Alessandro Cassin is the director of Centro Primo Levi’s online magazine Printed Matter and CPL Editions which published over 15 books since its debut in 2014. Coming from a tradition of publishing —his father published the first edition of If This Is A Man in English—Cassin began working in experimental theater and was awarded the Premio Ruggero Rimini 1989 for Il Presidente Schreber. He has been a cultural reporter for publications including L’Espresso and Diario. He is a contributor of The Brooklyn Rail. His book Whispers: Ulay on Ulay co-authored with Maria Rus Bojan received the 2015 AICA Netherlands Award. He coordinated the publication of Laurence Butch Morris’ The Art of Conduction edited by Daniela Veronesi (Karma, 2017). He is the author of The Scandal of the Imagination a film about the life and work of Aldo Braibanti ( 2021.) During the pandemic he wrote A Fiesole, bambino.

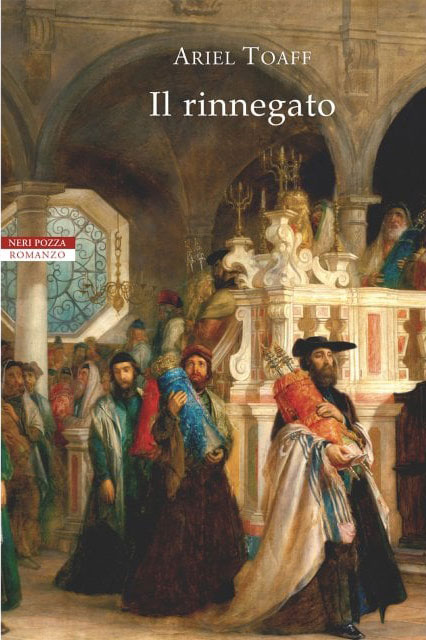

On a November morning in 1840, a young boy discovers the body of David Ajash, an Italian kabbalist rabbi of Algerian origin, under an olive tree, in the outskirts of Nablus. Homicide or suicide? The doubt remains, past the end of Il Rinnegato (Neri Pozza, Milano, 2021) (The renegade), the captivating literary debut in the form of a meticulously documented historical-mystery novel by Ariel Toaff.

The literary device is the son of the Rabbi immersing himself in his estranged father’s diary-testament, retracing adventures, and misfortunes consumed amidst religious intrigues, powerful amulets, Freemasonry, conversions, and murder attempts. From Ottoman Palestine, Ajash’s story transports the reader to early 19th Century Livorno, a vital Jewish center connecting North Africa, Western Europe, and Palestine through publishing and intellectual debate.

More than a fictionalized biography, Il Rinnegato seamlessly merges a wealth of historical questions and hypotheses into the fabric of a work of literary fiction. All of this while portraying in vivid brushstrokes The Jewish Nation of Livorno in the staggering vitality of its hay day.

As the dissolute life of the libertine rabbi unfolds against a background of a rapidly changing world. We are propelled into the small Sephardic Community Livorno, navigating complex cabalistic debates, religious orthodoxy, Hebrew printing, as well as foods, smells, brothels, and shifting alliances.

Rabbi Ajash neither believes in Judaism or Christianity, only in Kabbalah: his compass for understanding a bewildering inner and outer reality.

Ajash behaves as if he were convinced that one must plunge to the bottom of perdition only then to access the highest spheres of knowledge. While reading like a page-turner, Il Rinnegato drives the reader beyond the plot to discover — on multiple levels— the fascinating complexities of 19th Century Jewish life on the different shores of the Mediterranean.

The novel depicts human existence as nonlinear but built upon unexpected twists, dead ends, new beginnings, and re-invention. When all else fails, giving up one’s name and assuming a new one can be a way to divert avert destiny. The kabbalists around David Ajash’s dying father bestow him a new name to give him more life; David himself assumes new identities first when he converts to Christianity and later when he returns to Judaism. Ultimately, this highly engaging narrative poses many important and timely questions without attempting definitive answers, leading us to the open ending.

Alessandro Cassin: Writing your first novel in your late seventies seems to me a sign of great vitality and aplomb. What prompted a scholar and historian like yourself to evoke the world around a controversial nineteenth-century cabalist rabbi through a novel rather than an essay?

Ariel Toaff: I think that when writing an essay we are limited by written documentation. Historical research can provide background on Jewish life in a multi-ethnic city with a singular history like Livorno but not much on this specific cabalist rabbi. The novel goes beyond these limits and tries to fill the gaps in the documentation, addressing in the realm of the imagination the contradictions, perplexities, doubts, and the inner world of this Rabbi. In this sense, we can perhaps approach an understanding of this individual’s probable, or at least possible, reality.

A.C. Like you, your protagonist, Rabbi David Ajash, spent his life between Italy and the Middle East. Although born in the late 1700s, Rabbi Ajash is a contemporary: a restless, contradictory, nonconformist man who continually reinvents himself. How much do we know about David Ajash, and how much does your novel take poetic liberties with his story?

A.T. In a report by the massari (the governance) of the Jewish Community of Livorno on May 17, 1833, we read that “David Ajash has condemnable conduct for the non-observance of religious precepts and the scandalous obscenity of his customs: he is devoted to women and to the filthiest of vices. He is accused of the embezzlement of money destined to religious institutions and communities of the Holy Land. He is unworthy to be a father as he has abandoned, for many years, his wife and children. In short, he has abandoned his native religion to avoid family care and more easily satisfy his lustful desires.” A week later, David Ajash asked to be baptized, and his request was accepted with the recommendation that his catechumenate be held in Pisa. This is what one finds in the written records, but we do not know to what extent this is colored by tendentious and hostile judgment on the man. In the Archive of the Jewish Community of Livorno, there is a substantial file concerning David Ajash (Serie Minute 1833-34, folder. 18). For many years, it should be noted that his relationship with the Jewish Nation (Community) of Livorno turned out not to be problematic or controversial but friendly and cordial. Proof of this is a copy of his kabbalistic commentary on the Haggadah of Pesach, entitled Kol David, “The voice of David” (Livorno, Molco and Sadun, 1825) in my possession with a dedication in golden Hebrew characters on the cover of green Moroccan leather. The recipient is one of the Jewish Nation of Livorno elders, Moise di Salomone Coen Bacri.

A.C. A rabbi, son of a rabbi and, later, father of a rabbi –his instinct, the contingencies of life, a desire for adventure Ajash does the unimaginable for a man of his tradition: he converts to Catholicism, after clashing with the Jewish leadership. Later he retraces his steps and re-embraces Judaism. This to and fro between religions occurs against the backdrop of a rapidly changing Jewish world that feared, after emancipation, the treacherous dangers of assimilation into Christianity. What drew you to this controversial figure who ended up being considered “a renegade” by both Jews and Catholics?

A.T. David Ajash expresses his intention to become a Christian and, in fact, converts in Pisa. But he does not take this serious step with conviction and a light heart. He clearly wants to take revenge on the Jewish Community that banned him, marginalized him, and considered him a heretic. At heart, David is a man who lacks faith in God and in the men who claim to represent Him. He has no faith in religion, in any religion as such. Therefore, he has no problem alternating between Judaism and Christianity, returning, disenchanted, to Judaism at the end of his days. The fact that he is considered a traitor and a renegade both by Jews and Christians does not induce him to adapt and adhere to the law of the strongest but rather strengthens his skepticism and contempt for Jewish and Christian leaders. His freedom of thought and choice is absolute and not subject to calculations. It is the path he has chosen, and, despite contradictions and missteps, he never abandons, whatever the cost. And it will cost him his life.

A.C. The novel follows the protagonist’s adventurous and sometimes picaresque events, as he recklessly leads a dissolute existence of unbound freedoms, libertine demeanor, and few moral qualms. Yet, among constant dangers, pitfalls, violent opposition, and unpredictable outcomes, his chosen path fails to deliver the fulfillment he was seeking. So why, despite all his daring, is he denied the fullness of happiness?

A.T. David is never fulfilled nor satisfied with himself. He is constantly searching for new emotions, unexpected events, and adventures, which are often dangerous and with little prospect. He clings to the talismans and amulets of the Kabbalah as the only lifeline in a storm of events that he cannot control, dodging obstacles that threaten him, often set in motion by himself. Sudden perils await him around the corner. In the best cases, his choices lead to a momentary joy; he is fully aware of this. Yet, he continues to search for answers, knowing he won’t be able to find them. He knows that a sudden and violent death awaits him at the end of his bumpy journey, but he does nothing to avoid or delay it. It is the fate of a man without peace, which he admits to being.

A.C. Il Rinnegato is perhaps the first historical thriller set in the Italian Jewish world. It operates on many different levels: it can be read as a compelling thriller, a window into the fragmented world of nineteenth-century Sephardic Judaism, and to some extent as an autobiographical reflection. I will not dwell on the intricacies of the plot so as not to reveal too much to future readers. I suggest, instead, that we focus on some of the many underlying themes: the geographical mobility within that world— Algeria, Livorno, Ferrara, Thessaloniki, Jerusalem, Nablus—; the religious upheaval and the impact of messianic movements from Sabbatai Zevi to Jacob Frank; the history of the Italian Jewish book and the centrality of Livorno; the relationship between Freemasonry and Judaism, to name but a few.

Perhaps we can begin from the movements between different worlds, not only geographic but also ideological, political, and religious, which seems to me a through-line of the novel. The father of the protagonist, a kabbalist of Algerian origin, had clashed with the pro-Jacobin Jews of Ferrara, become a rabbi in Siena, and later dissented with the rigid orthodoxy of the Jewish Nation of Livorno. Following his father, David Ajash learns to navigate different worlds with disenchantment and irony…

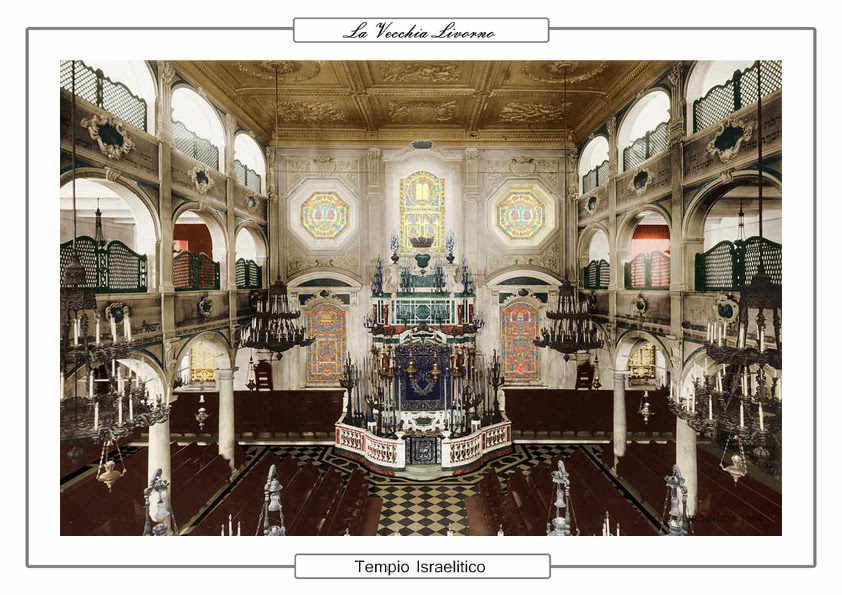

A.T. David Ajash lives in a rapidly changing world. He opens a window for us onto Italian Jewish life and, in the first place, on that of Livorno, a city that has always represented an exception. Unlike other Jewish centers in Italy, Livorno never had a ghetto. It was founded in the Renaissance, thus later than many other cities, and has its own and original physiognomy. Livorno constitutes a bridge between the Holy Land and the East, between the Maghreb and the Iberian Peninsula, between the German and French Jewish communities and the Jews who had settled in Italy centuries earlier and had different histories and particular identities. In Livorno, Jewish studies are steeped in the traditions of the Kabbalah. The Zohar is considered to be the most accredited interpretation of the Torah and the Bible in general. The teachings and beliefs of Livorno’s rabbis and sages are a far stretch from a rationalist vision of Jewish precepts and rituals. The “dialect” of the Jews of Livorno, neither Hebrew nor Italian, is a Judeo-Hispanic vernacular, full of Italianisms, called bagito or bagitto. The Community was formed by ethnic waves of different origins, Jews from other parts of Italy, Rome in particular, the Maghreb, the Balkans, Spain and Portugal, and the Middle East. Livorno was also an important Hebrew publishing center (with printing presses managed jointly by Jews and Christians) that served the communities of the Mediterranean basin from the seventeenth century to the mid-twentieth century, providing liturgical and ritualistic texts.

In Livorno, there were fierce clashes and debates within the rabbinic orthodoxy, entrenched in its institutions, religious courts, and censorship commissions. The local rabbis were strenuous defenders of the religious tradition and local customs and their exclusive right to elect the massari (governors) entrusted with leading the Jewish Nation. The rabbis themselves did not hesitate to adhere to Freemasonry. Some of the main lodges had among their members numerous Jews, including rabbis, mainly of North African origin, such as David Ajash, and the famous kabbalists Chaim Yosef David Azulay, known as the Chidah, the enigma, from the initials of his name, and the philosopher Elia Benamozegh. Incidentally, my grandfather Alfredo Sabato Toaff, Rabbi of Livorno in the first half of the twentieth century, was a disciple of Benamozegh.

A.C. In the age of the internet, it is not easy to imagine the relationships, the modes for the circulation of ideas, the exchanges between North African Jews, the Italian Jewish Communities, the yeshivot in Palestine, and on the horizon, the more open French Jewish world, or the preaching of an Ottoman Jew like Sabbatai Zevi. Beyond the events of the book, can you describe the nature and modalities of those exchanges?

A.T. The shadarim, as the envoys of the yeshivot of the Holy Land (Jerusalem, Hebron, and Safed) were called, came to Italy to raise funds, favoring the wealthiest and most consistent Sephardi communities, such as Livorno, Ferrara, and Venice. French culture, its language, and literature attracted and influenced the intellectual Jews of Livorno, many of whom were of Moroccan, Tunisian or Algerian origin and who sometimes wrote their works in French. Elia Benamozegh was not an isolated case, as we know.

A.C. Then as of now, one of the most formidable tools for the circulation of ideas is the book. David Ajash returns to Italy to publish a book. It was not a commercial enterprise but a way to express his specific relationship with Judaism. Printing a Hebrew book meant receiving the imprimatur, if not precisely the permission, from the rabbinate as well as finding a significant sum for the printing expenses. In those years, the publishers/printers in Livorno were a vital link between the various worlds you are talking about …

A.T. David Ajash’s grandfather, Jehudah, had himself moved from Algiers to Livorno, remaining in the city for a couple of years, from the beginning of 1756 to the end of 1757, and publishing seven works on Kabbalah and ritual. David’s father, Moise Giacobbe, had also edited a liturgical text printed in Livorno in 1790 and re-issued a few years later by the printer Lazzaro Sadun. At that time, there were five Hebrew printing presses in Livorno, managed jointly by Jews and Christians. One of them, “Tipografia Sadun e Molco” printed David Ajash’s Kol David, “the voice of David,” the cabalistic commentary on the Pesach Haggadah, which bears an acknowledgment to generous backers of the book, the Trieste entrepreneurs Vita Sabato Vivanti and Clemente Minerbi.

A.C. In order to publish his book, Ajash must accept to make significant changes imposed by the rabbinate. The pretext is that his description/interpretation of the Pesach ritual emphasizes aspects that the Catholic world may construe as foretelling or confirming the trinity dogma. Ajash agrees to edit the text but falls into a trap. The curses and prejudices against him (together with the insufficient scholarship of the censors) prevent a serene reading of his book, and therefore of its circulation. In this, there are obvious parallels with the events that accompanied the publication of your Pasque di Sangue (Passovers of Blood). Should a Jewish author (a rabbi, son of a rabbi) be bound by considerations on whether a book is “good for the Jews” before publishing it? What do you think the controversy around Pasque di Sangue has taught you? What else does Il Rinnegato suggest to us in this regard?

A.T. This is an insidious question, not easy to answer. David Ajash was forced to modify his text, bending to the pressures or rather to the impositions of the three rabbis, members of the commission of permits and prohibitions, issur ve’hetter, which functioned as a real censorship body. They decided which books were fit for publication, which ones were prohibited, and which needed to be partially or radically modified to be printed.

I want to refer to a personal story in which I was the protagonist despite myself and of which I still bear the scars. The media lynching to which I was subjected following the publication of Passovers of Blood in February 2007 is well known; therefore, I do not need to summarize. The censors were generally the self-appointed “righteous people” who, in rare cases, had read the book and judged it by hearsay. Nevertheless, the sad story has reinforced in my mind what I believe is the duty of a serious and independent intellectual: consistency and faithfulness to the principles in which he believes, without bending to the pressures, expediencies, or easy ways out of the bind.

A.C. You have written a story of a cultured, cosmopolitan man, full of initiative and inner resources, yet extremely vulnerable and perhaps psychologically frail. He does not seem to believe in Judaism when he is a Jew, nor in Christianity when he gets baptized; is his frailty caused by his lack of faith?

A.T. As Don Abbondio says in Alessandro Manzoni’s The Bethrothed, one cannot give oneself courage. So even those who are convinced atheists, like Ajash, cannot provide themself with faith if not by applying it as an ornamental plaster when it seems to them that it may be helpful.

A.C. For a long time in Italy, as in many other countries, Jews have embraced Freemasonry. The lodge you describe in the novel includes (like many in reality) not only Jews and atheists but also practicing Catholics and even clergy members. One of the arguments for the appeal of Freemasonry to Jews was its anticlerical component. Further, its system of mutual support, perceived as precious by Jews whose status within Christian society was often precarious. Do you have other explanations for the large Jewish adherence to Freemasonry of the 19th century, and do you think that today to some extent, this appeal persists still today?

A.T. In my youth in Livorno, I remember many Masons, even among the rabbis and those who regularly attended services in Via Micali. Reading the epitaphs on tombstones at cimitero dei Lupi, the Jewish Cemetery in Livorno, in some cases, we find explicit references to the deceased’s belonging to Freemasonry. The Jewish adhesion to the Masonic lodges had its roots, aside from anticlerical motivations, in the widely shared belief that Judaism, in its kabbalistic interpretation, spoke the same language of Freemasonry. It shared with Freemasonry its values and ideals of humanity and mutual support, and a similar organizational system. Being a Mason was not in contrast with the Jewish faith but confirmed it by updating it and making it more relevant. Today I have the clear impression that Freemasonry belongs to the past, for Jews in particular.

A.C. There is a lot about the father/son relationship in the novel and the strength and difficulties of communication between generations. As a boy, in a protective gesture for his father Moisè, David causes the violent death of a Freemason priest who had threatened his father. David’s eldest son, also called Moise, will accept the task of returning his baptized father to Judaism but will never be able to understand or forgive him. Could you elaborate on the novel’s take on the complexities of the father and son relationship?

A.T. In addition to illuminating the relationship between father and son, I would say the novel intends to underline the bonds, both manifest and subterranean, within the family.

Beyond its tensions and inevitable contrasts, the family is viewed as a single entity, including the past generations, which have influenced the present and help understand it in its various aspects. As a result, there is a mutual responsibility within the family and a sense of belonging that characterize its countenance, even in the most challenging and problematic moments. Thus, the Ajashs are always aware of the indestructible bonds that unite them, all of them: Moise, his father David, and their ancestors who arrived in Livorno from Algeria.

A.C. At sea, between Thessaloniki and Palestine, amid a storm, when shipwreck seemed inevitable, the reprobate David Ajash extracts a powerful Masonic amulet and calms the winds and high waves. The episode echo’s the story of Jonah, perhaps the most unconventional prophet of the Torah and the Koran. Talismans, amulets, Masonic symbols, magical thinking. With the advent of science and the Enlightenment, all this was put aside by both Jews and Western society. And yet, some of this has left a void that we can hardly fill. Would you like to comment?

A.T. The use of magical thinking, talismans, and good luck charms seem to have been shelved by Jews in the Western world. But it is not as simple as that, or at least it is not always like that. At my home in Tel Aviv, as before in Rome, there are three kabbalistic amulets in Hebrew hanging on the wall, which belonged to my father and formerly my grandfather. One, in particular, I always carry with me on all my trips. I don’t know if it protects me, but I love to believe that it does.