Moravia’s Bildungs-novella Gets New Life

Sometimes a new translation can unlock the hidden beauty of a work that had previously not gained its deserved attention.

This is what happened with Alberto Moravia’s short novel Agostino, republished by NYRB Classics in Michael’s F. Moore’s richly textured new translation.

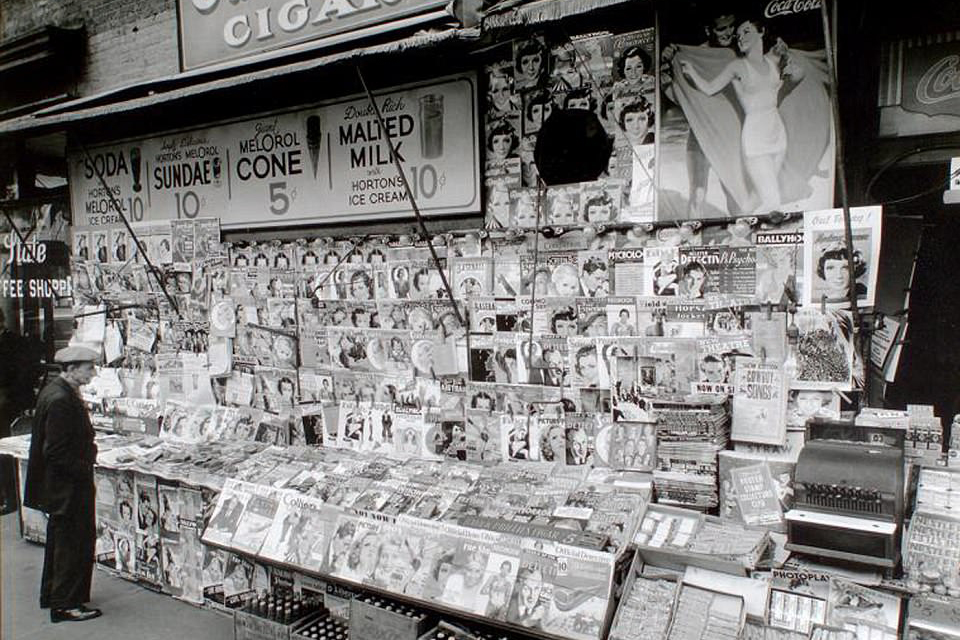

In its new English version, Publisher’s Weekly selected it among its “Best Summer Books 2014” defining it “a story told in only 100 perfect pages”.

Written in 1941, but not published because of the fascist censorship until 1944, Agostino is among the Italian writer’s very best works.

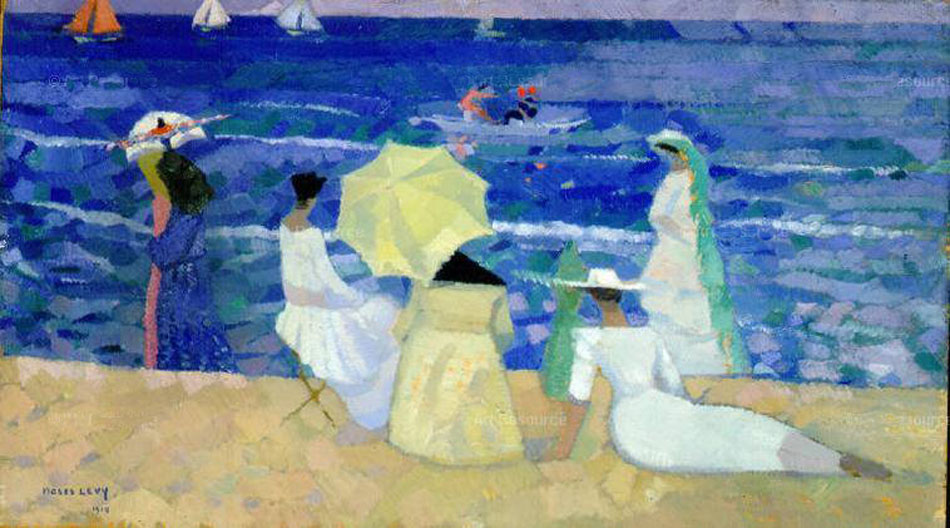

During a summer on a Mediterranean beach, Agostino —age thirteen— is vacationing with his recently widowed mother. The intimate, repetitive mother-son routine is suddenly interrupted by a young stranger’s courtship of the mother. Agostino, deeply hurt, falls in with a gang of local boys, opening his eyes to the brutality of life and suddenly aware of his privileged condition.

The raw experiences of that summer painfully reveal to him that “ he had bartered away his former innocence, not for the virile, serene condition he had aspired to, but rather for a confused hybrid state in which, without any form of recompense, the old repulsions were compounded by the new”.

Among the most appreciated Italian writers of the twentieth century in English translation, Moravia was born Alberto Pincherle into a bourgeois Venetian-Roman Jewish family. His paternal aunt, Amelia Pincherle Rosselli, was the mother of the antifascist hero brothers Carlo and Nello Rosselli. His sister, Adriana Pincherle, was a painter who had studied with Matisse and gained the praise of the critic Roberto Longhi.

From a young age Alberto struggled with a rare form of bone tuberculosis, which kept him in bed for months at a time. This allowed him plenty of time to read, achieving a vast literary culture. His first novel, Gli Indifferenti, 1929, established him as a major new voice in Italian literature, with a style that distanced itself from the D’Annunzio inspired high prose of the time.

In his perceptive translator’s note, Michael F. Moore takes issue with the older perception that Moravia was “tearing down the edifice of classical Italian literature[…]” “I would say instead that he is turning the literary tradition on his head, adopting the convention of courtly love poetry, but for earthly ends”.

Agostino brought Moravia his first literary prize and ushered in the themes and style of his mature novels. Like many of his later works, Agostino, adapted for the screen by Mauro Bolognini, has an almost cinematic visual and psychological acuity that has inspired many film directors. Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist is based on Moravia’s novel by the same title; Jean-Luc Godard’s Le Mépris comes from Il Disprezzo; Vittorio De Sica’s Two Women is an adaptation of La Ciociara, Damiano Damiani The Empty Canvas is based on La noia, as is L’Ennui by Cedric Kahn.

The New York Review Books Classics’ effort to offer new translations of Moravia’s work it to be commended.

Following Boredom, translated by William Weaver, 2004, and Contempt, translated by Tim Parks, 2004, Michael F. Moore’s Agostino, is pitch perfect in capturing Moravia’s voice and linguistic maneuverings.