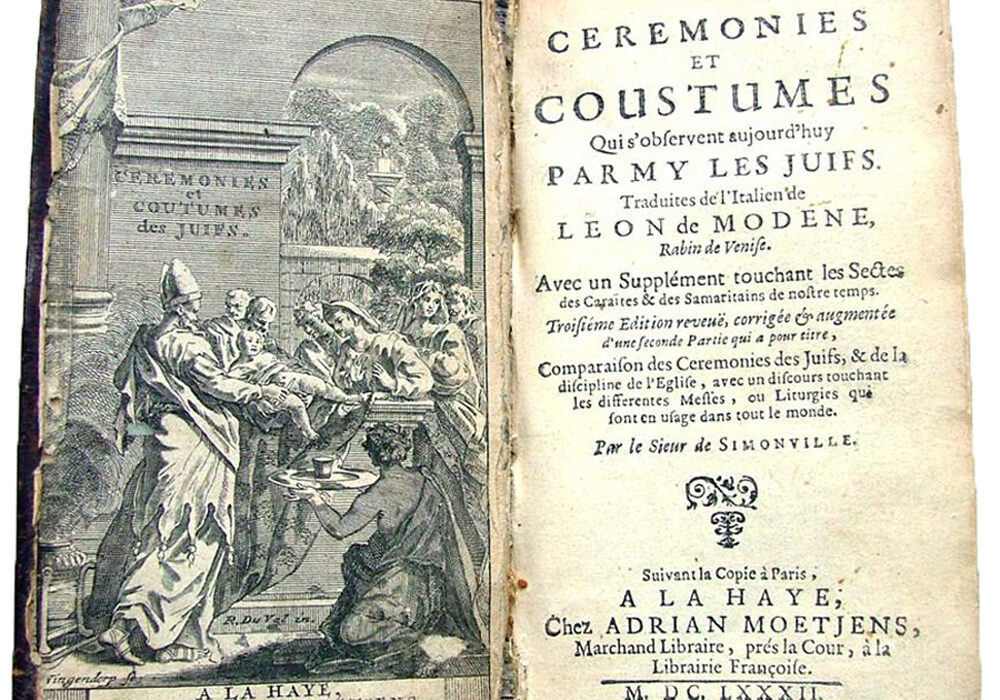

Yaacob Dweck, The Scandal of Kabbalah: Leon Modena, Jewish Mysticism, Early Modern Venice, Princeton University Press, 2011

The Scandal of Kabbalah is the first book about the origins of a culture war that began in early modern Europe and continues to this day: the debate between kabbalists and their critics on the nature of Judaism and the meaning of religious tradition. From its medieval beginnings as an esoteric form of Jewish mysticism, Kabbalah spread throughout the early modern world and became a central feature of Jewish life. Scholars have long studied the revolutionary impact of Kabbalah, but, as Yaacob Dweck argues, they have misunderstood the character and timing of opposition to it.

Drawing on a range of previously unexamined sources, Dweck tells the story of the first criticism of Kabbalah, Ari Nohem, written by Leon Modena in Venice in 1639. In this scathing indictment of Venetian Jews who had embraced Kabbalah as an authentic form of ancient esotericism, Modena proved the recent origins of Kabbalah and sought to convince his readers to return to the spiritualized rationalism of Maimonides.

The Scandal of Kabbalah examines the hallmarks of Jewish modernity displayed by Modena’s attack–a critical analysis of sacred texts, skepticism about religious truths, and self-consciousness about the past–and shows how these qualities and the later history of his polemic challenge conventional understandings of the relationship between Kabbalah and modernity. Dweck argues that Kabbalah was the subject of critical inquiry in the very period it came to dominate Jewish life rather than centuries later as most scholars have thought.

From the introduction:

“Modena’s criticism and its subsequent history constituted some of the very ruins evoked by Scholem at the outset of Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, ruins that Scholem himself recovered with such magnificent and ruthless efficiency in the construction of his own narrative. Ari Nohem and its history were profoundly inconvenient to the integrity of Scholem’s story. It undercut two of the central and contradictory claims upon which he built his scholarly edifice: the marginality of Kabbalah and its ostensible neglect as the subject of critical inquiry. Scholem was of two minds about the place of Kabbalah within Judaism: at times he insisted upon Kabbalah as a vibrant but subterranean force within Jewish history; at other times he insisted on its absolute centrality.

But he was piercingly clear about its neglect as an academic subject before he wrote his doctoral dissertation on Sefer ha-Bahir. I wish to be clear about what I am not doing: Modena was not Scholem in Baroque Venice. In one of his late pieces, Scholem perceptively pointed to Reuchlin as his intellectual ancestor. Scholem may not have been a kabbalist, as he repeatedly insisted, but like Reuchlin before him he was clearly sympathetic to Kabbalah. For all his insight, Modena lacked such sympathy.”