Gemma Vitale Servadio, I am Counting on You, on Everyone…

Eight Letter from Fossoli, 1944. With essays by Mirella Bedarida Shapiro and Marco Coslovich, CPL Editions Memoirs & Biographies

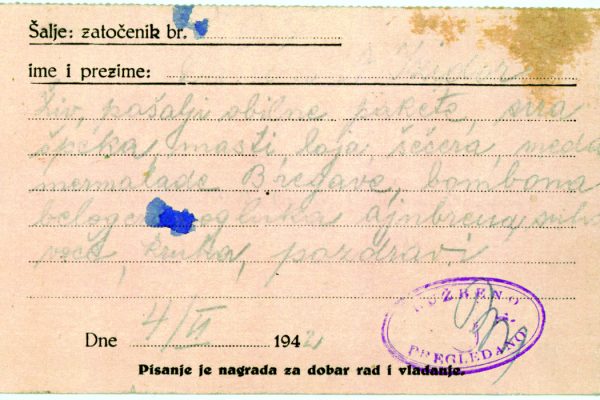

June 14, 1944.

My dearest, if this reaches you, keep the enclosure and give it to E. as soon as possible. After the first kind note from Gianna’s father, I have not received news from anyone. I would like news of him, Gianna, and Sandro. We have had no help from anybody, neither packages nor money, which we need so badly. Check with Arturo, Mrs. Masi and Mrs. Pollo. Arturo will know something about the house and our belongings. We are weak, it’s so hot.

I’m counting on you, on everyone, especially as regards Mamma. She is my greatest worry. If I were on my own I would be stronger and freer. Send some raggedy old clothes for me and for Mamma, for later on, too.

Thank you for everything — everything.

Hugs,

Gemma Servadio

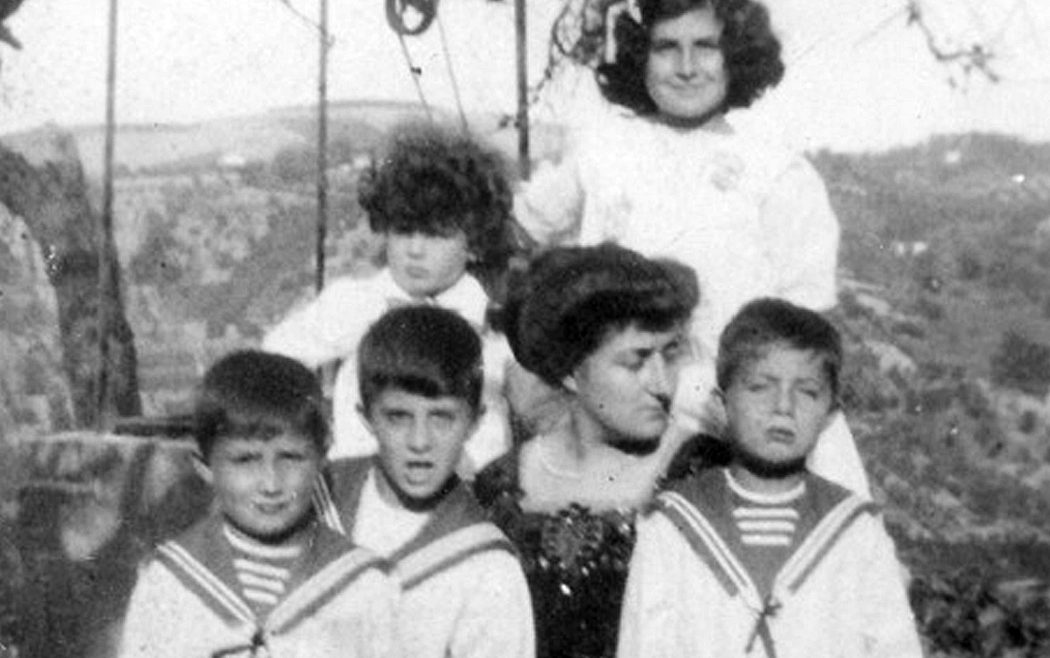

Gemma Vitale Servadio was born in Turin in 1878 into a middle-class Jewish family. When the Racial Laws were enacted she had the choice of moving to Brazil, where her son Luchino was living, or to Tangier where her daughter Lucia and family had found refuge. Not wanting to leave her 87-year old mother, Nina, alone, she stayed behind and moved in with her.

In May 1944 Gemma and her mother were arrested in their home in Turin and sent to Fossoli, the main internment camp in Italy. From there they were shipped in cattle cars to Auschwitz, where they were both gassed upon arrival on June 30, 1944.

This book presents the eight letters written by Gemma Servadio from Fossoli that have come down to us, curated by her granddaughter Mirella Bedarida Shapiro, with a an essay by historian Marco Coslovich.

The letters Gemma Vitale Servadio wrote from Fossoli between late May and late June 1944 are not just historical documents, nor are they a mere testimony of a traumatic physical and psychological experience.

Gemma’s letters are hard to compare with anything else because they’re so simple and bare, yet not at all elementary.

The letters are perforce obscure, allusive, evasive. And yet, throughout, there’s also an urgent need to make concrete requests. The names that appear in these letters are those of Aryan friends or people she knows have fled — in other words, people who wouldn’t be put in any immediate danger if named. All in all the writing of these letters was like playing a difficult game of chess, pressured by sheer necessity.