A Daunting Discovery: The largest Carabinieri Archives Outside of Italy and a List of 1661 Names Shed Light on a Greek island’s Darkest Moments

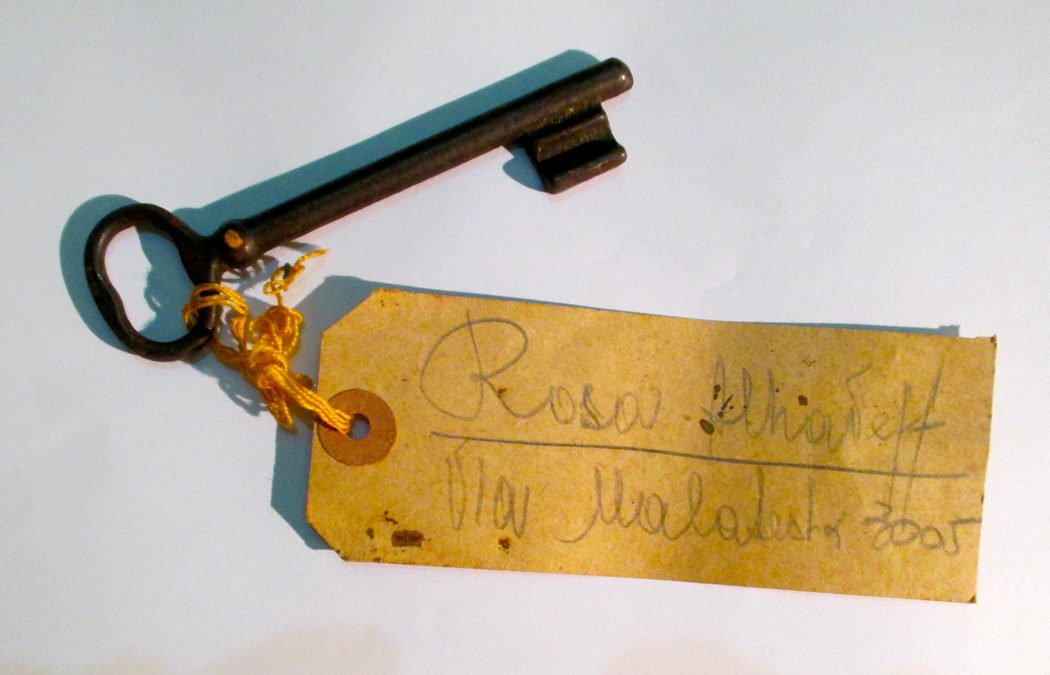

How was it possible? A locked door, unopened for nearly 70 years?: Nobody ever wondered what was behind it, or nobody wanted to know? What was behind that closed door in the building of the Police Headquarters of the Greek island of Rhodes?

Miracle is a big word, but one that the historian Marco Clementi uses when he speaks of that door and its secret behind it, which only recently has been brought to light.” It’s a miracle for I couldn’t believe what I saw”.

The sun stands high and the air is stagnant. The island of Rhodes, far in the south of Greece, lures throngs of tourists to its long beaches even in this summer of national crisis. “I go swimming daily, otherwise I wouldn’t be able to cope,” says Clementi. Reading the letters on yellowed paper in which people are asking to leave this beautiful island seeking asylum somewhere, anywhere: in France, England, Turkey, Africa, or the Americas”. The letters are 76\77 years old: that finally those letters can be read by Clementi is part of the miracle.

Marco Clementi wears a grey t-shirt the color of his hair: Like the dust that has settled on the old papers. At a certain point the contents of the room behind the mysterious door could have turned to dust. That this will not happen and that Marco Clementi will be able to tell a dark chapter of the history of this sunny island during the first half of the 20th century, is due to the perseverance of a former Greek state employee who didn’t tire of stating and finally putting in writing what he knew: that at the main Police Headquarters of the island there was this locked room containing many old files, and that was never aired nor opened and checked the contents.

His letter landed in the local archives. That was 2002 and nothing much happened after that. Not for nearly 10 years, until a new administrator, Eirini Tiliou, was named head of the island’s state archives and the historian Marco Clementi heard about the rumors regarding the locked door while he was carrying on research in Rhodes. “What kind of papers would be there?” he doubtfully thought at the time.

The director of the archives asked for his help. Together they went to the police headquarters after Ms.Tiliou had gotten the necessary permits. “It was a very emotional moment to be able to open the door”, she said later.

Clementi remembers vividly what they both saw: a room with one crumbling wall, and all that was standing against it was irremediably lost. Everything else, however, was intact. Nearly 90.000 documents in bookcases, boxes and brown folders labeled in blue, yellow and red colored pencil. The testimony of a long forgotten, zealous bureaucracy.

These papers cover the years between 1912 and 1946, a period of time when Rhodes was under Italian sovereignty; the occupation of the Dodecanese islands was part of Italy’s colonization policy. But unfortunately, for a short but fatal period, at the end of World War II, the island fell under German yoke.

The documents include information about many of the approximately 100,000 people formerly living on the island: about their social and economic life, their friends and enemies and their opinions regarding the different rulers of the time. A treasure for historians.

Clementi, a historian specializing in the former Italian occupied areas, ascertained that the documents he and Ms.Tiliou rescued in 2013 were archives from the Italian Carabinieri. The largest collection of this kind preserved outside of Italy. More precisely, the documents are records from a special unit of the Carabinieri, a division of the Fascist police, that worked in Rhodes in a similar fashion as later did the German Stasi.

Under the fascist dictatorship, the so-called “enemies of state” were black-listed everywhere including Rhodes: the Carabinieri made files on spies, political suspects, the inhabitants habits and their religion: Muslim, Catholic, Orthodox and Jewish. The files that the Carabinieri labeled “Di razza ebraica” (of Jewish race) and “Comunita israelitica di Rodi” became of great interest to the Germans when they took over the island.

“Impossible” is the reaction that Clementi hears when he informs the Carabinieri archivists in Italy about the archives discovered in Rhodes. Even in Rome no one knew about the records that had been left in the far away island – forgotten or destroyed.

Clementi notes that another Carabinieri archive outside of Italy can be found in Montenegro, but that it is much smaller covering only two years and not 33, as the one in Rhodes.“It is unbelievable that nothing was thrown away during all these years, and the entire archive had landed on our laps”.

There are many historical photos, portraits and family pictures. They are now kept in an old vault protected from natural light, in a building which is in complete disrepair. Clementi spent many months organizing the documents, but he couldn’t ask for funds not even for new filing folders due to the lack of funds at the Greek State Archive.

The Holocaust Museum in Washington has in the meantime begun to fund the cataloguing and digitalization of these documents – at least those pertaining to the former Jewish Community of Rhodes.

The Jewish Community in Rhodes was one of the oldest in the region, with origins dating back to the second century BC. It survived persecution and expulsion by the hands of the Knights of St. John, and although substantially decimated, it blossomed during the Ottoman period.

At the beginning of the Italian occupation the Jewish Community, numbering approximately 4,500 people: at that time, the community thought that it would be able to adjust well to the change of sovereignty, which it did.

The first civil Italian Governor, Mario Lago, made his mark on the island mostly as a master- builder. He brought Italian architects to Rhodes and they built buildings in neo-renaissance style as well as some reminiscent of the Venetian Doge’s Palace.(Il Palazzo del Governo).

In 1936, Lago was replaced by Cesare Maria de Vecchi, who immediately began the restructuring of the palace of the Knights and at the same time removing some facades of many buildings that appear too Turkish in style.

Within a short time the new governor, a fervent follower of the fascist dictator Mussolini, identified some categories of citizens as disturbing elements. In the beginning Greek, Turkish and Jewish teachers lost their jobs and were replaced by Italian ones. Then in 1938, with the declaration and implementation of the “Racial Laws” all those Jews who had become Italian citizens after 1919 had to relinquish their Italian citizenship and leave Italian territory. That affected hundreds of those who had come to the island with the fall of the Ottoman Empire. Within 6 months they were told to leave the island. In their distress the Jews wrote those letters that Clementi has now discovered. They pleaded with the British and French government to allow them to find refuge in British ruled island of Cyprus or in the French colonies of North Africa. It was a factual expulsion, but it saved them from Auschwitz.

On September 11th, 1943 the German Wehrmacht occupied Rhodes (and the other islands) and imprisoned the last Italian Governor, Inigo Campioni. “Thus the island fell under the authority of the German military, but the civil administration remained Italian,” Clementi explains. And these documents confirm it. By then approximately 1,800 Jews had remained on the island.

As if uncovering the documents in the police headquarters was not enough, Clementi also located the records, in the State archive, that document the Italian-German cooperation after the Armistice, thus at a time, when the Italian government had already surrendered to the Allies. One more serendipitous discovery and one more invaluable piece of history. It is a list of 1661 names, typewritten, meticulously numbered, with only the number 181 missing. Whether on purpose or by chance- no one knows.

What we know is that on July 1944 the Germans used this Italian list to round up and deport the remaining Jews on the island. Of the 1767 Jews deported from Rhodes and the neighboring island of Kos to Auschwitz only 163 survived.

Reports by the few survivors describe how they were summoned on July 20th 1944. For three days they were locked up in the rooms and garden of the Italian Aviation headquarter, without food or water. An Italian who was watering his flowers in the garden next door and held the water hose over the wall in order to help, was shot instantly. Only the young Turkish consul was able to save 43 Jews from deportation because of their Turkish citizenship. All others were transported in three freight ships to the harbor town of Piraeus and then further on to a camp in Athens, from where they were packed into trains to Auschwitz. These recollections have long been known.

But that a list existed, on six pages with five columns on each page containing an exact list of the Jews and that was compiled by the Italians none knew. Perhaps only a historical detail, but an extraordinary one, a dreary document of those last days of the Jews of Rhodes. This death-list was typed on the back of the official forms for the registration of birth, the “Elenco delle Nascite”.

“No Italian was ever tried, nor held accountable for any of this”, Clementi says. Where did you find this list in the archives? “In a box of archives, marked 1945”. Not 1944 as would have been correct.

If you plan to pay a visit to the archive and meet Mrs. Tiliou, then expect to take a giant leap over a small antechamber filled with empty boxes. The area under these boxes are now home to myriads of fleas.

Eirini Tiliou —petite and energetic — closes the door to her archive room quickly. The document- filled boxes and the historic folios are piled up as high as the vaulted medieval ceiling. Fire extinguishers hang between the boxes. The air is damp and sticky. “Working here is a health hard”, says Tiliou. There isn’t enough money for either an air conditioning or for permanent employees. That’s why she is usually alone with her treasures in this Branch office of the State Archives of the Dodecanese islands: The Ottoman documents, the collection of Italian architectural sketches, the mountains of papers.

Together Clementi and Tiliou have written a book entitled The last Jews from Rhodes, DeriveApprodi, Rome 2015. The book is also about the Carabinieri Archives. And about other little known stories including those of the two boats (the Rim and the Pentcho) en route to Palestine, that shipwrecked on the shores of Rhodes, not unlike those we see today filled with refugees. They were carrying hundreds of Hungarian, Austrian and Ctzeck Jews fleeing Nazi Germany. After they shipwrecked they were brought and interned in Rhodes. Many of them eventually reached their destination, Palestine, others were transported to the Italian mainland internment camps and escaped the fate of their coreligionist of the island.

The crimes that Germans committed in Greece, the massacres of civilians in villages on the mainland and in Crete, the extermination of the Jews in Salonica, all this has only recently come to public attention. As in Germany, nobody in Greece wanted to know about these atrocities.

Carmen Cohen, who runs the small Jewish community of Rhodes has her office next to the beautifully restored synagogue in the historic old town, well known for its medieval charm. Six synagogues formerly existed, only one has been restored. “Sometimes Greek pupils, who visit the Jewish place of worship, think that they have to take off their shoes, like in a mosque”, Cohen relates. “There is so much ignorance of Jewish religious practices”.

But there are deeply rooted superstitions. When in May in the northern Greek city of Kavala a monument commemorating the 1484 Jews who were deported to Treblinka in 1943 was to be erected, there were protests in the municipal council against the depiction of the Star of David. Some Greeks think of the Star of David as a sign of the devil. The ceremony took place after international protests.

Carmen Cohen is familiar with this. The granite column erected in 2002 in memory of the murdered Jews of Rhodes has been damaged a number of times. The column can be found in the Juderia, the former heart of the Jewish quarter in the old town, between souvenir shops and tourist bars. “Most of the houses and shops here used to belong to Jews”, says Cohen. Today the properties are owned by others, sometimes the city or the state. Cohen thinks that they are responsible for the door having remained shut for such a long time, “until the boxes with the archives would be eaten by rats”.

Clementi offers a simpler explanation to why the secret was finally aired, “the police needed space.”