The graphic artist’s Carbon illustrates an element’s journey from a star to his brain

We are delighted to repost a review of John Barnett’s beautifully conceived visual meditation on the cycles of life and the mysteries of matter. With a kindred sensibility to Levi’s own, this volume is not “inspired” by Levi’s Periodic Table, nor is an illustration of it. The result of meticulous and loving work, it flows like a conversation with Levi, that draws on disparate sources and invites us to think anew about humanity and nature. We thank San Lemonick and C&EN.

Sam Lemonick, reposted by permission of C&EN chemical & engineering news

Chemist and writer Primo Levi’s The Periodic Table—a memoir in the form of short stories about elements—closes with a chapter called “Carbon,” which tracks a single atom through time and space. Graphic designer and illustrator John Barnett has now adapted “Carbon” into a stand-alone book, the first he’s written and illustrated solo. Barnett retells the story in his own words, accompanied by pencil drawings that capture moments in the atom’s journey from its birth in a star to a nerve ending in his brain.

Barnett first encountered “Carbon” when he was in his 20s, traveling the world after dropping out of college. Barnett remembers that more than once, a person would hand him a book saying it would change his life. But Levi’s actually did—the story of carbon in particular. “It did for me a little bit what some might expect religion to do,” Barnett says. “It explained to me something about the universe and a beautiful way of connecting things together. It made the world seem like a different place.”

He was taken by the simplicity and the power of Levi’s central concept: everything past, present, and future is the same basic stuff taking different forms. Barnett says he has been thinking about adapting “Carbon” since he first read it. He wanted to find a way to make the story more visual—that’s his medium, after all—and to pass on Levi’s lessons to others.

It took 3 decades, but Barnett, now a freelance graphic designer, finally found time to do it. He can identify a few things that motivated him to tackle the project. He felt compelled to try to add something beautiful to the world amid the ugliness he saw in Donald J. Trump’s campaign and presidency. He also perceived an opportunity to provide a different presentation of the chemistry his two high school–aged children were learning.

The most pressing motivator was a degenerative eye disorder, retinitis pigmentosa, that has degraded Barnett’s vision over the last decade. He did the drawings in Carbon with his eyes just inches from the page. The progression of the disease “gave me some sense of urgency,” Barnett says, and made him want to spend a lot of time with each drawing. “I don’t know how much longer I’ll be able to see these things. I want them seared into my brain.”

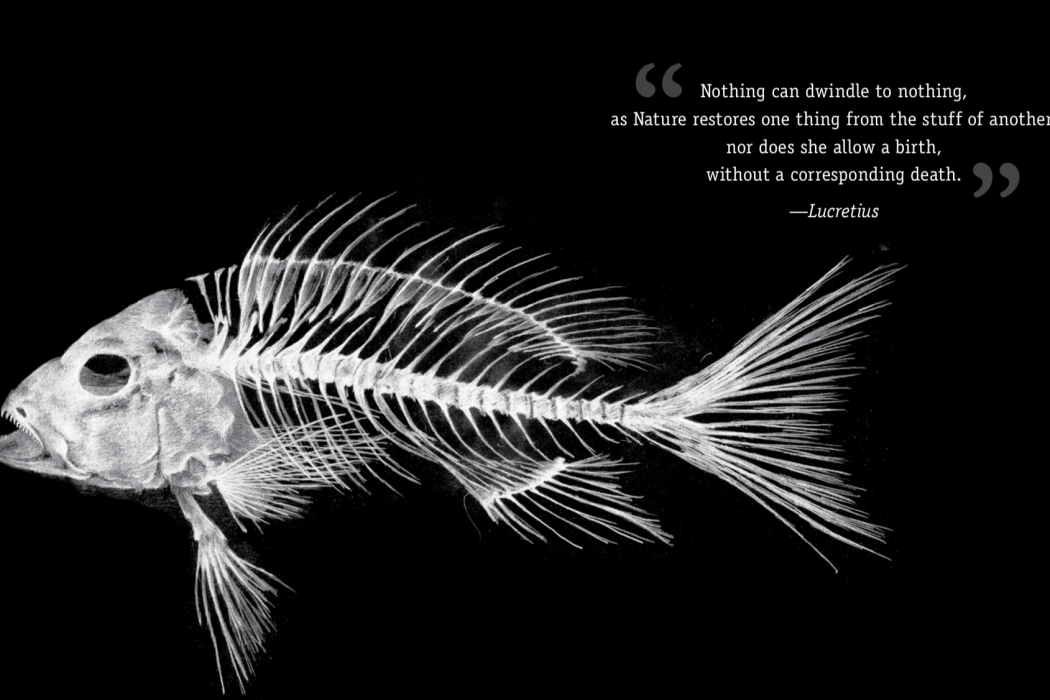

The drawings are stark and simple: black lines on white pages, or white lines on black. A few dozen words, at most, about what the carbon atom is up to accompany each illustration. Most pages also include a simple structure of a molecule. Some images feel like snapshots—a peregrine falcon flaring its wings, a horse midstride, a limestone cliff. Others are almost dreamlike: it takes a moment for rows of plants on a tea farm or a field of sea ice breaking up to come into focus. Barnett finds clever ways to bring Carbon’s theme of unity into the drawings too. A reader might flip back and forth between images of veins in a leaf and a sprawling city seen from above to wonder if they are actually the same drawing at different levels of magnification.

Carbon is not completely faithful to Levi’s original tale. Barnett compares his approach to the story to following someone else’s cross-country trip. There were a few stops, like carbon passing through the falcon’s lungs, that Barnett knew he would make. But he discovered other ideas he wanted to explore, especially in drawings. He decided to start earlier in time than Levi did, at the very beginning, the big bang. Barnett also introduced two interludes—just drawings, no text—at moments when the carbon atom was incorporated into carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

Barnett took those opportunities to make the atom a witness to humans’ growing imprint on Earth. The tea farm marks the spread of human agriculture. A polar bear approaching a rift in sea ice alludes to the effects of global climate change. One stark image shows a mass of plastic bottles and other trash bobbing in an unknown body of water.

Little of Levi’s version is left out, but Barnett shifts the focus somewhat. Levi’s prose lingers on the oxidation of a glucose molecule in the muscles of a galloping horse. In Carbon, Barnett elides the chemical reaction, and that feels OK. The eye gravitates to his drawing of the horse’s galloping legs, not the text.

Though Levi supplied the inspiration and raw material for Barnett’s book, other chemists helped shape it. With no formal science training, Barnett relied on scientists to make sure he got the details in Carbon right. Among those who helped was Roald Hoffmann, who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1981. Hoffmann is also a poet and playwright and, like Levi, a Holocaust survivor. At another chemist’s suggestion, Barnett emailed Hoffmann an early version of Carbondespite not knowing much about him. Hoffmann responded enthusiastically and worked with Barnett through different drafts to ensure that the details and chemical structures were accurate. Hoffman also wrote a foreword. “I think I couldn’t have found a more perfect person” to help with the book, Barnett says.

Because Carbon is his first book, Barnett is excited and nervous about its reception. Worried that people might not like it, he’s reminded of an exercise in an architecture class he took in college. The professor wanted the students to think about how other people would respond to their creations, so he asked the class to picture a building they had designed, then picture it covered in graffiti. Barnett already knows one thing he’d like to correct if Carbon gets a second printing, and it’s something chemists will appreciate: the periodic table included at the end of the book is not the version he intended, as it’s a few years out of date and has some typos.

Barnett doesn’t want Carbon to be his last book and is considering other elements to tell stories about. He’s particularly drawn to nitrogen and the story of Fritz Haber, whose work on ammonia synthesis led to large-scale production of both fertilizers and explosives. Haber also pioneered work on chemical weapons and developed an insecticide, Zyklon A, that was a predecessor of a product used to kill prisoners in Nazi concentration camps. “That could be an amazing trajectory for nitrogen, but it’s so goddamn depressing,” Barnett says. He wonders if it would be better to stick closer to Levi’s template and focus on an atom rather than a person.

Right now, Barnett is waiting for people’s reaction to Carbon. Perhaps it’s no surprise that he comes back to the imagery of a journey: “We’ll see,” he says. “It’s at that point when the rubber hits the road.”

John Barnett was born in Buffalo, New York, in 1963. To date, his favorite job was as a shepherd in Cornwall, England. For many years he enjoyed working as a carpenter, even building his own sailboat, which, the last he knew, still floats. For the past decade he has called himself a graphic designer and illustrator, skills he has applied toward many books. This is the first of his own. The drawings within were done “old-school” with fine-tipped mechanical pencils on paper. He lives along the shore of (and quite often on) Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island with his wife and three children.