The Renaissance and the Ottoman, edited by Anna Contadini and Claire Norton, Routledge, 2013

The Renaissance is commonly understood as a distinctly Western, European, Christian phenomenon. We might think of the sculptors and painters of the Italian peninsula, commissioned by patrons in the region; we might imagine the rulers and intelligentsia of Southern Europe, who framed themselves as the successors of the classical Greek and Roman civilizations; or we might recall the Protestant Renaissance in the Netherlands. This view fits comfortably into a framework that posits a distinct Western and Christian history, and simultaneously works to solidify the idea of that history. In this circular way, the Renaissance can be understood as both a feature of, and evidence for, a continuous and defined Western Christian civilization.

Yet rarely does the reality of history fit into such neatly defined conceptual categories, and while these simplified narratives can be helpful for a general understanding, new Renaissance and Ottoman scholarship invites us to reassess these stories we tell ourselves about this period. The authors of The Renaissance and the Ottoman World seek to set the groundwork for a different framework – one that aims to blur these conceptual boundaries that are at odds with the history as presented by the evidence, and to “situate and acknowledge the role that the Ottoman Empire played in the Renaissance.”

Yet rarely does the reality of history fit into such neatly defined conceptual categories, and while these simplified narratives can be helpful for a general understanding, new Renaissance and Ottoman scholarship invites us to reassess these stories we tell ourselves about this period. The authors of The Renaissance and the Ottoman World seek to set the groundwork for a different framework – one that aims to blur these conceptual boundaries that are at odds with the history as presented by the evidence, and to “situate and acknowledge the role that the Ottoman Empire played in the Renaissance.”

The Renaissance and the Ottoman World, originally published in 2013, is a volume of thirteen articles written by historians across an array of disciplines. Each article is in service of the broader project of the book, which as the title suggests, seeks to integrate the Ottoman Empire in our understanding and framing of the Renaissance. The book is broken up into four sections, titled: Commercial, Artistic and Cultural Contexts; Texts, Art and Music as Media for the Transmission of Intercultural Influences; Renaissance Thought; and, The Renaissance and the Ottoman Empire. Within each section are three to four articles that focus on an event, object, or area of history that feeds into the book’s larger themes. One discusses shared artistic motifs featured in material culture, another on the intercultural transmission of books, another on the patronage of Greek philosophy, etc. In this way, rather than provide a broad case for a new view of this history in general terms, The Renaissance and the Ottoman World instead opts to demonstrate it directly, through individual case studies that each exist as supporting evidence for that view. As Claire Norton writes in the book’s initial chapter, titled Blurring the Boundaries: Intellectual and Cultural Interactions between the Eastern and Western; Christian and Muslim Worlds:

“…the Ottoman Empire…proves an illustrative example that foregrounds the constructed, rhetorical nature of the conceptual dichotomy between Christian and Islamic, Western and Eastern worlds. The Ottomans did not occupy a different intellectual, commercial, or political world to the Christian Europeans. The Mediterranean was a world traversed by commercial, cultural and intellectual networks through which ideas, people and goods regularly travelled. What sense does it make to discuss the Renaissance solely as an Italian, or Western-European phenomenon when we know that the Ottoman and Italian architects were influenced by each other’s designs and techniques; artists crossed borders and worked for different patrons; rulers in the East and West…engaged in the same practices and ceremonies…read the same books, commissioned the same maps, and exchanged military, scientific, and philosophical knowledge?”

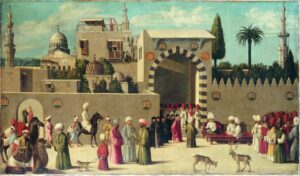

Reception of a Venetian Delegation in Damascus in 1511. Attribited to the workshop of Gentile Bellini.

What follows is a series of articles that demonstrate the need for a new historical framework that does not operate on a rigid and unhelpful paradigm, which fails to account for much of the historical evidence on display in this book. Two fascinating chapters discuss books as material objects of history, and their embodiment of intercultural exchange. Chapter 11: Binding Relationships: Mamluk, Ottoman, and Renaissance Book Binding, provides an in-depth look into the heavy influence that Ottoman book-binding techniques had on the practice of book-making in Venice, a major printing hub of the West during the Early Modern period. Similarly, Chapter 4, titled The Role of the Book in the Transfer of Culture between Venice and the Eastern Mediterranean by Deborah Howard, is another example of this connected history. Travel and merchant writers embarking primarily from Venice towards the East have provided us with a wealth of literary sources, several featured here, which give us insight into the attitudes of these travelers venturing into the muslim world. Several writers present write of their experiences in the courts of Damascus, or journeys to Aleppo and Alexandra, “…with their resident colonies, which were regarded as so familiar that few Venetian visitors felt the need to describe them.”

A project such as this, however, naturally runs the risk of replacing one over-generalized narrative with one that equally lacks in nuance. This is what Norton describes as “exchanging one homogenising historical frame for another”. The nuance that is absent in seeing the Early Modern world as one of clashing Eastern and Western civilizations whose interactions are defined in terms of religious difference, would be equally absent in a view that posits a rose-tinted version of history that ignores the cultural differences that were present and relevant to imperial interaction. Thankfully, this is a trap that the book does not fall into, and the complexities of the relationships it describes are fully acknowledged. The article Turning a Deaf Ear by Owen Wright for example, does not shy away from discussing how there was in fact a significant and mutual lack of interest in the musical culture of the other between the Ottomans and Christian Europeans. He writes of this lack of interest as:

“…a pallid reflection of the standard propagandistic view of that time of the Turks as savage invaders notorious for their cruelty and bloodlust. The complete absence of sympathetic response in this particular instance, let alone of musical exchange or transfer, may be regarded as symptomatic of a wider Western indifference at the level of high culture to the Ottoman musical other, and one reciprocated by Ottoman attitudes to European music, that appears to typify the fourteenth to mid-seventeenth centuries.”

As always the story is more complex, and he covers the substantial influence that Islamic instruments, ornamentation, and Ottoman military music had on the musical scene of Western Europe. In this way, the book manages to avoid the tendency to overcompensate in its effort to challenge the predominant narrative it seeks to change. The point is not to disregard difference, but to establish a historical framework that does not completely center religious difference which overshadows the connections and similarities that were just as, if not more historically significant. In an earlier chapter we see how Ottomans and Western Europeans used the same symbols as forms of power-legitimization, notably portraying themselves as successors to Alexander the Great. Sonja Brentjes’ article on maps of Anatolia show how Western Europeans came to view themselves as sharing the same cultural space as the Ottomans. Articles on book transfer or textiles further demonstrate commercial and cultural ties between these two seemingly disparate civilizations.

All of this depth and multi-dimensionality is lost when we see this period exclusively through the East-West paradigm – that filter which prevents nuance and through which can flow prejudice, nationalism, and an ideology-ridden view of the past. And while this idea manifests in the present and continues to be propagated, it is hardly a modern phenomenon. As is demonstrated in several of the book’s chapters, these narratives stretch back to the Early Modern and Medieval eras themselves, in which leaders worked to manufacture and spread ideas of cultural, and moral, division to serve political ends. Therefore the purpose of this book is not simply to recontextualize this history to address contemporary narratives, though naturally that is part of the project. In a way the book also seeks to address narratives that existed during the Early Modern period itself, as top-down political tools used to conceptually isolate and elevate the Christian world, and inspire animosity towards the muslim power in the Mediterranean.

The parallels between the past and present appear across the book, but are most prominently a feature of Chapter 8: Old and New Demarcation Lines between Christian Europe and the Islamic Ottoman Empire, by Zweder von Martels. This chapter discusses Pope Pius II and his (likely unsent) letter to Mehmed II urging him to convert to Christianity in exchange for an imperial crown and recognition of his authority over the former Byzantine Empire. It draws a comparison between this event to modern day geopolitical relations, specifically Turkey’s potential admittance into the European Union. In both cases, a condition is attached to the offer of integration, which in the one case is the acceptance of Christianity and in another is the adherence to the EU’s convention on human rights. A notable problem with the article lies in the two fundamental assumptions on which the argument rests: the first being that “Turkey’s admission to the European Union looks nearer than ever”, and the other, that “…human rights have become the leading principle of guidance for the relationship between nations.” These assumptions seem misguided at best, on both counts. It isn’t entirely detrimental to the argument that the author did not possess the clairvoyance to predict the trajectory of the relationship between Turkey and the EU in the decade following the publishing of the book; slightly more difficult to overlook is a human-rights-based view of the geopolitical landscape as that seems at odds with reality both past and present.

The development of attitudes towards the muslim ‘other’ is more effectively explored in Chapter 3: The Lepanto Paradigm Revisited, written by historian Palmira Brummett. Lepanto was the venetian name of a port in the Gulf of Corinth, and was the site of a famous naval battle that took place in 1571 between the Ottoman Empire and the ‘Holy League’ – an alliance between various Catholic powers of southern Europe. The Battle of Lepanto has come to represent a pivotal confrontation between the Christian and Muslim world, and as put by Brummett, “…was mapped not simply as a ‘famous sea battle’, but as a triumph for Christendom against an apparently unstoppable foe.” In her chapter, Brummett examines the historiography surrounding this event, and how it “…serves a place, a space, a time and a marker for the historiography of what is still too often called ‘Islam and the West’, or the Ottomans and Europe.” Claims that this battle marked the end of the supremacy of the Ottoman Empire in the Mediterranean are regarded by many scholars as exaggerated, since the Empire remained a prominent player in the region for centuries after. And with that position came a continued relationship that continued to feature intellectual, cultural, and material exchange. Yet even at the time, the battle was characterized by a pressing need to fend off the Turkic invaders, with all their savagery and heresy, and to bolster the idea of a civilizationally unified Christian West.

The idea isn’t that military confrontation was not a key feature of the relationship between the Ottoman Empire and the maritime Christian empires of the Mediterranean. There is a rich military history that has seen extensive scholarship exploring the imperial struggles between the Christian and Muslim powers of the region. However, the presence of this history is not necessarily evidence of a relationship exclusively characterized by animosity and conflict. In fact, it can be quite the opposite, especially if we think of conflict as one of the various natural modes of encounter – alongside communication, trade, and migration – between empires operating in a shared space. That the Ottomans competed for territory in the Mediterranean with neighbouring empires such as Venice in fact supports the idea that they were, and should be viewed historically, as part of the same cultural and geopolitical environment. Brummet’s detailed account of the historiography of the Battle of Lepanto makes apparent flaws in scholarship that makes use of conflicts such as this to reduce multi-faceted relationships to simplified and often ideological narratives.

This exploration of historiography is in fact a feature of the book prevalent throughout, and gives the reader fascinating insights into the process of constructing and reconstructing history. The show-don’t-tell approach that The Renaissance and the Ottoman World adopts makes the arguments all the more compelling. Each self-contained article conducts a detailed analysis of the subject matter, showing us the links and relationships it argues for rather than insisting their presence and explicating an ideological position. Just as with Brummet’s article, Brentjes aforementioned article on maps details her process and the evidence of her claims. We are exposed to tables that feature etymological linguistic analysis; she gives a thorough account of her sources, their effectiveness and limitations; and she provides a review of adjacent existing scholarship.

Each article opens up a new field of history, littered with references and sources for potential further exploration. The history of art, pottery, literature, book-binding, intellectual scholarship, cartography, war, diplomacy, historiography and more, are all on display in clear and concise essays written not to overwhelm but to immerse the audience in this connected history. As much as there is for the average reader to learn of the Renaissance and the Ottoman Empire, this work is an insightful window into a new academic movement, and the process of historical scholarship.

Image: Anonymous author, Pietro Mocenigo, Capitano Generale da Mar, 17th century. Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia—Museo di Palazzo Mocenigo.