Whose (Who’s) Shakespeare? On Amelia Rosselli’s “Sleep”

“You are a stranger here,” declares the opening poem of Amelia Rosselli’s slim volume Sleep (2023), “and have no place among us.” This address comes between invocations of the “cool sweet fragrance” of “burnt” incense, of the work of “fat” and “tender” hands letting a hatchet cut “slittingly” into flesh-like dirt, of souls absconding to meet their “Maker” as fuel burns without end on earth—all antinomies that call to mind the Petrarchan tropes of waking and dozing, freezing and burning, falling and flight. Petrarch, like the author of these lines, was an exile, but these poems soon unravel into pseudo-archaic verses that evoke the brightest stars of the English Renaissance and their own riffs on the Petrarchan sonnet, from John Donne to Shakespeare. “The moment has come for a public of Anglo-American readers to grapple with these texts,” opined the critic-translator Jennifer Scappettone more than a decade ago.

Perhaps that moment is, at last, now. In November, NYRB Poets reissued Amelia Rosselli’s Sleep, the arcane, sole English-language collection of one of the most important Italophone postwar poets. Though little known among Anglophone readers, Rosselli is part of the Italian canon. Here, the bibliographic is instructive: she was canonized as one of “the greats” in Pier Vincenzo Mengaldo’s important 1977 Poeti italiani del Novecento (“Italian Poets of the Twentieth Century”); in 2012, a Meridiano—one of the most prestigious Italian editorial collections—was dedicated to her work; and now, her poems populate literature textbooks used throughout Italian high schools.

But Rosselli’s poetic idiom pushes against established, ethno-nationalist conventions of what we often understand to be “Italian,” or, for that matter, “English.” Reared in a storm of American and British English, Italian, and French—and versed in German, Arabic, Hebrew, Ancient Greek, and Latin—Rosselli bristled throughout her life at Italians noting her “off” pronunciation, or critics remarking upon her distorted, jumbled English: nouns used as verbs, verbs without subjects.

For her critics who interpreted these grammatical slippages as unintentional, the republication of Sleep through a prestigious American imprint declares otherwise. Penned in spurts between 1953 and 1966, the untitled poems that comprise Sleep were never published together until the 2012 Meridiano: in 1966, several poems appeared in John Ashbery’s Art and Literature and The Times Literary Supplement; in 1989, 20 poems were published as Sonno-Sleep (1953–1966) with Antonio Porta’s Italian translations; and in 1992, the scholar Emanuela Tandello translated a bilingual edition of 88 of the poems as Sleep: Poesie in inglese. Up until now, Sleep as a whole has been unavailable outside of Italy. This long overdue publication, along with Barry Schwabsky’s elegant introduction, then, calls for a revisit to Rosselli’s poetic project. What might we have to learn from this singular poet’s experiment in English-ing?

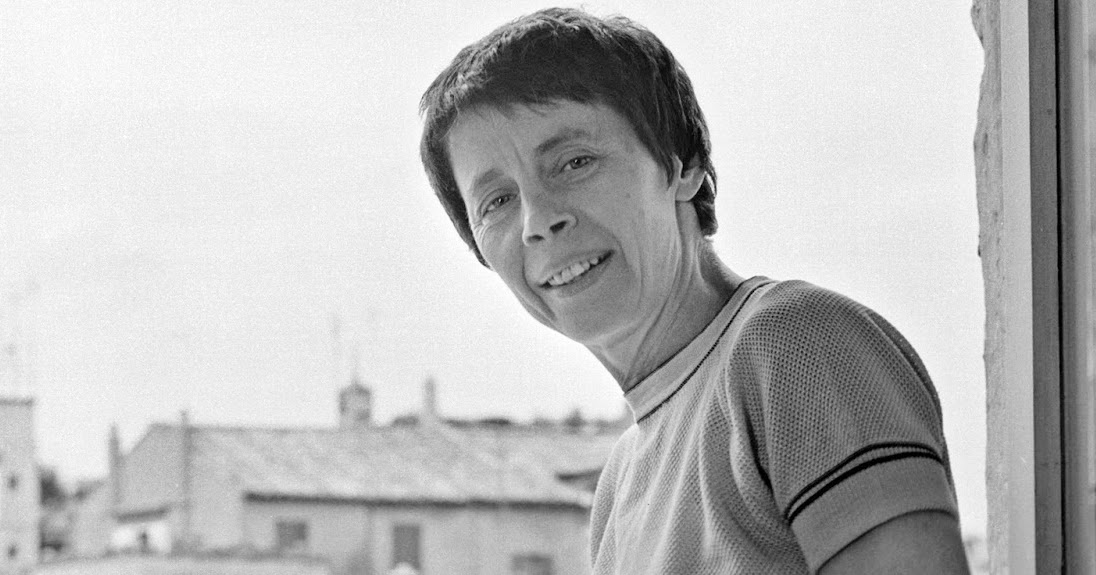

Amelia Rosselli was born in Paris, in 1930, to exiled parents. Her mother, Marion Catherine Cave, was an English activist, and her father, Carlo Rosselli, a noted Italian socialist and leader of the anti-fascist Giustizia e Libertà (Justice and Liberty). In 1937, Carlo and his brother Nello were assassinated under Mussolini’s orders by members of the French fascist Cagoule, a loss that would haunt Amelia for the rest of her life. Following the brothers’ deaths, the remaining Rossellis relocated to Upstate New York, where Amelia Rosselli attended Mamaroneck High. After graduating, she moved to London, and then settled in postwar Rome, where she would spend most of her adult life. Not just a well-respected poet, she was also a translator, musician, and ethnomusicologist. She translated American poets such as Emily Dickinson and Sylvia Plath, and was accepted into the prestigious Darmstadt School, where she collaborated with vanguards like John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen. Repeated hospitalizations plagued her throughout her life, and her alienating experiences of illness and institutionalization informed her peculiar poetics, thematized most overtly in the 1963–65 Serie ospedaliera (Hospital Series) but present in all her work. On February 11, 1996, at the age of 66, Rosselli leapt from the window of her fifth-floor Rome apartment, 33 years to the day after Sylvia Plath had stuck her head in a gas oven.

Writing a concise introduction to Rosselli is a challenge because one is forced to negotiate the truisms that have been parroted to no end—the schizophrenia diagnosis, the hospitalizations, the critical-biographical connections to Plath—alongside the sharp rebukes that Rosselli made of such characterizations throughout her life. She disliked self-pathologizing, claimed she was the target of the CIA’s manipulations, and denounced Plath’s confessionalism as self-involved and incapable of escaping the egoism of the “I.” In a 1963 piece, Pier Paolo Pasolini, a lifelong correspondent with whom Rosselli shared her work, praised her poems, using the Freudian term “lapsus”—a subconscious slip rather than an active choice. Though Pasolini’s discussion of her work was more nuanced, this gendered association between unconscious female genius and Rosselli has, unfortunately, lingered. In the same piece, Pasolini goes on to describe Rosselli as a “sort of stateless person [apolide] from the great familial traditions of Cosmopolis.” Rosselli voiced distaste at Pasolini’s characterization of her poetics as cosmopolitan, noting that cosmopolitanism was a choice, whereas she was a refugee. Discussing Rosselli, we’re often forced to reproduce a good deal of what has been said about her in spite of what she said herself.

Schwabsky’s excellent introduction redirects these narratives. “Rosselli’s is [a] unique […] voice in English,” he notes, “stylistically alone.” However singular she may be, Rosselli, Schwabsky suggests, might be put into more productive conversation with other Anglo-American poets: namely, Mina Loy, Veronica Forrest-Thomson, Anna Mendelssohn, Joyelle McSweeney, and Catherine Wagner.

Rosselli’s interest in the Elizabethans stems from a lifelong experiment with notions of “patria,” or homeland. Born in Paris and raised in New York and London, she nonetheless chose Italian for her language and Rome as her home—signifiers of the nation that executed her father and uncle. Perhaps the defining influence upon Sleep, however, is Shakespeare. Through her strange, pseudo-Renaissance English, Rosselli name-drops Shakespearean characters and plots throughout.

Antiquarian poetics have long belied regressive politick or allegorical critique, or both. Edmund Spenser penned The Faerie Queene (1590) in an archaic English that his own contemporaries found difficult to parse, at once harboring imperialist ambitions through its narration of the founding of the British Empire and casting aspersions on Queen Elizabeth’s reign. In Rosselli’s deft hands, archaic turns of phrase become, as Schwabsky notes in his introduction, a “parodic antiquarianism,” interrogating the concept of “pure” patrimonies in the first place.

Throughout her life, Rosselli described herself as a “poet of research” (“poeta della ricerca”). In observing various forms of meaning-making, she was interested in the intermingling of not only languages but also periods: to read Rosselli is to peel back traditions of canon-spanning verse, from dolce stil novo to Robert Lowell. Thumbing through Sleep, one begins to look at words anew, to think about etymologies and trace historical meanings in order to piece together some semblance of sense.

Take an example from Sleep, which opens: “Fright / Desdemona’s petticure, was all-afrantic he / might come off rushing on the last bus, but / we were ready to admire his creative genius / and let nothing disturb us save the chime at / the door-bell when it rang off at its best.” Assuming that it’s a noun, what is a petticure? The neologism sounds like the English “pedicure,” but the spelling of “petti” indicates otherwise; because of the allusion to Othello, one is tempted to think of a “petticoat,” or even just stop at “petti,” or “petty,” which often implies something diminutive, unimportant, often feminine. If we take “petti” on its own, then we might separate the “cure” as well, from the Latin “cura” for care, or concern. Little concern. Feminine concern? Could this bring us back to the topic of pedicures, perceived as a “feminine concern”? But if we consult our historical dictionaries, “cure” came also to mean during the English Renaissance “office,” what we now know as “treatment,” or even “mistress”; if we telescope back to Rosselli’s postwar world, all these words and their connotations of labor, medicine, and marriage have gendered implications—“the talking cure,” female hysteria, changing social mores about relationships, and so on. We could go on and on. One interpretive choice leads into a net of other associations.

As she composed Sleep, Rosselli claimed she was interested in reimagining the gender politics of the lyric. From Petrarch’s Laura to Donne’s “Mistress Going to Bed,” the lyric has long relied on gendered tropes of discardable, fickle women, what Katie Kadue has described as “lyric misogyny.” Reversing the figure of the male speaker complaining of a female object, Rosselli reconsiders these relations throughout Sleep, reinterpreting this Elizabethan inheritance (itself drawing from the Italians) through a female speaker’s perspective. Though she claimed throughout her life to be uninterested in being known as a “female poet,” Sleep is one of Rosselli’s works that plumb problems of gender most overtly.

In his introduction, Schwabsky suggests that the title of the collection evokes Hamlet’s famous soliloquizing: “To die, to sleep— / No more—and by a sleep to say we end / The heartache, and the thousand natural shocks.” Yet the collection might also call to mind Macbeth’s refrain of “sleep no more”:

Methought I heard a voice cry “Sleep no more!

Macbeth does murder sleep,” the innocent sleep,

Sleep that knits up the ravell’d sleeve of care,

The death of each day’s life, sore labour’s bath,

Balm of hurt minds, great nature’s second course,

Chief nourisher in life’s feast—

Some contextualization is important here: Macbeth’s poeticizing is cut short with his wife’s interjection: “What do you mean?” This description of sleep is interrupted through miscomprehension. This experience of obstructed understanding is thematized, reproduced, throughout Rosselli’s poems. Sleep itself begins with a sort of “awakening,” a murder: “What woke those tender heavy fat hands / said the executioner as the hatchet fell / down upon their bodily stripped souls / fermenting in the dust.” The poems that follow feel interconnected, but nonsequential. Shakespeare is interspersed throughout, whether through vague plots or stock figures (despondent queens, court fictions) or direct allusion (“Otello has taken / the wheel in hand, his / broken fingers icily clasp / the silver pumice”). But I return here to the connection with Othello, which I find most compelling: think of Desdemona and her famous bedtime words, before Othello comes in and smothers her for her (false) betrayal. Again, the associations of death and slumber come rushing forth.

In 1927, just before Rosselli’s birth, the Italian journalist Santi Paladino published an article in the fascist journal L’Impero, claiming that Shakespeare had, in fact, been an Italian man named Michelangelo Florio. In 1929, around the same time that Mussolini’s government began censoring the use of “foreign words” (“parole straniere”), Paladino published the book Shakespeare sarebbe lo pseudonimo di un poeta italiano (“Shakespeare would be the pseudonym of an Italian poet”). I’m not suggesting that Rosselli had in mind Paladino’s version of the Shakespeare question, or was even aware of it. But what Rosselli does with her language games is nonetheless a troubling of purist linguistic patrimonies.

As Scappettone notes, “It is a political act to damage the national language.” In Sleep, Rosselli’s strange English, which draws upon Shakespearean motifs and her career-spanning research into not just different national languages but also the dialects of the working class, and, later in her Documento (1976), the illiterate, reveals the Anglo-English canon as heterogeneous, as made up of geographic and linguistic crossings and histories of colonialism and imperialism. If Paladino wanted to “reveal” the “real” Shakespeare as an Italian through the fascist strategies of factual distortion and fantasies of origins, Rosselli’s Shakespearean experiments reveal patrimonial fictions as always having been migrant and cross-fertilizing.

Rosselli’s poems find affinities with other, wide-ranging attempts at troubling our understanding of linguistic rules. Jonathan Stalling’s Yíngēlìshī (2011) is a similar experiment in global poetics intended “to oppose popular ideas of ‘Chinglish,’” or Chinese-inflected English, as “‘bad’ English.” In the process, he interrogates the often racist and white-supremacist undertones of assuming a “correct” English, something that James Baldwin also meditated upon in his 1979 essay “If Black English Isn’t a Language, Then Tell Me, What Is?” Though their language games are quite different, Rosselli’s Sleep might be placed alongside other projects of dismantling linguistic rules, suggesting that our nativist expectations might need rethinking.