Emanuele Trevi is an Italian writer and literary critic. His book on the poet Pietro Tripodo won the Sandro Onofri Prize. In addition to. many novels and critical essays in 2007 he published Invasioni controllate, an insightful and touching book length interview with his father, the Jungian psychologist Mario Trevi He was creative director of the publisher Fazi. Trevi has served on the jury for several literary awards and has written for magazines and various national newspapers, including La Repubblica, La Stampa, and Il Manifesto. In 2012, he won the European Literature Prize for Something Written, on his experience of working at the Pasolini archive, is his only novel available in English (World Editions International, 2016.) His work has been translated into more than 10 languages.

Alessandro Cassin is the director of Centro Primo Levi’s online magazine, Printed Matter and CPL Editions which published over 13 books since its debut in 2014. Coming from a tradition of publishing —his father published the first edition of If This Is A Man in English—Cassin began working in experimental theater and was awarded the Premio Ruggero Rimini 1989 for Il Presidente Schreber. He has been a cultural reporter for publications including L’Espresso and Diario. He is a contributor of The Brooklyn Rail. His book Whispers: Ulay on Ulay co-authored with Maria Rus Bojan received the 2015 AICA Netherlands Award. He coordinated the publication of Laurence Butch Morris’ The Art of Conduction edited by Daniela Veronesi (Karma, 2017)

Due vite (Two Lives) by Emanuele Trevi is a luminous, beautifully written wisdom book. It was deservedly awarded the 2021 Premio Strega, Italy’s major literary prize, and awaits the foresight of an American publisher for an English translation. An accomplished literary critic, ever since I cani del nulla (Einaudi 2003), his debut novel, Trevi, has been honing a personal narrative style, where real-life experiences fuel the world of the imagination.

Due vite is the double “literary portrait” in which the lives and work of two authors, Pia Pera and Rocco Carbone, who died prematurely, is recounted in the light of their intense friendship with Emanuele Trevi. True friendships are necessarily few because there are few people with whom we can afford to bear our true face without wearing our countless social masks. Full of introspection yet devoid of any self-indulgence, the book weaves together slices of real-life with important reflections on existence, restlessness, pain, and youthful joy. Though the book’s themes are timeless and universal, reading this work during the current pandemic underlines the urgency of reflecting the value of friendship and keeping alive the memory of prematurely departed loved ones. Trevi’s prose has the power to dig inside, drag us into whirlpools of thought, open wider horizons while reaffirming the richness of the life of the mind.

Alessandro Cassin: It seems to me that defining Due Vite (Two Lives) —and perhaps any of your books— “a novel” may be misleading. Over the years, the main feature you have refined is an interest and a technique for the “literary portrait.”

In your books, you have created portraits of Rome, specific space and times, texts, and above all, of people. Can we talk about this “technique”?

Emanuele Trevi: I agree, the word “novel” has lost any objective meaning, at least for me … yet if publishers use it for my books, I don’t object, far from it! What interests me, if anything, is to create “verbal equivalents” of the lived experience: people, places, works of art. For this reason, criticism has always been my primary vocation, my most significant source of satisfaction. I consider my books to be essays made as interesting and accessible as possible by the absence of technicalities and by the inclusion of a narrative trend. But I am certainly not the inventor of this hybrid genre! One could say that it was Montaigne who started this, but also Plutarch’s texts, in this respect, still read as modern today!

AC: A portrait presupposes one (or more) portrayed objects and one or more observers. Further, the observation distance and the relationship between subject and observer. To give a few examples, in Something Written (2012), you create a sort of “portrait “of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Petrolio di PPP, an anomalous literary text, something between a novel and an essay which in certain aspects resembles your own books. Despite your work at the Pasolini Fund and your description of the exasperating and hilarious relationship with Pasolini’s “guardian,” Laura Betti, it is a portrait from a distance: you had not met Pasolini in person. In Sogni e favole (Dreams and Fables (2019), the distance is reduced. Arturo Patten, Amelia Rosselli, and Cesare Garboli are people you met, and towards whom you had strong feelings. Finally, the portraits in Due vite, those of Pia Pera and Rocco Carbone, the subjects are your friends, your fellow travelers in life, people with whom you had built a sense of “we”. By reducing the distance from its subjects, the narrator gradually reveals himself more. In Sogni e Favole the narrator observes and narrates; in Due Vite, he exposes more of his thoughts and feelings. The book deals with the friendship between three people, one of whom recounts after the departure of the two main characters.

ET: Each portrait has a separate story. Sometimes you have to stay closer to the subject; now and then, you must step back. The most dangerous thing about writing is that our unconscious always compels us to repeat what has been successful in the past, thus locking or paralyzing us in formulas that do not always work for everything. The shadow with which I and many of my contemporaries deliberately “muck up” the shot must never be identical to itself. The feeling of narcissism or self-referentiality, the most widespread criticism of this type of writing, depends not on speaking of oneself but on speaking of a self that always remains identical to itself. Instead, the narrative I must always be a mobile presence, with a capacity to shift, particularly, I would say, within the same book.

AC: I don’t like the term “self-fiction,” yet it may help explain one of the substantial differences between a traditional novel and your books: the contrast between fictional characters and characters taken from real life. While novels have accustomed us to fictional characters, yours, in contrast, seem to emerge from the encounter between real life and imagination. Can you talk about this difference and the inevitable overlaps?

ET: In the act of writing, I am producing a device intended to be completed and made functional in the mind of a reader who does not know my real characters and places any more than he knows Harry Potter or the world of Oz, so all these distinctions do not have great practical significance. I speak as a reader: what value can it have for me that Karl Ove Knausgaard’s father really existed? Things become more interesting if we consider psychological assumptions: I am quite devoid of what we commonly define as fantasy. I appreciate it in others, I am a passionate reader of fantasy literature, but I don’t know how to invent. I only know how to manipulate the data that come to me from experience. It is quite understandable that distinctions are created between writers based on attitudes that have little relevance in literary creation. Still, we must never forget that even experience is a convention, like any other grammar of invention.

AC: There is an aspect of your books that, in addition to impressing me deeply, fills a gap. The two of us are peers; in the course of our lives, at some point, we stopped writing and receiving letters. Receiving a letter meant moving our eyes across a text specifically written for us. Your book seems to address, intimately and directly, the reader, as if it were written just for him. This feels like magic! It is a kind of prose that has minimized any impersonal element and distills the communication between the writer and the reader. Do you have a recipient in mind when you write?

ET: No, or at least I never noticed.

I always think of an abstract reader who knows nothing of what I am writing about from other sources: this seems to me an optimal condition.

AC: The subjects of your portrait are two complex and intriguing personalities and the larger theme of friendship, made of elective affinities, complicity, misunderstandings, concurrent times, and out-of-phase times. Your narrator is not a static figure. He takes note of the inevitable changes, even profound ones, in the lives of his friends.

It is impossible to say with certainty that Pia and Rocco would be happy with your book, but surely you have given them the gift, making them live again for the reader. I wonder how and if your relationship with them has been renewed or transformed by the act of writing?

ET: We don’t write what we had thought about before. Rather, we think while writing, so one never finishes a book the same as one has started it. I always understood how I felt about the people I wrote about, only when I was finished.

AC: Let’s go back to the epistolary aspect. At times the book reads like a letter from you to Pia and Rocco, in others a letter about them to the reader, and yet in others, a refined spontaneous form of three-way conversation. The postal service between the world of the living and the world of the dead is notoriously not working well, yet the reader feels a real communication between you. By writing about them, you keep them temporarily alive. (A further magic!) The characters of your book are no longer in the real world but in the space of imagination and memory. Would you have known how and wanted to write about them while they were still living?

ET: I actually di happen to write about both Rocco and Pia’s work because I’m a literary critic, and they wrote books. But the dead lack a future, at least in this dimension of reality, which is decisive from a narrative point of view.

AC: Among other things, you are a literary critic. Thus, you move from describing their lives to portraying their works critically with great ease. What’s more, you found the tone —so rare in contemporary criticism— of someone “implicated” in the work about which he is writing. Yet, you maintain the necessary detachment. There are your feelings for Rocco and Pia, your gaze on their lives, as well as a critical reflection on their work. The result is an invitation to read and rediscover these two author-friends of yours.

ET: Yes, but I hate the so-called “science of literature,” I always find an emotional bond; I describe the experience of reading more than the text itself. But, of course, in a 5,000 characters article, all this is embryonic. Still, even there, I can create tiny slips between the book and the lived experience: sometimes, all you need is an unexpected adjective or an off-centered observation.

AC: The strength of your portraits and self-portraits, for me, is in the awareness that each of us is singular, unrepeatable, and uniquely contradictory. Speaking of Pia (but it applies to all your characters), you write: “How is it possible that we contain so many disharmonious and unpaired things within us.” Rocco and Pia and their narrator fascinate the reader above for their contradictions. Of Rocco, you write: “The more you repeat a word, the more it becomes the equivalent of its opposite. As if repetition revealed the trick, reminding us that there is no adequate word for the indecipherable mess of human life in its perennial failure.”

ET: Two opposite realities determine our perception of the human: on the one hand, we are alike, otherwise, we would not be interested in any character from literature or cinema. On the other hand, the individual configuration of our destiny is unique and unrepeatable. We are a bit like the proverbial snowflakes: looking at them under the microscope, no two of them are alike.

AC: In the Jewish tradition, a limmud is a text written in honor of a person who has left, an attempt to go beyond the hagiographic rhetoric and focus on the intrinsic teaching of that person’s life (literally limmud comes from the verb to learn/to teach). I read your book as if it were a limmud. “… We live two lives, both destined to end: the first is the physical life, made up of blood and breath, the second is the one that takes place in the mind of those who loved us. And when even the last person who knew us closely dies, well, then we really dissolve, we evaporate, and the great interminable party of Nothingness begins, where the stings from what we lack no longer sting anyone” [my translation]

ET: Your question prompted me to think of some compelling examples of limmud (I didn’t know this word) in contemporary literature. And I was reminded of Saul Bellow – not surprisingly, a great Jewish write and his novel Ravelstein. Also, in this case of the intrinsic teachings of a life, I would say, lays not in the virtues nor the achievements, but in the strength of character, the manner in which the individual relates to “the negative,” not necessarily to difficulties, but to the very fact of being mortal and thus subject to the unpredictable.

AC: Your books often trace walks or physical or mental journeys, the traveling of a distance, rather than reaching a goal … In the case of your latest book, the narrative seems to define an arc: did you know its trajectory beforehand?

ET: I had an idea: to return, after so many years and in the form of a crumpled postcard to an image: The Origin of the World by Courbet. At the beginning of the book, Rocco and Pia and I see the painting at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. On the last page, I see the postcard stuck in the glass of a sideboard in Pia’s living room in Lucca, but I don’t dare to remind her of that beautiful morning of our youth. So more than an arc, it is an actual circle that closes.

AC: In evoking your two friends, deep emotion shines through, as well as the things you admired in them and those around which you clashed. All without a shadow of sentimentality. How did you find that extraordinary balance between emotion and sobriety?

ET: I believe that there is a form of irony —neither cold nor cynical— based on the feeling of imperfection and approximation with which we live our life. I don’t like moral postures, and I don’t like virtue; the only thing I believe in is involuntary, instinctual “good.” For this reason, I believe that political correctness, in all its forms, is a cultural calamity whose consequences we still have to measure. We are handing over the world of artistic expression to a minority of conformist idiots, mediocre people, as during McCarthyism. It is not censorship that worries me, but self-censorship.

AC: Speaking of Rocco Carbone’s writing, you define it as “art prose,” a term Luca Mastrantonio attributes in the back cover blurb to your own writing. Do you recognize yourself in this term, and more generally, do you want to say something about your style?

ET: I believe that the history of Italian poetry metrics, particularly of that extraordinary instrument that is the hendecasyllable, today has more prominence in prose than in poetry. So, when rewriting, I pay a lot of attention to sound. I also sacrifice some element of meaning to the music of the words, create caesuras, and so on. I would say that the most reliable meaning of “art prose” is that of getting paying attention to these things: you end up writing everything a bit musically as a way to simplify and condense, even a newspaper article.

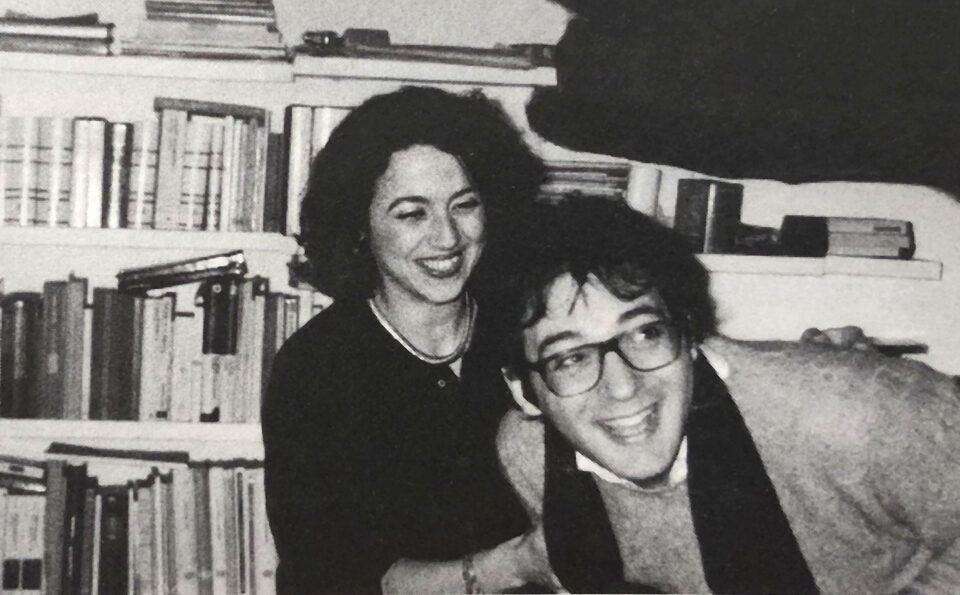

Image: Pia Pera and Emanuele Trevi, Photo By Rocco Carbone