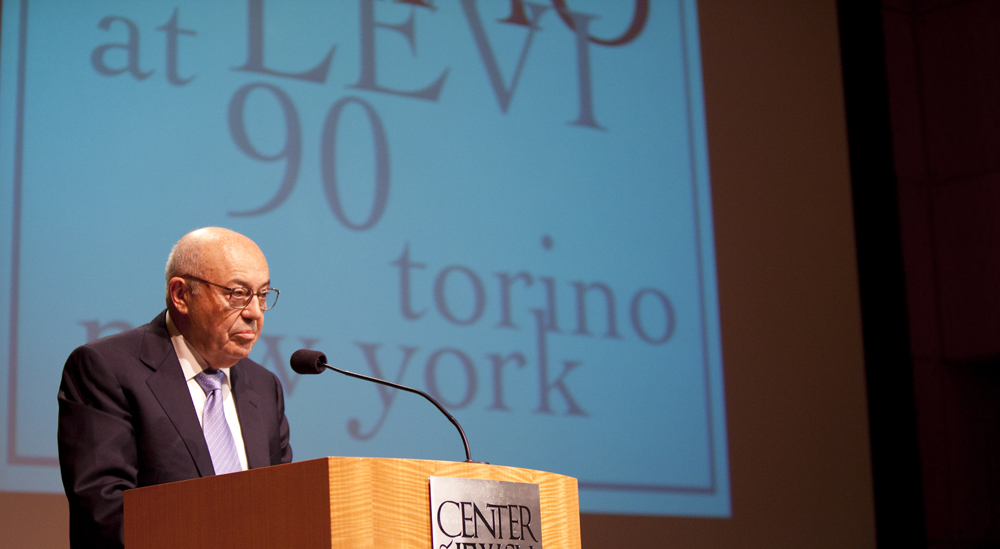

Opening remarks at Third Annual Symposium on Primo Levi

I feel both honored and inadequate for the role of opening this symposium since I am neither a literary critic nor a historian. Still I have read practically all of Primo Levi’s writings and have spent more time with my first cousin’s husband than probably anyone here. So I accepted the invitation to speak as one who had had the good fortune of enjoying his company at various times over a period of nearly four decades.

I first met my cousin Lucia’s new husband at my Bar Mitzvah in Turin in 1948. I had already known of him for at least a year. And when my mother received from her sister a copy of the first printing of “Se Questo e’ un Uomo” in 1947, I assisted my father with an awkward English translation of its first chapter. Its intended recipient was Boston’s renowned literary rabbi, Joshua Loth Liebman, author of the highly successful title “Peace of Mind” which had enjoyed a long run on the New York Times book list. I don’t recall how the good rabbi was enticed into meeting with two members of Boston’s tiny Italian Jewish community, my father and Anna Foa Jona, Primo’s first cousin. In any case this first attempt at introducing Levi to an American public came to naught with Rabbi Liebman’s assurance that the public (presumably including Jewish readers) had heard enough of the Holocaust and such a book would never find an audience. Whether or not he was correct, my young mind was affected strongly as the entire text was read to me by my father.

A step back for clarification. My parents, Achille and Maria Viterbi, and I, their only child, left Italy in mid August of 1939 as a consequence of the Racial Laws. After two years in New York City, we settled in Boston where my father, formerly the chief ophthalmologist at the major hospital of Bergamo, restarted his truncated career, opening a practice at nearly sixty years of age. But my parents’ heart and spirit never left Italy. For at least the next twenty-five years the primary lifeline to their former homeland was the weekly correspondence between my mother and her five Luria siblings, all born in the mid-size town of Casale Monferrato, located about midway between Turin and Milan, but very Piedmontese in dialect and character. Her closest sibling, in age, temperament and warmth was Beatrice (known to me as zia Bice). Her husband, Giuseppe Morpurgo was a highly respected professor at a Liceo in Turin and a much published author of school books and of Jewish themed novels, most notably Yom Ha-Kippurim, the chronicle of a mixed marriage. During the era of the Racial Laws, zio Giuseppe was the Principal of the Jewish School of Turin, which provided an education for the Jewish children barred from attending (and polluting!) the schools for Aryan chidren. Zia Bice and zio Giuseppe and their unmarried twin daughters spent the years of Nazi occupation in hiding among the good and reliable peasants of the high Piedmontese Alpine country. Returning to their home at war’s end, they began the cycle of correspondence with the news of how all family members had survived the Holocaust. Not long afterward came the news that both the twins, Gabriella and Lucia, had become engaged, the latter to the chemist and Concentration Camp survivor, Primo Levi.

Three years later, as I turned thirteen with only the slightest exposure to Hebrew prayer practice and no relatives nearby, we came for the summer to Italy to celebrate my Bar Mitzvah among a host of aunts, uncles and cousins. Only zio Giuseppe with his Jewish community credentials could secure the tutor for a crash course in Hebrew and ritual and obtain rabbinical approval in spite of my limited religious preparation. So that was the occasion where I first met Primo. I must admit that though he was already a celebrity within the family, I was so nervous and focused on my challenging task that I was hardly aware of him. On the other hand, my father, a renaissance man with wide cultural interests, was much impressed by this brilliant young man and engaged him in extensive conversation.

Little more than a decade later, having moved to California to work in the space program and married, I returned to Italy with my wife, Erna, who was expecting our first child. Having participated in the first successful U.S. satellite launch, I was invited to lecture in England, France and Italy. We visited the whole family including, of course, uncle and aunt Morpurgo and their daughters with their families. Recently, my primitive 8 mm. films from that trip were digitized and I viewed scenes I hadn’t seen in several decades. The moving images of the whole young Levi family, Primo, Lucia and both young children standing on the narrow balcony of my aunt’s apartment startled me bringing back cherished memories. Our next visit to Italy was of much longer duration. In 1967 and 68, taking a sabbatical leave from my UCLA faculty position and spending most of it at the Milan Polytechnic, we visited my aunt in Turin a few times. On each visit, Primo and family would come by and we would exchange the latest family happenings and catch some glimpse of Primo’s latest literary output. I also recall on those occasions the kindness and respect shown by Primo to his in-laws. Our travel to Italy became ever more frequent over the subsequent years. On several of these visits we were invited to the Levi apartment on Corso Re Umberto, where I best remember Primo’s study filled not only with books but with hanging mobiles which he fashioned himself. Over the years, we developed a warm relationship, occasionally discussing scientific matters.

Beginning in 1967, my father having passed away the previous year, my mother came to visit her beloved sister Bice nearly every summer for the next dozen or so years. Part of each visit, along with another sister and brother, they spent “in villegiatura” at a modest pensione in Frabosa Soprana, a village in the lower Piedmontese Alps. Primo’s mother was occasionally their companion. One time in the late 70’s, both the entire Levi family and ours visited there at the same time and stayed briefly at the pensione. There we had the pleasure of meeting not only Primo’s mother but his sister, Anna Maria, and her husband, an American film script writer exiled to Rome’s Cinecitta’ as a victim of the infamous Hollywood Blacklist during the McCarthy era. My brief conversation with this colorful and direct American brother-in-law of Primo would have seemed more natural back home in Los Angeles than in rural Piedmont.

My most vivid recollection of Primo was our last encounter, both because of its length and the circumstances. This was in April, 1985 during Primo and Lucia’s only visit to the United States. Much of this visit, with its intense book tour schedule, has been chronicled in biographies of the now renowned author. What I can add is that the few days in California spent with family provided something of a respite from the crush of admirers that surrounded him throughout the tour. After a day or two in Los Angeles where along with meetings with film industry figures, they visited Lucia’s and my mutual cousins (who had arrived in the U. S. at almost the same time as I). Then my wife and I picked them up and drove them the hundred or so miles to our home in the San Diego area. There they spent two days. The main attraction was a visit with my overjoyed 91 year-old mother. But we also arranged a brunch for Primo to meet some of our university community’s chemists and historians, most notably H. Stuart Hughes, an emeritus Harvard history professor, who was spending his retirement years at UC San Diego and writing his memoir. Hughes had at one time been the “Peace and Freedom” party’s candidate for the U.S. presidency, but more successfully had written the monograph “Prisoners of Hope” recounting the stories of a half dozen Italian Jewish authors, including Primo, Carlo Levi, Natalia Ginsburg and Giorgio Bassani. That encounter was not particularly memorable, but another guest at the brunch, my next door neighbor, Professor Gustaf Arrhenius, grandson of one of the earliest Nobel laureates in chemistry, recalled the meeting and my relationship with Primo for years afterward. From San Diego we drove with the Levis to Claremont, a college town about a hundred miles to the northeast, where he was to lecture. On the way, Primo spoke to us of the manuscript of “The Drowned and the Saved” whose galley proofs he was correcting at the time. Needless to say, his lecture at Harvey Mudd College on the subject of the book was outstanding not only for its content but as well for his delivery in fluent if accented English. He even handled the Q&A in English, after an abortive attempt to insert a translator who was not up to the task. We left Primo and Lucia in the comfortable visitors’ living quarters and the kind hospitality of the Hillel rabbi of the college. After they returned home we corresponded a couple of times, the last time within days of his death.

The foregoing are the plain facts of my interactions with Primo Levi, my first cousin’s husband. Words are not adequate to describe the essence of the man. I can only say that he was extremely kind, warm, thoughtful and more sociable than how he is usually described in innumerable articles and books. I was indeed fortunate to have interacted on a human level with the remarkable individual whose memory and literary patrimony we honor tonight.