The resurgence of the Italian silk tallit.

Alessandro Cassin in conversation with Rav Umberto Piperno

Many of us remember well the years Rav Umberto Piperno spent in New York: his enthusiasm, wisdom and tireless efforts to present the specific traditions of Italian Jews from liturgy to food and beyond. In July he is back in Manhattan to present yet another intriguing project: the revival of the dying Italian tradition of the silk tallit, the prayer shawl. An enterprise rooted in the wisdom of the past, the passion of the present and the innovation of the future.

Alessandro Cassin: The tradition of the Italian tallitot involves not only a long tradition of craftsmanship, but also a cultural history, and mercantile exchange.

Rav Piperno: Absolutely. Today it gives an added dimension to the many stories that concern the Silk Road, the fascinating network of trade routes. It was central to cultural interaction between different parts of the world comprising both a terrestrial and the maritime routes, connecting Asia with the Middle East and southern Europe.

The effort to highlight and revive the Italian Jewish tradition of the silk tallit is spearheaded by two entrepreneurs, Dora and Sofia Piperno, with rabbinical guidance and assistance.

AC: How and where did the project begin?

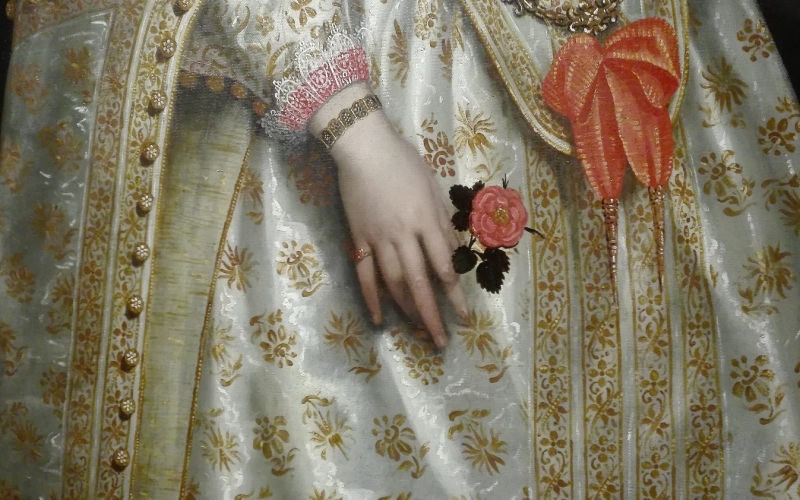

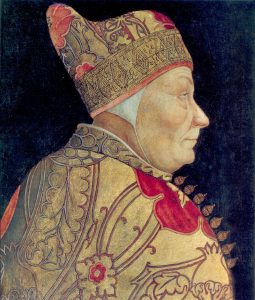

RP: It began in the Veneto region in two phases. In phase one, the Chief Rabbi of Rome, Riccardo Di Segni went to Venice, historically one of the main cities in the west connected to China through the Silk Road. The idea was, to begin with, an in-depth analysis of the precious robes of the Venetian Doge which were made in silk and gold. One of the aims being creating silk tallitot decorated with actual gold thread. The challenge was to find a silk production facility, where 100% Italian silk could be spun under rabbinical supervision, starting from the silkworm’s cocoon to arrive at the silk thread that will form the tzitziot. One such artisanal manufacturing plant was found in Nove, near Venice.

With an eye to marketing the new silk tallitot, they came up with the catchphrase “filo-so-fare” a wordplay which means both “I know how to spin thread” and “to philosophize.”

AC: What do kind of rabbinical supervision is needed?

RP: The concern is for the tzitziot, the fringes at the four corners. According to the Torà, we must wear a shawl (talled) with fringes applied at the four corners. These fringes must be handcrafted by an observant Jew.

AC: What do kind of rabbinical supervision is needed?

RP: The concern is for the tzitziot, the fringes at the four corners. According to the Torà, we must wear a shawl (talled) with fringes applied at the four corners. These fringes must be handcrafted by an observant Jew.

So Rav Di Segni with Mr. Pino Arbib began the first phase which requires two days of work: the roughing (sbozzatura), and the first washing of the thread. I was in charge of the second phase which took place in Oderzo, near Treviso and consisted in the matching of the silk threads (abbinatura), crossing them over, and subjecting it to a second washing, which requires three more days of work leading to the finished tzitzit.

Just like in the production of kosher wine all these procedures (even when they consist of a mechanical action) need to be initiated by an observant Jew. Every time that we push a button or make an action we must say: leshem mitzvah tzitzit, specifically to create a tzitzit. It must be lishma, that is, the intention has to be specific to that purpose.

AC: How long have Italian Jews been producing silk for this purpose.

RP: It’s a long and exciting tradition, which took root in many different Italian regions. I found a responsa by a rabbi in Gorizia in the north east of Italy, in 1630 who was asked: “can we feed the silkworms during Shabbat?” But there were Jews producing silk in the south as well. My research leads me to believe that there was silk production in Calabria before it arrived in Venice.

AC: Silk was essential to the economy of southern Italy, among both Gentiles and Jews. The first city to introduce silk production to Italy was Catanzaro, in Calabria, during the 11th century. The silk of Catanzaro supplied much of Europe and was sold at a vital market fair in the port of Reggio Calabria to Spanish, Venetian, Genovese and Dutch merchants. The city was world-famous for its excellent fabrication of silks, velvets, damasks, and brocades. Other cities involved in silk production over the flowing centuries were Lucca, Florence, Genoa, and Venice, which all had Jewish communities…

RP: In Soriano Calabro, which was perhaps one of the centers of Jewish life in Calabria and a textile hub as well, I was told that up to thirty years ago most housewives had looms in their homes and spun silk…

AC: Soriano as a Jewish last name is found in Rhodes and much of the Mediterranean…

RP: Soriano plainly indicates a Sephardic origin, it means those who came from Soria, in Spain, so perhaps Soriano Calabro was a destination for Jews fleeing Spain.

AC: Is silk production still alive in Calabria?

RP: A young woman, Miriam Pugliese, has recently begun silk production as well as a small museum about this tradition, in San Floro, near Catanzaro. She is raising silkworms, and producing her silk spun and woven by hand! I have been raising some funds at my synagogue in Rome so that in October I will go to her and she will teach some students to spun and weave silk.

AC: Tell me more about the Italian tallitot tradition, how long ago did they stop making silk ones and why?

RP: The silk tallit —we call it talled—stopped being available about 60 years ago when silk production became rare. At that time lightweight synthetic tallitot became available at very reasonable prices as well as wool ones from Israel and from the Ashkenazi tradition. I believe that in a trend to imitate what they saw in Israel, many Italian adopted the woolen one. All of this is fine, perhaps normal, but I insist that there is something important that gets lost each time we abandon something that has been a part of our own specific tradition

AC: Today does one still see many silk tallitot in Italian synagogues?

RP: No, only a small number. In part because the silk ones are used only on special occasions like weddings, and no longer used every day.

AC: What other materials are used for tallitot around the world?

RP: Other than silk the most commonly used fibers are wool, linen, as I mentioned synthetic fiber or even cotton. I would be curious to know what the tallitot were like in Afghanistan and India. In Calabria, I discovered that in Ferramonti (a Fascist internment Camp) some Jewish internees who lacked almost everything managed to weave burlap and make tallitot for themselves.

AC: You pointed me to a website, www.talleddiseta.it where one can find the new Italian silk tallitot we have been discussing. I notice that they offer them in the traditional light blue stripes as well as in green, red, and dark red. Where those colors part of the tradition?

RP: Those are new colors, emphasizing the desire for novelty and innovation. In Italy, as in much of the Sephardic world we traditionally used white silk with light blue stripes. In the Ashkenazy world, the tallitot were made of wool. They were white with black stripes. But the Sephardim in North Africa, for instance in Morocco, also used wool ones… And in Djerba, off the coast of Tunisia, they made them in a characteristic local coarse black wool.

AC: Do you have an opinion on the very colorful ones?

RP: The sages tell us that one talled should not stand out from the other ones in the congregation. A too garish color can distract from concentration during prayer. I think that in the privacy of one’s home, one can wear any color, but in a public situation, it is best not to stand out too much.

AC: Do you think that the light blue stripes derive from the traditional blue thread in the tzitzit?

RP. It is probable. But that is a different and long tradition and halachic discussion. The Torà tells us in the Shema that you will make tzitziot at the four corners of your garments for all generations. One of four threads of the tzizit must be blue.

Maimonides talks about this blue thread as do the geonim, that is commentators who wrote after the Talmud up to the 12th Century. After that, there is no more discussion of the blue thread.

AC: In Italy, when did they stop having the prescribed blue thread in the tzitzit?

RP: I have not researched this but frankly I am not sure they ever had it. That custom was dropped early on, as the mollusk that produces the ink became hard to find. When you think about it is paradoxical that the die needed for a prayers shawl should come from a non-kosher sea creature.

AC: In the Jewish ritual, there is much covering and uncovering with cloth, I am referring to the mappot for the Sefer Torah, for example. In which sense the talled is a form of covering?

RP: The talled is a garment this it is also a form of covering. But there is a more far-reaching function, which is that of creating a family. In our tradition, the talled is given by the wife to the husband on the day of the wedding as a symbol of fidelity and unity. If you look at my hand, you will notice I do not wear a wedding band.

The man gives a ring to the woman, and the woman gives the man she is marrying a talled. It represents and sanctions of the union between husband and wife. In other traditions, things are a bit different.

AC: How so?

RP: In the Ashkenazi tradition, at the end of the wedding, husband and wife retreat in a secluded space for 8 minutes, with witnesses. And this seals their union. According to Sephardic thought, this is not necessary, because the union is already sealed the moment, at the end of the ceremony, when they jointly receive the blessing both under the talled. It is under the talled that the union comes into being.

AC: Today one sees Hassidim and other ultra-orthodox men donning the tziziot of the tallit katan the undergarment, visibly outside their clothes… Does it point to a more ostentatious affirmation of religious identity, compared to a more intimate and private Sephardic tradition?

RP: In Italy, we never wore the tziziot hanging outside our clothes. In truth, it is not prescribed by the halakha. The halakha simply tells us: ureitem oto (וּרְאִיתֶ֣ם אֹת֗וֹ) (You will see it) to remind us when to wear it, that is from dawn to sundown, but not at night. “You will see it” does not refer to showing it to others but rather that it must be worn during the light hours of the day rather than at night.

In truth, the tzizit does not have any identifying or ostentatious function, but instead, I would say, a mnemonic one, like tying a knot in a handkerchief. The tzitzit is looked at during the tefilah, the prayer, and particularly the Shema. It has many knots to remind us the name of our blessed God.

AC: In the Italian and Sephardic traditions, boys begin to wear the talled starting from the bar mitzwa, but in other traditions much later…

RP: The Ashkenazis, start wearing them from the day of the wedding (before that the only wear a smaller undergarment, talled katan). Because of this, in synagogue, it is easy to spot bachelors as they are the ones without the talled... This custom rooted in the beautiful idea that a man is complete once he has found a wife, the talled being the symbol of this union and completeness.

AC: For Italian Jews, the silk talled is also a cherished heirloom…

RV: Exactly. Rather than worn every day, it is usually cherished and worn on special occasions particularly on the wedding day, and it is often passed down from father to son for generations.

In Rome, during the summer, between Pesach and Sukkot— on Friday night or weekdays when wearing a talled is not mandatory, the chazanim (cantors) wear a silk talled. To emphasize that it is not compulsory on those days, they wear it as a shawl around their neck, without covering the shoulders.

AC: What do you feel is the significance and prospect for the re-introduction of the silk talled in Italy?

RV: I think it can and will help better define the specificity of our tradition.. Through the talled—which is usually a gift for a bar mizwa or a wedding— we can begin a journey that brings us back to our fathers, grandfathers, and ancestors. It can also be an occasion for self-discovery, and a step in a journey that can take us into the future with new pride in our traditions. There is no need to conform to what other Jewish communities wear, we have our own. We must teach our youngsters and bridegrooms to embrace their history, from food to liturgical and cantorial traditions. The talled, is part of this patrimony of Italian Judaism.

Others will ask: “ma nishtana” (in what are you different from others?), and this can hopefully ignite conversations, mutual knowledge, and exchanges.