Lorenzo Da Ponte in New York City

Anyone consulting the mid-nineteenth century catalogs of New York City’s two oldest libraries would be struck by the astonishing number of Italian books recorded. There are as many works of Italian fiction listed in the topically arranged 1839 Columbia College catalog as there are works in all other literatures combined, including English. In this manuscript catalog, “Romaic, Latin, Spanish, French and English” fiction constitutes a single group while the Italian entries are so numerous that that language merits its own category. In 1838, a disproportionate number of Italian books are also entered in the printed catalog of the New York Society Library. Did Italian studies really rank so high among Columbia College students and members of the New York Society Library in the 1830s?

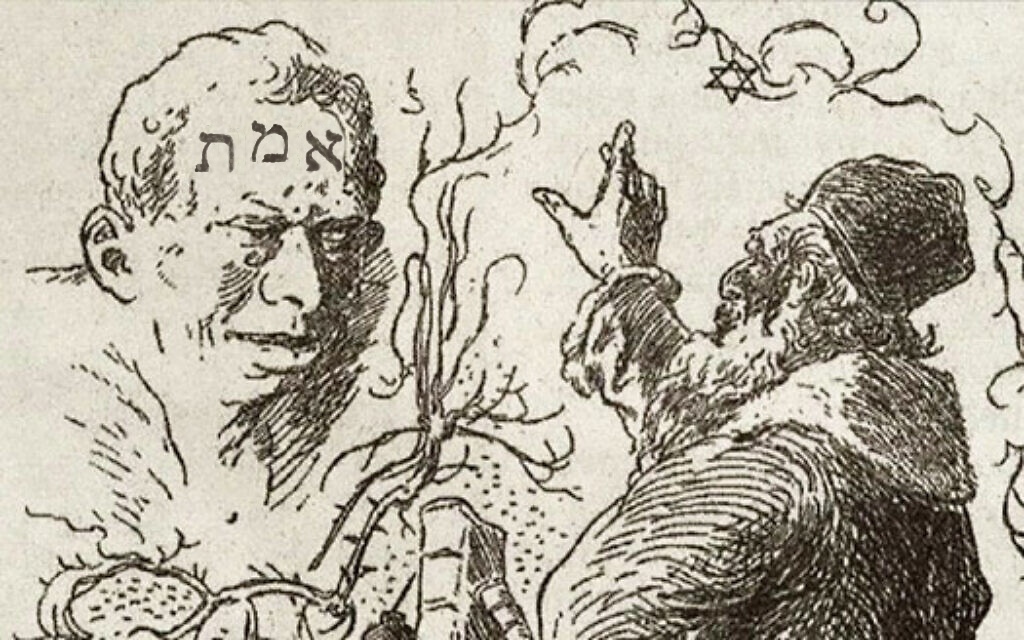

This unexpected surge of interest was the result of a single-handed crusade by Lorenzo Da Ponte to introduce Italian culture to America. Remembered today as the librettist of Mozart’s most famous operas, his was one of the most picaresque lives of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, perhaps rivaled only by that of his friend Giacomo Casanova. As Professor Joseph Russo of Columbia’s Italian department wrote, “Seldom, if ever, indeed, had a man of more interesting personality come to these shores from Europe.” Born in 1749 near Venice, he was the son of a Jewish father who converted to Roman Catholicism to remarry.

Da Ponte’s young manhood was spent attending seminary, taking holy orders, teaching literature and writing librettos. Despite these respectable pursuits, by 1779 he was living such a dissolute life in Venice that he was charged with adultery and banished from the city. It was in Vienna in 1782 that a well-known incident occurred involving his teeth. Suffering from an abscessed gum – the story goes – Da Ponte sought relief from Dr. Doriguti, a physician who had fallen in love with a woman who preferred Da Ponte.

Seizing this opportunity to eliminate his handsome rival, the doctor prescribed a mouthwash of nitric acid. Within a week, every tooth in Da Ponte’s mouth had fallen out.

Notwithstanding the loss of his teeth, the Viennese years were the most productive of Da Ponte’s long life. He was named “Poet of the Italian Theatre” to the Hapsburg court of Emperor Joseph II, which led to a partnership with Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. That evolved into “one of the most successful collaborations in opera history.” With Da Ponte writing the librettos, Mozart composed his greatest operas, The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni and Cosi fan Tutte. When Joseph II died in 1790, Da Ponte lost a patron and protector from the intrigues of the court. “Sacrificed to hatred, envy, the interests of evildoers;” he wrote in his Memoirs, after the partnership with Mozart had ended, “driven from a city where I had lived on the honourable earnings of my talent for eleven years! Abandoned by friends.” Mozart’s disgraced collaborator surfaced in London in 1793 where he operated an unsuccessful shop specializing in Italian books.

By 1805 he was financially ruined and facing debtors’ prison. Da Ponte fled to America where he hoped his run of bad luck had run its course. The foremost librettist in the world began life in the New World as a grocer in Elizabeth, New Jersey.

A chance encounter with Clement Clark Moore in 1807 launched Da Ponte’s career in New York. Moore was the Professor of Oriental and Greek Literature at Columbia College, and he met the urbane grocer at Riley’s bookshop on lower Broadway.

They fell into friendly conversation, and Da Ponte impressed Moore with his easy familiarity with the classics and fluent Hebrew and German.

The professor soon learned that in addition to Da Ponte’s numerous talents and accomplishments, he was also personally acquainted with many of the most cultivated men in Europe. A friendship quickly ripened between the two men, and with introductions from the socially prominent Moore, Da Ponte was soon being lionized by the literary elite of the city.

After devoting a few years to teaching private classes in Italian, in 1825 Da Ponte won an appointment at Columbia College. At the age of 76, he became America’s first Professor of Italian.

1825 was the watershed year for Italian studies in New York. When the Italian Opera Company arrived in the city that year, the just appointed professor organized and promoted the first operas performed in America. Taking advantage of the quickening enthusiasm for all things Italian, Da Ponte established a relationship with the New York Society Library and founded the Italian Library Society there. In May of 1827, Da Ponte announced that he had placed some 600 books in the Italian library and expected to add another 400 when they arrived from Europe, the whole to contain “the flower of our literature in all the useful arts and sciences.” A list of these books can be found in the Catalogue of Italian Books, Deposited in the N. Y. Society Library for the permanent use of L. Da Ponte’s Pupils and Subscribers (New York, 1827).

Forty-six “Subscribers to the permanent Library” are named in the original subscription book of the Italian Library Society. A number of these subscribers were also diligently studying Italian with Da Ponte. Shares were sold for five dollars, most subscribers buying one or two (Gulian C. Verplanck purchased five), and $340 was raised in this way. Several were bought by Columbia professors, among them Clement Moore, who had been a trustee of the New York Society Library since 1811. Lorenzo Da Ponte himself purchased a share, setting a good example and entitling him to such privileges of membership as checking out books.

The word “permanent” crops up several times in connection with these books, so it comes as a surprise that in April of 1830, Philip Jones Forbes, the librarian of the New York Society Library, reported that “Mr. Da Ponte has taken away all of the books he has deposited in the Library from time to time – excepting those sold to the Italian Library Society.” Almost sixty Italian authors were represented on the list of books that had been sold to the Italian Library Society at a total price slightly higher than the amount raised by subscription. These books were absorbed into the New York Society Library where they remain to this day.

The New York Society Library’s printed catalog of 1838 includes these along with fifty-five additional volumes of the Edizione di Classici Italiani, the gift of Messrs. Clement C. Moore, Gulian C. Verplanck, and John I. Morgan. Da Ponte favored these particular editions of Galileo, Cellini, Redi, and others, and it is likely that he persuaded his friends to purchase the series for the Society.

There are no special markings in the New York Society Library’s Italian books, but it can be assumed that most, if not all of the titles that also appear in the Catalogue of Printed Books. . .[for] L. Da Ponte’s Pupils and Subscribers, came from Da Ponte. As a subscriber to the Italian Library Society, he was authorized to check books out, and the subscription book, which includes circulation records, indicates that Da Ponte was the heaviest user of the Italian books.

On May 15, 1830, for example, he borrowed volumes two and three of Storia Fiorentina di Messer Benedetto Varchi (a five-volume set) but did not return them. After the books were long overdue, a librarian penciled next to the entry in the subscription book “still out.” The New York Society Library’s on-line catalog indicates that volumes two and three are lacking and presumably still checked out to the librettist.

At the same time that Da Ponte was overseeing the Italian Library Society, he was attending to his academic duties at Columbia College. The toothless and elderly professor must have seemed out of place among the other members of a faculty that consisted almost entirely of Columbia alumni. Fortunately, Da Ponte’s two closest friends in America were his colleagues, Clement Moore and his cousin Nathaniel Moore, the librarian who compiled the 1839 catalog of the Columbia College library and a future president of the college. The Professor of Italian had no fixed salary but was paid according to the number of students who enrolled in the elective course. Da Ponte attracted several students to the class in his first year at the college, but none signed up the second year.

In fact, after that first year, he never had another student, though he remained on the faculty for thirteen years. “Professor sine exemplo” (Professor without parallel) is the way Da Ponte characterized the mostly studentless years of his academic career.

When Professor Da Ponte arrived on campus in 1825, he discovered that the only Italian book in the library was a tattered Boccaccio. To remedy the deficiency – and to help with his recurring financial difficulties – early in 1826 he offered the library 263 Italian books for $364.05 and, on the recommendation of Clement Moore, 161 were purchased for $243.17½. During his years at Columbia, Da Ponte continued to import Italian books at a faster pace than he could sell them, though eventually he also numbered the Library of Congress and the Library Company of Philadelphia as his clients. In 1830 he opened his own bookshop: “My customers are few and far between,” he forlornly wrote in his Memoirs, “but I have, instead, the joy of seeing coaches and carriages drive up at every moment before my door and sometimes the most beautiful faces in the world emerge from them, mistaking my bookstore for the shop next door, where sweets and cakes are for sale.”

By 1831, the number of books on his shelves had swollen to 3000 volumes of “the most beautiful pages of our literature.” A financial crisis that year forced the luckless bookseller to put some 2000 of them in auction. “Alas, fate takes from me my only treasure!” he wrote as he said farewell to the books. “Death would have been less bitter than this last farewell.” He was almost ninety when he died in 1839.

According to the Columbia University website, the Italian department is still “Drawing on a distinguished history initiated in 1825 by Lorenzo Da Ponte.” It has a Lorenzo Da Ponte professorship and his portrait hangs at the university’s Italian Academy, formerly the Casa Italiana. The New York Society Library has a specially designated “Da Ponte Collection” that can be located on its on-line catalog through an author search. The 55 titles, comprising 247 volumes of the “the flower of our literature” are on the Special Collections shelves in the library. To this day, the two libraries are noted for their strong holdings in Italian literature.