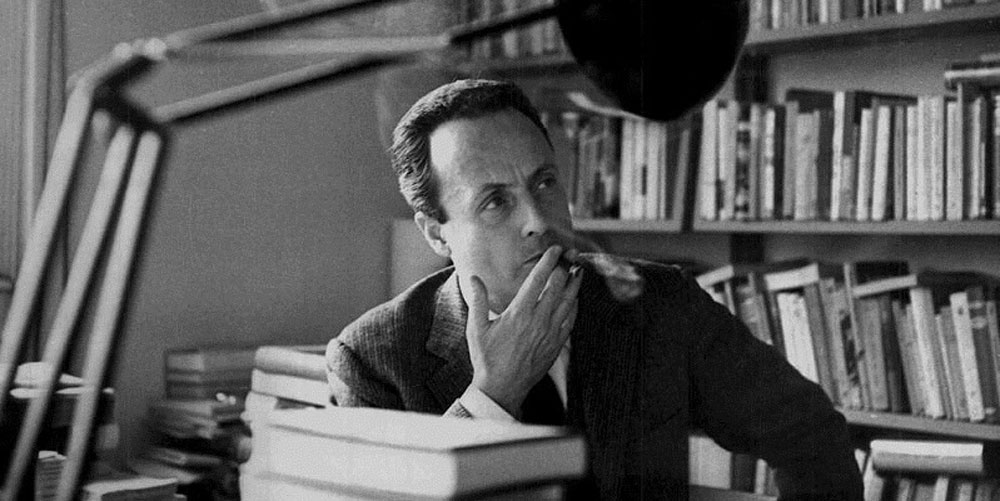

Bassani’s intervention in Vittorio De Sica’s Garden of the Finzi-Continis

The great writer asked for his name to be removed from the film in this article from l'Espresso in 1970, in the same week the film opened. Translated by Emily Gattuso (courtesy NYU Casa Italiana Zerilli Marimò) Giorgio Bassani I would like to go back to the very beginning of the strange story that I am going to tell: to the year 1963, so far away now, in which Documento Film secured the film rights to The Garden of the Finzi-Continis. Valerio Zurlini had urged them to obtain the rights. As soon as the purchase was completed, Documento Film did not hesitate to entrust Zurlini himself, already attached as director, with the task of preparing the script for the upcoming film. Zurlini immediately set to work. The screenwriter Salvatore Laurani was assigned to collaborate with him, and in a short time he put together a first draft. It was given to me to read. But what the hell could I say? Instead of drawing solely on The Garden of the Finzi-Continis, Zurlini and Laurani had taken cues from all my other books, from A Prospect of Ferrara to The Gold-Rimmed Glasses. In the Finzi-Continis’ garden, along with tennis, and alongside the novel’s original characters, one could encounter Elia Corcos, the doctor who is the protagonist of A Stroll Before Dinner; the aging socialist teacher of The Last Years of Clelia Trotti; Dr. Athos Fadigati, the distinguished gay physician at the center of The Gold-Rimmed Glasses; and so on; the combined effect was a bit humorous. Presented with such a work, for all the moral nobility and generosity of intentions that had inspired it (for what had Zurlini and Laurani meant to do, if not use my works as a palette with which to paint a kind of fresco of the Jewish tragedy in its entirety—Ferrarese, Italian, universal?), my reaction was one of sincere confusion. Fortunately, however, there was no need to waste too much time on that discussion; the film’s production did not seem to be a sure thing. And sure enough, the production was put on hold indefinitely. In the years that followed, Zurlini and Documento returned to the project more than once, never setting aside the first Zurlini-Laurani script, but little by little calling upon new screenwriters to modify it. I don't know all the names of those who treated the script. At a certain point, I know Tullio Pinelli worked on it, because he had the courtesy to consult me. Later Franco Brusati worked on it, giving up without adding much to what the screenwriters who had come before him had written. Then, around 1966, Zurlini definitively ceased his involvement with the production to focus on other projects and interests. But even without Zurlini’s participation, Documento did not give up the idea of making a film out of my novel. At the beginning of 1970 the producers turned to Vittorio De Sica, who gladly accepted the assignment. They also called upon me again, asking me if I would agree to collaborate on the project: but not truly to write the script, which they said they would do “on their own”—that is, assign it to a screenwriter they trusted—but rather to assist in revising the dialog. Invested, as I was, in the making of the film, I did not hesitate to accept. And, with renewed hope, I readied myself to read the new script. As soon as, after a bit of time had passed, I had the script in hand (the fourth so far), I was greatly disappointed. Vittorio Bonicelli, the writer chosen by Documento--I do not know whether if on the advice of Documento, or on his own--had refrained from trying anything new. Instead of starting from scratch, he too had relied on previous scripts, to get something that would preserve the best and discard the worst of the previous efforts. I could not but disapprove of this piecemeal work: and I expressed my disappointment immediately both to Documento and Bonicelli himself, who for his part, humble and intelligent man that he is, immediately recognized that the script had to be redone from scratch. And so it was that Documento, with approval from Vittorio De Sica, assigned Bonicelli and myself, working together and separately, to go back down that road that had led to such disappointment for Zurlini, Laurani, Pinelli, and Brusati. When, after a few weeks, Bonicelli and I delivered our script to Documento, we came to an agreement with the production company on the following points: 1. That our script, after a "technical" revision another screenwriter would carry out, would be returned to us "in a few days" so that we could make the final pass and complete a few parts that remained unfinished and pending. 2. That, in any case, the cinematic story would be interspersed, at intervals of various durations, with the recurring, realistic representation of the roundup of the Jews of Ferrara that took place after September 8, 1943, to be shot in black and white (the color of the documentaries produced by telejournalists, of stark and naked truth, without shame): that roundup which Giorgio, the protagonist of the film, the future author of the novel as a young man, would have witnessed, hidden and unseen. The narrative device of the black and white recurring sequences had been recognized as necessary for various reasons. Firstly, because it would have, in a way, represented the structure of the novel, which, as we know, is structured upon two distinct temporal planes, that of the present (the initial trip to Cerveteri, which falls on a Sunday in April 1957), and that of the past (the years 1938-1939); but, above all, because it would have saved the film from the inevitable dangers of flat, boring, comic book-style voiceovers. Contrary to the agreed-upon conditions, the script was returned to us almost two months later (I received it, to be precise, on July 8) nearly complete; so that any objections we might have had were immaterial. The supposedly "technical" revision carried out by the mysterious screenwriter so dear to Documento (the screenwriter Ugo Pirro, as I learned only then) had radically changed the Bassani-Bonicelli script. Our intention to respect the novel’s dual time structure was not respected whatsoever. And the new screenplay, full of voiceover very foreign to the spirit of the book, was now running decidedly on a single temporal plane, that of the past: with the effect, moreover, of reducing the figure of Giorgio to a role of little or no meaning. As it stood, his story was boring, sentimental, inconsequential, so that it was difficult to understand why a film had been dedicated to him. Many scenes were omitted: the flashes of Giorgio's dream; Giorgio and Malnate's dual visit to the brothels of Via delle Volte; Giorgio and Malnate's walks along the medieval streets of the city, at night; Micól's visit to the Jewish cemetery of the Lido in Venice reduced to a meaningless interlude; and many additions (that of the Grenoble pension, just to give the first example that comes to mind); and I am not, for now, even listing all the changes. But most importantly, the sequence of events was altered. Giorgio's trip to Grenoble happened at a different point compared to the original story, clearly giving the scene a completely different weight and meaning, not to mention rendering it didactic and arbitrary. The dialog was heavily altered: with speech that was either sentimental or melodramatic, or on the other hand, expositionary. One need only to look at p. 68 of the Pirro revision. In the Bassani-Bonicelli script on p. 51, the scene ended with Alberto's joke: "No, I don’t go out." In the Pirro revision, the dialogue continued. Alberto: No, I don’t go out... Anyway, where would I go? If it were possible to pick the faces one met on the street...I would go out. But whenever I did go out... I always felt I was being spied on... envied. Malnate: Whereas here, you get to pick the faces ... is this what you mean? Alberto: Not exactly. There are never many of us here. I never feel attacked. I know what you think: that I have no zest for life. But who can give me that? This addition, apart from any other consideration, profoundly modifies Alberto as a character, as he appeared in the novel and in the Bassani-Bonicelli script, transforming him into a verbose illustrator of his own neurosis. The historical-documentary additions, which the Pirro revision was full of, were all boring and misleading. The gag of the avant-garde artist run over by Giorgio's bicycle, on p. 143; another of a boy passing by on a bicycle with a swastika flag on its back fender (which was not original, but rather taken from a more recent story of mine, A Race to Opatija, well known to De Sica); or the other of the air siren that sounded mournfully during Alberto's funeral, on p. 309: all these little details had a clear didactic function. They were equivalent to knowing winks at the viewer, winks put there to educate a child, that is, the public. It must also be said that these supporting details were sometimes deprived of any basis of objective truth. In Italy, before 1943, September 8, 1943, Jews were not hunted down. The capture of Bruno Lattes, in a cinema no less(!), immediately after the battle of Tunisia, on p. 315 of the Pirro revision, therefore lacked all credibility. It was a true falsehood, to be rejected under any pretense. But what most displeased me, personally, was that my characters were used so freely, with so little reference to my work, in a way that would have been inappropriate even if they were marionettes. Although fine folk, the Finzi-Continis were not Rothschilds, carrying out correspondence with wealthy international relatives by mail! “Isac” and “Rachel,” mentioned on p. 278 onwards of the Pirro revision, distorted the Finzi-Continis, rendering a false and unflattering image of the family. Bruno Lattes, a character in The Giardino dei Finzi-Contini who also returns in my other works (The Last Years of Clelia Trotti, A Race to Opatija, The Rifle Girl), did not end up in Germany, in the gas chambers, as one would deduce from the Pirro revision, but was able to flee to America, returning in 1945 to revisit Ferrara, his native city. But the very worst of the revisions was the one that sent Giorgio's father to the Nazi concentration camps. I understand that it was convenient to arrange it like this, so that he could say, in the end, to Micól (and to the public), that Giorgio, the future author of The Garden of the Finzi-Continis, had been saved. But Giorgio, meanwhile, the future successful novelist, the future pathetic narrator of his teenage romance with the blonde Micól Finzi-Contini, how did that make him appear? By thus gettin away, and already resigning himself to mixing his writer's ink with his father's ashes, did he not make himself look like a monster? I did not answer Documento’s letter directly, in which I was asked to express my opinion about the Pirro revision and to bring forward any reservations that I deemed useful (the film, I repeat, was already almost completely finished: any useful intervention was impossible). I simply asked that Documento, through my lawyer, Franco Reggiani, exclude my name from the list of screenwriters. The Pirro revision had greatly altered the Bassani-Bonicelli script. Moreover, the idea of filling the film’s story with recurring flashes of the roundup of the Jews of Ferrara, which happened after September 8, 1943, had been definitively rejected. So it was not appropriate for my name to be on something that did not belong to me. Documento turned a deaf ear to my lawyer’s letter. While, over the next few months, the film was being completed, complete with editing, dubbing, mixing, etc., no one responded to my request not to be credited among the writers, or at least to discuss my request. Verbally, through intermediaries, and once also in writing, I was advised to wait. First I was to see the movie. This worked out well for them. I would have been very happy ... I only saw the film at the end of last month, in the presence of the magistrate. And since then, look here, the magistrate has found me in the right, and Documento and Vittorio De Sica in the wrong.