Remove from Circulation.Fascism’s Suppression of Jewish Authors

Research shows that anti-Semitic censorship has historically been an important facet of the persecution enacted against the Jews and that the eradication of books has usually been the prelude to the purge of their authors.

Both Germany and Italy attempted to rid their culture of its “Jewish” element. While their goal was the same, their paths have been entirely different. The Nazi ’s relayed on populistic and spectacular methods like the book burnings that took place in May 1933, while the Italian regime ’s censorial action was carried out cautiously, even furtively, but was just as thorough and effective. Between 1938 and 1939, the works of authors of Jewish descent (writers, journalists, playwrights, composers) were almost completely banned from the Italian cultural scene, including those written in collaboration with “Aryan” colleagues.

The final outcome of this book cleansing was massive: with rare exceptions, publishers eliminated Jewish authors from their catalogues, and the police seized hundreds of thousands of volumes including manuscripts and galleys.

Compared to other censorial actions, the one against the Jewish authors had a peculiarity. While traditional censorship bans books based on their ideological or political content, considered “dangerous” or “undesirable,” in the case of Jewish persecutions, eliminating ideas from the public forum was not the primary objective. The writers were the real targets, and they had to be indiscriminately struck because of their “race”. So, while at the end of 1938 Nazi Germany enforced the compilation of lists of works “deleterious and undesirable” and only subsequently a list of their authors, in Italy, from the first unofficial orders given in April 1938, lists of authors were compiled within publishing and academic circles.

One of these lists – the only one made public at the time – included 114 authors of school texts and was enclosed in a dispatch of the Minister of National Education dated September 30, 1938 and issued on October 6. After expelling Jewish teachers and students from Italian public schools, it was now the turn of books. At the start of the new academic year, “Aryan” students could only be with “Aryan” classmates, study under “Aryan” teachers, and therefore have “Aryan” books.

The Ministry of Popular Culture prepared a much more extensive list of authors that was kept within close circles. In 1942 this list was made semi-public and released to publishing houses and prefectures, respectively responsible for “self-cleansing” their backlists and for inspecting and seized books. The list was also forwarded to libraries so that those books could be taken off the shelves and out of circulation. There were about 900 names, both Italians and foreigners, for the most part “of Jewish race.” The new list also included a small group of political opponents to the Fascist regime who were not Jewish.

Fascist censorship against Jewish authors was a wide and complex action. This was both due to the larger number of authors in all fields and to the accuracy with which the regime sought to involve public and private institutions in the book cleansing. The process was initiated by the Ministries of National Education and Popular Culture and spread to the local prefectures, provincial police headquarters, publishing houses, newspapers, schools, and libraries. A large number of individuals were involved in different roles in censorial procedures: bureaucrats, policemen, publishers, booksellers, librarians, principals, teachers, academics, etc.

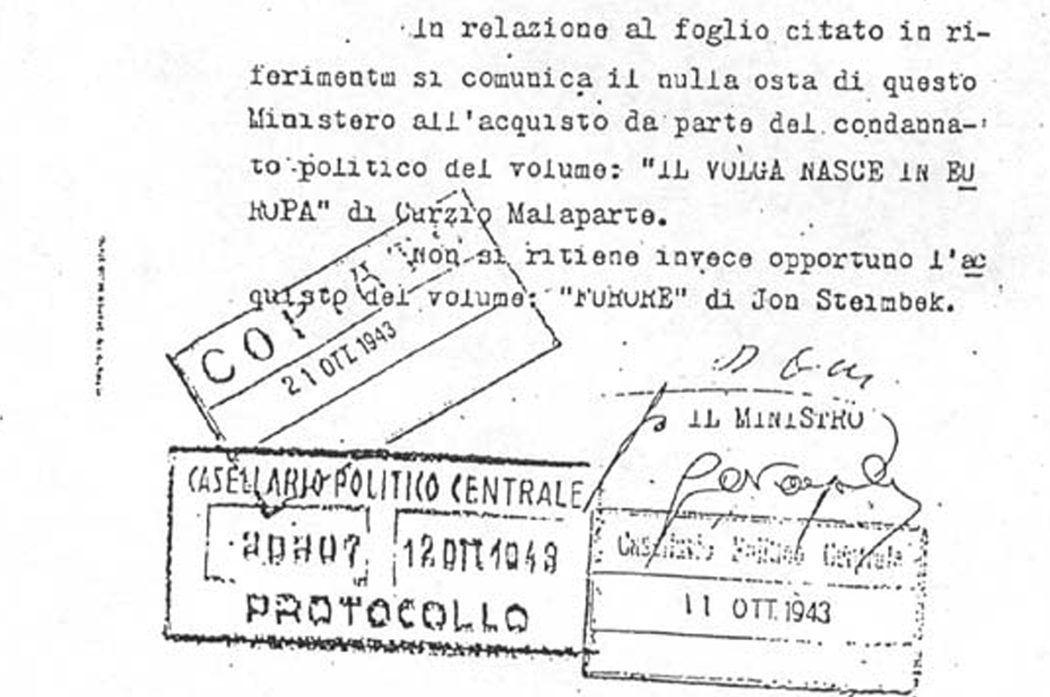

Another element of complexity arose from the different policies on racial censorship taken by the two Ministers Giuseppe Bottai and Dino Alfieri between 1938 and 1939. The National Education Ministry immediately (September 1938) and publicly banned Jewish authors of school texts; this measure was implemented by a law issued two months later, in November 1938 (RDL 1779, art. 4). While the Ministry of Popular Culture imposed the total ban on all Jewish writers only a year later, in August 1939, after being given a secret order directly by Mussolini but without any form of legislation. It seems that the Fascist authorities sought not to upturn the status quo abruptly and to operate by means of word of mouth and by informal orders. By avoiding decrees and written laws, the regime also succeeded in minimizing public awareness and the paper trail.

With the almost complete elimination of the Jewish presence in the Italian publishing landscape Italian citizens of Jewish descent were eliminated from the intellectual life of the country with a tremendous loss of men of letters, historians, jurists, economists, composers, journalists, and scientists. The concerned both books already published (since 1850!) and works to be published. There were some exceptions, but they remained as such.

This process was facilitated by a number of non-Jewish intellectuals who either participated in or chose to ignore the ostracism against the Jews. Among them was the renowned philosopher Giovanni Gentile, a leading Fascist scholar, who as owner of the publishing house Sansoni – fully complied with the censorial orders with out any public display of disapproval. Unlike Gentile, another representative of Italian idealism and anti-Fascist sympathizer, Benedetto Croce refused to provide a list of “Jewish” colleagues and criticized the Fascist censorial policy. In 1940 Croce intervened with the government in support of the Bari-based publishing house Laterza, whose owner had refused to purge his catalogue consequently suffering a massive book confiscation. A few days later the ban was revoked by Mussolini himself.

Recent scholarship and findings on archival sources have brought to light how the Fascist regime is Italy silently carried out a thorough censorship plan with the widespread compliancy of bureaucracy, publishers, and intellectuals. Only in 1998 a complete reconstruction of the Fascist regime ’s book cleansing was made available with the landmark book of Giorgio Fabre, L’Elenco: censura fascista, editoria e autori ebrei.