Eight months after its opening, Bookhouse is flourishing, attracting visitors, students, and scholars. What sets Bookhouse apart is its collaborative nature — Centro Primo Levi, American Sephardi Federation, and Dan Wyman Books — as well as its programming of public events, intimate size, and, last but not least, its salon-like physical appearance. The furniture, rugs (from all over the Middle East), artworks, objects, and books —most of them gifts, found or repurposed —make it a home and a work in progress, inviting everyone to contribute to its evolution.

Recently, we were honored to receive as a gift a table designed and signed by the Italian-born architect Giorgio Cavaglieri. This relatively small 20″ x 40″ x 30″ wooden console table, with its minimalist design and harmonious proportions, exudes a beauty that transcends time.

There is something elemental about this table: at once modern and ancient, it invites us to connect with history while embracing innovation.

The word “table” in English originates from the Latin “tabula,” meaning “plank” or “tablet.” It was adopted into Old English as “tabele” and then evolved through Middle English as “table,” influenced by Old French. A very old word for one of mankind’s first and most basic articles of furniture, together with beds and stools. Tables have been used since at least the 7th century BCE and consisted of a flat slab of stone, metal, and wood supported by trestles, legs, or a pillar. Egyptian tables were made of wood, Assyrian tables of metal, and Greek ones, usually of bronze.

We received that table from the artist Fulvio Testa, a friend of Cavaglieri, who told me that the table was once placed at the entrance of Giorgio Cavaglieri’s home on the Upper West Side.

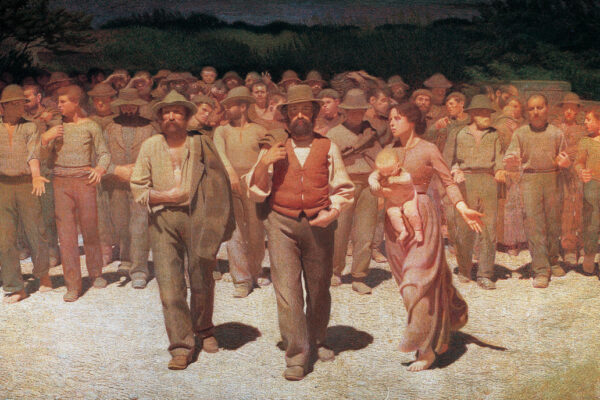

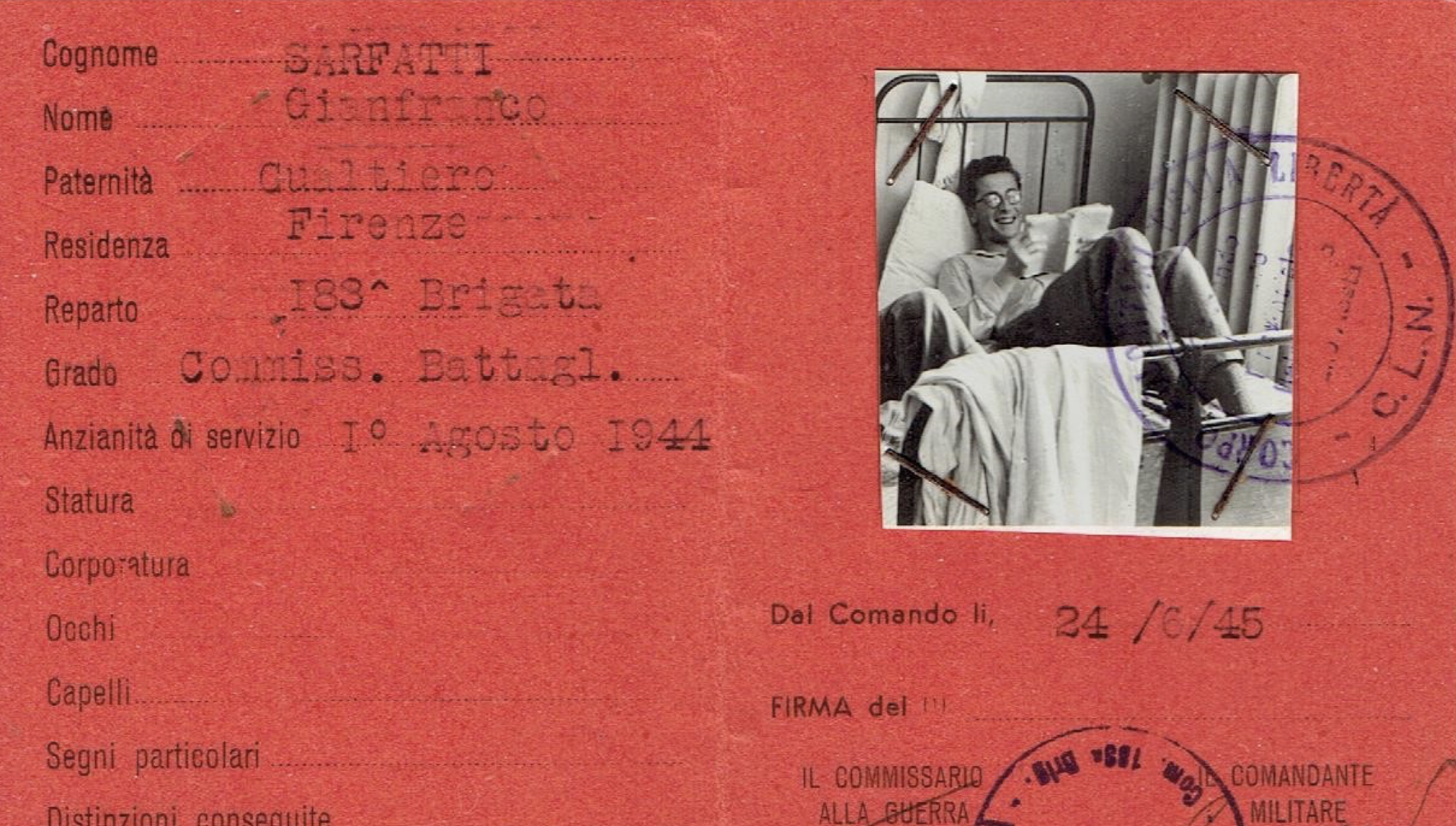

From its inception, Centro Primo Levi has had an ongoing research project on the lives and legacies of the roughly 200 Jewish families that arrived in New York from Italy, escaping Mussolini’s Racial Laws of 1938. This project, which Giorgio Cavaglieri’s story is a part of, aims at preserving and sharing the rich history of these families and their contributions to New York’s and the US’s cultural landscape. Further, the architect attended our first events and frequently visited Centro Primo Levi, leaving us a manuscript of his life memories.

Mr. Cavaglieri was born into an Italian-Jewish family in Venice in 1911. He graduated from Milan’s prestigious Politecnico and soon after found employment as an in-house architect at Assicurazioni Generali, an insurance giant founded by Italian Jews in 1930, which became the leading insurer of the Austro-Hungarian empire. He was drafted into the Italian Air Force at the time of Italy’s Invasion of Ethiopia and designed airfields in Libya for the Italian government. In 1939, following the promulgation of the Racial Laws and the seizure of his family’s assets, he fled to the United States. He first settled in Baltimore, where, in 1942, he married Norma Sanford. As the US entered the war, he joined the United States Army and was sent to Europe. He worked on architectural projects for the Army and was awarded the Bronze Star for his service. Back in the States, in 1946, with help from the G.I. Bill, he opened his architectural firm in New York.

Cavaglieri became best known as an urban preservationist and helped start and define the city’s architectural preservation movement. In a city where the norm was to demolish the old to make room for the new, Cavaglieri emphatically argued for the preservation of important buildings, believing that beauty from the past can and must inspire the future. He coined the term “adaptive reuse” to describe his design philosophy, which balanced an appreciation of historical styles with a bold modern eye. He first gained notoriety for the redesign of the metal and glass facade of the Fisk Building at 250 West 57th Street. Still, he is best known for the restoration of the Jefferson Market Courthouse into a Library in Greenwich Village. Among his other notable projects, he saved from demolition the Astor Library, originally designed by Alexander Saeltzer, converting it to house The Public Theater. He also designed (1962) and restored (1976) the Delacorte Theater in Central Park, which became the main venue for the Shakespeare in the Park Festival. A member of the Municipal Art Society, he was active in the protests against the demolition of Pennsylvania Station.

He was chairman of the National Institute of Architectural Education and president of the New York chapter of the American Institute of Architects. As the last of an impressive list of prizes, he received the Lucy G. Moses Preservation Leadership Award from the New York Landmarks Conservancy in 2002.

Mr. Cavaglieri worked steadily until the age of 93, two years before his death. His love and commitment to work and art can best be understood through an example: after seriously injuring his right arm, I learned to paint watercolors with his left hand, fulfilling, at last, his childhood ambition to be a painter.

Cavaglieri’s architectural drawings and professional papers are held by the Department of Drawings & Archives at the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia University in New York City.

Source: CPL Archives, Wikipedia, New York Times