John Connelly, From Enemy to Brother. The Revolution in Catholic Teaching on the Jews, 1933-1965, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, 2012, pp. 365

The historiographical debate over twentieth-century European totalitarianism has been enriched in recent decades by new interpretative perspectives and documentation that have led to a deeper understanding of that period.

Historiographical literature has also paid a good deal of attention to reconstructing the events surrounding the Holy See, how the Christian churches had to come to terms with the advancing process of the Nazification of the European continent and the compromises and strategies for coexistence which resulted.

The same is true of studies dealing with the history of anti-Semitism, its Christian roots, and the fluctuations, in instances and practices, of its manifestation and decline during various periods of modern and contemporary history.

Faced with such a convoluted scenario with so many theoretical and thematic aspects and further complicated by strong overtones of controversy, sometimes more political than strictly historical, it has been difficult to find a book that can not merely broaden our knowledge of the period, but also proposes an original vision of it.

John Connelly, however, has succeeded in writing one of those rare books that combines a synthesis, never trite, of the events being narrated with a robust critical interpretation firmly anchored to the documents presented and discussed on every page of the book.

Its broad historical sweep offers an understanding of the events and protagonists from a long-term perspective, and imbues the narrative with sufficient depth and insight to leave the reader with many points on which to reflect further.

The first three chapters focus on modern racism as supported by – far from marginal – fringe groups of the Catholic Church; the thorny problem for the Church, when dealing with the “race issue”, of tackling the role played by science in defining and hierarchically classifying the races, as found in the writings of the theorists of European Fascism in the 1930s; and the ambivalence and reticence with which the Christian churches, including the upper echelons of the Vatican, reacted to the new doctrines of racial superiority that led to the Holocaust.

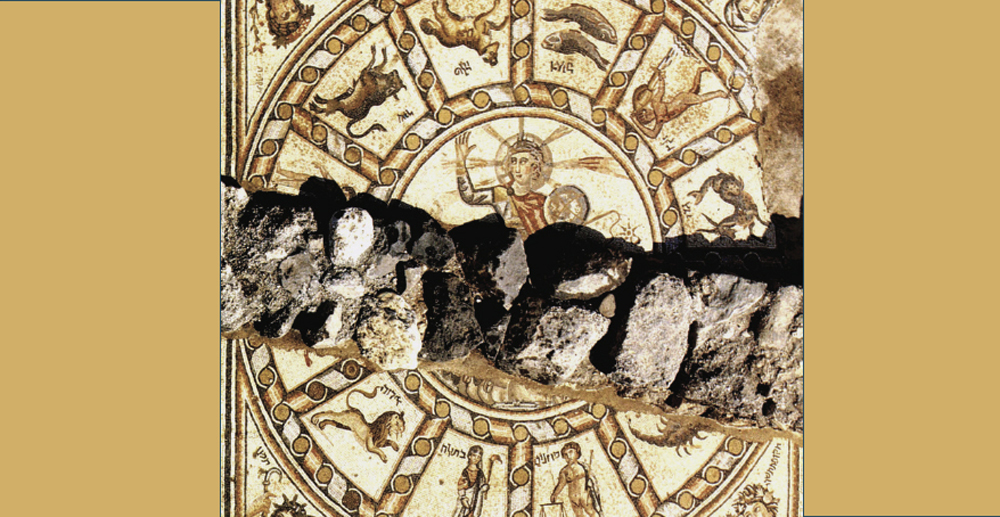

Ample space is given here to the role played by the Catholic Church not only as a political institution, but also as that symbolic place where the anti-Jewish fight originated. The theoretical plane of Christian anti-Judaism is in fact related to the evolution of the anti-Semitic practices which emerged in Europe in the nineteenth century: the Jew becomes a “rallying myth” both in the strictly political programs of right-wing political parties – even Christian ones; – and in the dynamics of the internal cohesion of socially disrupted strata or which perceived themselves to be such. –Forms of collective thought – the sedimentation of mental codes – aimed at expelling the Jew from the “healthy” body of the Race and the Nation, are recalled at intervals by Connelly to help unravel the tangled threads of a story, which has brutally demonstrated that Modernity does not necessarily correspond with Progress.

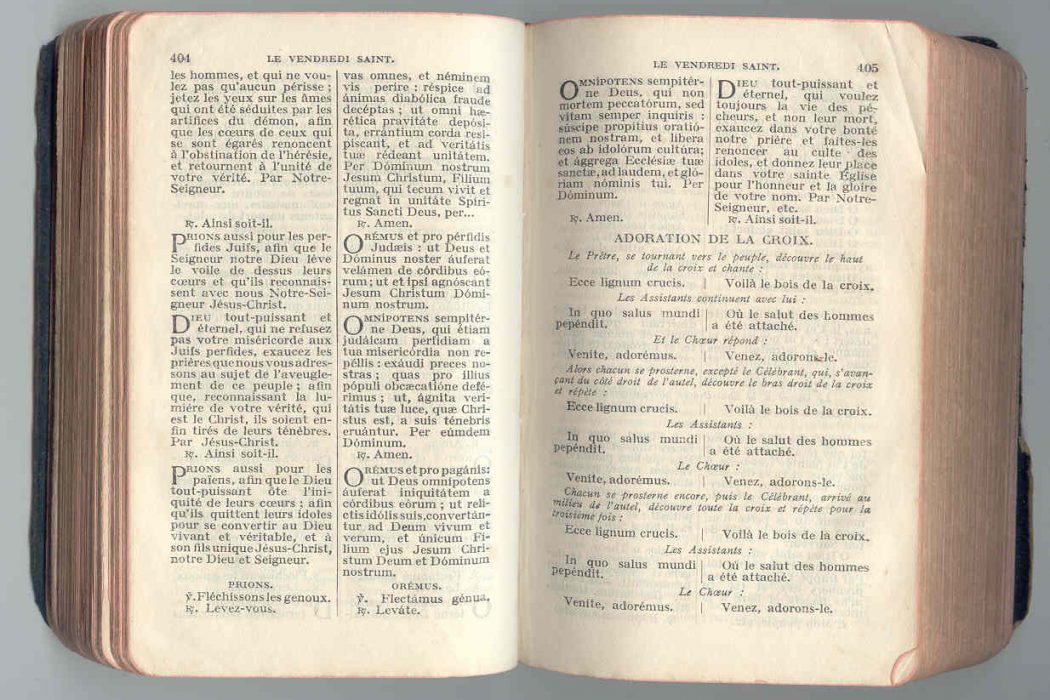

The paths taken by the Churches and their intellectual, as well as political, leaders, as regarded responsibility for the anti-Jewish teachings in the body of Christian doctrine, following the extermination perpetrated in the heart of Christian Europe, are reconstructed in the second part of the book which considers several matters that led the Catholic Church to ponder its anti-Jewish theologies culminating in the Second Vatican Council and the promulgation of that text, so central to the history of Jewish-Christian relations, the Declaratio Nostra Aetate. The Council text, dealing with the relationship between the Catholic Church and non-Christian religions, for the first time in the history of the contemporary Church, condemns modern anti-Semitism and establishes as a top priority the necessity of creating a dialogue with Judaism devoid of the Church’s traditional conversionist assumptions.

On this basis, the Church not only emphasized the spiritual bond it had with Judaism, recommending mutual understanding and respect, but notably absolved the Jews from the ancient accusation of being the “deicide people”, thereby establishing a fundamentally important turning point, one especially crucial in terms of catechesis.

Connelly’s narrative is not only diachronic. It moves engagingly back and forth, through a rapid succession of fragments of thoughts, ideologies, books written and rewritten, as well as individual reassessments, continually returning to what has been done and what can always be reshaped. Dialogues are interrupted and then reconnect in constantly heightened comparisons, confrontations and exchanges of ideas or prejudices that fully mirror and convey that flow of thought and time that so often does not coincide with that of history and its chronologies.

The geographical contexts through which the author leads us are also polycentric, ranging from Germany to Austria, France and Italy, from England to the United States of America. They are the places inhabited by the protagonists of the events recounted by the author. Locations of emigration and education: but also those interior spaces, which intimately explore the doubt, the awareness, the uncertainty, that continuous dialectic between faith and the immanence of history.

In an article published in 1983, Saul Friedländer posed a crucial question for all historians: “…the growing number of works, the accumulation of ever-more detailed knowledge, multiple attempts at interpretation, nevertheless leave an unanswered question: do the gains of historiography now allow us to place events in the framework of a comprehensive and coherent historical interpretation; or are we confronted by the fragmentary visions which defy any synthesis that is not purely descriptive and challenge a true understanding? “.

This book convincingly answers the question posed by Friedländer almost thirty years ago as it untangles those threads that connect individuals to the “big” events, adhering to the powerful idea that history is no mere list of data and information, but rather an open field in which interpretations clash, confront each other and enter a dialogue. The continuous and vital tension in snatched glances that gives added sense and meaning to the past for those who want to question it.