Salman on Salzberg, ‘Ephemeral City: Cheap Print and Urban Culture in Renaissance Venice’

Reviewed by Jeroen Salman (Utrecht University) Published on H-Italy (March, 2015) Commissioned by Maartje van Gelder.

Printable Version: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=42493

Citation: Jeroen Salman. Review of Salzberg, Rosa, Ephemeral City: Cheap Print and Urban Culture in Renaissance Venice. H-Italy, H-Net Reviews. March, 2015.

URL: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=42493

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

Read more or reply

This work on cheap print fits into a long historiographic tradition that started with such important pioneers as Robert Mandrou, Margaret Spufford, Rudolf Schenda, and Roger Chartier. Although the first monographs date back to the 1960s, the field of popular print culture has always appealed to new generations of scholars. This interest has led to multiple projects, initiatives, and publications. A recent English example is the multivolume Oxford History of Popular Print Culture, edited by Joad Raymond, of which the first volume appeared in 2011: Cheap Print in Britain and Ireland to 1660. Rosa Salzberg’s study, Ephemeral City: Cheap Print and Urban Culture in Renaissance Venice, focuses not on England, France, or Germany, which has often been the case, but on Italy. Furthermore, her choice of examining the urban setting of cheap print culture is in line with a recent trend; traditionally the preferred focus was on rural dissemination. And last but not least, this book is not only about the printed material but also about the connections of print with urban culture and public space. In this book, Salzberg reveals “how print permeated early modern European society, and what part it played in longer term transitions” (p. 4).

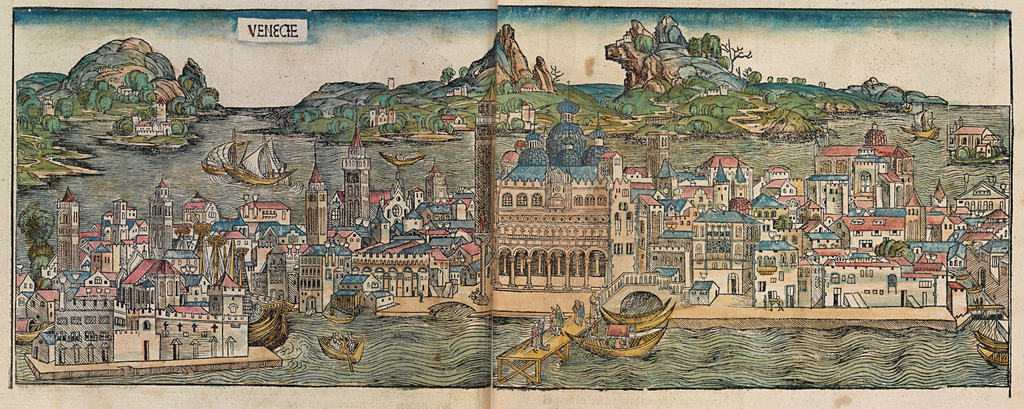

More specifically, she studies the problems and potential of sixteenth-century cheap print culture in Venice. This city is well chosen indeed; it was one of the most important centers of early modern book production. Geographically and culturally her perspective is wider, since she places Venice in a broader Italian context (such as the Italian wars). One of her crucial findings is the very fast and early manifestation of cheap print in this city and the eventual, relative freedom in which it could be produced and distributed. Only in the second half of the century do we see a growing awareness of the power of print and the fear among authorities that it would enhance popular discontent.

The different concepts that are used for cheap or popular print by scholars in the field have generated a long and fierce debate. Especially in the Italian academic context, the use of “popular print” is rejected because of the perception that it was only aimed at the lower classes. According to Salzberg, “cheap print” is neutral, because it implies accessibility and includes a wide, undefined audience. The genres that Salzberg discusses range from devotional booklets, “fogli volanti” (chapbooks), and pamphlets, to prognostications, ballads, and recipe books. With the concept “ephemeral” Salzberg refers not only to the short life of printed material but also to the fluid and dynamic infrastructure of the cheap print industry as a whole. This organic approach is appropriate since it does not isolate the phenomenon from its contemporary setting and function.

In the larger context of research on European popular print culture, the specific contribution of this book is that it zooms in on the first explorative phase of cheap print culture. Authors, printers, authorities, and audiences did not know exactly how to relate to cheap print. There were no formal and institutional regulations; no clear distinctions between oral, written, and printed culture; and no strict borders between high and low culture.

An illustrative example of this last aspect is the publication of Ariosto’s masterwork Orlando Furioso in 1516, which was followed by manifold editions, ranging from very cheap (including songs and playing cards) to extremely expensive. Furthermore, performers in piazzas also produced or influenced creative adaptations, such as sequels, subversive versions, and parodies of the poem. Through these performances, the work reached a far wider audience than we would expect of such a complex and voluminous poem. From the early sixteenth century onward, cheap print culture became one of the main forms of urban communications, as a strategy to respond to important events and as a commodity with large commercial possibilities. Salzberg illustrates these functions with various examples of religious works, printed news, and medical books.

Salzberg makes a strong link between cheap print and the dynamics of production and distribution. She demonstrates that eventually there was no significant division between the established, sedentary booksellers and the large, itinerant group of stallholders, street sellers, and ballad singers. The social classes were not strongly segregated but rather permeable, making it possible, for instance, for a stallholder to become a bookseller.

Also, professional roles were not yet strictly divided, meaning that a printer could easily combine his printing shop with peddling on the street. Publishers and printers were not always happy with street sellers—their main competitors—but still collaborated with them frequently, especially if they wanted to disseminate seditious works. In this context of regular versus irregular trade, it would have been helpful if Salzberg had provided some quantative overviews of the Venetian book industry (for example, numbers/estimate of booksellers, stallholders, streetsellers, and books produced). This would have given the reader a better perspective on the impact of both the regular and irregular trades.

It is undoubtedly justified that Salzberg pays a lot of attention to the street trade as a broad cultural phenomenon. Much more than just selling prints on the street, pedlars, performers, and ballad singers contributed to urban culture, and this was certainly not to the dislike of many citizens.

Print could be sold in shops or on the street; it could be sung or recited and it could be posted, handed out for free, or advertised. Paradoxically, cheap print was often presented and advertised with oral forms of communication. Although the “performance” of cheap print was fuelled by a commercial incentive, the audience considered these activities as a welcome form of distraction and as a public event. These street sellers had an additional function as intermediaries between the public and producers, because they could inform publishers about the balance between supply and demand.

Street trade went further than only print: sellers often combined commercial (ribbons, soap, perfume, medicine) and cultural goods (books, prints) in their pack. In fact, Salzberg did not come across large networks of pedlars who specialized in print, which is similar to the situation in the seventeenth-century Dutch Republic. This was probably due to the often ad hoc and short-term character of the urban street trade and the absence of long-term contracts based on credit.

Salzberg describes with great precision the emergence of commercial regulation and press control after the initial decades of more or less uncontrolled expansion. During periods of crisis, war, famine, the plague, and political conflicts, the circulation of cheap material raised suspicion among ecclesiastical and political authorities. Especially from the 1530s onward, when religious reformers started to use print to propagate their heterodox ideas, Venetian authorities became fully aware of the potential danger.

This resulted in a growing number of prepublication censorship laws, accompanied by indices of forbidden books. In line with this, in 1549 the Venetian Council of Ten ordered the establishment of a booksellers guild, which marginalized the position of nonmembers, foreign booksellers, and ambulant pedlars. As a result, “many producers and distributors of cheap print chose to tread a safe path and to avoid more provocative material” (p. 149). It would be interesting to compare this Venetian life cycle of cheap print with other European cities, such as London and Amsterdam, especially since recent research has revealed similar developments from relative freedom to more restrictions (see Roeland Harms, Joad Raymond, and Jeroen Salman’s edited collection Not Dead Things: The Dissemination of Popular Print in England and Wales, Italy, and the Low Countries, 1500-1900 [2013] and Salman’s Pedlars and the Popular Press: Itinerant Distribution Networks in England and the Netherlands, 1600-1850 [2014]).

It is somewhat disappointing that Salzberg did not add a comparative chapter, putting the Venetian case study in a wider Italian and European context. This book derives its value primarily from its close description of a dynamic process in one specific, but important, city. In doing so, Salzberg has produced an excellent, well-written, and informative introduction into the early modern world of cheap print culture.