What follows is Alessandro Di Rocco’s acceptance speech of the Centaur Award 2018.

I want to thank all of you for being here tonight. I am honored and humbled by this tribute.

If, as Primo Levi says, “every man is a centaur,” my two halves have been a wondrous sense of life eventually channeled into Judaism, and the world of disability, which I have inhabited since birth, and which continues to be a part of me in my chosen profession of neurologist.

There is perhaps more than one centaur in us. We belong to the randomness of life, to a mix of biology and circumstances, a mix that some would define as destiny, and takes us to different paths of existence, delightful or senseless, peaceful or painful, meaningful or harrowing.

Primo Levi’s Auschwitz can be read as the incredulous observation of a man of science and reason, an investigator reporting on the result of an absurd experiment. He studies humanity captured in an extreme and unprecedented setting, as if looking at a laboratory experiment, and he is both a participant and an outside observer.

He warns us to learn the lesson of this monstrous experiment, yes, of course so that it may not happen again, but, also because “what exists in extreme situations also exists in less abnormal settings.” As a scientist, he looks at the horror of the human laboratory of Auschwitz not just to testify, but to draw observations that go beyond the experiment, an explanation for human behavior and the overall ethical and psychological making of mankind. He was a chemist, but his study was on the neuropsychology of dehumanization.

I always wondered whether Primo Levi ever became familiar with an experiment in neurobiology, an animal model for depression, commonly used in research laboratories. It is called “learned helplessness” and consists of administering painful electrical shock to caged mice or rats, randomly, no matter what they do, whether they drink or eat, on their running wheel or while asleep. As there is no pattern, there is no possibility to develop an escape strategy. Eventually, the animals resign to the pain, cease to look for food or water. They are defeated. These animals are then used for testing the effects of antidepressants or other psychiatric drugs.

This experimental model has also been adopted by military psychologists around the world, including the US, by accomplices of torturers, to inform and implement the most dehumanizing torture methods.

Indeed Auschwitz was also a terrifying neurobiological experiment.

Primo Levi’s The Drowned and the Saved is ultimately an essay on human behavior, a reflection on the moral collapse of perpetrators, victims, and the many “grey individuals” who inhabit the nebulous space between oppressors and victims. They are “those who pretended not to see or were just turning their head away”. It is indispensable to know them “if we want to know and understand the human race, if we want to be able to defend our souls should such challenge appear again, but also just if we want to understand what happens in everyday life, in a factory or in an office”.

Levi gives us a strong and repeated admonition: “take this lesson not just as a testimony, but as an observation on human nature, on what can be in your own home, in your office”.

I imagine that I am not the only one who has felt embarrassment when reading about the human degradation of the lager and applying the moral degradation of a kapo to the much less brutal moral degradation of a physician who fails a helpless patient or an administrator who “cures” and cheats on a budget.

Note, that Primo Levi warns us on how we shall defend our souls, as the ultimate insult of the camps was not the pain and deprivation, not even death, but the moral degradation and collapse, the death and annihilation of the soul. This annihilation of the soul occurs when dehumanization erases all forms of dignity.

The neurological world that I inhabit is a world of intrinsic dehumanization and indignity, but also one of great humanity and affirmation of life.

Neurological diseases slowly decompose the essence of a person: “is this a man” who does not remember his wife’s name, whose trembling hands have lost all use, who urinates and defecates on himself, whose mind is occupied by nightmares and frightening hallucinations, whose legs do not generate steps. Yes, this is a man, a woman, a father, a mother, a sister.

He can feel and experience and be a participant of the collective breath and beauty of life. If only he had the right medicine and the right therapy, and the right attention, if only he were not pushed into neglect by an indifferent health care system.

At the end of the line lies de-humanization: the awareness of disappearing as human beings, even in the eyes of your own doctor. It is the indignity of being treated as a lesser human that annihilates the soul.

Just in the past few days, while I was writing these notes, I had conversations with a patient and a spouse of a patient, both confiding their loss and sense of dehumanization, both sharing stories of personal and familiar rejection, both rejected by an indifferent or dull health care world, both already feeling non human and invoking death.

For those of you who are in the health care system, or the education system, or the immigration system, dehumanization and humanization are part of our daily duties.

And the abyss of dehumanization is only arm’s length away. In history and geography, our own horror surrounds us. In Staten Island the Willobrook School for Children and Adults with Intellectual Disability, for people just like my intellectually disabled sister, was a gigantic open lager, with people chained to their beds or to the heaters, beaten and abused, with “researchers” who were conducting studies on hepatitis inoculating unaware children hosted by the “school”. Ethically this was not distant from Auschwitz. Its horrors were made public in the 1970s but the school was forced to close only in 1987.

The gigantic Harlem Valley Psychiatric Institute and many other psychiatric detention centers can only be seen as dehumanizing and terrifying black holes of human consciousness, medical profession, and misuse of scientific knowledge. Until the late 1980s, agitated patients were often forcibly tied and closed in a dark pit, a cage. Doctors, nurses, and polite administrators who approved budgets for the cages did this.

And who knows what happens in refugees’ camps in Syria and around the world, among smugglers of human beings. Who knows if they participated of that shame that Primo Levi describes, of that sense of being part “in a common inner desolation.”

As I remind my students and residents, medicine is easy, soon artificial intelligence and an algorithm will surpass all our diagnostic skills and will create algorithms for the perfect treatment.

Our role is to affirm the dignity and humanity, or better, to alleviate, as much as we can, the de-humanization of the disease.

I will come to my conclusion with a quote from Primo Levi:

“The Germans did not win, because we kept our humanity, including the shame for having being dehumanized..’

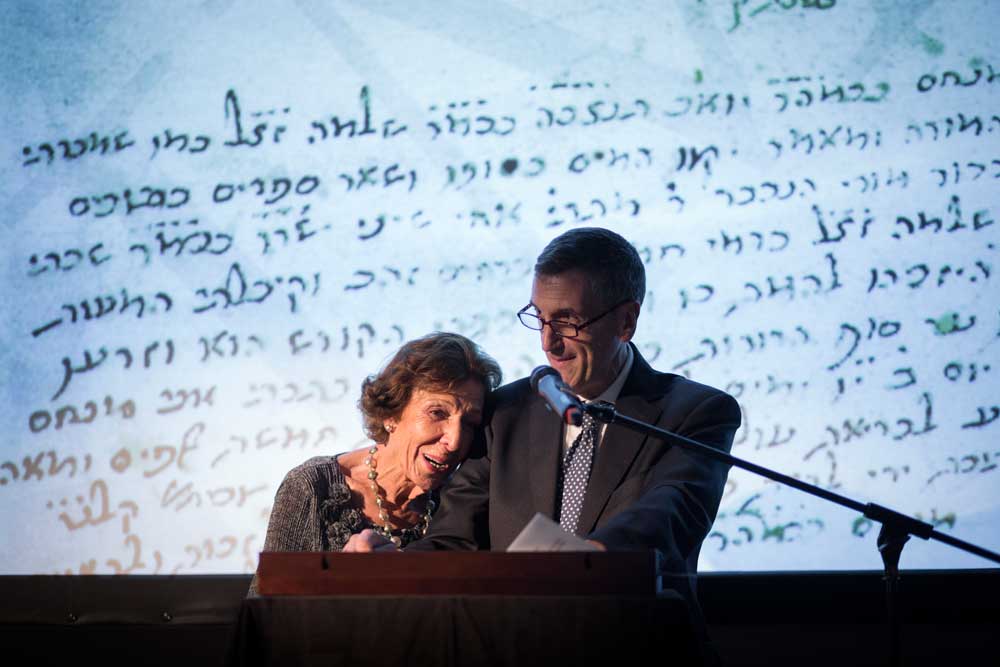

I will tell a story, about my muse, my acquired “other mother,” my beloved Stella Levi, a board member of the CPL who is here tonight and agreed to let me share it with you.

Three years ago, Stella and I were at a diner in the city and were talking about conflicts and what they do to people, how they change humanity and separate the way we see ourselves and the way we see the other, and the difficulty to end them.

Stella began to tell me a story: “When we were liberated, we stayed for some time in a camp near Munich. The Americans had brought food and medical help. After Auschwitz, for the first time we could eat and liberate our feelings of mourning for our mothers and fathers who had been killed. One day, my sister and I went to Munich and saw Germans who had lost their homes in the bombings. Long lines of people, hungry, without anything, waiting for a little food. Their sight brought tears to our eyes.

This is why the Nazis did not win. Their ultimate goal was that of dehumanizing, millions of people in the camps deprived of their name and their history, of their humanity. But they failed, and Stella and her sister moved by lines of destitute Germans, only a few days after their liberation from the camps, is the reason the brutality and stupidity of these dark times will not prevail. I am comforted by the thought that surely there are other Stellas in refugee camps in Syria or in any corner of the world where human dignity is under attack. This is also why we think there is a need for a Centro Primo Levi.

I thank you for this honor and for being here with us tonight.

As a physician and a scientist, Dr. Alessandro Di Rocco has touched and changed the life of many people. He arrived in New York in 1996 on a Neurology and Movement Disorders fellowship under the supervision of Dr. Melvin D. Yahr, towering figure and innovator in Parkinson’s disease. After a tenure at Mount Sinai Hospital and Beth Israel, in 2006 Dr. Di Rocco embarked in a new adventure. Based on is vision and expertise, he started and built what is now the Marlene and Paolo Fresco Institute for Parkinson’s and Movement Disorders at NYU Langone Medical Center and a wellness program for for Parkinson’s disease at JCC. He is now working on the expansion of this model at Northwell Health System in his new position as System Director Parkinson and Movement Disorders. For his achievements and vision, Dr. Di Rocco seats on the Board of the Parkinson Foundation, an organization born to provide life-changing support to people with Parkinson’s disease and their caregivers. Dr. Di Rocco’s scientific interests are primarily related to the understanding the bases of Parkinson’s disease and to find novel treatments for the symptoms that are plaguing the patients. Each patient as a unique and invaluable person as part of his/her own family, environment and community. Care needs to be approached with reverence, time and humility, irrespectively of census, gender or culture. Based on his vision and expertise, he has implemented for the patients and caregivers a model of integrated care that embraces not only the due medical components, but also education, rehabilitation, exercise and creativity.