Stanislao G. Pugliese is professor of modern European history and the Queensboro Unico Distinguished Professor of Italian and Italian American Studies at Hofstra University.

He is a former research fellow at the Italian Academy for Advanced Studies at Columbia University, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., the University of Oxford, Harvard University, the Center for European and Mediterranean Studies, at NYU and the inaugural Italian Scientists and Scholars of North America Foundation fellow at the Istituto Campano per la Storia della Resistenza in Naples. In 2020, he will be a Fulbright Scholar at the Università della Calabria in Italy teaching a graduate-level course in Italian American Culture and Literature.

A specialist on modern Italy, the anti-fascist Resistance and Italian Jews, Dr. Pugliese is the author, editor or translator of fifteen books on Italian and Italian American history. In 2009, Farrar, Straus and Giroux published Bitter Spring: A Life of Ignazio Silone which won the Fraenkel Prize in London, the Premio Flaiano in Italy and the Howard Marraro Prize from the American Historical Association. The book was also nominated for a National Book Critics Circle award. His Op-Ed essay, “Earthquake at the Door,” appeared in the New York Times on April 6, 2009.

His first book, Carlo Rosselli: Socialist Heretic and Antifascist Exile (Harvard University Press, 1999) has been translated into Italian, Russian and Romanian. His essays on Italian and Italian-American history and culture regularly appear in academic and popular journals, and he is the editor of the Italian and Italian American Studies series published by Palgrave Macmillan. He has organized several international conferences and has edited numerous volumes of conference proceedings including The Most Ancient of Minorities: The Jews of Italy; The Political Legacy of Margaret Thatcher; Frank Sinatra: History, Identity and Italian-American Culture; as well as The Legacy of Primo Levi and Answering Auschwitz: Primo Levi’s Science and Humanism After the Fall. Other books are Desperate Inscriptions: Graffiti from the Nazi Prison in Rome, 1943-1944 and an anthology, Fascism, Anti-Fascism and the Resistance in Italy. He edited a new English edition of Carlo Levi’s Fear of Freedom and the first English translation of Claudio Pavone’s landmark work A Civil War: A History of the Italian Resistance. With Brenda Elsey, he is co-editor of Football and the Boundaries of History: Critical Studies in Soccer; with William J. Connell he is co-editor of The Routledge History of Italian Americans (Italian translation by Mondadori); with Pellegrino D’Acierno he is co-editor of Delirious Naples: A Cultural History of the City of the Sun.

Professor Pugliese began teaching full time at Hofstra in 1994. His essay, “The Books of the Roman Ghetto Under the Nazi Occupation” was presented as the 17th Annual Distinguished Faculty Lecture in 1999, was awarded the Peter E. Herman Literary Award at Hofstra University, and has been translated into Italian. Since 1996, he has directed the Italian American Lecture Series at Hofstra University. The Association of Italian American Educators named him College Professor of the Year for 2005. In 2009 he was named a Fellow of the Hofstra Cultural Center.

The recipient of numerous awards and honors, Dr. Pugliese is a member of the National Book Critics Circle and his reviews have appeared in The New York Times Book Review, The Philadelphia Inquirer, and The American Historical Review among many other publications. He has been interviewed on National Public Radio as well as Voice of America.

Professor Pugliese has presented his work at Harvard, Yale, Columbia, Cornell, Bard College, Yeshiva University, Williams, the University of Michigan, West Point, Syracuse University, the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington, D.C., as well as overseas in London, Paris, Moscow, Rome, Florence, Taormina, Bari, Naples, Toronto, Utrecht, and Jerusalem. He is currently working on a new book tentatively titled Dancing on a Volcano in Naples: Scenes from the Siren City

Edited for Printed Matter. Original version with notes published in Allegoria.

Every age has its fascism. Primo Levi

When Fear of Freedom was first published in Italy in 1946, critics were puzzled: was this the same Carlo Levi whose extraordinary Christ Stopped in Eboli had appeared the previous year? With its concrete imagery and compassionate ethnography, that earlier book had won over not only the Italian literary establishment and its various political currents, but the larger public as well. Fear of Freedom seemed to have been written by an entirely different author. And yet, there is a clear genealogy between the two; indeed, the later essay must be recognized as the interpretive key to understanding Levi’s entire oeuvre. It was not until the second edition was published in 1964, that Italo Calvino understood, before other critics, that «Levi […] is witness of the presence of another time within our time, the ambassador of another world to ours».

Paura della libertà is a work that is sui generis. Levi called it «a philosophical poem» and meant it to serve as an introduction to a larger work, perhaps a grand master narrative. In some ways, his elegiac post-war novel The Watch (1950) took up this meditation on time, memory, and history in a different, more intimate, form.

Written as war clouds were gathering over Europe, Fear of Freedom is a lyrical and metaphysical thinking-through of man’s flight from moral and spiritual autonomy and the resulting loss of self and creativity. As he watched British troops disembark in the fall of 1939 on the western coast of France, Levi brooded on what surely appeared to be the decline, if not the fall, of Europe as the German armies prepared to eviscerate an entire world.

Levi approaches the problem of fascism through poetic language, employing a lexicon of metaphor, symbolism, poetry and mythology. Without access to a library but with references to the entire intellectual and cultural patrimony of Western civilization (from the Bible and Greek mythology to Freud and Jung; from the eighteenth-century counter-Enlightenment Neapolitan philosopher Giambattista Vico to Friedrich Nietzsche), Levi’s book is a profound mythopoetic meditation on the paradoxical relationship between human beings, freedom, and the creative process. Fear of Freedom is not only a meditation on a specific moment in history and a universal, timeless condition.

Carlo Levi earned a degree in medicine from the University of Turin in 1924 though he never officially practiced medicine. Instead, he gravitated toward painting and – in the context of the fascist dictatorship of Benito Mussolini – anti-fascist politics. The two activities – painting and anti-fascism – were intimately connected in his mind. Anti-fascism required a new style of painting, one capable of freeing men and women from fear. Conversely, Levi saw in certain forms of contemporary painting – especially the tendency away from figurative art and the human form – a reflection of an eternal tendency to flee from freedom.

Levi embraced Piero Gobetti’s thesis that Italy, never having fully experienced the great transformative events of modernity such as the religious, political, scientific and intellectual revolutions of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, had never really reached political “maturity.” It was through Gobetti that Levi came to know a Sardinian intellectual transplanted into the soil of Turin: Antonio Gramsci, a founding member of the Partito Comunista Italiano (PCI). Levi embraced Gobetti’s condemnation that fascism was no mere parenthesis in Italian history, as Benedetto Croce would interpret the fascist ventennio in an influential 1944 speech, nor an aberration of Italian history, but «the autobiography of a nation»; a nation that rejected the necessary compromise of politics; a nation that worshiped unanimity; a nation that feared heresy.

In addition to his relationships with Gobetti and Gramsci, another crucial friendship was that with Carlo and Nello Rosselli. Carlo, the elder brother, was a co-founder of a new political movement Giustizia e Libertà, and one of the most charismatic and influential of European anti-fascist intellectuals. Born into a Jewish family and abandoning a promising career as a professor of political economics, Rosselli devoted his considerable family fortune and ultimately his life to the struggle against fascism. In 1925, he was instrumental in establishing the first underground antifascist newspaper, «Non Mollare!».

Rosselli had been sentenced, as would Levi later, to confino or domestic exile, on Lipari. There, he wrote his major theoretical work, Socialismo Liberale, arguing that socialism was the logical development of the principle of liberty. After a daring escape from the island of Lipari, he made his way to Paris. With his historian brother Nello and Riccardo Bauer, Carlo Levi founded a new journal in Turin, «La lotta politica», in 1929. If Carlo Levi and Nello Rosselli represented an intellectual resistance against fascism, Carlo Rosselli was the epitome of the anti-fascist activist. He was among the first to arrive in Barcelona after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, in which he commanded an armed column of volunteers in defense of the Republic. When the secret police learned of Rosselli’s plan to expand the Spanish Civil War into a pre-emptive strike against Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany and discovered his plot to assassinate Mussolini, they declared him the regime’s most dangerous enemy and had him murdered, along with his brother Nello, on a country road in Normandy. Levi, intellectually and emotionally close to both brothers, worked through his grief by painting a revealing Autoritratto con la camicia insanguinata.

Levi was strongly attracted to the radical new ideology of Giustizia e Libertà. The movement stressed that, unlike the other anti-fascist parties such as the Partito Socialista Italiano (PSI) and the PCI which had their roots in a pre-fascist Italy, GL was the only movement that arose directly in response to Mussolini’s regime. It was a heterogeneous group of intellectuals; both a strength and a weakness. Levi was, together with Leone Ginzburg, Vittorio Foa, Augusto Monti, Aldo Garosci, Piero Gobetti’s extraordinary widow, Ada, and others, one of the leaders of GL in Turin.

It was because of Levi’s experience in confino in Basilicata that these northern Italian intellectuals were forced to confront the seemingly-intractable problem of meridionalismo or «la questione del Mezzogiorno», which had first been broached by Guido Dorso, Gaetano Salvemini, and Giustino Fortunato. When GL was accused of vague ideas, inarticulate anti-fascism and «povertà intellettuale» by Giorgio Amendola and the PCI, Levi worked with Carlo Rosselli, Emilio Lussu, Alberto Tarchiani and others in drafting the Programma rivoluzionario di «Giustizia e Libertà».

Fascism could only be defeated by a revolutionary movement that confronted the problem of freedom. They argued that GL was «the tangible expression» of the forces that struggle on the revolutionary terrain against fascism. Its program: abolish the monarchy; foster forms of democracy and autonomy based on the working classes; land reform; nationalization of essential public services; better industrial relations, factory organization, and workers’ control (reflecting the influence of Gobetti and Gramsci); unemployment insurance and a minimum wage; a foreign policy of peace and disarmament with greatly reduced military and colonial spending; freedom for the inhabitants of the colonies; a united Europe; cultural and administrative autonomy for ethnic minorities; free education; separation of Church and State; and unconditional freedom of conscience and worship. In short, for GL, the liberal, monarchical, past was no model for an anti-fascist and post-fascist Italy. Levi argued that pre-fascist Italy was directly responsible for the politically monstrous birth of fascism. There could be no nostalgic «ritorno al passato».

GL soon became known as the “il partito degli intellettuali”; in fact, its great flaw was its difficulty in attracting factory workers, artisans, the bourgeoisie or peasants. More ominously, in the reports of the fascist secret police, GL was soon labeled «il partito degli intellettuali ebrei». When Sion Segre Amar, a young idealistic man from Turin approached Carlo Levi about joining the movement, Levi could only moan, «Ahimè, un altro ebreo». Levi made it clear to the young man that he didn’t want GL to be known as a “Jewish” movement. Segre wittily asked if he should first convert to Catholicism to join, or should he become a fascist just because he was a Jew? Amar was clear on why Italian Jews were attracted to GL: fascism offended them morally, and they saw in the movement a vehicle to combat the odious ideology without constricting them in an equally rigid ideology such as communism.

The Turin branch of GL was deeply immersed in the cultural battle raging within Italy during the 1930s. Levi’s practice of painting portraits in his studio in Turin offered ample time and sufficient cover to discuss anti-fascism with others. Under the patronage of Giulio Einaudi and the Einaudi publishing house, Carlo Levi, Leone Ginzburg, Cesare Pavese, and Luigi Salvatorelli came together to revive the journal «La Cultura». Levi there signed his work with the nome de plume «Tre Stelle».

In the spring of 1935, the Turinese GL group was betrayed by a police spy and most of its members arrested by the fascists. Levi was interrogated and then sent to Rome’s notorious Regina Coeli prison. Two months after his arrest he was sentenced to three years of confino in Basilicata, first in Grassano, then Aliano. During his confinement, he was permitted to receive visitors, the most important being his sister Luisa and his lover, Paola Levi, who was Adriano Olivetti’s wife, and whose portrait he painted several times.

It was out of that year in confino that, eight years later, hiding from the Nazis in Florence, he was to write his most famous work, a masterpiece of ethnography and human solidarity, Cristo si è fermato a Eboli. For a northern Italian – and a Jew – the experience of the lives of the southern Italian peasant came as a revelation. Levi soon came to recognize that beneath a thin veneer of Christianity lay millennia of pagan culture.

On May 20, 1936, in celebration of the fascist acquisition of an “African Empire” after the defeat of Ethiopia, Levi and other political prisoners were granted an amnesty and released. Levi, though, did not immediately leave. The year he had spent in Aliano had marked him for life; in accordance with his last wishes, he is buried there.

Levi, Carlo Rosselli, and other members of GL, developed a conception of fascism that would be echoed several decades later in the work of the German-born psychoanalyst and social philosopher, Erich Fromm.

Levi saw the deep roots of fascism in the «inherited inability to be free» and in the «the fear of passion and responsibility that leads to worship who free us from them». The Italians, for Levi feel «the need of an exterior order that can be held as evidence or even substituted to the nonexistent morality». Emilio Lussu, for his part, agreed with Gobetti, Rosselli, and Levi that the Italians had inherited a moral conscience brutalized by centuries of feudalism and Catholicism.

Levi and his colleagues were anticipating Italian Liberal philosopher Benedetto Croce’s later formulation of fascism as «moral sickness» with roots in rabid nationalism, fanatical imperialism, romantic decadentism, and the First World War. By defining fascism first as a «parenthesis» in the unfolding history of liberty in Italy and then later as a «moral sickness», Croce was crafting a strategy that could deny that there was anything specifically “Italian” about fascism.

Levi, Rosselli, and Ferruccio Parri instead condemned the entire experience of Liberal Italy, from unification to the Great War, as responsible for the rise of fascism. Levi agreed with Parri’s condemnation that «tra lo stato italiano dopo il 1860 e il fascismo esiste una connessione; se non di affiliazione, di degenerazione progressiva».

For Levi, there were other forces as well that contributed to the rise of fascism: hundreds of thousands of people who supported the mechanism of the bureaucratic and dictatorial State; the cult of violence, a taste for adventure, and authoritarian tendencies generated by the war; a religion of nationalism; weakness of character in the part of the Italians; centuries of servility; the influence of the Church; and political apathy. In short, fascism was both class reaction and moral crisis, and those that fought only the former were fighting only half the battle.

Levi’s analysis of future forms of political organization can be seen in the contemporary version of a “media regime”:

We cannot foresee the political forms of the future, but in a bourgeois country like Italy, where bourgeois ideology has infected the masses of workers in the city, it is probable, alas, that the new institutions arising after Fascism, through either gradual evolution or violence, no matter how extreme and revolutionary they may be in appearance, will maintain the same ideology under different forms and create a new State equally far removed from real life, equally idolatrous and abstract, a perpetuation under new slogans and new flags of the worst features of the eternal tendency toward Fascism.

Levi’s warning about an «eterno fascismo» seems ever more prescient.

According to Levi, the only response to fascism lay in inventing a new form of government, a new conception of the State «that can no longer be fascist, liberal, nor communist—forms that are at the simultaneously different and identical to the same religion of the state». Instead, it was imperative that Italy reconceptualize the idea of the State with that of the individual. Levi thought he discerned the answer in peasant civilization. The humanistic yet tragic conception of the individual which was at the heart of peasant culture was the only path he saw to exit the vicious perpetuation of fascism.

That other extraordinary Levi from Turin – Primo Levi – had also discerned fascism’s eternal fascination. Writing during the “anni di piombo” Primo Levi courageously wrote in the Corriere della Sera in 1974:

Every age has its fascism: the premonitory signs can be seen wherever the concentration of power denies citizens the possibility and the ability to express themselves and implement their will. This is achieved in many ways, not necessarily by the terror of police intimidation, but also by denying or distorting information, polluting justice, paralyzing schools, spreading in many subtle ways nostalgia for a world in which order reigned supreme, and in which the security of the privileged few rested on forced labor and the silence of the many.

Intimately tied to two cities – his native Turin and his adopted Rome – Carlo Levi uncannily saw the modern metropolis as a metaphor for the dark indistinctness of chaos. Just as the free individual and the creative artist had to break free yet retain ties to the primeval mass, the contemporary city dweller had to navigate the labyrinth crafted by modern technology. Just as the ancient labyrinth had been an image of primeval forest, and of chaos, and perhaps «even of the soul inhabited by monsters» so modern technology had led to «exceedingly contradictory and paradoxical» consequence of neither solving nor overcoming the complexities of chaos but of merely offering the techné of a «rational reconstruction of the irrational», the creation of «a place of loss and fear»; in short, the creation of another – no less fearful – labyrinth.

On July 1, 1942, as Levi was hiding from the fascists in Florence, he penned the extraordinary essay, Fear of Painting, which he read over the airwaves on Radio Firenze on October 25, 1944. When his friend, the publisher Giulio Einaudi, reprinted Fear of Freedom in a new edition in 1964, Levi requested that Paura della pittura serve as a new appendix. The essay addresses many of the same issues first raised in Fear of Freedom. Here Levi uses painting as a prism through which we can see the problem of freedom in a different light.

For Carlo Levi, fascism – in its failed attempt to embrace and sterilize everything – is forced to realize itself in death. Placing itself at the service of barbarism, the negation of freedom, of the instruments that destroy autonomy, and which impose the most stifling conformity and alienation, fascism had thought of itself as the catalyst of history. Instead it proved itself tragically bound by the forces it had unleashed. In making the State an empty but ferocious ideal, Levi argued, it had transformed men and women into dead objects.

Just as that first exiled intellectual, Adam – responsible for putting a name on all things – Carlo Levi seeks in Fear of Freedom and Fear of Painting to put a name on a certain melancholy that ripens into a holy terror, a dumb awe, a trembling before the gods. He intuited the inescapable double bind of modernity: that we must differentiate ourselves from the maternal indistinct chaos in order to be free; but in order to be creative, we must never sever our genealogical ties that bind us to that fertile yet terrifying sacredness.

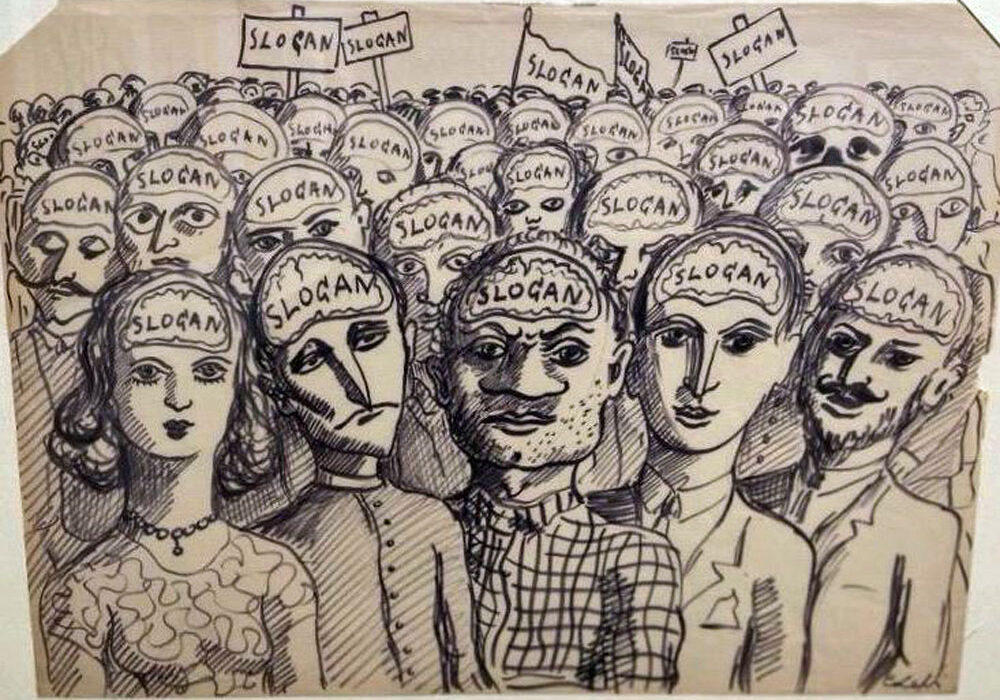

Image: Carlo Levi, Satirical drawing.