Collateral Damage: Luigi Dallapiccola’s Musical Innovations Between Tyranny and Ideology

Alessandro Cassin

With a riveting concert performance of Luigi Dallapiccola’s Il Prigioniero, Alan Gilbert and the New York Philharmonic have taken a step towards introducing American audiences to one of the forgotten masterpieces of this Italian iconoclastic composer.

To this day not many people on this side of the Atlantic are familiar with Dallapiccola’s work, a composer who made dodecaphonic music palatable to the unconvinced.

During the 1920’s and 30’s music lovers throughout Europe were deeply divided between those who embraced and those who rejected twelve-tone music. Opera audiences in particular were baffled by Alban Berg’s Lulu (1922) and Wozzeck (1937). To many, dodecaphonic music had squeezed out tonality and lyricism, turning it into something cold and cerebral. Among his contemporaries who adopted Arnold Schoenberg’s method of composing, Dallapiccola was unique for his lavish melodic sense. However, trapped in the repressive cultural provincialism of Mussolini’s Italy, Dallpiccola’s contribution to the dodecaphonic debate went unnoticed.

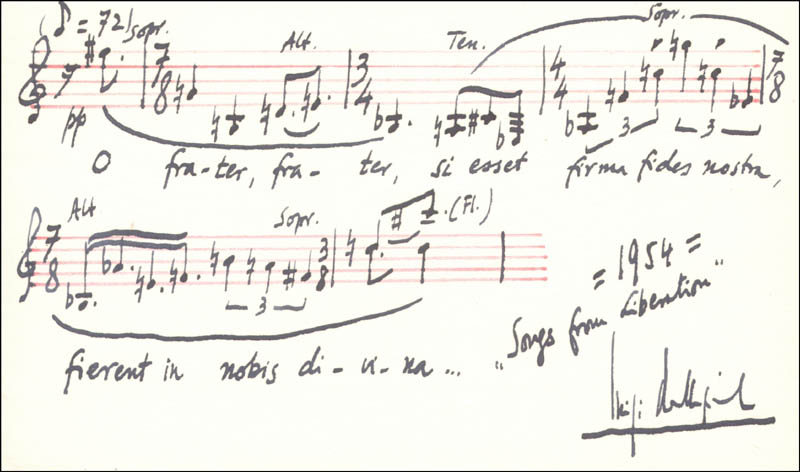

Much of Dallapiccola’s vocal works are wrenching meditations on the physical and psychological cruelty of oppression and imprisonment. Il Prigioniero, composed between 1944-48, about a despairing prisoner during the Spanish Inquisition, can be seen as a metaphor of political injustice throughout human history. This theme had been at the center of Dallapiccola’s thoughts since the 1930’s, as exemplified in his Canti di prigionia (1938-41) – for chorus, two pianos, 2 harps and percussion.

Musicologists and fellow composers have long recognized Dallapiccola’s large musical gifts, but it has been mostly a success d’estime in the eyes of a few. The stifling cultural climate in which he came of age – Mussolini’s Italy – interfered with his creative output and ability to reach international audiences.

Luigi Dallapiccola was born in 1904, the year Alban Berg and Anton Webern joined Arnold Schoenberg in his exploration of atonality. In 1923, one year before Mussolini came to power, Dallapiccola entered the Florence Conservatory. He was the first Italian composer to adopt the dodecaphonic method. While the use of twelve-tone rows had become synonym with atonality, Dallapiccola’s music proved that the method was not incompatible with tonality and in fact he never lost his predilection for the melodic line.

Italy’s cultural establishment was not receptive to Dallapiccola startling innovations and bold lyrical modernist approach. He was denied the kind of international exposure that would have brought him into direct contact with the European avant-guard spearheaded by the Second Viennese School.

Dallapiccola’s work did not have the impact it deserved for a combination of artistic and political reasons. His attempt to blend the Italian tradition of Monteverdi and Gesualdo with Schoenberg’s atonal explorations was clashing with the dominant conservative music taste promoted by the Italian authorities of the time. His oppositional politics further distanced him from the much needed public funding and support.

Canti di Prigionia, for instance, which he set to texts about imprisonment from different ages – a prayer of Mary Stuart, Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy and Savonarola’s Meditation on the Psalm ‘My Hope Is In Thee, O Lord’ – was his musical response to Mussolini’s anti-Jewish legislation. Composed in 1938-41, the first canto premiered on Brussels Radio in 1940, weeks before the Nazi invasion of Belgium.

Living in Florence in the 1920’s and ‘30’s the composer frequented artists and intellectuals of anti-Fascist leanings, without actively participating in political activities: it was through music that he expressed his dissent:

“I would have liked to protest, but I was not so naive as to disregard the fact that, in a totalitarian regime, the individual is powerless. Only by means of music would I be able to express my indignation.”

Mussolini and his entourage had little interest in musical modernism. During the twenty-year Fascist Regime, the only contemporary Italian composer whose work was performed regularly in Italy, as well as in the rest of Europe, was Ottorino Respighi (whose librettist Claudio Guastalla was Jewish). More daring composers were viewed with suspicion: Ildebrando Pizzetti’s compositions were judged “too ascetic”, Gian Francesco Malipiero’s “too eccentric “and Dallapiccola’s mentor Alfredo Casella’s “too cosmopolitan”. The Fascist censorship found that the music of these composers ran against its nationalist, militaristic and conformist aesthetic.

Dallapiccola’s early childhood experiences colored his attitude toward nationalism and political repression. Born in Pisino D’Istria (now Pazin, Croatia) to Italian parents, in what was then part of the Austrian Empire, he witnessed the human cost of shifting borders. When he was only ten years old, his whole family was sent to an internment camp in Graz, after the Austrian authorities began to suspect his father of Italian nationalist leanings. This was a formative experience, leaving no illusions on the fate of political and racial minorities living under an authoritarian regime.

With Mussolini’s advent to power, Dallapiccola had an initial attraction toward Fascism – which had turned into resolute opposition by the late 1920’s. In the 1930’s his vocal protest against the Abyssinian campaign and Italy’s participation in the Spanish Civil War -on Franco’s side- made him a hero among his anti-fascist musical students and a foe for the Regime. He was supporting himself as a concert pianist, while his career as a composer was severely hindered by his political sympathies.

In 1938 the infamous Racial Laws demoted Italian Jews overnight into second-class citizens. Jewish teachers and students were expelled from musical conservatories (as well as from all public schools and universities).

In recent years much has been written about the Italian Jewish composers that had to hide their identity or were forced to emigrate during this period. Mario Castelnuovo–Tedesco moved to Los Angeles, Vittorio Rieti to New York, Renzo Massarani to Rio de Janeiro. Others such as Alberto Gentili, Aronne G.A. Fano and Aldo Finzi remained in Italy but changed their names and went into hiding.

For Jewish composers and musicians things got worse and worse: on June 18th 1940, the government prohibited Jews – even if discriminati (exempted from the racial laws) from taking part in public performances. In April 1942 Jews were banned from all forms of cultural entertainment.

Though not a Jew himself, Luigi Dallapiccola belongs to the larger category of artists and intellectuals whose work was indirectly affected by the Racial Laws. In addition to his anti-Fascist leanings, the composer was married to Laura Luzzatto, who was Jewish. The couple was forced into hiding on two occasions for several months and Dallapiccola’s career was put on hold until after the war.

A cultured man and a voracious reader – in addition to Italian he could read fluently in German, English, French and Spanish – Dallapiccola had a lasting impact on florentine intellectual life, frequenting painters, poets and scholars.

Any temptation he may have had to return to his native Istria, was stunted by the political situation. Not only was anti-Jewish legislation applied there with a zeal unmatched in the rest of the country, it was also the place where the Fascists had begun the first large scale experiment in ethnic cleansing in 20th Century Europe. Italian peasants from the South were being sent to repopulate areas where the Slovene and Croat minorities had been residing for decades. The Italian language and Catholicism were imposed by force and the Slav minorities violently repressed.

After the war and the fall of Fascism, Dallapiccola’s music still did not find its place in Italian culture. In the politically polarized late 1940’s and early 50’s, as the Communists and Christian Democrats were competing in both their political and cultural visions for the country’s future, Dallapiccola refused any party affiliation and found himself isolated once again.

A case in point was the critical reaction to the premiere of Il Prigioniero, performed in Florence in 1950. An allegorical work that could have never been performed during Fascism because of its transparent anti-oppression symbolism, it was met with deep suspicion by some of the critics on either side of the new ideological divide.

The subject was an unnamed totalitarian state, but was it Fascism? Was it Communism? Or was it literally a critique of the Church and the Inquisition? While Communist critics feared it could be read as a criticism of Stalinist Soviet Union, Catholics were disturbed by the possible negative implications on the Church itself as an institution.

These reactions to Il Prigioniero were proof of the ideological projections an allegorical work of art can trigger.

Much as his earlier works were stifled by Fascism, Dallapiccola’s masterpiece ended up as collateral damage of clashing post war ideologies trumping artistic expression. Dallapiccola did not hide his disillusionment with the cultural climate that dominated post-war Italy, and began looking for professional opportunities abroad. None of his post 1950 compositions, except for one, had their premiere in Italy.

While some of his works for piano (the Sonatina Canonica su Capricci di Paganini and the cycle Quaderno Musicale di Annalibera) or the small- scale vocal work Liriche Greche were well received, his major compositions were rarely performed. Dallapiccola became known mainly as a pianist, composition teacher and theoretician. Among his students were Sylvano Bussotti, Abraham Zalman Walker, Bernard Rands, and Luciano Berio.

After the war, largely because of Dallapiccola, Florence (together with Paris) became a major attraction for American composers who wanted to study in Europe. Dallapiccola and his vast cosmopolitan culture seemed to offer continuity with pre-war European avant-guard. His lessons in orchestration in particular had a lasting influence on the American composers in their emphasis on Mahler, whose symphonies he knew intimately. Before Bernstein brought Mahler to the attention of the American public, it was through Dallpiccola that young Americans began their initiation into his music.

In the 1950’s and early 60’s he traveled often to the United States. For a moment it seemed that in the US Dallapiccola could reach the international recognition he deserved. His music was performed to rave reviews at Tanglewood in the summers of 1951 and 1952. Beginning in 1956, he was hired to teach composition at Queens College, New York. In 1954 the New York Philharmonic performed his Symphonic Fragments from the ballet Marsia. The New York Times critic Olin Dowes wrote:” Mr. Dallapiccola is commonly ranked among the atonalists, but atonalism as he employs it is not the dominant characteristic… The counterpoint sings in a melodic manner, and often leads to harmonies and orchestral colors that have identity in themselves”. On that occasion the Philharmonic was conducted by Guido Cantelli, Toscanini’s protégé, who was destined to become the orchestra’s Music Director. Cantelli ranked Dallapiccola among the major living European composers and would very likely had championed his work further, had he not died tragically in a plane crash in 1956 at the age of 36.

By the mid’ 1960’s the musical world’s attention had moved past serialism, and Dallapiccola’s work had not been included in the standard dodecaphonic repertoire. His 1968 his opera Ulisse marked the apex of his career, after which his output was sparse. Back in Florence, he spent his later years writing essays rather than music. Because of his failing health he gave up composing in 1972 and died of lung disease in 1975.

Today, Gerard Mortier, Lothar Zagrosek, Alan Gilbert, Leon Botstein, Esa-Pekka Salonen and Gian Andrea Noseda are among those who are actively promoting Dallapiccola’s work.

But can audiences truly appreciate his musical innovations 60- 70 years later, when debates over dodecaphonic music have become mere academic pursuits? The dramatic intensity of his music can certainly still serve well the timeless theme of human freedom and subjection.

Yet belated recognition cannot compensate for what coming of age in Fascist Italy took from him personally and artistically.