Nicola Chiaromonte, The Partisan Review, February 1948

We had been at school together, at the Collegio Massimo, the time-honored Jesuit college where the sons of the Roman middle class sit in the same classroom, but do not mingle, with the scions of the "black" aristocracy*. We had been together responsible for a collective act that consisted in greeting the teacher of French with the word Scythian whispered by thirty mouths, and also for the editing of a mimeographed school magazine, an initiative which was strictly forbidden by the Fathers. We had played soccer and exploded homemade land mines in the same vacant lot. We had both been in love with Pearl White and had done many irregular and dishonest things for her sake, like selling textbooks and stealing from our fathers' wallets in order not to miss the next episode of The Mysteries of New York. But when we were fifteen our roads began to part: Martelli went into the Catholic Youth and embraced the ideology of the Partito Popolare (the pre-Fascist version of the Christian Democrats), while I was for D'Annunzio and (because of D'Annunzio) also for Mussolini. In the meantime, I had also begun to disbelieve in God, and more especially in the necessity of submitting to the torture of weekly confession, while Martelli remained a devout boy and went into retreat every year to perform Saint Ignatius's Spiritual Exercises under the direction of a very old Father, famous all over Catholic Rome as an outstanding specialist in that kind of devotion. As a consequence, Martelli and I could not be intimate any longer, and in fact we started having different friends. But our ideological quarrels remained a strong bond between us, especially since from politics we had both rushed into theology. It was Saint Thomas against Nietzsche (or, rather, Zarathustra), and Nietzsche suffered many logical defeats; at the same time Martelli consistently beat me at chess. By then, we were not friends any longer, and if I saw him from time to time, it was mainly to test some newly discovered idea or argument against his skillful adherence to tradition. Sometimes, he would suddenly interrupt the argument and, looking me straight in the eye, announce that he was praying for me. To which, what could I answer except "Thank you"? Then, at seventeen, Martelli told me that he was going to become a Jesuit. A year later, he entered the Novitiate. I did not see him for three years, and when he emerged from his seclusion he had undergone a weird mutation. There was simply nothing spontaneous about him any more; behind every one of his acts and gestures there was premeditation. It was as if his innermost being had been submitted to an uncannily thorough process of plastic surgery. "Like a dead body, like a cane in the hand of a blind man": the aim starkly set by Ignatius in the chapter "De Oboedientia" had been attained in him, too. The adolescent, the young man, the defective human being, had been corrected, straightened, stamped into a fixed shape, made into a dependable spiritual tool. Of Martelli as I had known him only the outer shell was left, and not even that, since his countenance and gestures had also changed. No other organization, I thought, could get that much from a man, simply because no other organization would care to work on an individual so exhaustively. Certainly not a political party, and certainly not the state, either, however totalitarian. The conditioning of youth by the Fascist regime looked silly indeed when compared with this sort of achievement. I found myself without any means of communicating with my old playmate, and I was able to talk to him only in distant and vague terms or else by treating him as the emissary of an evil power, the Church, and getting angry. The rare times we saw each other, I did not know what to do except to be polemical on the subject of the Church prostituting herself to Fascism. He answered that it was a mistake to judge the Church on such trivial grounds and that, anyway, if he was sorry for some of the things I said, he couldn't help feeling glad that I could get so passionate about Church politics: that was not a sign of indifference, was it? As for Fascism, he didn't like it either, but if the Church could advance her aims a bit because of Mussolini's megalomania, that consoled him for many a sad aspect of the situation. The point was that, being a Jesuit, he couldn't become excited about current events any longer; the real battle, the only one about which he could feel passionate, was being fought on a different level. Then Martelli would start talking about modern man drifting away from the Church, and the doctrines that were responsible for it. At that moment I would feel utterly bored and incapable of arguing; the line was too musty, and too preposterous. Once, I tried to cut my opponent short by reminding him of Flaubert's saying, in 1850, that "our soul is a sealed book to the clergy." That, I said, had been true for some time before 1850 and was an irreparable fact, even if we had to admit that we didn't know what consequences would result from it. "That is what I call drifting," retorted Father Martelli. "You call it freedom, I suppose. To me, this kind of freedom, as Plato will tell you, evokes its opposite, tyranny. If you don't have spiritual order, you are bound to get a police state of some sort, because society has to be kept together. The individual might imagine that to follow one's whims and mean well is a sufficient rule of conduct. But society is dogmatic by its very nature. Moreover, to take the only people I know, the Italians—I don't see that their souls are such a sealed book to us priests. It might appear to be so in the cities, because nobody knows what is going on in the cities, anyway. But, I assure you, in the cities and elsewhere, people keep coming to us, and not just to hear Mass, but to tell us something about their souls and bodies. Not as many as one could desire, I grant, but quite a number. "We may be wretched soul readers, but we look after things in the life of the people that nobody else seems to care about. There is no substitute for the parish priest. All is not well with religion today. But the fact is that hardly anyone refuses to have his children baptized, and hardly anyone refuses a religious funeral, either. For us that is not enough, but at least it indicates that the Italians are still Catholic. We reject the distinction according to which ritual observance indicates only some kind of vague attachment to tradition, and the idea that, since people do not always follow the Church in politics, they have necessarily parted from her. As long as people will come to us to be married and to have their children baptized and their dead commended to God's mercy, it seems to me that it is your belief that is put in question, and not our faith. "In other countries, Catholicism may be bolder or intellectually more refined, but it is in Italy that it is most concrete, that it is deepest in social life. It is in Italy that 'Christian' is synonymous with 'man.' The Church is very much like the family or the native village for us Italians: not an idea, but an attachment that cannot be broken, because nobody can get away from his memory. You intellectuals have gotten into the habit of damning your own people for that, saying that Italy is a wretched country because she didn't have a religious reformation, or a social revolution. As for me, I admire God's work in Italy : how lasting, successful, on the whole, Christian Catholicism has been in civilizing the Italians, that is, taming the beast in them. If, as you say so often, Fascism is bringing Italy to her ruin, then I am confident that in the hour of trial, between Italy and ruin, there the Church will stand." I soon learned to listen to Father Martelli without arguing, simply to instruct myself in the Catholic mentality and logic, much as I would read Civiltà Cattolica, the Italian Jesuit monthly, or L'Osservatore Romano. Outside Italy, intellectuals are inclined to think that modern science, modern philosophy, modern civilization give them the right to be through once and for all with the Catholic question. In Italy, Catholic ambiguity is an ever-present fact. Neither sound logic nor stark political power seems quite to the point in combating it. One discovers Catholic casuistry just below the surface of Croce's neo-Hegelianism, while the space of the afterlife, even when no longer populated by angels and devils, is still an efficient cause of everyday conduct, accounting for much that is inert in Italian life but also for much that is gentle and humane. As for politics in Italy, the liberal state failed entirely to establish on anything like clear intellectual and juridical grounds the supposedly clear principle of the separation of Church and state. Fascism saw the point. But even more significant than Fascist appeasement of the Vatican was the fact that the atheist Mussolini was no sooner in power than he found himself flanked by a spiritual adviser in the person of Father Tacchi-Venturi, S.J., the "Black Eminence." Confronted with such a state of affairs, a non-Catholic Italian is tempted to take a moderately skeptical, and moderately realistic, view of human affairs. But realistic skepticism, especially of the moderate kind, is an essential component of Italian Catholic mentality. Then, since moral and logical laxity seems to characterize Catholicism in Italy, moralistic rigor and sectarianism might seem more pertinent and more efficacious. But rigor and sectarianism require some sort of dogma, and how could a dogma be really anti-Catholic in Italy? When one has received a Catholic education, like me, one is made sensitive to such questions, and the difficulty of finding an answer to them becomes very fascinating. That is why I went to converse with Martelli, and submitted to such seemingly unrewarding exercises as reading Catholic literature and carefully scrutinizing papal Encyclicals. In a way, I was still looking for the politico-intellectual move that would end the intricate game between the Italians and Catholicism with an indisputable checkmate. I left Italy in 1934 and did not go back until 1947. Meanwhile, I heard regularly from my Jesuit acquaintance at Christmas and Easter, when he would send me good wishes, prayers, and invitations to prayer. I couldn't, in turn, resist the temptation to send him a postcard from Madrid in August 1936. As for Martelli's personal history, I knew only that the Order had chosen him to be a parish priest, rather than a teacher, a scholar, or a publicist. That seemed to me a sign that certain personal qualities I had known and appreciated in him, and more especially a sincere evangelical spirit, the desire actually to serve and help people (if he had not decided to be a priest, I fancied, he would have become a Communist), had remained dominant in his character. During the war, I imagined Father Martelli ministering to the poor, organizing relief, giving one of those examples of self-denial that compel admiration and are really what keep the Church going, postponing time and again the retribution that would otherwise be coming to her, as it comes to other mundane outfits when they lay their bets on the wrong horse (and the Vatican surely had gambled on Fascism with some insistence). Back in Rome, however, the first news I got about Father Martelli was that he had become an eminent exponent of the trend known as "neo-Fascism." A friend of mine had heard him preach one Sunday. The sermon was on the parable of the watchful servants and what follows—how Jesus came to bring fire and discord to earth, not peace (Luke 12:35-43). But the orator had spoken mainly on "authority," and my friend professed to have been truly scared by his ecstatic vehemence. The thesis was that authority is the supreme manifestation of God's will on earth; in inner life as well as in public affairs, Divine Truth reveals itself to man essentially in the form of imperious command; where there is no authority there is no truth; hence, the duty of Catholics in the present time is to pray and work for the restoration of authority, which had been reduced to rubble along with moral, economic, and national life. Instead of being surprised by the news, I was struck by the fact that such an appeal was bound to sound solemn and inspiring in the Italy of March 1947. Even when they are patient with him, Italians are basically contemptuous of the priest who falls in with the powers-that-be: he looks superfluous and lackadaisical to them. But a priest who seems to go against the current, and to be free from temporal bondage, will sound apocalyptic and is sure to find an audience. (One limiting factor, in the case of Father Martelli, was the fact that his church was situated in a middle-class section; Jesuits don't cater to the mob.) And, as it happened, the Italians' newly recovered freedom, although enjoyed by everybody, including Fascists and Communists, was generally felt to be either precarious or provisional. Moreover, while the word authority, with its derivatives, was officially taboo, and the fact authority practically nonexistent so far as government prestige was concerned, the question of it hung over everybody's mind and found at best no definite answer. The striking feature of post-Fascist Italy is how little Italy has changed. To be precise, the Italians have refused to be changed by events. They have refused to become bitter, somber, or niggardly. They have kept up appearances as prescribed by one of the basic unwritten laws of the national behavior, a law that is founded on the general disregard for any clear-cut distinction between appearances and reality. There is nothing stoical in the Italians' keeping up of appearances; quite the contrary. It means a certain naturalness, an unwillingness to curb normal human habits and incentives. There is no emergency that justifies losing sight of the values of everyday life. When such a thing happens, it is really bad. The Germans, the bombings, hunger, the battles were bad enough. But they were exceptions. The rule: normal life with its normal components, from money-making to daydreaming, is never lost sight of, and couldn't be, since it appears to be one with nature itself. (In fact, to the Italian mind, war and the other man-made catastrophes come not from the human world so much as from the realm of nature; it is natural that, from time to time, man should lose control of events.) Battles had hardly died down in central Italy when young and old men took over, picked up wrecked trucks, tires, screws, and nails, anything that could imaginably be put to use. During the last weeks of the siege of Rome, while the city was actually starving, in the poor sections people were feverishly busy repairing and improvising all kinds of contraptions for the expected black-market boom; only American supplies were needed to round off the job. One of the leaders of the resistance in the north tells, quite incidentally, in his memoirs that he took a few days off from the struggle to go to Trieste to pick up his family and take them back to Milan, where he had found an apartment—apartments were awfully scarce. And family life surely has a priority in Italy. In the same book, the reader is told that at one moment the commander in chief of the resistance, Parri himself, grimly announced to the assembled Committee of National Liberation that if his wife were arrested he would give himself up to the Germans. Hence, from then on, the fate of the resistance movement was dependent on, among other things, Parri's family. The decision, Parri had added, was the outcome of an agonizing moral struggle. Which was certainly true, but it also meant that in Italy not even the conditions created by the Nazis could persuade a man who otherwise accepted their challenge to make his commitment unconditional. Italy is no place for categorical imperatives. While doing one thing, an Italian always keeps an eye on something else; sometimes it is a sentiment, sometimes a dream, often a strictly personal interest. This makes people say that Italians are realists. To be sure, Italians are a practical people, even if not exactly pragmatic or dedicated to efficiency. But they are realists also in another, more maddening, sense. Their view of things can be desperately trite, tied down not to facts so much as to details and details of details. They care infinitely about the tangible world. One should not forget the sense in which Leonardo and Galileo can be called realists, and which also is Italian. In any case, the most lonely Italian is certainly the "idealist," the man who is seized by one idea and carried away by it, heedless of consequences, because he wants a real "change." Italy has not changed. The rich have become richer; the poor, poorer. The pitiless law according to which it is natural that those who are at the bottom should be miserable and good and those who are on top satisfied and wicked still dominates Italian life. In the collapse of Fascism, only Fascism has been refuted. Fascist authority and state structure are not there any longer. But, if the façade has crumbled, everything that was behind the façade before is still there, very much the same. Except that everything looks like the scattered fragments of a scattered society. Everything is in a state of suspension: conservatism together with the need for change; authoritarian habits along with libertarian impulses; nationalism and the natural cosmopolitanism of the Italians. Political freedom, as it exists today in Italy, is a state of suspension. But still it makes .a difference. The simple fact of free speech has given the country an animation which looks like a new life. Misfortune has made the Italians feel united as they never felt before. The country is far from inert. Yet the apparent immutability of Italian society weighs everybody down. On the large-scale level of politics, everything that has happened could have been predicted by the most commonplace imagination: the strength of the Communists, the dominating role of the Catholics, the practical inexistence of the "liberals." In fact, anybody who has tried to concoct something new in Italian politics has finally come to grief: the intellectuals of the Action Party, who thought they had to offer a new synthesis of liberalism and socialism; and the demagogues of the Common Man Front, who tried a peculiar mixture of the old-fashioned and the colloquial. It is true that the war and foreign occupation left the Italians with a limited, and somewhat prearranged, number of choices. It is even truer that Italy, like all Europe, has been thrown on a rock bottom of hard facts. Against hard facts, as everybody knows, clever formulas are of no avail, though it is felt for some reason that traditional patterns (or vested interests) help. The new realistic school is triumphant. Except that in Italy realism is no news; it always meant cynicism. And a strong man at the top. The point in today's political realism is that it turns political life into a question of mass inertia, not of change. Realpolitik necessarily feeds on mass habits and embedded traditions, not on new ideas and spontaneous surges. In fact, its efforts must be continually directed toward mobilizing the first and sup-pressing the second. It must consistently follow the logical pattern of the movie producer who maintains that bad movies are made by the public, not by him. To the Realpolitiker, the issue as it comes up or exists in social life is never primary; what is essential is what was there before: the vested interests, the reliable inertia of habits. The monarchy should be abolished, but to start with we must compromise with the monarchists; self-government is the goal, but bureaucratic tradition is a fact: we must let bureaucracy have its way until further notice; we want the Church curbed, but it is imperative that we don't alienate the churchgoers, hence let's give the Church what she wants now. In Italy, these arguments have all been employed by the Communists at one time or another. But the kind of reasoning such arguments represent is by no means the monopoly of the Communists. When Togliatti arrived from Moscow, in 1944, to become a Minister of the King, it was not only a temporary deal he brought with him; he was bringing back to Italy the Golden Rule of Italian politics, which had been shaken by events. The fighting, Allied rule, and the cold war did the rest. Today, the Italian ruling class is thoroughly alive to the necessity of being "realistic." (Togliatti is universally regarded as a political genius. Until recently, conservatives were likely to tell you that he could become "a second Giolitti," an admirable liberal-conservative statesman, that is, if only he wanted to. It so happened that Togliatti wanted them to believe precisely that.) The result is that, if one eludes the adventure of Communist conquest, the Italians, after a disaster that has completely changed the terms of their national problems, are being shown by their leaders only one clear path, the path that leads back to the traditional ways of their society. The most recent tradition is, of course, Fascism. It is not by chance that the Communists are diligently following the blueprint of Fascist conquest: armed squads, punitive expeditions, and so on. There are no two ways of doing the same thing, and why bother to invent new methods, anyway? Aside from that, there is the fact that nobody seems to know exactly how to avoid going back to the fundamental propositions of Fascism : state authority, state corporatism, and nationalism as a cement. Very few people are Fascists, of course, and everybody wants caution above all the dangers are too many. And what institution can, in Italy, give a better guarantee of caution than the Church, the locus of all tradition and of all prudence? If Italy goes authoritarian, the Church will palliate authoritarian harshness, as she did under Fascism. If democracy wins, she will see to it that it is accompanied by the right dose of authority. In Italy, the Church offers not heaven so much as protection from the sheer impact of history. And she has recently acted quite effectively as an intermediary between the defeated nation and the great of this world. Italians are, indeed, bound to feel protected by her. In this respect, at least, Father Martelli had been right. I went to see him in his church. It is a horror of a church, built in a kind of streamlined Romanesque style which is the religious equivalent of the somber emptiness of Fascist official architecture: a parallelepiped of bricks laid flatly on the ground and flanked by another parallelepiped of the same material, but standing up, since it has to represent the church tower. The heart of the malicious infidel cannot help rejoicing at such a prodigy of structural insincerity. Martelli's office, however, was a plain whitewashed room, mostly empty, showing all the signs of exemplary Jesuit parsimony. There was the same implacable dreariness I had known in college. Martelli had by no means tried to make his bourgeois parishioners feel at ease in there. Of the things I had imagined about him from afar, one proved to be right. Namely, he had clearly worn himself out with work. Outwardly he looked healthy and strong. But in walking he had to help himself with a cane, and he advanced at a slow and heavy pace, as if he were repressing a hidden pain or making a great effort at every step. There was effort in his speech, too. His shiny cassock was mended in more than one place. He wore thick-soled boots, battered but well polished. When I arrived he was counting small notes and ranging them in bundles in a basket. "The alms," he said. "They are meager." One of the first things he told me was that he wished he knew more about American democracy. The question was not quite clear to him. He had been told that for the Americans democracy finally rests on education. But what was the basis of education, then? How could there be education without a supreme truth binding together the teacher, the pupil, and the society in which they lived? "I don't know about America," he went on. "But I do know about the kind of democracy we are supposed to have over here. It's an imposture: the lie you have to tell in order to succeed. The biggest lie of all is Christian Democracy, a contradiction in terms. At the opposite end, there are the Communists. The Communists are pursuing their own anti-Christian aim; but they do have a notion of authority. It is quite normal that they should exploit confusion in order to get Evil. You cannot say that they are lying. It is their faith itself which is imposture, the Error of our time. The other parties, however, are pitiful. For most of them, the lie they call 'democracy' is just a way of groping. Through confusion on to more confusion. In between lies this hapless country, 'a vessel without pilot in a mighty storm.’" I told him that his bitterness was surprising to me. I should have thought that a Catholic would feel rather hopeful in Italy. The Church had never, for the last eighty years, been so politically and economically strong. And the Christian Democrats might prove a useful expedient, after all. Why object to them on the grounds of logic? He had a tired smile. "Diplomacy. I know, I know. The trouble is that it is not an adequate answer. Diplomacy might be necessary in high places, but you can't give diplomatic answers to people who come to you for advice and comfort. You have to take chances, and open your heart to them. The people are distressed. They find it more and more difficult to be Christians in a society that becomes less and less Christian every day. They are the prey of economic and political anxiety. They want to know what to do now. It is only by giving them straight answers that you can retain their confidence." "And what is your answer?" I asked. "They must have told you that I am a Fascist," he said with a boyish giggle. "Of course I am not. I am a Jesuit. Moreover, the only restoration I care for is the restoration of society to Christ. But, if we want to be serious and not just cry wolf after the wolf is dead, as people are doing today, we have to recognize that Fascism, insofar as it realized that the social problem is first of all a problem of authority and that there can be no authority without Catholicism, was a step in the right direction, and a most important one at that. The trouble was that, like so many Italians, Mussolini was an amateur. He thought it possible for a political leader of our time to be a Catholic only up to a certain point. In this he was no better than so many liberal politicians. Italy is now paying for his mistake. But the fact is that, if Fascism has been defeated, it has by no means been proved wrong. We knew that the moment we became a conquered people. If I were a cardinal I would be prudent. But I am a parish priest, and what can I, in all conscience, tell people who come to me for advice, except that the principle which was beginning to give the Italian nation a true Catholic shape must not be given up? What comforts me is that the younger generation seems to be aware of this duty." All this was asserted with passion, as if it were an absolutely personal belief. But it wasn't. In fact, another Jesuit, Father Lombardi, the most popular orator in Italy after Togliatti, was saying very much the same thing, in public places as well as over the radio. He introduced himself on the radio with the words "Jesus is at the microphone. Jesus wants to speak to you. Listen to Jesus" (the cover of the volume in which his radio talks have been collected bears a reproduction of the head of Christ from Raphael's Transfiguration, with the addition of a neatly drawn microphone in the right corner). As for Father Lombardi's political message, it was quite straight. He tried to give heart to the distressed Italians by pointing out that "a newly reorganized life might be better than the one we have been forced to renounce." Italy, he said, still has the greatest possessions of all, Rome and the Pope. Italy's greatest glories have all been Christian and Catholic. The nation can be reborn in spite of the "shameful peace treaty" imposed on her by "the cowardice of the conquerors." Italy has a right to have her colonies back and also to have a new army, whose young soldiers "can again confidently sing the motherland's songs." If the Italians stick by their "two mothers, the motherland and the Church," there can be no doubt about "the final triumph." In-his final talk, the speaker was troubled by the query whether "the devil will not unleash a battle in order to prevent Italy's rebirth in Christ . . . and spill new blood over our soil." "That blood," the Father reassuringly answered himself, "if it should be spilled, will spell doom for the men who have committed the crime. And from that blood Italy will be reborn, more beautiful than ever." I told Martelli that his remarks reminded me of what Father Lombardi had been preaching. The general idea seemed to be National Catholicism, or was I wrong? "I can see the logic of it," I said, "but I don't see how your notion of authority can be made to work. If what you have in mind is straight theocracy, then allow me to say that in my opinion it hasn't got a chance. Granted that the Italians are by and large still Catholics, you must admit that their Catholicism is of such a kind that it excludes precisely the notion that the Church should become an absolute power. And you are not thinking of a new adventure in dictatorship, are you?" "You have been away a long time," he answered. "Apparently you have remained more of an optimist than I have. You still think in terms of intellectual alternatives. But, my dear friend, there are no alternatives. Would to God that theocracy, as you call it, were today an actual choice. It would mean that society had remained essentially Christian. Harmony between religion and politics would then still be the generally accepted norm, and it could always be achieved through some kind of wise adjustment. Unfortunately, we don't live in the thirteenth century. We live in a time that is the negation of any harmony. If you were a priest, you would know to what a horrible extent the moral life of the individual is constantly yielding ground under the pressure of social disorder. Christian restoration today means Christian reconquest of society. The only question is 'Where should we start from?' If by dictatorship you mean emergency power, I can only answer that the present situation is, indeed, one of dire emergency. There is no other point from which to start except an act of authority.” I left, and found myself back in the Roman streets and squares: the Roman space, so generous, so free of compulsion, rejecting nothing, asking nothing of the individual, except that he pick up a disguise and play a role, forgetting himself in it. The cast is innumerable, the stage set once and for all. There is room for the Fanatic on it, and for the Cynic. Only the real person is excluded: the heretic. Or isn't he? * A Roman aristocracy created by popes and not by kings. —Ed.

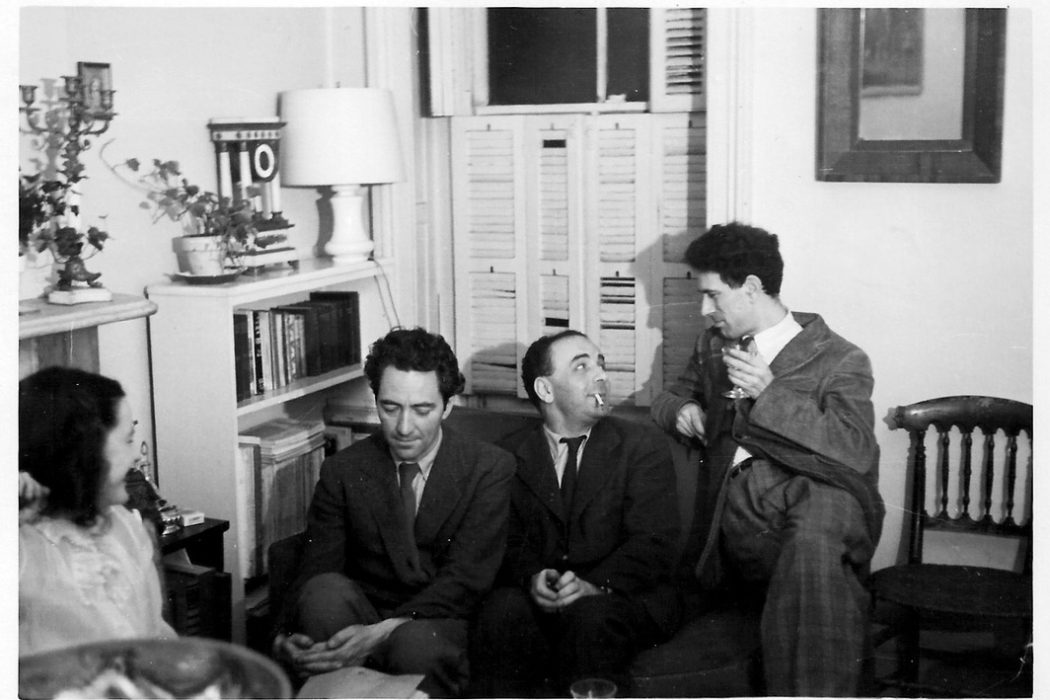

Image: Mary McCarthy, Nicolò Tucci, Nicola Chiaromonte, New York, Lionel Abel, 1947 http://www.wojciechkarpinski.com/album-chiaromonte