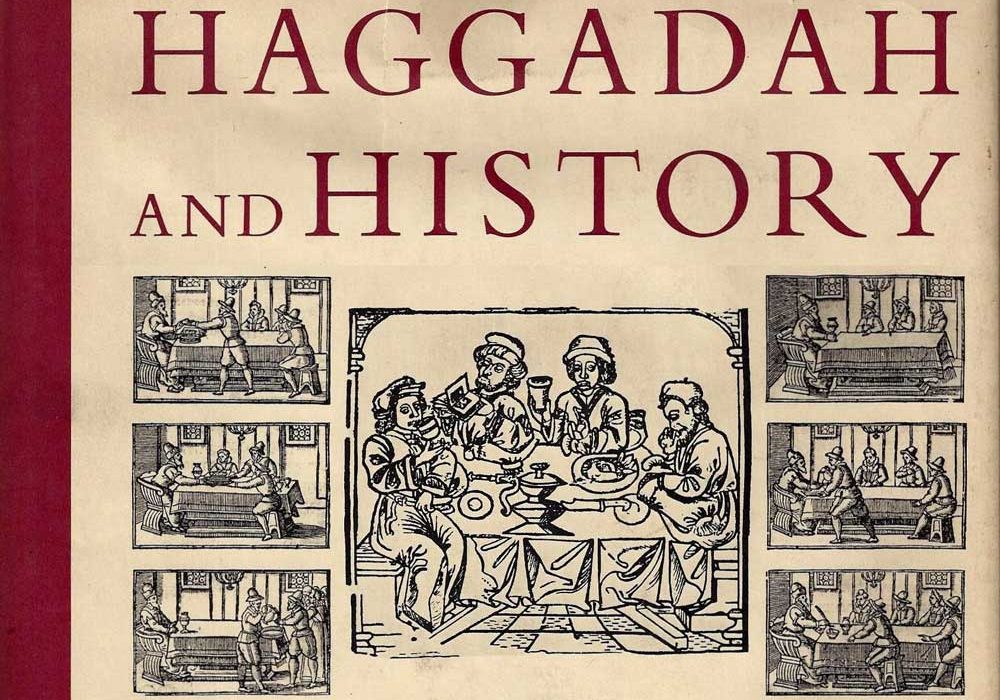

In ”Haggadah and History” (Jewish Publication Society, 1975), a survey of printed Haggadot from the collections of Harvard University and the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi shows that despite the relatively unchanging ritual of the Seder, Haggadot were always interacting with changing environments.

Reissued in 1997, Mr. Yerushalmi’s book, with 200 black-and-white plates from four centuries of Haggadot, shows the remarkable continuity in illustrated Passover themes: the pre-Passover search with candle and feather to remove all minute crumbs of anything leavened, people baking matzo, the 13 stages of the Seder celebration, the 10 plagues inflicted on Pharaoh’s Egypt, the 4 questioning sons (wise, wicked, simple and unable even to ask the question).

But in the early centuries of printing, within this continuity, were fascinating changes and borrowings. An illustration in the great Prague Haggadah of 1526 shows Abraham crossing the Euphrates River in a rowboat. In later editions from Venice and Mantua, Italy, the rowboat metamorphoses into a gondola.

Renderings of the Temple frequently take their shape from the Dome of the Rock mosque. Renaissance printings of the Haggadah feature borrowed border designs rife with squirming putti or portraying Mars, Minerva and other classical deities that Jews had once abhorred but now considered mere decoration.

In a 1560 Haggadah, a portrait of the wise son, traditionally represented by a mature figure with a beard, is an unabashed copy of Michelangelo’s portrayal of the prophet Jeremiah in the Sistine Chapel.

In another Haggadah, printed a few years later, the Jeremiah figure is labeled a wise elder replying to the wise son, and then, on another page, is presented as the Rabbi El’azar ben Azariah, a sage quoted in the Haggadah and known for his long white beard.

The copperplate engravings illustrating one of the most pictorially influential Haggadot, printed in Amsterdam in 1695, turn out to be reworkings by a convert to Judaism from Christianity of a Swiss Christian artist’s engravings of events from biblical and Roman history.

Jews and Jewish printers were constantly being hounded out of this or that part of Europe, but artistically they were anything but isolated from the contemporary culture.

The author traces Jewish history not only in the illustrations of the Haggadah but also in the added translations of the Hebrew text. Editions began appearing with translations in the various tongues, like Ladino and Yiddish, that were written in Hebrew but married the language to Italian, Spanish or German.

From North Africa to Central Asia, from Denmark to Iraq, Haggadot were tailored to the languages of Jewish communities. The Haskala, the militant Jewish Enlightenment movement that advocated entering the European cultural mainstream, campaigned for Haggadot with modern European languages.

An 1846 Haggadah for Jews in Bombay features illustrations derived from forerunners printed in Amsterdam and Venice centuries before, but the Hebrew is accompanied with explanations in Marathi characters. By 1874, a Haggadah from Poona, India, not only had Marathi translations but also distinctly Indian illustrations.

Adding translations and integrating commentaries into the Haggadah presented new challenges in typography and design. Even today, when color printing and the flexibility of computer graphics and composition make it much easier to separate the different elements, some Haggadot can be a chore to follow.

”Haggadah and History” does not hesitate to include a few parodies and worse. In 1885, underpaid Hebrew teachers in Odessa, Ukraine, produced a parody asking, ”How does teaching differ from all other professions in the world?” The answer involved hunger, student disruptions and abuse from the community.

A 1927 Soviet ”Haggadah for Believers and Atheists” is in a different category. In place of the traditional pronouncement over the burning of leaven, the Communist text urged that ”all the aristocrats, bourgeois and their helpers” — a long list of ”counterrevolutionaries” was inserted here, including Mensheviks, Jewish socialists and Zionists — ”be consumed in the fire of the revolution.” If any counterrevolutionaries remained, like the invisible specks of leaven, the Communist text consigned them to the secret police.

This Haggadah denounced Passover itself as a trick of rabbis rather than a festival of freedom.

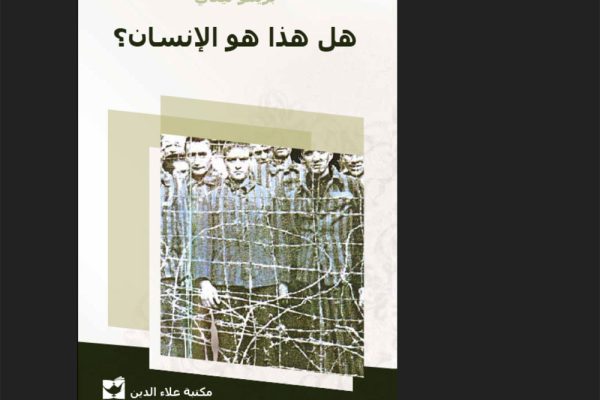

The Haggadot from the Holocaust years and from the years of postwar mourning in Europe and building in Israel are charged with history.

It was on the verge of that tragedy, however, that the most powerful images of the Passover struggle of good and evil, slavery, arrogance, bloodshed and retribution, seemed to fill the Haggadot. The peril had gripped talent without yet overwhelming it.

The reproductions in ”Haggadah and History” from efforts by the Polish artist Joseph Budko in 1921 and Jacob Steinhardt in Berlin in 1923, by Istvan Zador in Budapest in 1924 and Otto Geismar in Berlin in 1928 replace conventional treatments with the jarring resources of modernism and contrasting, ominous uses of black and white.

When Mr. Yerushalmi wrote ”Haggadah and History,” he said of his subject: ”Scholars have meditated upon it, children delight in it. A book for philosophers and for the folk, it has been reprinted more often and in more places than any other Jewish classic.”

”The Haggadah,” he wrote, ”is in many ways the most popular and beloved of Jewish books.”