The national museum dedicated to the history of Italian Jews inaugurates its first exhibition.

On November 14, 1943, eleven citizens of Ferrara were incarcerated in the prison of Via Piangipane. The next morning at dawn, they were brutally killed under the eyes of the population. This was a symbolic and random punishment for the murder of the Fascist local city chief, Igino Ghibellini. It became known to readers around the world through Giorgio Bassani’s short story “Una notte del ’43” and Claudio Pavone’s seminal volume “Civil War.”

On the night that this happened in Ferrara, over two thousand Italian Jews were already locked in trains headed to death camps.

The prison of Via Piangipane, where many antifascists had been interned, became the transit jail for the Jews of Ferrara and for Jews arrested in the area while trying to flee the tight network of Italian police forces, fascist militia, and German S.S. From Via Piangipane, most Jews were transferred to the nearby national concentration camp of Fossoli and from there to Auschwitz.

That very same prison reopened in December as home to the National Museum of Italian Judaism and the Shoah (Museo Nazionale dell’Ebraismo Italiano e della Shoah).

Crowning many years of political and cultural negotiation, MEIS, which is mainly funded by the Italian Ministry of Culture, will be completed in 2020. In the words of its president, Dario Disegni, the museum is designed to become a “Jewish cultural hub, bearing witness of two thousand years of Jewish experience in Italy; to be an open and inclusive space, a laboratory for ideas and reflections on what it means to be a minority.”

A mission that at any other time may have seemed ambitious but straightforward, today, as the idea of Europe grows unstable along with that of national state as we know it, entails significant challenges.

Like many Midrashic and Talmudic stories, the MEIS stems from counterintuitive premises above and beyond the choice of its location. Conceived at a time when the notion of “museum” began to come under critical scrutiny, and dedicated to a topic, Italian Judaism, on whose definition no one fully agrees, MEIS was charged at its inception with the wondrous task of representing twenty centuries of Jewish history in a country that has been in existence for less than two.

As if this was not difficult enough, it was endowed with a fascinating geographic conundrum: to bestow a “national” quality on a Jewish community that for centuries has defined itself within municipal borders, and on a city, Ferrara, that still proudly claims its past as capital state under the Estense rule. While these twists can lead to a productive and needed debate, it remains to be seen how the new entity with its centralizing mission will be able to interpret and value the many Jewish museums, libraries, archives and local histories, that distinguish each Italian city from the next one.

Faced with these complicated tasks, the MEIS’ scientific committee, which also served as curatorial team and is comprised of Anna Foa, Giancarlo Lacerenza and Daniele Jallà, set out to sketch a map that tries to offer orientation in a labyrinth of past history and present politics.

It is not the first time that a museum attempts to retrace the history of Italian Jews.

A memorable antecedent is the New York Jewish Museum’s exhibit Gardens and Ghettos, that offered one of the first opportunities to structure for public fruition research and works of art in the field of Italian Jewish studies. It was 1989 and back then too the effort was collective: JTS art historian Vivian Mann, Tullia Zevi, head of the Union of the Italian Jewish Communities, the Italian Ministries of Culture and Foreign Affairs and the then Mayor of Ferrara, Roberto Soffritti.

In the closing statement of his catalog essay, David Ruderman pondered the unassuming and horizontal nature of Italian Judaism, that, with its tapestry of artistic and intellectual outputs, never established a central authority over cultural, religious or governance matters.

Though mainly centered in the Renaissance, Gardens and Ghettos also addressed the questions of the origins, the transition from Jerusalem to Rome, the relation with Babylon, and the kingdoms and empires within which Judaism progressively changed and defined itself as a modern minority. Its thrust was the relation of the peninsula’s Jews with philosophical, literary and scientific movements as well as with Jews elsewhere.

A closer significant precursor of the MEIS’ exploration of the origins and the relation with Antiquity and the East, is the beautiful exhibit Menorah: Cult, History and Myth. Curated by Alessandra Di Castro, Arnold Nesselrath e Francesco Leone, it was produced, in the summer of 2017 after a decade-long incubation, by the Vatican Museum and the Jewish Museum of Rome. Relying primarily on the exploration of art and text, Menorah offered an unprecedented opportunity to reflect on Judaism through the analysis of one of its most prominent symbols.

MEIS’ opening exhibit draws on these two experiences in limited ways, mostly in the selection of artifacts, and differs from both significantly. Its focus is the first thousand years of the origins. Its driving preoccupation is to define Italian Judaism in relation to the Church and a problematic idea of “Italianità antica,” as eloquently expressed by the museum’s director, Simonetta Della Seta. The exhibition team constructed both narratives with remarkable efficiency and dedication.

What sets the stage for the story is the definition of the Jews as the only minority that was, as the exhibition’s catalog states, “allowed to remain in Christian Europe.”

In their introductory essay Anna Foa and Giancarlo Lacerenza elaborate: “Through the MEIS’ first exhibit, we have decided to show how, in the first place … the presence of Jews in the Italian peninsula changed unexpectedly from just one of the many components of a multicultural Empire to the only one able to resist the passing of time.” And again: “Rome is central to the specificity of the Jewish world in Italy: ancient Rome with its prevalent inclination to tolerance and diversity, and Christian Rome, which adopted parts of that model and accepted the presence of Jews, but of Jews alone. No other minority was able to remain inside Christian society: for heretics and others who were considered “infidels,” the choice was the stake or forced conversion. The relationship with the Jews was unique … not one of tolerance … but also not of complete elimination.”

Defining the Jewish minority status as a condition of simultaneous oppression and toleration—a privilege and a destiny within the Christian world— the curators chose to tell the story of Judaism from the very heart of the Christian society, the one that emerged as dominant from the Roman Empire and that —they suggest— forms the root of contemporary Europe.

The catalog further elaborates this perspective proposing a view of Catholic opposition to Judaism as stemming solely from a theological rationale which – in contrast with the socio-economic motivations that supposedly operated elsewhere – required a measure of empathy. To reinforce this depiction, the exhibit defuses the idea of Jewish self-isolation introducing famous converts, Christians who elected to be Jewish, described as “almost a normal occurrence in the first centuries of Imperial Rome which became progressively forgotten in later sources”.

In the eyes of the curators, the Roman Empire, imagined as the force that virtually absorbed the civilizations of Antiquity —from Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean—is the raw matter of which this Jewish “italianità” is made and its tolerance, however anachronistic such concept might be when applied to the Romans, forged the Church’s attitude and Judaism’s exceptionalism.

The second category in which the development of the Jewish “Italianità” is inscribed is the coalescing of a koiné that produced the vernacular and eventually the Italian language. As the introduction to the catalog explains: “the origin of this specificity also lies in the […] cultural symbiosis, that sees Jews of the Southern peninsula, together with Christians, taking part in the origins of Italian culture”.

The cradle of this linguistic ferment is usually placed in the Southern regions, between Palermo, Lecce and Naples, “a less theologically charged area” where, as the curators explain in the introduction, Jews flourished as an integral component of one culture, yet no trace remained of their presence in modern times.

In and of itself, this beam that, from the prison of Via Piangipane illuminates the land beneath which —in Carlo Levi’s famous depiction— Christ did not venture, creates a short-circuit within the narrative of the exhibit and opens an interesting set of questions for the “laboratory of ideas”.

For the integration that gave the exhibition its title—“An Italian story”— cannot clearly be divorced from the complex history of the peninsula nor from the debates that constitute the nation’s psyche. The candid projection of Jewish continuity as minority over a canvas that is neither continuous nor mainstream undoubtedly offers material for good discussions.

Since the unification of Italy in 1861-70, this southern cradle —also called “Meridione” or “Mezzogiorno”— has been regarded as the poor hole of the nation, home to destitute workers who populated factories in the Americas and Northern Europe, the land of subalterns, where “Italianità” amounted to what Gramsci defined as “revolution-restoration”.

During the centuries in which the cluster of languages that were later codified into modern Italian came into being, this area was the North and the West of the unraveling Eastern Roman Empire, the periphery of the rising Islamic world and the heart of the court of Fredrick II, unmentioned in the exhibit, whose title conjured what following generations would consider an upside-down vision of the world: king of Sicily, Emperor of Holy Roman Empire and of Jerusalem. Not unlike the Southern Jews who, according to the curators, lived through millenia—”without significant ruptures”—this multi-centered world in permanent transformation, not especially representative of the Church or the Romans, remained on the modern geopolitical map, at best as an ornament.

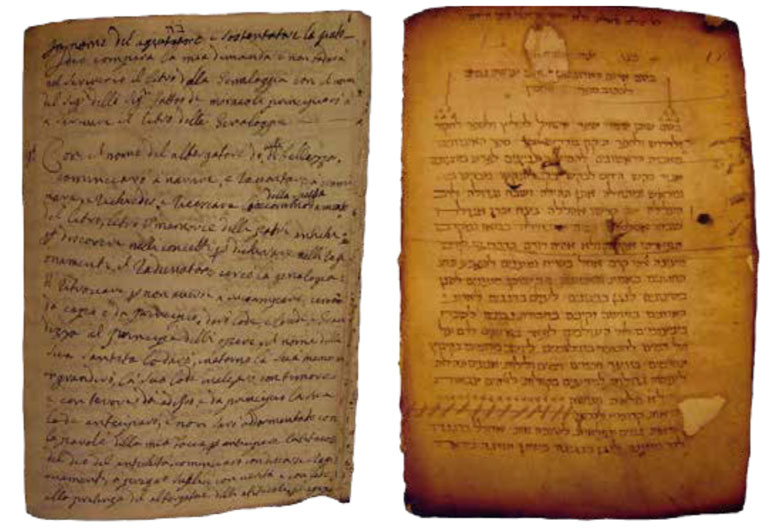

In the pages of the MEIS’ catalog, this southern saga, the linguistic exchange, the wrestling layers of Palestinian and Babylonian Judaism, the revival of the Hebrew language and the wealth of Hebrew manuscripts originating in the peninsula, are an unparalleled testimony to the way in which Judaism became part of the modern West. For the purpose of the exhibit these southern treasures are primarily the vessels through which “Babylonian Talmudic culture entered Europe” and “the culture of the Jews who settled in Imperial times in the peninsula, became the cradle of European Judaism.”

The catalog’s foundational narrative, which shifts, between chronological and geographical grids as well as between the Italian and European horizons, ends with the 10th century plus a long self-standing coda devoted to Benjamin of Tudela. It comes full-circle anticipating the next thousand years and the fall from heaven which ends the southern story: “the first crisis in this coexistence, came later, from the North, in the echoes of the irreparable damage caused everywhere Jews lived after the massacres of the First Crusade in Germany, after a wave of apocalyptic violence took over the Christian world.”

For all the challenges the span of time and space this exhibit may have entailed, the MEIS’ curators chose to stay within an understandable comfort zone, gazing at the periphery from a center they regard as undisputed and trying to meet the public where they believe it stands.Yet, browsing some of the essays and looking beyond the lens of the lead theme, we can catch a glimpse of remnants of a world that does not fit a linear historical narrative nor the interpretative aspirations of a museum. Here and there, perhaps by pure chance, the reader is let to imagine what fragments of different centers may look like if observed from various points of the periphery.

One more consideration is due regarding the global stage of which the MEIS is inevitably part. The MEIS’ concern with Europe’s roots and the place of Judaism in the Christian epic echoes a larger trend that perhaps museums are especially apt to capture. The “thousand years of history” that catalyze the Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw are not the same thousands covered by MEIS but play a similar function in relation to nationhood and rootedness. On the American side, the Bible Museum opened in Washington and is advertised as the “Ark of the Covenant for our nation.” It may be interesting to look at these projects comparatively and see what light they may shed on one another, even if it were only a matter of esprit du temps.

There is clearly food for thought in this first stage of the “laboratory of ideas” the MEIS is designed to be. Some has to do with content and the representation of Ancient Judaism for the non-Jewish world as well as for the many facets of the Jewish world. Some with method and meaning and the interaction of hermeneutical tools from different traditions (the exhibit curiously raises the question of limiting the use of talmudic and midrashic material considered somewhat unfit as historical source). And finally, some with the ambiguity inherent to the notion of museum whose mission of “collecting, displaying and interpreting” does not satisfactorily distinguish modern institutions from what Titus did in the Temple of Peace.

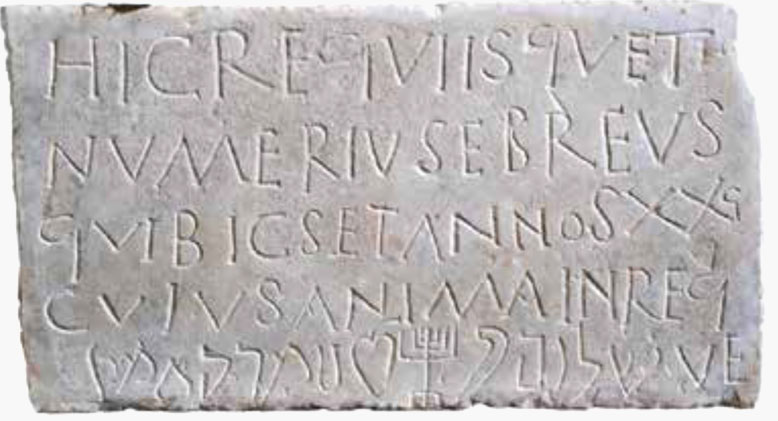

The curators’ statement that the exhibit is made of “books and stones” symbolizes well this ambiguity and will hopefully serve as hot bed to discuss the possibilities and limits of a public space for history.