Raffaele Bedarida is an art historian and curator specializing in Italian art, politics, and cultural diplomacy in the mid-20th century. Assistant professor of art history at Cooper Union, he regularly lectures on modern and contemporary art topics at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and MoMA. He holds a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center. Bedarida is the author of two books in Italian, Bepi Romagnoni: Il Nuovo Racconto (Silvana Editoriale, 2005) and Corrado Cagli: La pittura, l’esilio, L’America (Donzelli, 2018). He is currently working on his book manuscript: Art Exchange Across National Boundaries: The Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935-1969.

In the 1930’s the young Italian artist, Corrado Cagli was a rising star of the Scuola Romana, supported by the Fascist regime despite being both Jewish and a homosexual. Following the Racial Laws, he fled first to Paris, and then to the USA, where he remained until 1947. Raffaele Bedarida’s new book, Corrado Cagli – La pittura, l’esilio, l’America (1938-1947) Donzelli Editore, 2018 (soon to be translated into English by CPL Editions), focuses on Cagli’s American exile.

While examining Cagli in the context of the artistic and intellectual migration from Europe to the US, Bedarida provides valuable new insight into the specific plight of this Italian Jewish artist, once championed by Fascism and into the complexities of the use of art for cultural diplomacy.

The author combines biography, cultural history, and critical analysis in exploring a decisive period in the life and work of a painter whose complex personality and non-signature style, defy classifications. The book also provides thought-provoking and nuanced arguments on the ideologically based ostracism that Cagli encountered upon returning to Italy in the immediate aftermath of the war. Because of his past as a former regime-endorsed artist, his recent American success, his participation in the liberation of Europe from Nazi-Fascism with the American army, and Jewish exile, Cagli simply did not fit into any of the faction of Italy’s post-war heated cultural disputes.

Based on extensive original research and written with brio, Bedarida’s book is an essential contribution to a growing field of studies that examine how, by welcoming artist and intellectuals in flight from Nazi-Fascism, the United States had been given what Will Norman has called “custodianship for a civilization.”

We met Raffaele Bedarida at Cooper Union where he is Assistant Professor of Art History.

Alessandro Cassin, you first started to work on Corrado Cagli as a student…

Raffaele Bedarida: Yes, it started with a thesis when I was at the University of Siena and Enrico Crispolti, one of the major scholars who has written about Cagli, was my adviser. Crispolti is among the most influential Italian critics and art historians of the second half of the twentieth century, and Cagli was one of the artists who had a great impact on him. Usually, it’s the other way around, one considers how reading some theoretical text is crucial for an artist’s work, but here instead you have the work of an artist becoming important if not central to the methodology of a scholar.

AC: Your book begins with — instead of a preface— with an insightful and flattering letter to you by Crispolti, which sets a specific, very personal tone.

RB: Crispolti is one of the most generous persons I’ve ever met. And I love how, in his letter, he also disagrees with me on a key point of the book!

AC: Your work on Cagli’s American years, in effect, brought you to America…

RB: I had an opportunity to come to New York and begin my research thanks to an exchange program between the University of Siena and CUNY. I first came here through that program in 2003 and started the research that resulted in my thesis, which I defended in 2005. So the book has an autobiographical dimension, in the sense that it was by studying Cagli’s exile that I first made contacts with the academic world here. For my Ph.D., at CUNY, I soon focused more broadly on the artistic exchange between Italy and the U.S. during and after the war.

AC: Before the thesis, had Cagli been important to you, had you felt drawn to him as an artist or as a personality?

RB: He was not among the artists I was instinctively most drawn to, and yet he had sparked my curiosity. Essentially I did not get him; I did not get his work! Still today, I find it very difficult to “frame” him. I had the perception that I was missing something, that there was something significant that eluded me and had remained untold.

AC: Was it more of an intellectual curiosity, than a visceral attraction to his work?

RB: Definitely. I wanted to solve something, which did not seem to add up. Even his Jewish identity: although I can find in Cagli’s life many of the places and events of my family history, I could not find much familiarity in his way of dealing with his Jewishness as he faced persecution and exile.

AC: Your book is certainly a vital contribution to understanding this complex and often contradictory artist, but do you feel you solved the puzzle he initially represented for you.

RB: What I can say is that working on this book made me aware of the methodological problems of any study of cultural exchange, migration, and exile. It helped me formulate some questions and tools to situate the work of an artist such as Cagli whose contexts of reference change dramatically in a short period of time. These issues, in turn, became the subject of my Ph.D. project.

AC: Which was?

RB: A more general study on how Italian artists presented and promoted their work in the United States from the 1930s to the 60s. Cagli spearhead my work on the concept of cultural translation. Studying his work made me focus on the relativity the language and intellectual framework through which his work had been significant first in Italy, and later in the context of American art. And further, how Cagli’s artistic trajectory can be reframed in the context of the experience of Jewish exile during fascism. There are many layers, and each one speaks a different language. As an art historian, all of this made me radically rethink the art of that period.

AC: This book focuses on Cagli’s American years, which paradoxically were at once a turning point in his artistic career, a moment of profound development, and a time of only limited artistic output. You trace three different phases of his exile: his arrival in New York, his military training in California and his participation to the war as an American soldier:

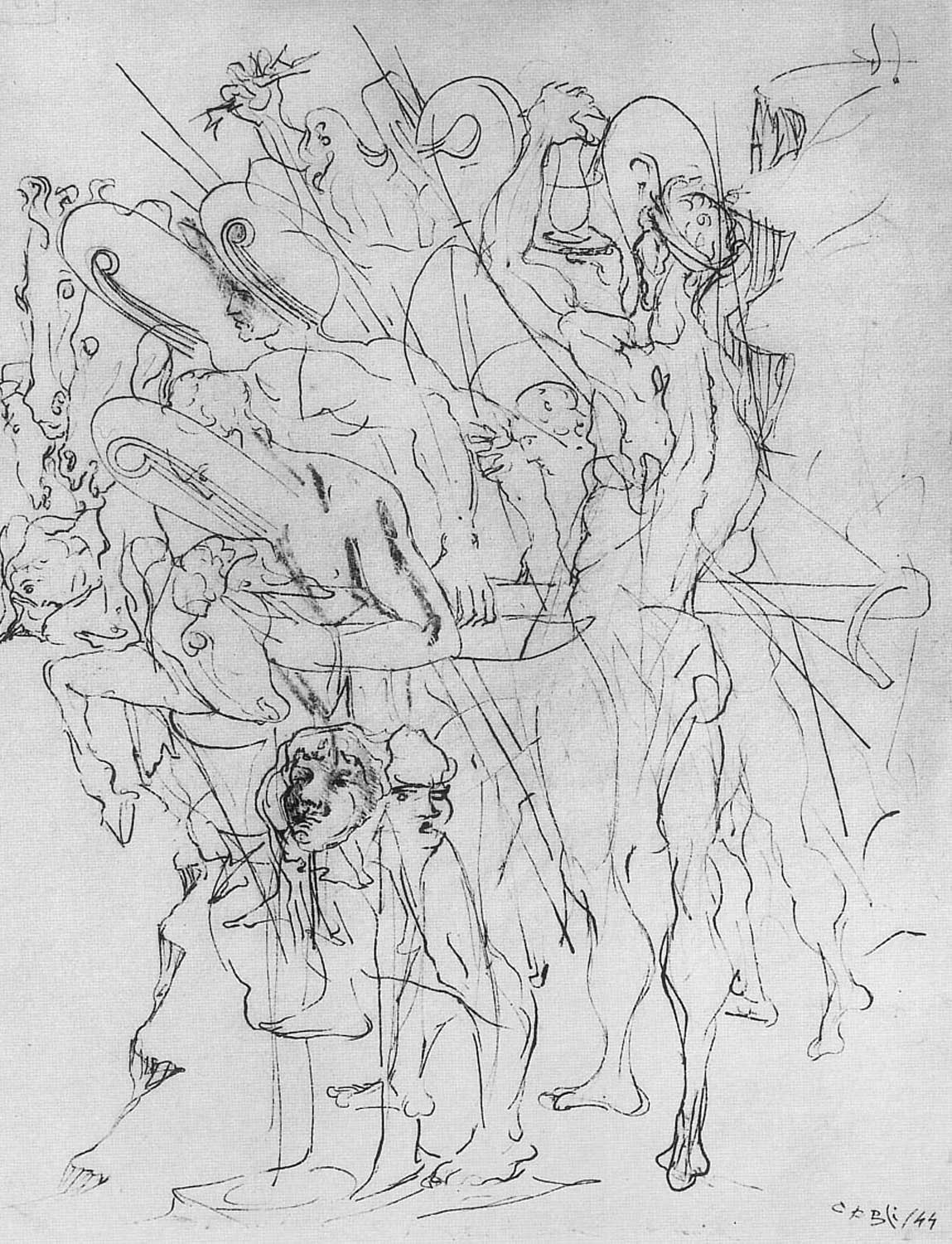

RB: Because of the frequent traveling and change of environment, inevitably the American years were not a time of intense production, compared to what came before and after. Among other things he rarely had a proper studio, which made painting difficult. In fact, most of his production in the US consisted of works on paper. I hypothesize that the reasons for working on paper were not only logistical ones but also, more importantly, the result of a crisis he went through with his idea of painting. Painting had been for him a largely public activity that has to do with a role within a collectivity and within a given society. In the 1930s Cagli saw public art as an essential tool to construct an Italian national identity in line with fascist ideology. During the exile we are left mostly with drawings and, if we were to evaluate them purely from the point of view of artistic result — and not also as traces of his artistic search— I would have to say, that some of them are pretty bad! Instead, they become extremely interesting if we look at them as proof of a profound existential and artistic disorientation.

AC: Thumbing through the many reproductions in the book one is stricken by the variety within the drawings.

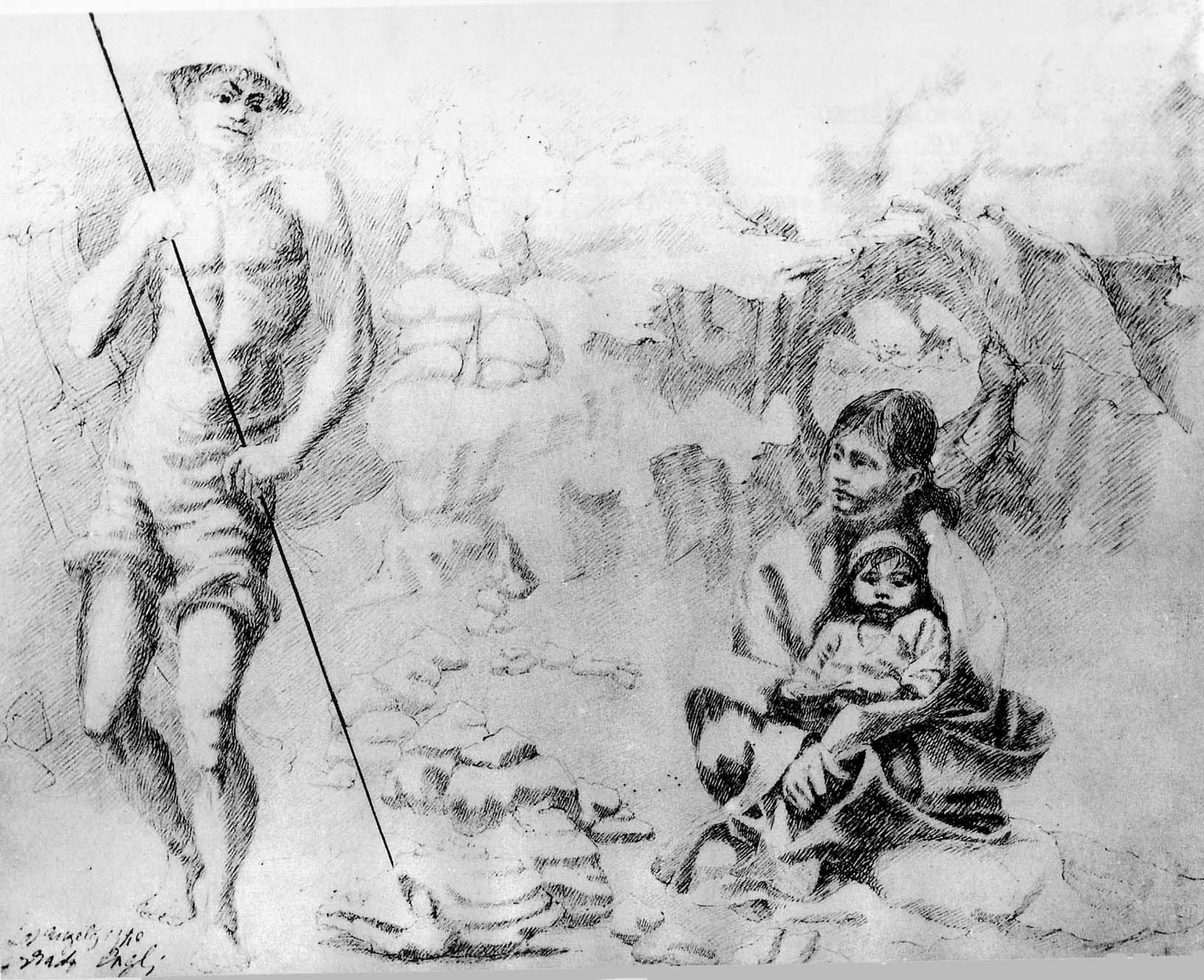

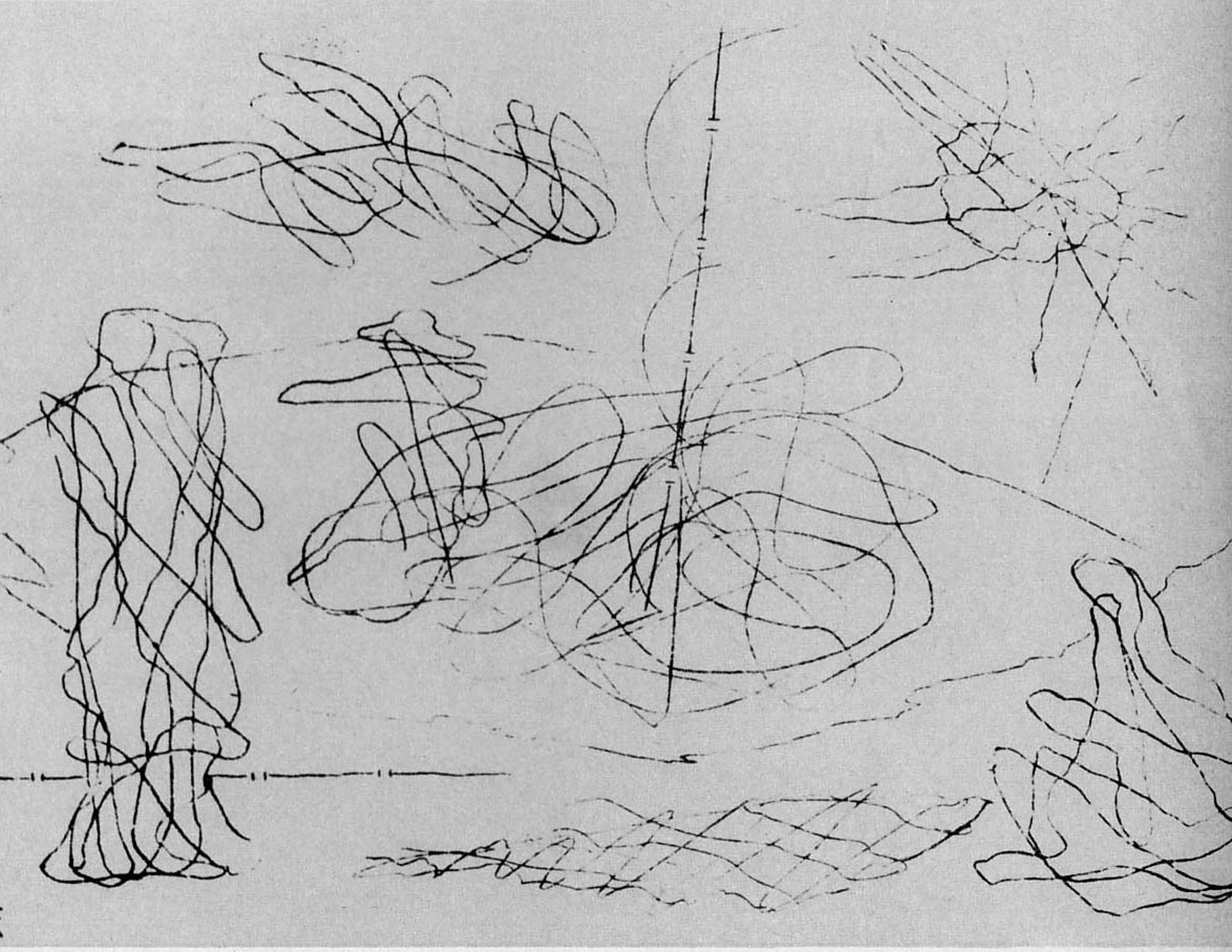

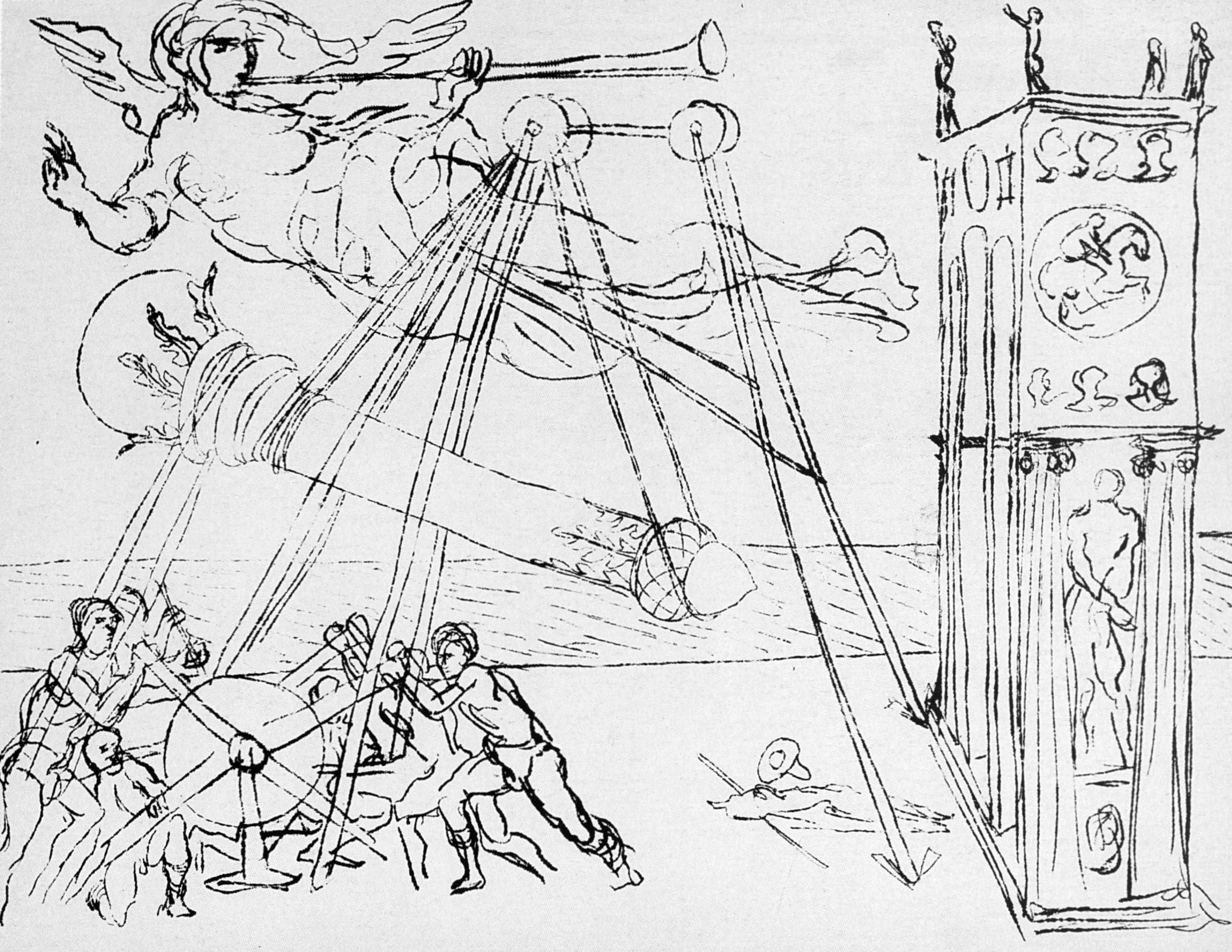

RB: They are totally diverse: you have a Dada-like collage (fig. 2) next to drawings that look like High Renaissance or Baroque (fig. 3), and then works I would define as almost Surrealist (fig. 4).

He also invented a technique similar to monotype where he would apply oil paint onto a sheet of paper, draw with a metal point on another sheet, placed on the oil paint facing up, so that the drawing would appear on the verso side, thus he would draw “blindly” without seeing the result until the end. The Surrealists would call it automatism. Some of these are very surprising works, often subverting the rhetoric of power and of a glorious past. They also have a strong homoerotic component, which subverts the macho heroism of fascist iconography (figs. 5-6). They are not explicitly anti-fascist, but definitely, they show a crisis in his idea of continuity with the past. My students at Cooper Union were blown away by these.

AC: You write in interesting ways about, how while he was trying to re-define his role as an artist, drawing becomes the center for everything else and then continues to be a through-line in his oeuvre.

RB: He had always valued drawing as an art form, and in exile, this became so important as to become the primary instrument of artistic search.

AC: The more one studies the history of exiles from this period, the more one is inclined to conclude that, beyond some general shared experience, often each individual perceived and inhabited the condition of exile in a specific way. From Cagli’s correspondence one gets the feeling of how important it was for him to maintain a tie with Italy, and yet soon he seemed unable or unwilling to communicate even with his closest friends there…

RB: Yes, even the relationships that had been central to his life in Italy, for various reasons could not be kept alive through letters. He expressed a strong sense of nostalgia and loss, yet ultimately realized that he could not accept what his friends were describing to him from Italy, and in turn the impossibility for him to share his new experiences with them. He now resented the fact that his friends’ production fueled the propaganda machine of the regime.

AC: In New York, among people of all kinds he met many Jewish exiles from other European countries, often with very different experiences and outlooks.

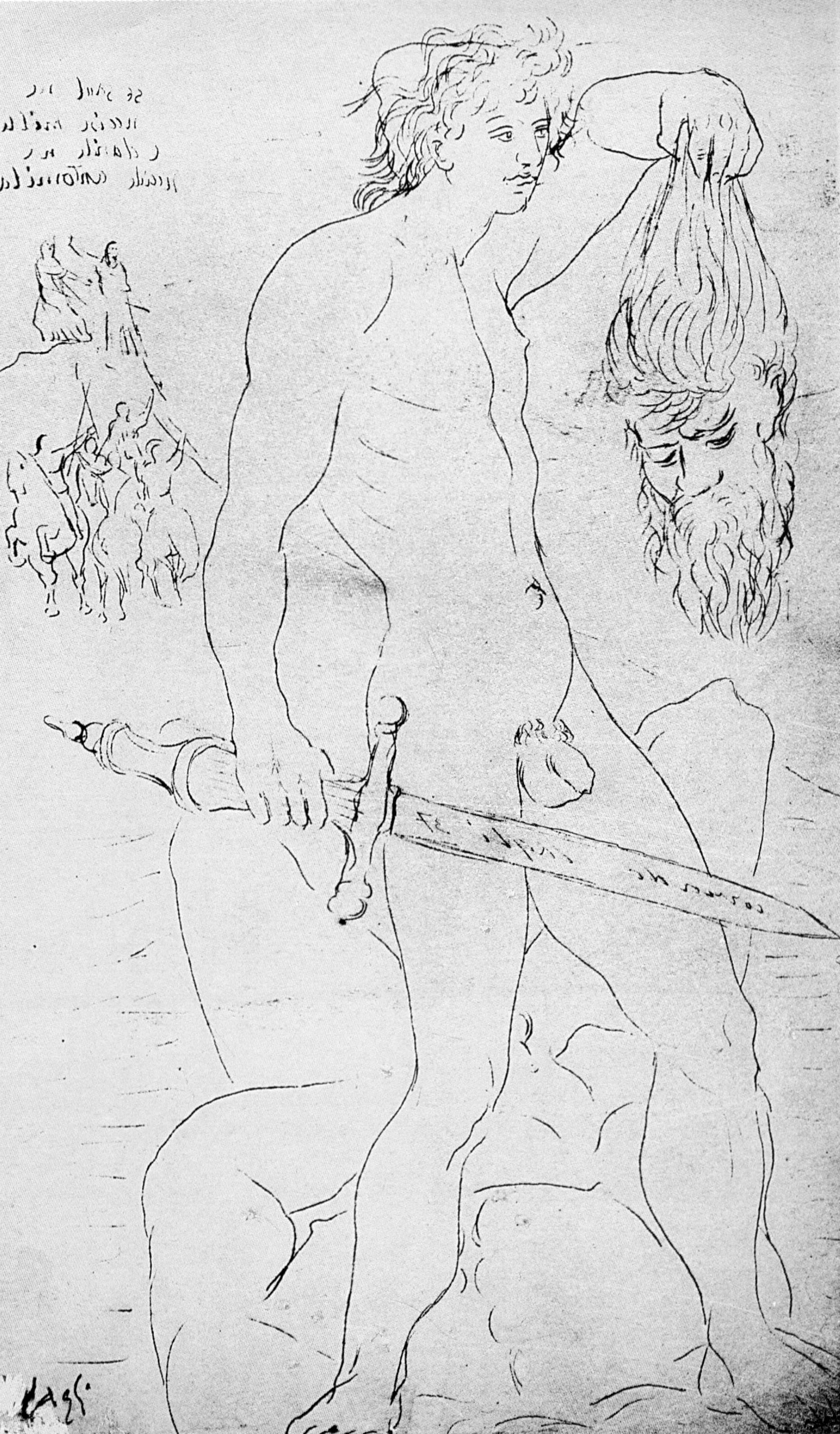

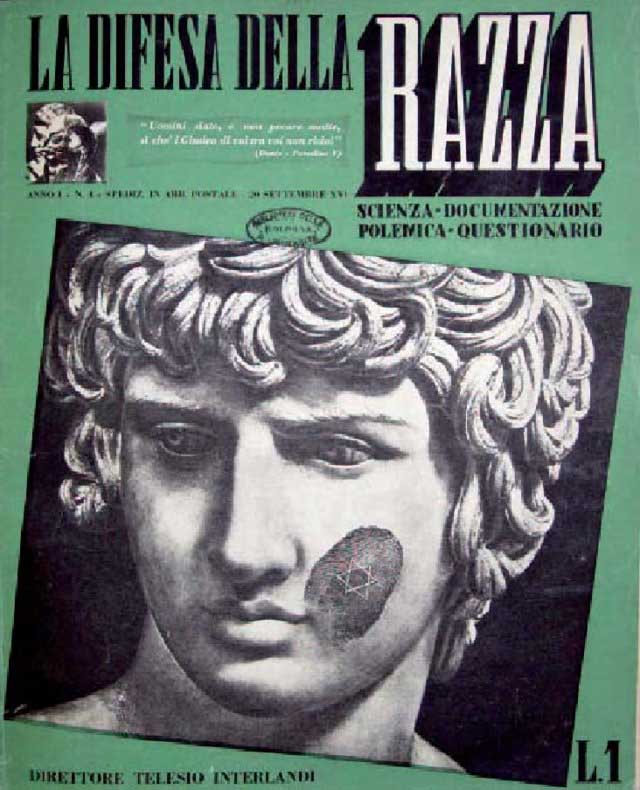

RB: Like many Italian Jews, Cagli —who was born in Ancona and moved to Rome as a child— had the experience of growing up in a largely assimilated secular family, who had dramatically come to terms with its Jewishness, starting in 1937 as antisemitism became more and more aggressive. For one, he represented obsessively scenes of David slaughtering Goliath, in a moment when the star of David became a tool of discrimination in Italy (figs. 7-8). As part of a series of books curated by Renato Camurri which focus on Italian exiles, my work on Cagli contributes to a larger project. By exploring this understudied subject, Camurri’s series emphasizes the specificity that characterized the experience of the exile for the Italians as opposed to better known phenomena such as the exodus of French or German intellectuals. But it also explores the great variety of individual experiences under the umbrella of Italian exiles.

AC: Throughout the book one gets the sense that Cagli thought deeply about what exile meant to him, coming up with some surprising intuitions. One of them was seeing exile not only as a loss of context but also as an opportunity to be “diverso e migliore” (different and better)…

RB: Cagli had had a remarkable, and I would say even too easy early success in Italy. In the early 1930s —he was only in his 20s— he was already famous nationally. Further, he was chosen to represent Italy at the expo in Paris, the Venice Biennale, and other prestigious expositions. He had been truly a phenomenon. Thus when he was exiled from the country and society he had represented, this inevitably caused a major crisis. He was forced to redefine his relationship with the collectivity, with his sense of belonging. Depending on the moment, he saw this with optimism as an opportunity to re-think the public role of an artist. But he also had moments when he saw any form of artistic production as solipsistic and therefore irrelevant.

AC: Fascist Italy rejected him as a Jew and as an artist, but from what you write it appears that he did not actually reject Fascist Italy’s artistic ambitions.

RB: Interestingly Cagli never rejected that idea of Italianità, despite having been forced into exile. He hanged on to that concept when he found himself in America, even when he was an American soldier fighting against Italy. He retained this idea of Italian culture, of belonging to that tradition and of thinking of Italy as a nation. Yet his correspondence with his sister, Ebe, who had also left Italy after the Racial Laws and was a student at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, switched to English very soon after their arrival.

AC: Repeatedly he wrote about conceiving of himself as an Italian painter, and unlike some other artist in exile, he never imagined or wanted to be anything other than that.

RB: Yes, he continued to hold on to that identity, but now in a new context. He saw himself as an Italian artist and thought of painting as Italian art! He wanted to figure out how to be an Italian painter in America, so we see him struggling to assert himself through his painting while in New York, Baltimore or on the West Coast.

AC: Can you give me an example of how this played out?

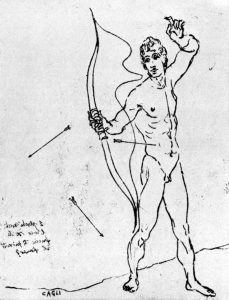

RB: In New York, he initially showed at the Julien Levy Gallery. Julien Levy was the one who brought Surrealism to the US so, for Cagli showing with him was a significant change and a chance to be in contact with a whole new set of artists working here. The show is not well documented, but I believe that he exhibited those blind monotypes described before. They include absurdist allegories or classical-looking figures acting self-destructive gestures –for example, an archer shooting arrows onto his own body (fig. 9).

He kept on drawing during his draft as he moved from California to Washington State and Oregon. There he drew biblical figures and mythological heroes wandering through the American landscapes as if they had got lost. He also executed at least two cycles of “mural” paintings (he used this term) in the military barracks where he was stationed, but unfortunately, those works are lost or at least I was not able to locate them, though there is some photographic documentation (fig. 10).

AC: You describe his conception of a sort of non-monumental mural technique…

AC: You describe his conception of a sort of non-monumental mural technique…

RB: While in California he acknowledged that at that time the Mexican school of mural painting —Diego Rivera— had become dominant.

One must remember that muralism was a major movement in fascist Italy. The idea, basically, was that painters should do public art by painting monumentally on walls, and Cagli had been a leading figure. So in California, his dilemma was how to present himself as a distinctly Italian mural painter without falling into the suspicious category of fascist bombast.

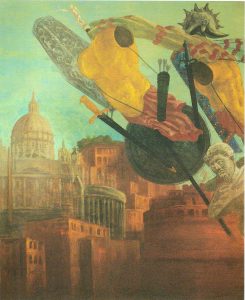

He developed the concept of a “portable mural” that could be dismounted, folded and carried in the trunk of a car. Thus an anti-monumental, transportable, temporary artwork… Long gone were the days when in 1930’s, under Fascism, he had written a manifesto Muri ai pittori! (wall to the painters!) tying into the idea of monumentality, eternal values, and bombast. Now, he was almost doing the opposite. In fact, I have to add that in the 1930s at least two of Cagli’s murals had been censored by the same government which had commissioned them because they did not fit with the regime’s rhetoric and stylistic preferences (fig. 11).

AC: How do you interpret this phase of his work?

RB: I think it can be seen as the assertion of a new nomadic artistic identity, and perhaps also as a device to defend himself from suspicion of still being linked to the fascists. After all, not long before Fascist Art had been promoted in California by the Italian government, so now as an American soldier, this placed him in an awkward position. On the other hand, as an American soldier, he had found a new sense of collectivity, although temporary, and produced a public work reflecting that condition.

AC: Cagli volunteered for the draft, what do you make of that decision, did it stem from a desire to go back and fight against Nazi-fascism?

RB: Indeed he “volunteered,” but I think that more than anything it was a shortcut toward citizenship, a way of legalizing his residence here. Yet I don’t want to minimize a choice that was dramatic. At first, I was surprised that he was not sent to Italy given that he spoke the language and knew the habits there: I tried to find clues to any efforts on his part to avoid fighting against his fellow Italians. But I could not find documents to prove that. Then I read that one of Cagli’s friends, Saul Steinberg, who spoke Rumanian, Italian, French, German, and some Spanish, was sent to China by the US Army and I gave up finding a logic!

AC: Both during his military training and later during the war, the US army recognized his artistic talent and allowed him to be a soldier/artist.

RB: During training he painted barracks, made illustrations for a military magazine, and created his own drawings exhibiting them in and out of the military context. Later during the war, he had an agreement with the Army, as a military artist. Many of the works that he did in London, during the landing in Normandy and later during the Allies’ advance into Belgium, and Germany, were exhibited as it were, “in real time.” On D Day, for example, as he participated in the landing and the combat, he had a show opening in London, which he, of course, did not attend. The American Army found in Cagli an opportunity to present an artistic perspective on the war they were fighting. Many of Cagli’s war drawings were made from his imagination, not from direct observation. For example, while in London, he drew scenes from the American campaign in Italy, in which he had not participated (fig. 12). Further, in some works, he mixed and combined scenes from antiquity, or from mythology with scenes of World War II (fig. 13).

AC: Perhaps he wanted to differentiate his work—always reflective— from any kind of war reporting…

RB: Not only was he not a reporter, but he was keenly aware of the major impact that the use of mass media reporting had on the war and on public opinion. On his part, we find a constant questioning on what the role of an artist wishing to represent the war. A war, which he saw as largely un-representable… I was puzzled by the fact that he made some of his drawings of Buchenwald before the US Army actually liberated the concentration camp in April 1945. Some of them, for example, where exhibited at the Whitney in New York in February. My hypothesis is that these were part of psychological warfare, like his drawings on the Italian campaign, which were published in London in Italian-language magazines and distributed throughout Italy (fig. 14).

AC: You make it clear that Corrado Cagli wished to express his artistic credo mainly through painting. Painting was for him participating in, and being in dialogue with, a long tradition of Italian art that started with the Renaissance if not before. However, in all phases and places of his life, Cagli also acted as a cultural organizer, a promoter of his own work and that of artists he believed in.

RB: Cagli worked in every possible medium: he did ceramics, mosaics, tapestries, monumental sculpture, architectural decoration, ballet scenography, and costumes. But he still placed painting at the top of any hierarchy. He also felt that an environment of like-minded individuals, or a school, was necessary for artistic creation. We see this clearly in his organizing role at Galleria La Cometa in Rome and in his relationship with the poet Libero De Libero. They created together an artistic circle, a cenacolo around the gallery as a necessary and supportive association of creative minds, putting musicians, writers, architects in dialogue with painters and sculptors. The term used at the time was that of a “synthesis of the arts.” Once in exile, his crisis had much to do with how to make art in isolation, that is without a cenacolo, or how to create a new one.

AC: One of the strengths of the book is the reconstruction of the powerful yet delicate web of relationships which Cagli created, sought, and maintained. His insistence that painting be un’arte conviviale, and his relationships with poets, musicians, mathematicians, and choreographers. One would not necessarily be able to trace this back simply from an analysis of his paintings, so by bringing a lot of this into focus, the books become also an intellectual biography.

RB: Indeed the first intellectuals he established strong relationships with when he reached the US were a writer, Charles Olson (fig. 15), and a mathematician, Oscar Zarisky. And after the war, he found himself at home in the environment of music and ballet, much more than that of painting.

AC: Before landing in New York, Cagli had spent a year in Paris.

RB: His arrival in Paris as an exile was certainly less of a leap in the void than when he later came to New York. He knew the city and many artists living there because he had been there before for long periods of time. Yet his previous experiences were completely different, he had been there as the young star painter from Italy, on official missions representing Italy in an international context that was conceived as a sort of competition among nations. Now, he arrived as part of a crowd of mostly Jewish and anti-fascist exiles, thronging hotel lobbies and foreign consulates. Clearly, this was new, difficult and must have stirred up complex feelings.

AC: Cagli never really abandoned a feeling of rivalry or competition with French artist…

RB: Like many Italians, he thought that the centrality of Paris in the modern art world overshadowed the neighboring Italian school. Even in the post-war period, he talked about how there was a great opportunity, as the center moved from Paris to New York, to promote Italian art somehow in opposition to the French schools. It is striking how his position echoes the rhetoric used by fascists cultural diplomats in the 1930s. The Fascist explanation —which Cagli clearly did not buy— was that Jewish art dealers who had the monopoly of American art had a predilection for French school thus neglecting Italian art. However, he too felt that Italy should claim some of the territories the French had conquered in the US, and definitely bought into the idea of cultural diplomacy.

AC: To some extent, he was successful in the promotion of Italian art in New York…

RB: Indeed. He facilitated the beginning of the Catherine Viviano Gallery which opened in 1950 and was mostly dedicated to contemporary Italian art, and before that, he was involved in the organization of MoMA’s 1949 “20th Century Italian Art”. Thanks to these initiatives and others, by the mid-1950s Italian modernism, enjoyed unforeseen popularity in the US. He truly believed that Italian painting had its own specific identity and its own path to modernity. On the other hand —and this what made Cagli very difficult to embrace in the post-war period— he rejected the dominant idea of tabula rasa. Italian artists and society at large felt that after the war, one could and must start from scratch. Cagli instead refused to see the war and even fascism as an interruption or a parenthesis and was opposed to Benedetto Croce’s notion of fascism as something essentially foreign to the Italian tradition. Cagli believed in the dynamic stratification, layering, and complexity of history: a sequence of events and occurrences, where he saw more continuity than ruptures.

AC: After the war, Italian society was attempting to whitewash its recent past.

RB: Yes and in that context, after the downfall of fascism, everyone spoke of a new Italian Renaissance which for Cagli was merely a rhetorical stance.

AC: This must have something to do with his desire to not to renegade his work from the fascist era…

RB: Unlike some other artist he never rejected his earlier work, absolutely not!

By contrast, Lucio Fontana, who had spent the war years in Argentina, adopted the strategy that a new era had begun when he returned to Italy in 1947. He ultimately embraced the tabula rasa idea. He had himself photographed in the rubble of his former studio that had been bombed by the Allies. Under those rubles laid symbolically the work he had done in the fascist era. Cagli did the opposite: he too found his former studio bombed, yet together with other artists he dug out the paintings from under the rubble and exhibited those works. Further, in the 1930’s, he had painted murals in the headquarters of the Associazione Nazionale Balilla, the fascist youth organization, which had been censored. After the war he had them uncovered and presented them anew. Simultaneously, he published his war drawings made as an American soldier, depicting death, destruction, concentration camps … People didn’t know what to make out of this!

AC: Admittedly, it must not have been easy for the public nor for the critics to know what to make of someone who was both as you say reclaiming work that had been commissioned to him by the Fascist state and exhibiting drawings he had done as an American soldier of the horrors of Buchenwald…

RB: And in fact, upon his return, Cagli stirred heated controversy as I explain at the beginning of the book.

AC: While some artist had been forced into exile before having found their artistic voice and found it in exile, Cagli in 1938, though young, had already been celebrated as one of Italy’s most influential painters. Perhaps this was an even greater weight to carry…

The book begins with the fistfight and heated polemics that surrounded Cagli’s first post-war exhibition in Rome. This, in a sense, exemplifies how during the American exile years, the artist and his country had moved away from one another in perhaps irreconcilable ways. Corrado Cagli had been forced into exile at an early age when his career was blooming…

Do you think his early success under fascism both made his exile and his return more difficult?

RB: There is a letter that Saul Steinberg wrote to his friend Aldo Buzzi in 1946 or ‘47 where he said something like, “I saw Cagli in New York: he is gloomy, his past as a great Roman artist is a huge weight on his shoulders.” For sure, his fascist past was a problem. But the language of his postwar opponents was also filled with anti-American, anti-Semitic, and homophobic tones. Major fascist artists had no problem after the war in Italy. But Cagli’s return from the US was seen as threatening by many. He was the ultimate outsider.

AC: His decision to return to Italy was perhaps coherent with Cagli’s sense of himself as an Italian artist but came at a time when he seemed to be on the verge of an American career…

RB: After the war, there was a moment of favorable possibilities for Cagli here in the US. He had won a Guggenheim Fellowship, his work had been exhibited at the Whitney and MoMA, and he was collaborating with the New York Ballet Society. And yet that is precisely when he decided to go back to Italy. He still saw himself as an Italian painter.

AC: Why was his return so controversial, who contested him?

RB: He was heavily contested by… everyone! Older and younger artists — De Chirico on the one hand, the young abstractionists of Forma 1, on the other— took a distance from him or flatly rejected him, as did the most of the critics. Even many of his former friends did not know what to make of him and his work in the new context.

AC: In your book, you provide insight into the artistic and ideological complexities of post-war Italy, perhaps here we can outline more specifically one of the striking changes of mind, that of Giorgio de Chirico, who had originally opened up the American market for Cagli. How do you explain de Chirico’s original generosity and later fierce opposition?

RB: I think de Chirico’s original generosity, which manifested itself in the period 1937-1938, has to do with finding in Cagli a kindred spirit. They were both involved in with the Galleria Della Cometa first in Rome and later in New York. De Chirico, unlike the younger artist, already had a good group of gallerists and collectors in the United States, thus was in a position to introduce Cagli. Cagli’s work in turn somewhat reinforced de Chirico’s position. One should keep in mind that de Chirico’s reception was at a turning point. In America, all his work up to that point had met with critical consent unlike in France where the Surrealist group had famously rejected his post-Metaphysical work and considered his latest production reactionary if not Fascist. Thus de Chirico did everything he could to help the American market’s open up to Italian art and specifically to a route to modernity (like his own) that did not necessarily follow the path of the European avant-garde. Cagli presented exactly that kind of direction. Both were promoted as representing an alternative Mediterranean modernity, which established a relationship with the past through seduction on one hand, and of loss —in a Nietzschean sense— on the other. Cagli and de Chirico inhabited similar ideas of what an Italian way to modernity could be. They both had a great interest in the Baroque at a time when only few people paid attention to it, or in Delacroix and that kind of lush, painterly painting. So despite the differences in their respective work, they truly did have much in common.

AC: What changed later?

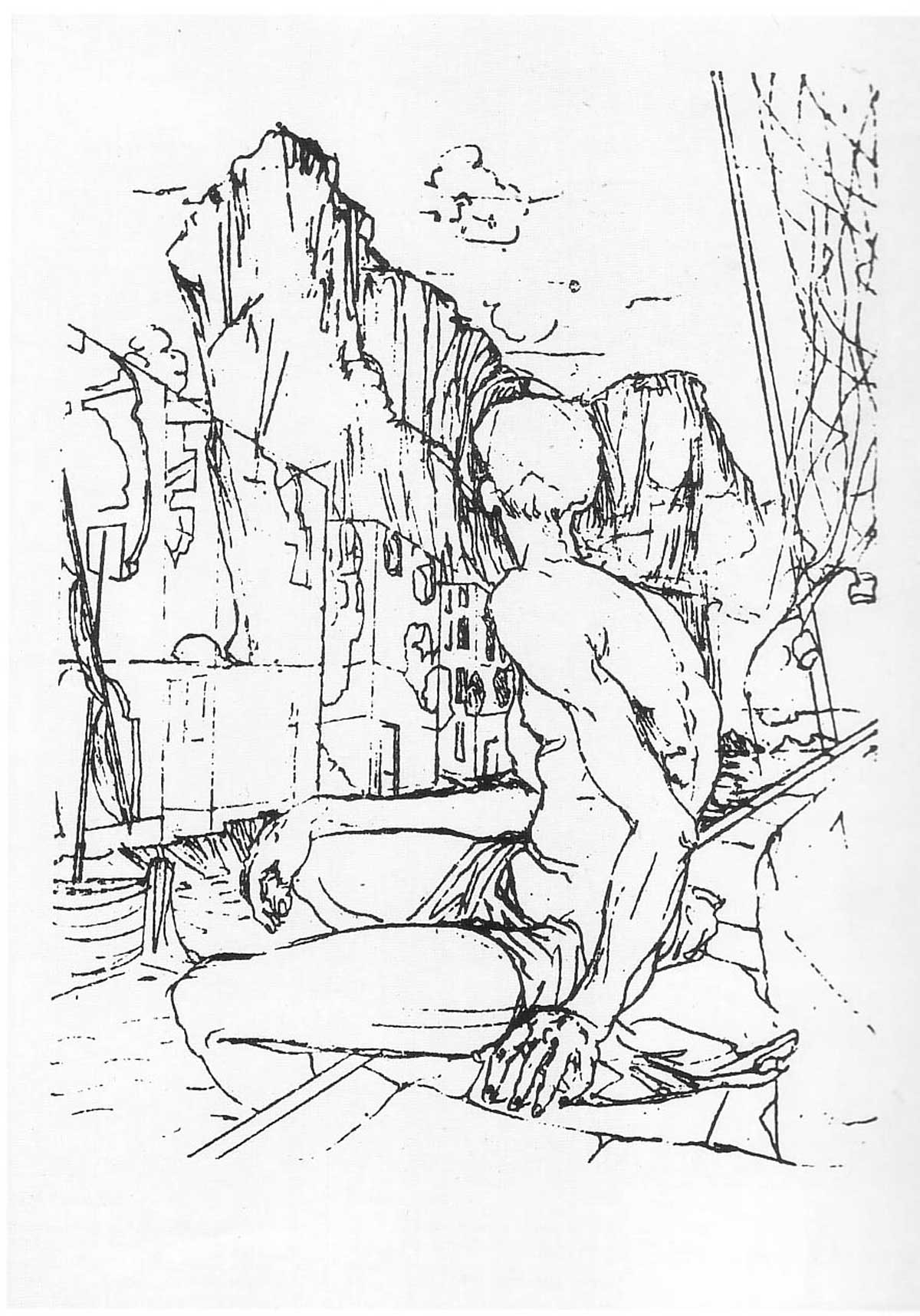

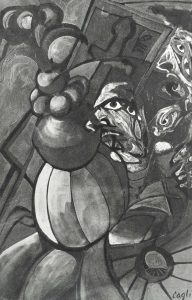

RB: After the war, Cagli goes back to Italy with the idea of a metaphysical avenue towards abstraction (fig. 16), as opposed to the neo-cubist trend which dominated postwar Italian painting —again he championed an Italian alternative to the French School.

While for de Chirico the very idea of abstraction was objectionable. And further, by then de Chirico saw America as hopelessly commercial. He was grumpy, disgruntled. He was suing institutions left and right, systematically authenticating false works of his, rejecting authentic ones and forging new “early de Chiricos” (now known as “verifalsi”)… It was at best an artistic project, questioning crucial principles and institutions of modernism, otherwise, it was simply a form of self-destruction… Cagli, on the other hand, supported a transatlantic dialogue with the American art world and presented himself as a leader of new forms of experimental art – a self-appointed role that most Italian artists refused to accept.

Images courtesy of the Archivio Cagli, Rome.

2- Collage, c. 1940, collage, cm 56×38.

3- The Window Rock’s Virgin, 1940, pencil on paper, inch 8,25×10, coll. Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut.

4- Da Galassi, 1939, oil on paper, cm 21×29.

5- Allegoria della fontana sbagliata (Allegory of the Wrong Fountain), 1940, oil on paper, cm 28×21,5.

6- Allegoria del trionfo (Allegory of Triumph), 1940, oil on paper, cm 28×21,5.

7- Davide trionfante (Triumphant David), 1937, oil on paper, cm 26×22. Inscription: “Se Saul ne uccise mille, Davide ne uccide centomila” (If Saul has killed thousands, but David hundreds of thousands).

8- La Difesa della Razza (cover), September 20, 1938.

9- Allegoria dell’arciere (Allegory of the Archer), 1940, oil on paper, cm 28×21,5. Inscription: “E perché scocchi l’arco se le frecce ti feriscono il fianco?” (Why do you shoot your bow if the arrows wound your side?).

10- Installation view of the show, Mural Paintings from the Day Room of the Battery B, 143rd Field Artillery Camp San Louis Obispo by Corrado Cagli, February-March 1942, M. H. De Young Memorial Museum, San Francisco.

11- Veduta di Roma (View of Rome), 1936-37, encaustic on board, cm 240 x 400.

12- Anzio, 1944, oil on paper, cm 29×23.

13- Termopili Normandia (Thermopylae in Normandy), 1944, oil on paper, cm 29×23.

14- The concentration camp of Buchenwald, 1945, oil on paper, cm 25,1×30,8, MoMA, New York.

15- Y & X, poems by Charles Olson, drawings by Corrado Cagli, cover, Black Sun Press, Washington D.C. 1948.

16- La Chançon D’Outrée (The song of Abuse), 1946, ink on paper, cm 30 x 22.