Il Generale della Rovere an the Dilemmas of Post-War Italy

In his recent book The Holocaust in Italian Culture, 1944-2010, Robert Gordon refers to the late 1950s and early 1960s as an age providing ‘something of a step-change in attention to the Holocaust. Cinema played a role in this shift, heralded in 1959 by Roberto Rossellini’s Il Generale della Rovere, which spearheaded a cinematic revival of films set during the crucial years of the Second World War, and more specifically within the Resistance in Nazi-occupied Italy. Some of the films produced in the early 1960s engaged directly with the theme of the Holocaust, as in the case of Kapò (Gillo Pontecorvo, 1960) and L’oro di Roma (Carlo Lizzani, 1961).

More often than not, they touched upon it more obliquely, just as Rossellini’s film did. Il Generale thus provided a template for a form of engagement with the persecution of the Jews in Italian cinema, one that situates the Jewish plight into the broader canvas of Italy’s response vis-à-vis the conflict and the occupation. It is the model followed, for example, by La lunga notte del ’43 (Florestano Vancini) and Tutti a casa (Luigi Comencini), both released in 1960. If Il Generale is significant in the history of Italian cinematic approaches to the Holocaust, it is then worth asking what response it engendered upon release. What did reviewers see in the film? What did they make of its relatively understated references to the persecution of Jews in Italy?

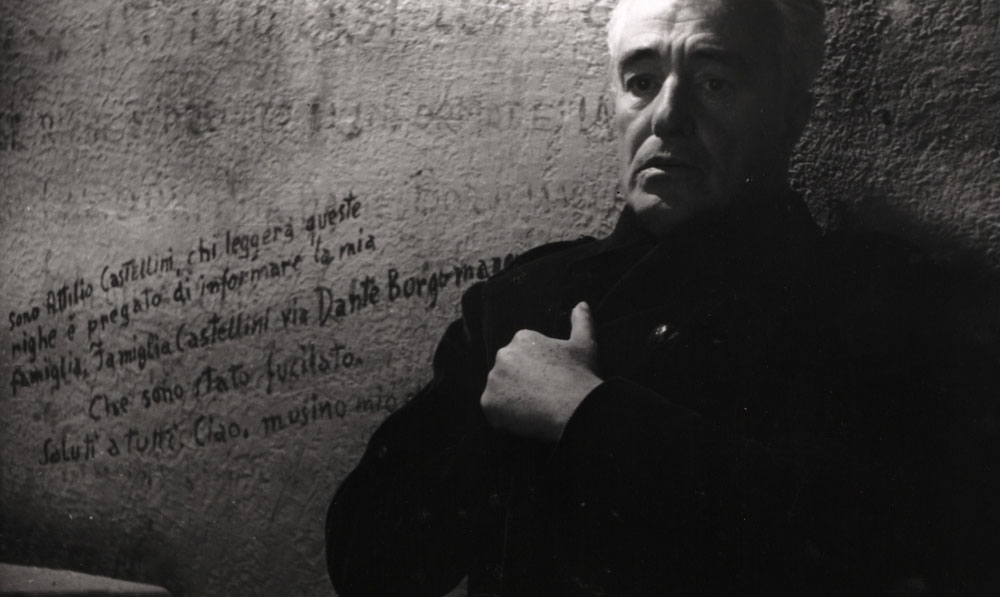

Set in Genoa in 1944, the film is the story of a swindler, Bardone, who presents himself as a retired colonel with the right connections with the German hierarchy and makes a living out of deceiving the needy relatives of those who have fallen prey to the Nazis. Arrested by the Germans, he is offered a deal that would save his life: he must assume the identity of General della Rovere – a highly respected leader of the Resistance killed by the Germans, serve time in the San Vittore prison in Milan, and identify other leaders held in custody. Bardone accepts the life-line offered. However, exposed to the dignity and determination of the real resisters, he experiences a metamorphosis, conducting himself as if he was the real General. As a reprisal for a partisan action, the Nazis decide to execute a number of prisoners. As a way of forcing Bardone/della Rovere to reveal the identity of the other leaders, his name is put on the list, along with Jews, petty criminals, and antifascists. Willingly accepting his fate, the spurious General dies crying ‘long live Italy! Long live the King!’

Il Generale della Rovere premiered at the 1959 Venice Film Festival, winning the Golden Lion. It became the eighth-highest grossing film of the season in Italy. It was immediately hailed by commentators as a return, for the director of Roma città aperta (Open City, 1945) and Paisà (Paisan, 1946), to the themes that had made him an acknowledged master, as a sign of the re-launch of Italian cinema after years of disengagement, and a reaffirmation of the moral value of the Resistance.

The communist party house newspaper l’Unità eulogised the film for telling the story of a morally despicable character who is redeemed by his encounter with the morality of the Resistance. The newspaper’s only criticism was that the film’s focus on a cynical trickster put the positive characters (active subjects in Roma città aperta) in the background. Despite communist emphasis on the Resistance, the novella by conservative journalist Indro Montanelli on which the script was based downplayed the role of the Resistance, focussing instead on the morality of military values. Thus, the film’s origins comprised of mixed political orientations, as testified by the writing credits, which include Montanelli himself, Diego Fabbri, and Rossellini’s communist long-time professional partner Sergio Amidei.

The element of compromise that characterises the film accounts for the praise it received from diverse quarters, according to their different readings. The Catholic press discarded the theme of the Resistance in favour of a universalising defence of human dignity. For example, the magazine Letture claimed that Bardone was moved to change his conduct by his identification with the role he was playing, rather than by his encounter with the morality of the Resistance, so depriving his ‘conversion’ of any political value.

Following the same line of interpretation, the Office Catholique International du Cinéma (International Catholic Organisation for Cinema, OCIC) awarded the film its yearly prize on the grounds that it was the story of a sinner who redeemed himself, while the historical setting provided only the backdrop.

The same interpretation led to criticism from non-communist left-wing commentators. The socialist paper Avanti! criticised the character’s conversion for being the mere result of an emotive reaction, and therefore weak in political terms. The intellectual Franco Fortini articulated this critique still further. In Fortini’s penetrating reading, Bardone acknowledged no political value to the Resistance other than the courage of its members. In his eyes, the film transformed the Resistance into a morality play based on a conversion to good and self-sacrifice, at the same time noting that the fascists also sacrificed themselves, and were nonetheless wrong.

In other words, while the communist press read the film as a step towards legitimizing the Resistance, others saw it as a whitewashing of its value. The issues at stake in Fortini’s critique were further underlined by film scholar Pio Baldelli, who observed that the film’s ecumenical patriotism leveled fascists and antifascists, portraying them all as Italian victims.

In fact, fascist collaborators in the film were often presented by reviewers as little more than poor ‘devils’ who struggled just like everyone else. To some extent the Germans were also portrayed in ways that differed from those characteristic of the early days of neorealism. As a group they were cruel but, ironically, SS Colonel Müller’s sophisticated manners and humanity gave him an edge over many other characters. The non-Italian journal Film in Review picked up on this ambiguity. The journal defined the film a symptom of Italy’s ideological confusion, whereby all Italians were good (whatever side they were on), and only Nazis were left to play the part of the ‘bad guys.’ But, since the Cold War political agenda demanded a benevolent approach towards Germany (as opposed to communist emphasis on the continuities between Adenauer’s government and the Third Reich), the Generale della Rovere produced a portrait of the ‘good German.’

Bardone himself was seen by many commentators as cunning but ultimately a selfless character (even though early in the film we see him in such actions as trying to sell a fake sapphire claiming it belonged to a rich Jewish lady on the run).

A number of reviews focused on the character’s display of ‘Italian’ vices turning into virtues, a recurrent theme that came to prominence many years later with the miniseries Perlasca: un eroe italiano (Alberto Negrin, 2002).

The Catholic Avvenire d’Italia and the conservative il Resto del Carlino seconded the film’s praise of the heroic Italians who, even when morally corrupt, allegedly never lose sight of their dignity and humanity. These interpretations of the main character’s personality led to numerous piqued responses on the left, which rejected his role as a symbol of Italy and saw him as a sign of Italy’s moral decline in the 1950s.

Thus, a 1959 film about the Resistance was widely seen as being at the same time historical and political. In this politicised reception, the hints made in the film to the specific sufferings of the Jews often went unnoticed. Such was the case of the long sequence leading up to the executions. The designated victims are Bardone/della Rovere, a few partisans, some suit-wearing profiteers, and a number of Jews. Reviewers did not notice the film’s reference to anti-Semitic prejudices that came in the shape of an allusion from one of the profiteers that there was some justification for not only the partisans, but also the Jews to be executed. Instead, reviewers identified another episode from the same scene, showing Jewish and Christian prayers merging shortly before the execution, as being among the film’s highlights. However, in this case, the Jewish presence went unnoticed. The Catholic Rivista del Cinematografo defined the scene as a sign of the authentic religious message of the film, while l’Unità bypassed the religious theme and referred to the motley crew of prisoners in terms of ‘comrades’ of the ‘patriots’ (i.e. partisans).

As stated at the outset, the success of Generale della Rovere, ironically a film that Rossellini himself saw as ‘commercial’ and somewhat embarrassed him, set the tone for a slew of films set during the Second World War and the Resistance with more than twenty in the three following years. Two of the ones engaging with the persecution of the Jews, the aforementioned Kapò, and La lunga notte del ’43 premiered at the 1960 Venice Festival, with the former becoming over the years a contested classic in the sub-genre of Holocaust films. Almost unintentionally, and without much of public opinion paying attention to it, Il Generale opened a new chapter in Italy’s Holocaust filmography.