In its multidirectional work, Centro Primo Levi finds continuous inspiration and guidance in the writings of scholars, artists, and thinkers from our times, and from the past. In facing the complexity of the present moment, we have been re-reading the luminous work of the art critic, essays, screenwriter, novelist, and painter John Berger (1926-2017). In 1972, his book Ways of Seeing and the homonymous TV series — an instant classic— inaugurated the field of cultural studies providing intellectual grounding for politically engaged artists and scholars.

His collection of essays, The Sense of Sight (Pantheon Books, 1985), is particularly relevant today as it shows how to pose questions to the visual world that allow us to respond, through insight and empathy, to the challenges ahead.

The essays’ topics range from the concept of self-portrait and the unsaid to the art of storytelling, musings on Manhattan and the city of Sodom, and the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. We are transported from the individual experiences of love and of loss, to some of the major political events of our time.

In The Sense of Sight, Berger breaks away from the perimeter of art history and encourages the reader toward a universalist view. Reading his reflections on art is, among other things, an invitation to share the author’s exceptional capacity for moral engagement.

On July 12, 2024, Amedeo Modigliani’s 140th birthday, we are delighted to announce that Verso will re-publish John Berger’s The Sense of Sight. This auspicious event allows us to celebrate and pay tribute to both Berger and Modigliani.

John Berger, Modigliani’s alphabet of love, 1981 (Courtesy Verso, London)

The photographs show a man who fits his own laconic description of himself: born in Livorno, Jew, painter. Sad, vital, furious and tender, a man never quite filling his own appearance, a man searching behind appearances. A man who painted unseeing eyes—often closed, and even when open without iris or pupils, and yet eyes which in their very absence speak. A man whose intimacy had always to traverse great distances. A man maybe like music, present and yet detached from the visible. And nevertheless a painter.

With van Gogh, Modigliani is probably one of the most regarded of modern artists. I mean that literally: the most looked-at by the most people. How many postcards of Modigliani at this moment on how many walls? He appeals particularly but not exclusively to the young. The young of succeeding generations.

This popular reputation has not been much encouraged by museums and art experts. In the art world during the last forty years Amedeo Modigliani, who died sixty years ago, has been acknowledged and, mostly, left aside. He may even be the only twentieth-century painter to have won, in this sense, an independent acknowledgment. Without cultural retailers. Beyond the reach of critics, Why should this be so?

In themselves his paintings demand little explanation. Indeed they impose a kind of silence, a listening. The whirrings of analysis become more usually pretentious. Yet the answer to the question has to be found within the paintings. A sociology of popular taste will not help much. Nor can much weight be given to the ‘Modigliani legend’. His life story, lending itself easily to film and sensational biographies, his apotheosis as the peintre maudit of Montparnasse in its heyday, the many women in his life, his poverty, his addiction, his early death, provoking the suicide of Jeanne Hebuterne, last companion, now buried near him in the cemetery of Père Lachaise: all this has become well known, but it has little to do with why his paintings speak to so many people.

And in this, Modigliani’s case is very different from van Gogh’s. The legend of van Gogh’s life enters the paintings, the two tumults mix. Whereas Modigliani’s paintings, instantly recognizable as they are, remain at a profound level anonymous. In face of them, it is not the trace or the struggle of a painter that we confront, but a completed image, its very completeness imposing a kind of listening, during which the painter slips away, and gradually through the image, the subject comes closer.

In the history of art there are portraits which announce the men and women portrayed —Holbein, Velasquez, Manet… there are others which call them back —Fra Angelico, Goya, Modigliani, among others. The special appeal of Modigliani is surely related to his method as a painter. Not his technical procedure as such, but the method by which his vision transformed the visible. All painting, even hyper-realism, transforms.

Only by considering a painting’s method, the practice of its transformation, can we be confident about the direction of its image, the direction of the image’s passage toward us and past us. Every painting comes from far away (many fail to reach us), yet we only receive a painting fully if we are looking in the direction from which it has come. This is why seeing a painting is so different from seeing an object.

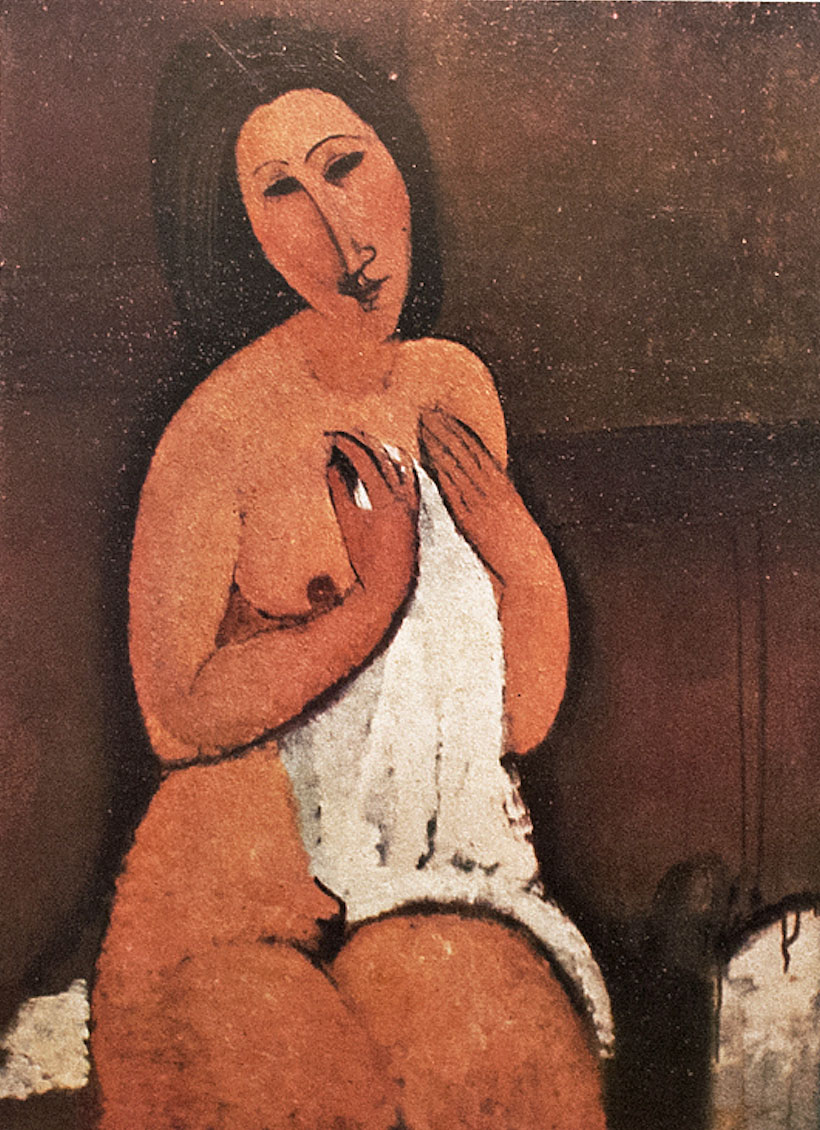

A single drawn curve on a flat surface —not a straight line— is already playing with the special power of drawn imagery. The curve stays on the surface like that of the letter C when written, and, at the same time, it can leave the surface and be filled out by an approaching volume which may be a pebble, an orange, a shoulder.

Modigliani began each painting with curves. The curve of an eyebrow, the shoulders, a head, a hip, a knee, the knuckles. And after hours of work, correction, refinement, searching, he hoped to re-find, preserve, the double function of the curve. He hoped to find curves that simultaneously would be both letter and flesh, would constitute something like a person’s name to those who know the person. The name which is both word and physical presence.

ANTONIA

At the time of Cubism and its collages, it was not unusual for painters to introduce written words or even single letters into their paintings. And therefore one should not attach too much importance to Modigliani doing the same. And yet when he did so, the letters always spelt out the name of the sitter: they did in their way what the paint was doing in its way—both recalling the person.

More profound and important, however, is that where there are no words, the curves in Modigliani’s paintings, the curves with which he began, are still both two-dimensional like print, and three-dimensional like the line of a cheek or breast. It is this which gives to almost every figure painted by Modigliani something of the quality of a silhouette—although in fact these figures glow, and are, in other ways, the opposite of silhouettes. But a silhouette is both substance and two-dimensional sign. A silhouette is both writing and existence.

Let us now consider the long, often violent process by which he proceeded from the initial curves to the finished vibrant static image. What did he intuitively seek through this process? He sought an invented letter, a monogram, a shape, which would print as permanent the transient living form he was looking at.

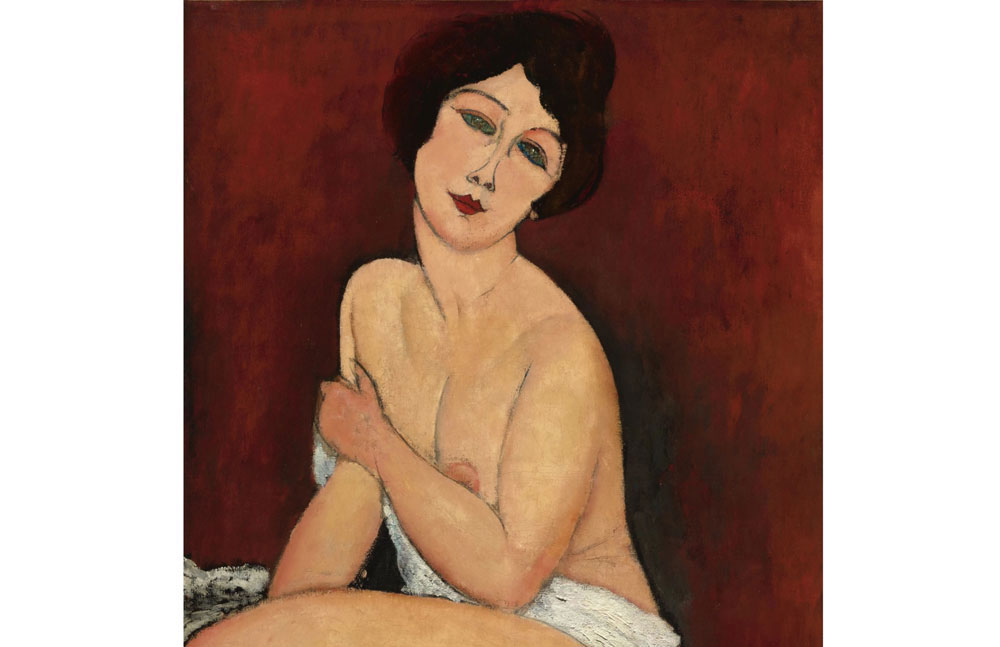

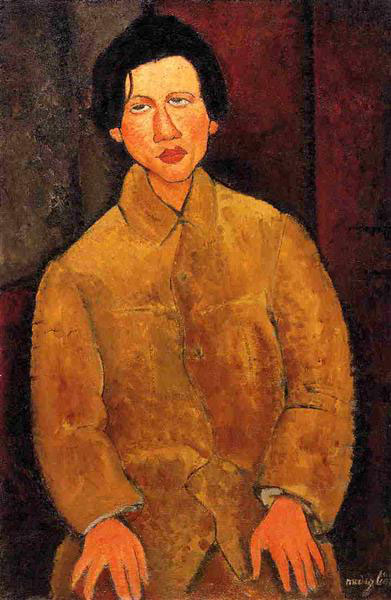

The achieving of such a shape was the result of numerous corrections and redrawn simplifications. Unlike many artists, Modigliani began with a simplification and drawing was the process of letting the living form complicate it. In his masterpieces like ‘Nu Assis à la Chemise’ 81917), ‘Elvira Assise’ (1918), ‘La Belle Romaine’ (1917) or ‘Chaim Soutine’ (1916), the dialectic between simplification and complexity becomes hypnotic: what our eyes see swings like a pendulum, ceaselessly between the two.

And it is here that we find Modigliani’s remarkable visual originality. He discovered new simplifications. Or, to put it, I think, more accurately, he allowed the model, in that life and in that pose, to offer him new simplifications. When this happened, a shape, that part of the simplified invented letter, which meant an arm resting on the table, an elbow resting on a hip, a pair of legs crossed, this shape, cut for the first and unique time during the drawing of those sessions, turned like a key in its lock, and a door swung open open on the very life of the limbs in question.An invented letter, a monogram, a name, the profile of a key —each of these comparisons stresses the stamped emblematic quality of the drawing in Modigliani’s paintings. But what of their colour? His colours are as instantly recognizable as his use of line and curves. And as amazing. Nobody for the last two centuries panted flesh as radiantly as he did. And then, if in one’s mind one compares him with Titian or Rubens, what is specific to his use of colour becomes clearer. It is complimentary to what we have already seen about his drawing.

His colour is sensuously, mysteriously (how did he achieve that glow and bloom?) articulated to the present, to the tangible and to what extends in space, and it is also emblematic. The radiance of the body becomes an emblematic field of intimacy. It is at one and the same time body, and the aura of that body as lovingly perceived by another. I put it like that because the other is not necessarily or exclusively a lover in the sexual sense. The bodies painted by Modigliani are more transcendent than those painted by Titian or Rubens. They have perhaps a certain affinity with some figures by Botticelli, but Botticelli’s art was social, its symbolism and myths were public, whereas Modigliani’s are solitary and private.

When critics discuss the influences behind Modigliani’s art (he was thirty and had seven more years to live when he achieved true independence), they speak of the Italian primitives, Byzantine art, Ingres, Toulouse-Lautrec, Cézanne, Brancusi, African sculpture. The latter had a very direct influence on on his carving which, in my opinion, is unremarkable when compared to his painting. His sculpture remains a casing: the spirit of the subjects is never freed. Non of the visual dialectic we have examined can easily be apply to sculpture.

Yet it has always seemed to me that if Modigliani’s art has a close affinity with another, it is with the art of the Russian icon—although here there was probably no direct influence. The profound affinity is not stylistic. There may sometimes be a superficial resemblance in the ‘silhouettes’ of the figures, but in general the icon figures are more fluid, less taut; their grace was a given, and did not have to be rescued anew each time. The resemblance lies in the quality of the presence of the figures.

They are attendant. They have been called back, and they wait. They wait with such patience, such calm, that one can almost say that they wait with abandon, and what they have abandoned is time. They are still like a coastline is still before the endless movement of the sea. They are there for when all has been said and done. And this distance—which is not a question of superiority but of span, in the sense of a roof spanning what happens in a house —means that in their presence there is a quality of absence. All this is at a first degree. At the second, as soon as they enter the mind of the spectator—and it is this which they are awaiting—they become more present than the immediate.

Obviously this affinity cannot be pushed too far. On one hand, there are religious images of a traditional faith; on the other, secular images wrenched from a lonely and tempestuous modern live. Yet Modigliani’s admiration for the mystical poetry of Max Jacob, much of his reading, and the titles he gave to some of his paintings, are a reminder that he at least might not have found the comparison surprising.

Let me now resume what we have so far noticed, before attempting an answer to the question with which I began. Modigliani wanted his paintings to name his subjects. He wanted them to have the constancy of a sign—like a monogram or an initial—and, equally, he wanted them to possess the variability, the temperamentality, the sentience of the flesh. He wanted his paintings to summon up the presence of the sitter and to diffuse it, but diffuse it as an aura within his and the spectators’s imagination or memory.

He wanted his paintings to address both the flesh and the soul. And in his best works—through his method as a painter, not through simple nostalgia o yearning—this is what he achieved.

His paintings are so widely acknowledged because they speak of love. Often explicitly sexual, sometimes not. Many painters have painted images of lovers, others—like Picasso—have painted images polarized by their own desire, but Modigliani painted images such as love invents to picture a loved one. (When no tenderness existed between him and his model, he failed and produced mere exercises.)

That he was usually able to achieve this without sentimentality was the consequence of his extraordinary rigour. He knew that the problem was to find and reveal the structural laws, the gestalt, of some of the ways by which love visualizes a loved one. He was concerned with romantic love, seduction; his images are about being in love. They are distinct from, for example, Rembrandt’s images of love as familiarity and communion.

Nevertheless, despite his romanticism, Modigliani refused the obvious romantic short cuts of symbols, gestures, smiles or expressions. This is probably the reason why he often suppressed the look of the eyes. He was, at his strongest, not interested in the obvious signs of reciprocal love. But only in how love holds and transports its own image of a loved one. How the image concentrates, diffuses, distinguishes, and is both emblem and existence like a name.

Antonia.

Everything begins with the skin, the flesh, the surface of that body, the envelope of that soul. Whether the body is naked or clothed, whether the extent of that skin is finally bordered by a fringe of hair, by a neckline of a dress, or by a contour of a torso or a flank, makes little difference. Whether the body is male or female makes no difference. All that makes a difference is whether the painter had, or had not, crossed the frontier of imaginary intimacy on the far side of which a vertiginous tenderness begins. Everything begins with the skin and what outlines it. And everything is completed there too. Along that outline are assembled the stakes of Modigliani’s art.

And what is at stake? The ancient—and how ancient!—meeting between the finite and the infinite. The meeting, the recurring rendezvous, only takes place, so far as we know, within the human mind and heart. And it is both very complex and very simple. A loved one is finite. The feeling provoked are felt as infinite. Against the law of entropy, there is only the faith of love. But if this were all, there would be no outline, only a blending, a merging of the two.

A loved one is also singular, distinct, separate. The more closely one defines, regardless of any given values, the more intimately one loves. The finite outline is a proof of its opposite, the infinity of emotion provoked by what that outline contains. This is the deepest reason for the frequent elongation of Modigliani’s figures and faces. The elongation is the result of the closest possible definition, of wanting to be closer.

And the infinite? the infinite in Modigliani’s painting, as in the icons, abandons space and enters the realm of time in order to try to overcome it. The infinite seeks a sign, an emblem: it attaches itself to a name which belongs to a language that, unlike the body, endures.

ANTONIA.

I would nor suggest that the entire secret of Modigliani’s art or of what his paintings say is identical to the secret of being in love. But the two do have something in common. And it may be this which has escaped the art theorists, but not those who pin up in their rooms postcards of Amedeo Modigliani’s paintings.