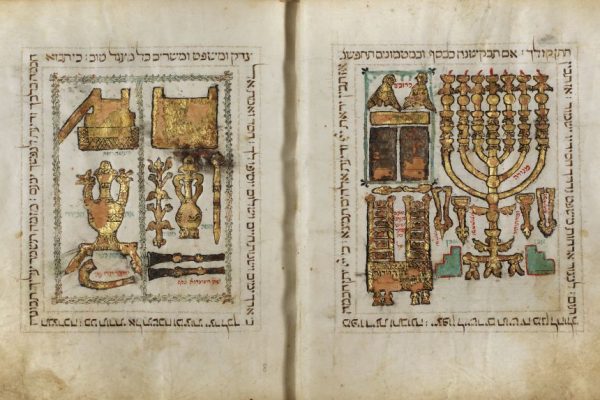

Salvatore Garau, Daniel Tilles, Fascism and the Jews: Italy and Britain, Vallentine Mitchell, 2011

Franklin Adler. Review of Garau, Salvatore; Tilles, Daniel, eds., Fascism and the Jews: Italy and Britain. H-Judaic, H-Net Reviews. March, 2012. H-Judaic, March 2012

This volume is a collection of papers presented at conference of the same title at the University of London in late 2008. Typically, in such a format, the separate essays are uneven and do not add up to a coherent whole, though all are certainly interesting. The young editors (Daniel Tilles and Salvatore Garau) emphasize the importance of a comparative approach, though none of the essays rigorously compare the Italian and British cases, leading to some confusion until the reader discerns that by “comparison” they rather have in mind how, and to what extent, these separate cases conform to a general model of fascism (never fully specified, beyond such loose familiar terms as a “fascist minimum” and “generic fascism”). British scholars of fascism–some, not all–tend to have greater confidence in such a general model or framework than their counterparts in Europe and the United States, where recent studies by proponents of a general model of fascism, such as Michael Mann, have met with some measure of criticism.[1] All that notwithstanding, the editors certainly are correct in maintaining that the extreme nationalism manifest in all instances of fascism led to targeting of some racial, religious, or ethnic “other,” more often than not Jews.

The editors also rightly emphasize the need to decenter Germany as the presumptive modal type of fascism, as well as the universality of its distinctive brand of anti-Semitism. There are two important reasons for doing so. First, while it is true that by the second half of the 1930s, Germany began to eclipse Italy as the ascendant fascist leader, there were domestic reasons for “othering” Jews that emerged from divergent, localized national conditions, quite separate and distinct from some grandiose idea of a Nazi program writ large. In fact, this confluence of a general tendency toward diabolizing others and diverse local patterns of anti-Semitism in Europe is astutely analyzed in a particularly insightful essay by Aristotle Kallis. Second, there was a tendency, after the war and the horrific revelations of the Shoah, manifest among those who collaborated with the Nazis to blame the “bad Germans” subsequently for all the evils visited upon their Jewish compatriots, thereby immunizing themselves against any direct culpability for their own particular anti-Semitic policies. And in no country was this auto-exculpatory stance more pronounced than in Italy, where the myth of the “good Italian” (italiani brava gente) reassured the population, quite falsely as we know now, that the anti-Semitic measures of 1938, if they were discussed at all, were the result of pressure from Germany and never fully implemented, while the virtuous Italians did all they could to protect their Jews from the bestial German occupiers, after Mussolini fell from power in 1943.

As the editors reiterate often in their introduction, in both Italy and Britain fascist movements initially were not programmatically anti-Semitic, as was the case in Germany, but became so only during the second half of the 1930s. In the case of Britain, this racist turn mainly reflected Nazi Germany’s displacement of Fascist Italy, both as a model to emulate and a source of external funding. The evolution of anti-Semitism in Fascist Italy is far more complex, and has generated a substantial amount of research during the past twenty years in particular, stimulated largely by the critical work of Michele Sarfatti. Compared to the earlier research of Renzo De Felice and Meir Michelis, Sarfatti demonstrated that Fascist anti-Semitism was not the simple consequence of Italy’s growing diplomatic ties with Nazi Germany, but emerged quite independently, due to factors internal to Mussolini’s regime. Moreover, Sarfatti demonstrated that Italy’s anti-Semitic legislation was fully and rigorously implemented, in the face of popular collaboration and general indifference, stripping Italian Jews of their citizen rights, material standing, and prominence in the world of business and especially in the professions.

Salvatore Garau contributes the volume’s principal essay dealing with the emergence and consolidation of anti-Semitism in Fascist Italy. Substantively, it well reflects the recent work of of Sarfatti and others, largely unknown outside Italy. Garau focuses on two anti-Semitic sources, the Roman Catholic Church and Italian nationalists. The record is a bit more complicated than Garru suggests, particularly the role of the Vatican. Recent research, conducted after the archives of Pius XI were made accessible, demonstrates the fierce opposition of Pius XI to the racist turn of the regime in general, and to the 1938 anti-Semitic legislation, in particular, which violated the terms of the 1929 Concordat, flew in the face of Catholic universalism, and undercut the familial status of Catholics who had intermarried with Jews, as well as Jews who had converted. In fact, the clash between Pius XI and Fascism had been so great that the pope’s newspaper Osservatore Romano was suppressed and the pope himself viciously attacked in the Fascist press. The Vatican’s frontal opposition to state anti-Semitism would only be reversed when Pius XI died and Pius XII embarked on a radically different course. Nationalism certainly was a source of anti-Semitism, but it had not been a significant force until the mid-thirties, sixteen years into the regime, when Mussolini’s populist programs (andare verso il popolo) had gone into crisis and Mussolini charted an imperial course with the conquest of Ethiopia, recycling a standard nationalist theme, Italy as a proletarian nation at war with the plutocratic ones. Why then did Mussolini embark on a campaign against the Jews in 1938? In Garrau’s account, there were two proximate causes: the growing importance of Germany and supplementing domestically the racial legislation against blacks that already had been effectuated in Ethiopia. Certainly both are relevant, but Garau never mentions a factor, dealt with by Ilaria Pavan in another essay, that has become increasingly emphasized in recent research: the antiborghese (anti-bourgeois) campaign and Mussolini’s purported anthropological revolution through which a new historical subject was to be created, New Fascist Man. In fact, Mussolini officially initiated the attack against Jews as one of his three so-called belly punches to the bourgeoisie, now denounced as the primary obstacle to the development of a revolutionary new, imperious, proletarian Italy. Accordingly, Jews were attacked, not because of blood and chromosomes, but because they incarnated the new class enemy.

Surprisingly, there is no comparable single essay on the evolution of fascist anti-Semitism in Britain. Instead, there is an essay on Ezra Pound by Matthew Feldman, an essay on attitudes towards Jews in the fascist and mainstream Tory press by Janet Dack, and an essay on Captain Robert Gordon-Canning by Graham Macklin. The latter should be of particular interest for those following a proliferation of new research interest on relations between European fascist movements and Islamist movements in the Middle East, especially concerning Palestine.

Beyond focusing on the evolution of fascist anti-Semitism in Italy and Britain, a second comparative theme is the response of Jewish communities in the two cases. On Italian Jews, there are two essays by Ilaria Pavan and Elena Mazzini. Though a young scholar, Pavan has emerged as one of the most important Italian historians dealing with Jews during the Fascist period, known initially for a book and several papers on the economic consequences of the racial legislation, then a book on the Jewish Fascist mayor of Ferrara, Renzo Ravenna, followed by essays on a host of other subjects. The heart of her essay here is how a new Catholicized, racialized concept of national identity began to evolve after the Concordat of 1929, and entered into the penal code in 1930, some seven years before racism itself became a major ideological theme. This is a topic she has developed in several articles published recently in Italian, appearing here for the first time in English. Almost as important is the consummate erudition with which Pavan frames this topic, presenting the latest research on contested facts and interpretations. The shock and disillusion of a well-integrated Jewish community, one that never saw itself as different from other Italians, is a theme dealt with by Mazzini as well. Through an examination of the Jewish press, she deals with reactions to the 1938 anti-Semitic legislation, as well as how the Jewish and Italian components of their identities were rearticulated.

By way of comparison, the situation of British Jews was significantly different, as no fascist regime had come to power and Jews were free to contest fascist provocations openly and occasionally violently.

Unlike Britain (and Austria, Germany, and France), Italy never experienced the wave of East European Jewish migration that began in the late nineteenth century, engendering anti-Semitic responses long before the fascist era. Amazingly, this important difference is never brought to the reader’s attention or even noted in passing by the editors, despite their rhetorical stress on comparison. London’s East End became a target of fascist action during the mid-thirties because of its concentration of East European Jews, more proletarian, viscerally anti-fascist, and inclined to left-wing politics than the assimilated Jews who dominated national Jewish organizations and had ties to the mainstream political parties. The book concludes with a fine essay by Nigel Copsey and Daniel Tilles, focusing on patterns of cleavage and cooperation between these diverse Jewish communities.

Note

[1].Though Stanley Payne and Robert Paxton wrote comparative histories of fascism recently, both expressed skepticism over a generic definition, model, or concept. Because of the diversity of fascist movements, and the considerable symbolic mimicry and ideological bricolage in Europe after Mussolini’s success, it is often difficult to differentiate between what was substantive and what was superficially borrowed, especially because there never was a definitive seminal doctrinal source or common program that defined and unified fascism. Some of these issues, and a critique of Michael Mann’s Fascists (Cambrdige: Cambridge University Press, 2004), can be found in my review essay in Comparative Political Studies 38, no. 6 (August 2005): 731-736.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.