The Enigma of a Rare Jewish Sixteenth Century Portrait from Cremona

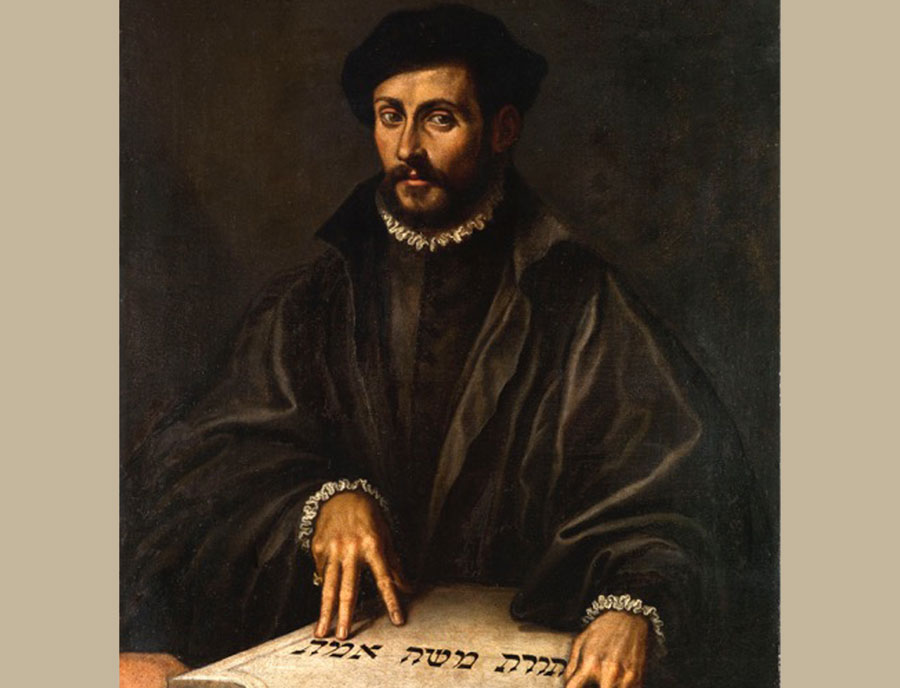

Recently, while visiting an art fair in New York, I was surprised and intrigued by a painting by Antonio Campi (Cremona 1524 -1587) prominently hanging at Robert Simon Fine Art’s booth. Titled Portrait of a Man Pointing at a Hebrew Tablet, and depicting a young well-dressed Jewish man in a moment of contemplation, it is a rare portrait of a Jew in secular Italian Renaissance art.

Who is the sitter? And what can a painting like this tell us about the Jews in Sixteenth Century Cremona? Could his defiant expression and the inscription on the tablet hint to the threats of expulsion from Cremona, which loomed as early as 1552?

If one were to characterize in broad brushstrokes the experience of the Jews living in Italy during the Renaissance, one would have to place them in the larger context of the general population, within a period marked by cultural flourishing, economic advancement and the beginnings of modern science.

In the era of the birth of the ghetto and Papal anti-Judaic legislation, historians record a kind of conditional tolerance of Italian communes and princedoms toward the Jewish population. Tolerance in the sense of granting Jews the privilege to live among Christians, provided they serve a beneficial role to society as a whole and proved not to pose a threat to Christianity.

The Jews that had resided continuously since ancient Roman times in the various states, large and small, that made up the Italian Peninsula, had been joined by a significant influx of Jews arriving from all over Europe. While much of Western Europe had seen a decline in Jewish population following the expulsions from England in 1290, from France between 1182 and 1394, and most significantly from Spain in 1492 and Portugal in 1497, Italy was a place of demographic expansion for the Jews. The socio-economic achievements of the Jews in Italy during this period were aided by the ecclesiastical approval of Jewish moneylending.

Aside from moneylending, Jews were active mostly as doctors, teachers, and book printers. A majority of Italian rulers and noblemen employed Jewish physicians, who influenced them in more than just medical matters; a growing number of Christian scholars studied Hebrew and employed Jewish teachers in what is called the School of Christian Hebraists. Jews were also very active in typography as Italy became the bedrock of Jewish book production worldwide.

And yet… representations of Jews and Jewish life in Renaissance Italian painting (aside from biblical themes) tell a very different story. In her The Jews In Art of the Italian Renaissance, (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008) Dana E. Katz proposes an interesting hypothesis. She suggests that Italian Renaissance painting became part of a policy of tolerance that deflected violence from the real world onto a symbolic world. While the rulers upheld tolerance toward the Jews, they simultaneously supported artistic commissions that perpetuated violence against them. “Before the calm night sky and peaceful rolling hills of a northern Italian landscape, a Jewish moneylender, his wife, and two young children are burned at the stake in Paolo Uccello’s 1468 predella panel for the Corpus Domini Altarpiece in Urbino. Renaissance paintings in other northern Italian cities resemble Uccello’s panel in that they portray Jews as deviant outcasts of Italian society. In Mantua’s Santa Maria della Vittoria, a Madonna and Child altarpiece depicts the Jewish moneylender Daniele da Norsa who allegedly desecrated a Christian image. […] Placed within ecclesiastical and monastic spaces for Christian consumption, these paintings are images of punishment, commissioned or approved by the despotic rulers of Italy to humiliate and deprecate Jews.”

With Katz’s compelling argument in mind, I ventured to imagine Antonio Campi’s painting in the context of Jewish–Christian relations in Sixteen Century Cremona.

The city of Cremona, in Lombardy, had a flourishing Jewish community starting from the end of the Fourteenth Century up to its forced expulsion of 1597. Could the painting foreshadow the grave perils awaiting the Jews of Cremona?

The Duchy of Milan, to which Cremona belonged, had been ruled by the Visconti family up to 1447.It was subsequently ruled by the Sforza’s until 1535 when Charles V of Spain took its possession. From then, for one hundred and eight years, the history of Cremona followed that of Spanish rule in Italy¹.

Despite an influx of German Jews, Milan had never formally granted residence to the Jews, making Cremona the point of reference for most Jews in the Duchy. The Jews of Cremona – bankers, doctors, merchants and typographers – lived in a Giudecca that extended between what are today Via Cavallotti, Via Grandi and Via Gramsci, with the Synagogue on Via Capitani del Popolo. Both Cremona and the nearby town of Soncino (where the first printing press in Italy with Hebrew characters was assembled) were renowned centers of Jewish printing and bookbinding.

Roberto Bonfil² suggests that following the abrupt standstill of Jewish book making in Venice in 1553, (due to the Papal bull ordering the burning of the Talmud), for a brief period, from 1553 to 1560, Cremona took Venice’s place as the European center of Jewish publishing.

Interestingly, the most renowned printer of Hebrew books in Cremona was a gentile, Vincenzo Conti, who had been employed until 1553 by Jewish printers in Venice. He also collaborated with Francesco Marcolini, the printer of the Accademia dei Pellegrini. In 1554 Conti asked the Jewish community of Cremona for employment, which he obtained as stated in the foreword of Provisiones Navigii. In 1556 he collaborated to the publication of an editio princeps of Jacob Levita’s Sefer minhagim in Sabbioneta. Persecuted by the Inquisition for the many Hebrew books he had printed, Conti eventually left Cremona for Riva di Trento where he continued to print Hebrew books.

The Jews of Cremona were also known for wood harvesting. The Jewish family Bachi supplied wood from Val Seriana to Gasparo (Bertolotti )da Salò (1542-1690), a virtuoso player and one of the first makers of the modern violin³.

Relations between the Jews and the Christian majority are long described as peaceful, with occasional tension rising over financial issues. In order to compete with Jewish moneylenders, a Christian Monte di Pietà (pawnshop) was established around 1500. But with the advent of Counter-Reformation, the Franciscans and several minor orders fomented anti-Jewish sentiments.

By 1525 Cremonese Jews were forced to wear a yellow cap as an identification sign, while the counter-Reformation zealots were actively spreading hatred towards “heretici et hebrei”. In 1588 the Jewish community of Cremona numbered 456 persons and was well organized. The reputation of the community extended beyond its borders. The community was always ready to render aid to the persecuted, as in the case of the Marranos of Pesaro4.

Following Pope Julius III bull ordering the burning of Hebrew books, in Cremona also such books were confiscated, brought to the convent of San Domenico and destroyed (only a small percentage escaped the flames, such as a precious Hebrew Bible published in 1546, today in Cremona’s public library).

The Spaniards have often been considered responsible for the expulsion of the Jews from the Duchy Of Milan. In reality, emperor Charles V of Spain had assigned the Duchy of Milan to his son Philip II as early as 1540, and Jews had continued to reside in the Duchy, including in Cremona, for quite some time after. The Spanish court was eventually urged by the Church – specifically by the Archbishop of Milan, Carlo Borromeo, and the Bishop of Cremona, Niccolò Sfrondati, (later Pope Gregorio XVI)—to proceed with the final expulsion of the Jews, which occurred in 1597.

Robert Simon is an expert in Old Master paintings, connoisseurship, and collecting. He has been a research fellow at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well as a consultant to museums, art dealers, institutions, and private collectors.’

He shared some of his research and insights on the stunning Portrait of a Man Pointing at a Hebrew Tablet.

AC What can you tell us about the iconography and significance of this most unusual painting?

RS While its full significance is yet to be understood, it is a remarkable and unexpected vestige of Jewish culture and life in Sixteenth Century Italy. This Portrait of a Man is striking not only for its considerable pictorial quality, but also for its rare iconography. The subject is a bearded man of about thirty, elegantly, if severely dressed in a black doublet, over which he wears a high-collared black cloak. His dress is complemented by a matching berretto as he sits before a table on which rests a stone tablet, carved on top with volute borders, and inscribed with Hebrew lettering. While Hebrew inscriptions, usually diminutively placed, may appear in Italian Fifteenth and Sixteenth century religious paintings, the prominent presence of one in a secular portrait is unusual, if not unique.

AC Let us focus on the inscription…

RS The content of the inscription itself makes the portrait all the more extraordinary. The elegantly rendered Hebrew letters —inverted so that the viewer can read them— state Torat Moshe Emet or The Torah (or Law) of Moses is the Truth”. Such a bold statement can only have had great personal significance to the sitter and there can be little doubt that he was a member of one of the Jewish Communities in Northern Italy, most likely Cremona, the artist’s home for most of his life. The presence of a diamond ring suggests the sitter’s profession, perhaps a goldsmith, his name, or simply an attribute of his distinction or wealth.

AC Are you aware of any further interpretations?

RS It has been remarked that the subject of the portrait rests his right hand near the last word of the inscription, with two elegant fingers placed above the last two letters of the word Emet (Truth). Those two characters— Mem and Tav— together form the word Met, (Death). It is difficult to know whether this arrangement of the hand has any import other than aesthetic. But if there is some kind of coded meaning, it might suggest that the present work is a commemorative portrait of one who has died young, an idea underscored by the memorializing associations of a stone tablet. Militating against such a hypothesis is the enlivened manner of the subject, who engages with the viewer with an almost questioning expression.

AC Do we know much about the artist?

RS The painting, which is not signed, has been convincingly attributed to the Cremonese artist Antonio Campi on stylistic grounds. Campi trained under his older brother Giulio, with whom he shared a studio and collaborated on several projects before the two formally ended their partnership in 1560 and commenced independent careers. That year Antonio was documented in Milan, painting a Resurrection for the Church of Santa Maria presso San Celso, which remains in the church. In the following years he worked on various commissions both in Milano and Cremona, including several for the powerful Archbishop of Milano, St. Carlo Borromeo. He undertook a variety of ecclesiastical and domestic projects throughout Northern Italy, in Lodi, Meda, Milan, Piacenza and Crema. However, the focus of his activity remained Milan and his native Cremona, where he died in 1587. As well as being a painter, Antonio was known as an architect, sculptor, and writer. His history of his city, Cremona fedelissima città, was published in 1582 and included portraits, maps and biographies of notable figures. Of great interest to us are the large foldout maps of Cremona that appear on page 81 and 130-1. Drawn by Antonio, they were engraved by David de Laude (David da Lodi) and present the earliest known prints made by a Jewish engraver in Italy. Proudly signed “David de Laude Hebreus Cremonensis”, this collaboration attests to the artistic cooperation and tolerance that existed in Cremona at that time.

Footnotes

1. Cremona,” ITALIA JUDAICA, accessed 10 luglio 2016, http://www7.tau.ac.il/omeka/italjuda/items/show/865.

2. Gli Ebrei a Cremona, Giovanni Magnoli ed., Florence, La Giuntina, 2002.

3. Carlo Bonetti Gli ebrei a Cremona 1278-1630 (Cremona 1917; repr. Bologna 1982.)

4. http://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/4750-cremona

Further readings

www.academia.edu/16209640/Appunti_per_una_storia_degli_ebrei_a_Cremona

Marina Caffiero Storia Degli ebrei nell’Italia moderna, carucci Editore, Roma 2014

Robert Bonfil, Jewish LIfe in Renaissance Italy, translated by Anthony Oldcorn.

Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994

Renata Segre, Gli ebrei lombardi nell’età spagnola: storia di un’espulsione, Torino: Accademia delle scienze, 1973

E. Horowitz, I Carmi di Cremona: una famiglia di banchieri ashkenaziti nella prima età moderna, in «Zakhor», III (1999), pp. 155-170

Franco Bontempi, Storia della comunità ebraica a Cremona e nella sua provincia, Brescia: Società per la storia del popolo ebraico, 2002

Michele Luzzati, Banchi e insediamenti ebraici nell’Italia centro settentrionale fra tardo medioevo e inizi dell’età moderna, in Storia d’Italia Einaudi, Torino: Einaudi, 1996, vol. 11/1, pp. 175-238