Every so often, at night, the air-raid alarm sirens would resound through the city; but the people of San Lorenzo paid little attention to them, convinced that Rome would never be hit, thanks to the protection of the Pope, who in fact was nicknamed the Capital’s ack-ack. The first times, Ida, in agitation, had tried to waken Nino; but he would wriggle down in his cot, grumbling: “Who is it? . . . who is it? I’m asleep!” and one night, half-asleep, he mumbled something about a band with a saxophone and drums.

The next day he asked if there had been an alarm, complaining that Ida had spoiled his dream. And he told her, definitively, not to disturb her again when the siren went:

“What do we care about the sirens anyway? Say, má, can’t you see nothing ever happens here? English bombs! Yeah, made out of paper!”

Later she also stopped getting up at the sound of the alarm, barely shifting, half awake, beneath the sweat-damp sheets, amid the screams of the sirens and the firing if the aircraft in the distance.

One night, shortly before an alarm, she dreamed she was looking for a hospital, to give birth. But all rejected her as a Jew, saying she should go to the Jewish hospital, a pointing out a very white cement building, all walls up, with no windows or doors.

Fragment II

Not even from her mother had she ever heard this denomination “Aryans”; in fact the denomination of Jews itself, for little Iduzza in the house down in Cosenza had remained an object of great mystery. Except by Nora, in her secret councils it was never uttered in vain in the Ramundo home!

I have learned that once, in one of his great anarchist perorations, Giuseppe happened to proclaim, in a thundering voice: “The day will come when masters and proletarians, black and white, mail and female, Jews and Christians, will be all equal, in the sole honor of being part of humanity!!”But at that shouted word Jews, Nora let out a cry of freight and blanched as if seized, by a serious illness; whereupon Giuseppe, all repentant, came to her and repeated, this time in a very low voice: “… I said, Jews and Christians…”. As if by whispering the word very softly after having shouted it very loud, he were repairing the disaster!

In any case, now, Ida learned that the Jews were different, not only because they were Jews but also because they were non-Aryans. And who were the Aryans? To Iduzza this term used by the Authorities suggested something ancient and lofty, on the order of Baron or Count. And in her concept, the Jews were opposed to the Aryans, much as the plebeians to the patricians (she had studied history!).

However, obviously, the non-Aryans, for the Authorities, were the most plebeians of the plebeians! For example, the baker’s apprentice, plebeian by class, compared to a Jew was as good as a patrician, because he was Aryan! And if, in the social order, the plebeians were already like scabies, the plebeians of the plebeians must have been leprosy!

Fragment III

“Signora Di Segni was there, running back and forth on the open platform, her legs without stockings, short and thin, of an unhealthy whiteness and her mid-season dust-coat flying behind her shapeless body. She was running clumsily the whole length of the row of cars, shouting in an almost obscene voice: Settimio! Settimio!…Graziella!… Manuele!… Settimio!… Settimio! Esterina!… Manuele!… Angelino!…”

From inside the train, some unknown voices reached her, shouting at her to go away: otherwise they would take her too, when they come back in a little while. “No-o-o! I won’t go!” she railed in reply threatening and enraged hammering her fists against the cars (my family’s in there! Call them! Di Segni! The Di Segni family!” … “Settimiooo!!!” she first our suddenly, running, her arms out towards one of the cars and clinging to the var of the door, in an impossible attempt to force it. Behind the grille, up above, a little head had appeared, an old man’s. His eye glasses could be seen glistering over his emaciated nose, against the darkness behind; his tiny hands clutched the bars.

“Settimio!!” the others?! are they with you?”

“Go away, Celeste” her husband said to her. “Go away, I tell you: right now. They’ll be back any minute …” Ida recognized his slow sententious voice. It was the same that, on other occasions, in his cubbyhole full of old junk, had said to her, for example, with sage and pondered judgement, “This, Signora, isn’t even worth the cost of mending…” or else, “I can give you six lire for the whole lot …” but today he sounded toneless, alien, as if from an atrocious paradise beyond all access.

The interior of the cars, scorched by the lingering summer sun, continue to reecho with that incessant sound. In its disorder, baby’s cry overlapped with quarrels, ritual chanting, meaningless mumbles, senile voices calling from mother; others that conversed, aside, almost ceremonious, and others, that were even giggling. And at times, over all this, sterile, bloodcurdling screens rose; or others, of a bestial physicality exclaiming elementary words like “water!” “air!” From one of the last cars dominating all the other voices, a young woman would burst out, at intervals, with compulsive piercing shrieks, typical of labor pains.

And Ida recognized this confused chorus. No less than the Signora’s almost indecent screams and old Di Segni’s sententious tones, all this wretched human sound from the cars caught her in a heart-rending sweetness, because of a constant memory that didn’t return to her from known time, but from some other channel: from the same place as her father little Calabrian songs, that had lulled her, or the anonymous poem of the previous night, or the little kisses that whispered carina, carina to her. It was a place of repose that drew her down, into the promiscuous den, of a single, endless family.

Fragment IV

Along the wall of the stairs, pealing and covered with stains, you can read various writings, most of them obviously by childish hands :

Arnaldo loves Sara—Ferruccio is handsome (and below, added by another young hand: he’s a shit)—Colomba loves L.—Roma’s the winner.

Frowning, Ida examined all the writings, in an effort to decipher her own confused reasoning in them. The house had two upper stories in all, but the stairway seemed very long to her. Finally, at the next landing, she discovered what she was looking for. Actually, the number of people named EFRATI in the Rome Ghetto, was beyond counting. There was no stairway, you might say where one wasn’t to be found.

Here there were three doors. One, without a name and off its hinges, opened into a windowless cubbyhole, with a springs of a bed on the floor and a basin, both battered. The other two doors were closed. On one, there was a little plate with a name: Di Cave and above it, written on the wood, also the names: Pavoncello, Calò. And on the second, a broad piece of paper was glued, which said: Sonnino, EFRATI, Della Seta.

In her wariness, Ida couldn’t resist the temptation to sit down on those iron springs. From the broken window over the stairs came a swallow’s shriek and she was amazed by it. Heedless of the air raids and explosions, the little creature had flown across the sky—it’s fragile body unerringly oriented—as on a domestic path. While she, a woman, and over forty years old, found herself lost.

She had to make an enormous effort not to give way to her desire to stretch out on those springs and spend the whole night there. And certainly it was this effort which, in her state of extreme weakness, then provoked an auditory illusion. First she was surprised by an unreal silence in the place. And within this, her ears, buzzing for her fasts, began to perceive some voices. It was not, actually, a true hallucination, because Ida realized that the manufactory of those voices was in her brain indeed she herself did not sense them elsewhere. However, the impression she received from them was that they were spreading through her auditory canals from some unspecified dimension, which no longer belong to exterior space, or to her memories. They were alien voices, of various tones, but predominantly female, unconnected with one another, without dialogue or communication among themselves. And they distinctly pronounced phrases, some exclamatory, some relaxed, but all of ordinary banality, like assembled fragments of a common life of every day:

“… I am on the roof collecting the laundry!!” … “If you don’t finish your homework, you are not leaving this house!” … “I’m going to tell your father when he gets home!” … “They’re distributing cigarettes today …” “All right, I’ll wait for you but hurry…” “where’ve you been all this time? …” “…I’ll be right there mà…!” “How much are you asking?” “He told me to start dinner …” “Put that light out; electricity costs money …”

This phenomenon of hearing voices is fairly common and at times even the healthy experience it, more frequently when they are about to fall asleep, and after a hard day’s work. For Ida, it wasn’t new; but in her present emotional fragility it seized her like an invasion. The voices in her ears, before dying away, started reechoing one after the other overlapping at a turbulent rhythm.

And in this haste of theirs she seemed to sense a horrible meaning, as if their poor gossips were exhumed from one confused eternity into another confused eternity. Without knowing what she was saying, or why, Ida found herself murmuring, to herself, her chin trembling like that of a child about to cry:

“They are all dead”.

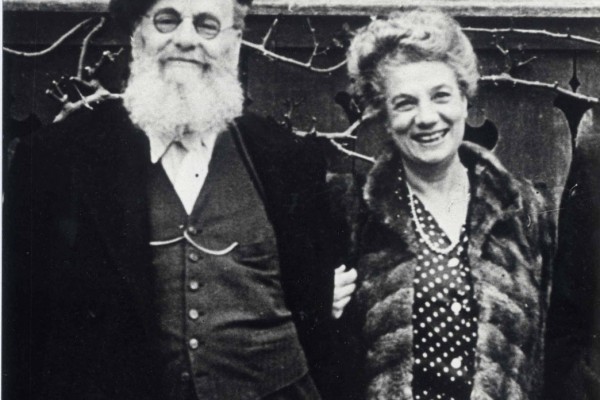

Image: displaced people in Rome, 1943-44

CPL Narratives, by Alessandro Cassin