Amelia Rosselli’s Serie ospedaliera among the poet’s most haunting, imaginatively intense and formally rigorous collections, has just been published by New Directions as Hospital Series, translated by Deborah Woodard, Roberta Antognini, and Giuseppe Leporace .

Originally published in Italian by Il Saggiatore, Milano, in 1969 Serie Ospedaliera also contained an earlier long poem, La Libellula, The Dragonfly, composed in 1958.

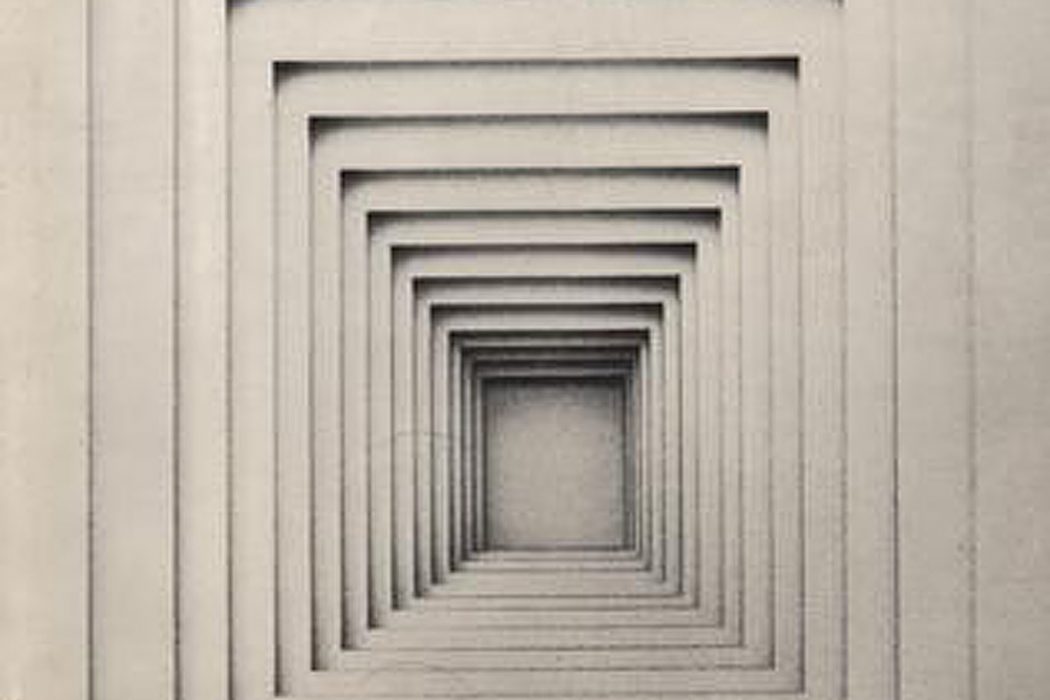

For the first edition, Rosselli insisted on an IBM monospaced font (one in which each letter occupied the same amount of space), and on a layout with each poem printed on its own recto, accentuating a geometric and formal rigor.

Each stanza can be read in equal amount of time, composing a square, echoing the arresting image chosen for the cover: a series of squares receding one inside the other.

Rosselli worked on the poems of Hospital Series from 1963 to 1965, yet in an interview with Renato Minore (in Il Messaggero, Feb 2, 1984) she stated they were written all at once during a fifteen day creative burst.

Following Amelia Rosselli’s first collection of poems Variazioni belliche (War Variations), the title Hospital Series again contains a musical term: series is a reference to serial music which Rosselli was studying.

Alessandro Cassin interviewed Deborah Woodard a poet and translator living in Seattle and Roberta Antognini, Associate Professor of Italian and Chair of Italian at Vassar College.

Rosselli’s oeuvre consists of the following collection s of poetry :

Variazioni belliche, Milano, Garzanti, 1964.

Serie ospedaliera, Milano, Il Saggiatore, 1969.

Documento (1966-1973), Milano, Garzanti, 1976.

Primi scritti 1952-1963, Milano, Guanda, 1980.

Impromptu, Genova, San Marco dei Giustiniani, 1981.

Appunti sparsi e persi, 1966-1977. Poesie, Reggio Emilia, Aelia Laelia, 1983. (2nd Edition by Edizioni Empiria, Rome, 1997.)

La libellula, Milano, SE, 1985.

Antologia poetica, Giacinto Spagnoletti, editor. Milano, Garzanti, 1987.

Impromptu, bilingual edition curated by A. Rosselli( French traanslation postface by J.-Ch. Vegliante), Paris, Tour de Babel, 1987.

Sonno-Sleep (1953-1966), Roma, Rossi & Spera, 1989.

Sleep. Poesie in inglese, Milano, Garzanti, 1992.

Variazioni belliche, Fondazione Marino Piazzolla, 1995, Plinio Perilli editor preface by Pier Paolo Pasolini.

Le poesie, Milano, Garzanti, 1997

L’opera poetica, a cura di S. Giovannuzzi, con la collaborazione per gli apparati critici di F. Carbognin, C. Carpita, S. De March, G. Palli Baroni, E. Tandello, introduzione di E. Tandello, Milano, Mondadori, 2012 (“I Meridiani”).

The prose volumes:

Prime prose italiane (1954)

Nota (1967-1968)

Diario ottuso. 1954-1968, Roma, IBN, 1990.

The essays:

Una scrittura plurale. Saggi e interventi critici, Novara, Interlinea, 2004.

Neoavanguardia e dintorni, with Edoardo Sanguineti and Elio Pagliarani, Palermo, Palumbo, 2004.

Lettere a Pasolini. 1962-1969, Genova, S. Marco dei Giustiniani, 2008.

È vostra la vita che ho perso. Conversazioni e interviste 1964-1995, Florence, Le Lettere, 2010.

Présentation d’A. Rosselli (La libellule), in Recours au Poème (Paris).

Published translations by Amelia Rosselli:

Emily Dickinson: Tutte le Poesie. Milan, Mondadori, 1997

Evans, Paul. Dialogo tra un poeta e una musa. Rome, Fondazione Piazzolla, 1991.

Plath, Sylvia. In Le muse inquietanti e altre poesie. Milan, Guanda, 1965. 2nd Edition, Milan, Garzanti 1985.

In English translation:

Hospital Series, translated by Roberta Antognini, Giuseppe Leporace and Deborah Woodard, New York, New Directions, 2015.

Impromptu: A Trilingual Edition, translated by Diana Thow, Montreal, Guernica Editions , 2014.

Locomotrix Selected Poetry and Prose of Amelia Rosselli, a Bilingual Edition, edited and translated by Jennifer Scappettone. Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 2012.

The Dragonfly: A Selection of Poems: 1953-1981. Translated by Deborah Woodard and Giuseppe Leporace. New York, Chelsea, Editions, 2009.

War Variations: A Bilingual Edition. Translated by Lucia Re and Paul Vangelisti. Los Angeles, Green Integer, 2005

In French translation:

Impromtu. Translated by Jean-Charles Vegliante. Paris, Tour de Babel, 1987

In Japanese translation:

Tatakai no vuarieshon. Translated by Tadahiko Wada. Tokio, Shoshi Yamada, 1993.

In Spanish Translation:

Poesìas. Translated By Alessandra Merlo in collaboration with Juan Pablo Roa and Roberta Raffetto. Montblanc, Tarragona, Igitur, 2004.

Books on Amelia Rosselli:

Baldacci, Alessandro. Amelia Rosselli. Laterza, Rome, 2007. 2nd Ed.2014.

Baldacci, Alessandro. Fra tragico e assurdo: Benn, Beckett e Celan nella poetica di Amelia Rosselli. Edizioni Università Di Cassino, Cassino, 2006.

Barile, Laura. Laura Barile legge Amelia Rosselli. Nottetempo, Rome, 2014.

Bisanti, Tatiana. L’opera plurilingue di Amelia Rosselli. Edizioni ETS, Pisa 2007.

Carbognin, Francesco. Le armoniose dissonanze. “Spazi metrici” e intertestualità nella poesia di Amelia Rosselli. Gedit Edizioni, Bologna, 2008.

De March, Silvia. Amelia Rosselli tra poesia e storia. L’Ancora del Mediterraneo, Naples, 2006.

Fusco, Florinda. Amelia Rosselli. La scrittura e l’interpretazione. Palumbo, Palermo, 2008.

Loreto, Antonio. I santi padri di Amelia Rosselli. “Variazioni belliche” e l’avanguardia. Arcipelago Edizioni, Novara, 2014

La Penna Daniela. La Promessa di un semplice linguaggio: la dinamica delle fonti nell’opera trilingue di Amelia Rosselli. Carocci, Rome, 2009

Limone, Giuseppe and Simone Visciola Eds. I Rosselli: eresia creativa, eredità originale. Guida, Naples, 2005.

Passannanti, Erminia. Sulla Poesia di Amelia Rosselli, Brindin Press, 2012.

Sanelli, Massimo. Il pragma: testi per Amelia Rosselli. Dedalus, Naples, 2000.

Savinio, Stella, and Rosaria Lo Russo. Amelia Rosselli… e l’assillo è rima. In La furia dei venti contrari, A documentary film. Le Lettere Florence, 2007.

Snodgrass, Ann. Knowing Noise: The English Poems of Amelia Rosselli. Studies in Italian Culture: Literature in History. New York, Peter Lang , 2001.

Tandello, Emmanuela. Amelia Rosselli: la fanciulla e l’infinito. Donzelli, Rome, 2007.

Amelia Rosselli was born in Paris in 1930, the daughter of Marion Cave, an English leftist political activist, and Carlo Rosselli, an Italian anti-Fascist leader, the founder, with his brother Nello, of Giustizia e Libertà, a liberal socialist movement. Giustizia e Libertà rapidly became the main non-marxist Italian resistance movement.

Before Carlo Rosselli and Marion Cave were reunited in Paris in 1929, Carlo had escaped from a Fascist penal colony on the island of Lipari, while Marion, pregnant with Amelia, had been arrested for complicity in Carlo’s escape. Carlo, Marion and their three children lived in France as political exiles. In 1937 Carlo and his brother Nello were assassinated at Bagnole de l’Orne by La Cagoule (a French Fascist militia group) acting on orders from Mussolini.

Soon after the funeral of Amelia’s father and uncle the Rosselli extended family (the grandmother —the playwrite— Amelia Pincherle Rosselli, Marion, Nello’s widow, Maria Tedesco Rosselli and all the children) moved to Switzerland, England and finally, in 1940, to the United States.

The family settled in Larchmont, New York. Amelia attended Mamaroneck’s Public School where she graduated in 1945.

The Rossellis returned to Italy in 1946, but soon after, Marion and the children went to London, where Amelia attended one more year of high school required to access to university in Europe. In England, she also studied piano, violin and composition. Contemporary music and ethnomusicology remained a strong interest throughout her life.

Her mother died in England in 1949, plunging Amelia, then 19, into a deep depression. Back in Rome, she worked on her poetry, and lived by translating from English and French. Her relationship with poet Rocco Scotellaro and his untimely death in 1953, cast a long shadow on the rest of her life.

Taking a distance from her fathers’ political legacy she joined the Communist Party in 1958.

Among her principal literary influences, Rosselli often mentioned Dante, Rimbaud, Campana, Joyce, Kafka, Scipione and Montale.

Elio Vittorini and Pier Paolo Pasolini were the first to recognized Rosselli’s unique poetic voice, before the publication in 1964 of her first book of poems, Variazioni belliche.

While her main focus was poetry, Rosselli had a keen interest in music theory, which brought her into contact with the composers Luigi Dallapiccola, John Cage, David Tudor, Luciano Berio and Karlheinz Stockhausen. In the 1960’s she also participated in theatrical performances by Aldo Braibanti and Carmelo Bene.

With each subsequent book, of poetry — Serie ospedaliera (1969) Documento (1976), Primi scritti (1980), Appunti sparsi e persi (1966-77), Impromptu (1981), Antologia poetica (1987), Sleep (1992) — she refined a bold approach to language transcending conventional syntax and grammar with her incandescent verse.

Between writer’s blocks and bouts with depressions her last years were occasionally brightened by public readings and closeness to a new generation of young poets. Her life ended in suicide on February 11, 1996.

Alessandro Cassin. When did you encounter the work of Amelia Rosselli, and what was your initial response to it? Given for formidable challenges of Rosselli’s language, what drew you to undertake this translation?

Deborah Woodard. I think it helped that, when I started, I had no idea what I was getting into. An old friend of mine, Linda Lappin, who is herself a translator, sent me a bundle of books she was discarding from her library, and Variazioni belliche was among them. I stowed the books in the lower compartment of a sideboard in the dining room and, eventually, drew out the Rosselli. I opened it up and put it back. It was too difficult to parse. But then having lost interest in another translation project, which seemed too thin, I went back into the sideboard stash, and picked up the Rosselli once again. Fascination trumped doubt. I translated a sample poem, brought it to Giuseppe Leporace, whose classes I was auditing at the University of Washington, and we began translating. When we learned that Lucia Re and Paul Vangelisti’s translation of Variazioni belliche was forthcoming from Green Integer, we made the decision to switch to Hospital Series.

Roberta Antognini. I truly encountered Amelia Rosselli and her poetry through Deborah. I teach Italian language and Literature at Vassar. A few years ago, realizing that in the foreign literature classroom, translation is inseparable from writing and reading, teaching and learning, I decided to build on my lifelong passion for translation by developing a seminar on literary translation from Italian to English, for fourth year students of Italian. As a consequence of this course, I found myself increasingly immersed in translation studies, fascinated by a field that defines me as an individual and, in this country, as a professional. Although I had some previous experience as a translator—I translated Shirley Jackson’s short story “The Lottery” and Teodolinda Barolini’s book, The Undivine Comedy, into Italian—it was this course that whetted my appetite for translation. The first time that I offered it, I invited Deborah Woodard for a class presentation on her work on Amelia Rosselli. And I soon discovered that Rosselli is one of the most interesting and innovative Italian poets of the past half-century. As she was both a poet who wrote in three languages—Italian, English and French—and a translator, questions of translation are central to her work. Deborah asked me to collaborate with her in preparing Hospital Series for publication and I enthusiastically accepted.

AC Amelia Rosselli’s first collection of poems, Variazioni belliche, was published in Italy in 1964, and her last, Sleep, in 1992. How do you explain the long delay in translations and critical attention in America?

DW Translation doesn’t fare all that well in the United States in general. And poetry itself is a hard sell. Each translation that comes out adds to the momentum and reaches out to new readers. Having translated Rosselli for twenty years, I know that she only gets better. This process of bestowing upon her the attention she deserves, though still achingly slow, is irreversible.

RA One can even say that Amelia Rosselli is more appreciated in the United States than in Italy. Although quite known in Italy, she has not yet received the critical attention she deserves. Partly because her poetry requires such a strenuous, almost physical, mental effort, and partly because Rosselli was a particularly difficult individual, an outsider somewhat isolated from the contemporary literary scene.

AC Now at last, thanks to your work, that of Lucia Re and Paul Vangelisti, and of Jennifer Scappettone, there are a variety of different translations available. Many scholars are beginning to study her work. Do you have any hypotheses for why her moment has finally arrived?

DW As I said above, it is a slow build. But we are getting there.

RA There is a tendency among American scholars in Italian studies to translate, especially women. To the point that, for instance, we have the paradox of Italian original texts by sixteenth, seventeenth hundred women writers available in Italian in a modern edition only because of the English translation. I believe Amelia is part of this trend.

AC Translations are often done in teams: could you describe the specific nature of the collaboration between you, Giuseppe Leporace and Roberta Antognini on Hospital Series?

DW Giuseppe and I worked on Hospital Series for several years. We put the translation on the back burner when Alfredo de Palchi of Chelsea Editions invited us to compile The Dragonfly: A selection of Poems 1953-1981. By the time I returned to Hospital Series, several new books on Rosselli had been published, and the Mondadori definitive edition of her work was in the offing. It was time to take a fresh look at Hospital Series. When Roberta and I met at Vassar, and subsequently attended the Barnard symposium in 2011 on Rosselli, we agreed to work together to review Hospital Series and prepare it for publication. We came to terms over a couple glasses of red wine. Thanks to Roberta, the translation is crisper and more accurate, and there is more of Amelia’s music in it and a pinch more of her word play, all of which makes me very happy.

RA Even though I was revising more than translating, the experience of co-translating Serie ospedaliera with Deborah has been exhilarating. In Amelia, tradition and innovation are so deeply intertwined that almost every word is a challenge. When Deborah was looking into the depth of the target language, I was digging into the source language as profoundly as I could, trying to find out as much as I could in order to convey to her the movement of Amelia’s poetic voice.

AC In 2009 you translated with Giuseppe Leporace a selection of Amelia Rosselli’s poems (The Dragonfly. A selection of Poems 1953-1981, Chelsea Editions). That earlier collection included 17 poems from Hospital Series. In your new book you have reworked those same poems, at time making different choices of words, word order and entire verses. Can you contrast the experience of working on the two translations and describe how your understanding of this material has changed?

For example, in your first translation of Sex violent as an object (whitened quarry of marble)

You first translated: “Non gaudente, non sapiente serpentinamente influenzato da esempi illustri o illustrazioni di candore, per la pace e per l’anima purulava” as: “Not pleasure-seeking, not learned serpentinely influenced by illustrious examples or illustrations of candor, it festered for peace and for the soul.

In your new translation it becomes:

Not sybaritic nor sage

serpentinely influenced by illustrious examples or illustrations

of candor, it festered for peace and for the soul.

DW I wanted to speed the lines up a bit, too, as this poem moves so beautifully. In general, few translations are written in stone. With a poet such as Rosselli, one can always have a new idea because she presents us with concentric circles of sound and meaning. I consulted the thesaurus, came up with “sybarite” and “sage,” and loved the sure-footedness of these new choices. In fact, as Roberta pointed out to me, “gaudente” and “sapiente” are hapax words, occurring only once in the text. We needed something a little out of the ordinary, for a poet who is always out of the ordinary.

AC Now that several translators have worked on Amelia Rosselli’s poetry, the English language reader has choices. One measure of the difficulty of translating Rosselli is highlighted by the fact that even the title of her first collection, Variazioni belliche, has been translated alternatively as War Variations, Martial Variations and Bellicose Variations… Would you care to elaborate?

DW I’m not completely convinced by any of these translations of Rosselli’s title. At the time, I felt that Martial Variations flowed well, but, rethinking that choice, I fear that it suggests a regimented display that is the complete antithesis of what the text is about. War Variations is accurate but sacrifices the Latinate mellifluousness of the original. At the moment, I think that I prefer Bellicose Variations (Scappettone) because the attitude, the bellicosity of the narrator’s voice, is so prominent in these poems. It is more of a mouthful in English than in Italian, but, for whatever reason, this title is tricky. Fortunately, Hospital Series is always going to be translated as just that (I think!).

RA The discussion of this title provides a great example of the way Deborah and I worked on the final draft of Hospital Series: literally dissecting words and debating solutions. In this case, the great fascination of the vaguely oxymoronic title Variazioni belliche comes from the combination of the (also but not only) musical term variazioni with the adjective bellico that retains the Latin etymology (the noun would be “guerra” which has the same German origin of the English “war”). However, bellico means “pertaining to war”, rather than “bellicose”, eager to fight, for which there is the adjective bellicoso. Hence, the variations are not bellicose, they just belong to war. Personally I like best the more literal translation of War Variations, which in English has a nice alliteration to it.

AC Rosselli’s experimentation with language takes radical new turns from book to book. Having translated both earlier and later work, how would you characterize the specific language of Hospital Series?

DW With the exception of the heightened lyricism of the Campana-influenced “La Libellula: panegirico alla libertà” (“The Dragonfly: panegyric to liberty”), I didn’t find the language between her first two books to be markedly dissimilar. Hospital Series is a bit more meditative than Variazioni belliche at times, perhaps. The issues are the same, but the theater is smaller and more intimate—again, with the notable exception of “The Dragonfly”, which was written earlier. Documento strikes a very different note, but I can’t adequately characterize the ways in which its language differs as of yet. I might provisionally term it more austere.

AC Do you plan to translate more of her work in the future?

DW Yes, once our schedules synch up, Roberta and I will be reviewing Rosselli’s poetic prose / veiled autobiography Diario Ottuso (Obtuse Diary), which I initially translated with Giuseppe Leporace for The Dragonfly, and which I worked on with another translator, Dario de Pasquale, as well. I love this little book of “prosa d’arte.” Then, finally, Roberta and I will turn our attention to Documento (Document). Documento is a challenge, to say the least, but we are drawn to the magnitude of this text. It is an entire landscape, and a very social and political one, it would appear.

RA All of Amelia’s poetry is characterized by an inner tension between the geometry of the prosody and the freedom of the language. Amelia considered Documento her most mature work, and, if we intend for maturity a sort of crystallization of this tension, it probably is.

AC How, if at all, do you feel that your work on Rosselli has impacted your own poetic practice?

DW I was very influenced by “The Dragonfly,” specifically by the way Rosselli interrogates lyrical imagery at the same time as she rejuvenates it. In my view, she renovates the lyrical line by finding ways to distort it, if that makes any sense, and by stopping it in its tracks and then picking it up again. I learned a lot from Amelia about timing. Her ear is impeccable. The extended riffs of “The Dragonfly” gave me a sense of freedom—the poem is, after all, a panegyric to liberty. I hope that Documento will give me another key, somehow.