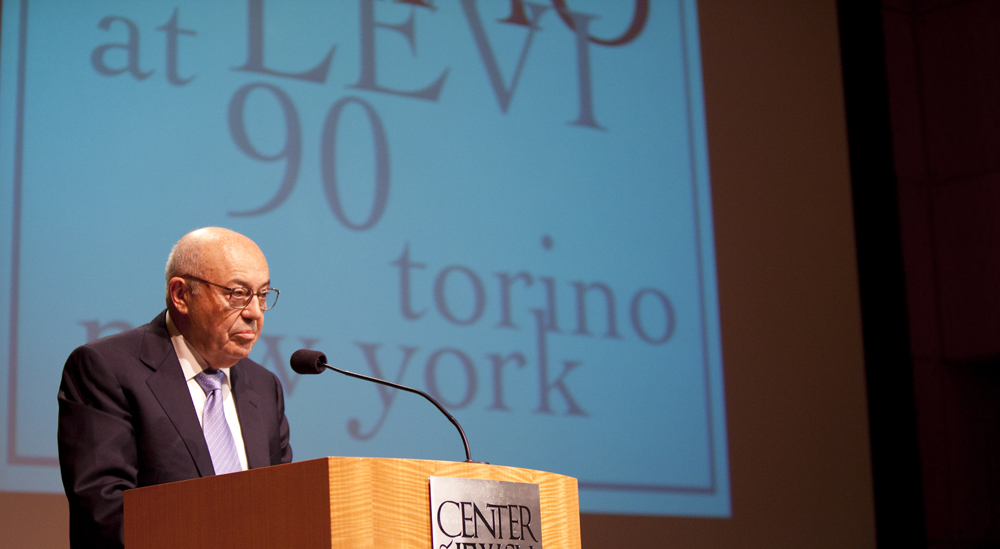

Primo Levi through the archives

An introduction to Primo Levi’s life and work realized by Cynthia Madansky for the Library of Congress National Book Festival 2016 with support from the American Initiative for Italian Culture and the Italian Embassy in Washington D.C. Archival images and footage provided by the Digital Library of the Center for Contemporary Jewish Documentation, Centro Internazionale di Studi Primo Levi, Archivio Patrizia Antonicelli, Archivio Ebraico Terracini, Leo Levi Family, Archivio Serafino, Fabrizio Salmoni, La Stampa, Fondazione Fossoli, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and RAI Teche. Music: Luigi Dallapiccola’s Quaderno Musicale di Annalibera recorded by Matthew Laurence Edwards, San Francisco 1991. Qaddish, Aldo Perez recorded by Leo Levi in 1954 and published in the collection: Musiche della tradizione ebraica in Piemonte curated by Franco Segre and produced by the Archivio Ebraico Terracini.

The publication of Primo Levi’s Complete Works welcomes readers to a maze of different worlds, cultures, and historical references. Italy and Italian history, Piedmont and Piedmontese Jewry, science, literature, language, and fascism ideology and a form of social interaction and individual response.

Archival sources to learn more about Primo Levi’s worlds.

- Centro Internazionale di Studi Primo Levi

- Centro di Documentazione Ebraica Contemporanea

- Istituto Piermontese per la Storia della Resistenza/Archivio Serafino

- Polo del Novecento Torino

- Archivi Ebraici del Piemonte

- Archivio Ebraico Terracini

- Fondazione Fossoli

- Archivio Franco Antonicelli

- The Persecution of the Jews in Italy

Primo Levi: A Library of Quotations

It is true that technology has scandalously yielded to the orders of politicians, but this is not the main mistake of the technicians. Only those who are intoxicated by the news can fail to realize that the gigantic transformations underway in today’s world, good or bad, originated in laboratories, and not in parliaments: new crops and new weapons, new diseases and new therapies, new sources of energy and new contaminations. In my opinion, the greatest fault of the technicians (for scientists, the matter is different) was not their capitulation to power, but having underestimated their own strength, and the extent of the transformations they unleashed: this is a Vice of Form. I do not think it is irreversible, I hope that all the technicians in the world understand that the future depends on their return to conscience: I am sure that a restoration of the balance is possible without the need of new discoveries and, above all, without massacres. 1976

I think the discourse on work is important. The reasons that moved me to write about it are not so clear to me. I like to say that I wanted to fill an ecological niche: literature is full of duchesses, prostitutes, adventurers, why not also include some of us, transmuters of matter? And then the 1968 discourse on work seemed very abstract to me. I think of the parlor trade unionists, for whom the world is made up of slaves on the assembly line and evil masters. In reality, the world is more articulate: there is, between those extremes, a place in which work is neither punitive nor alienating. Like the work I did for many years, in a small factory. Those years were not lost. In my work I found a Conradian image of life, the importance and constructive work of those who labor in view of a result. I saw the acceptance of responsibility as opposed to the rejection of responsibility: a way of becoming an adult.

I stopped being a survivor since I started to write, but I continue to be one. Next week I will meet with Nelo Risi and Ludovico Belgioioso to organize an Italian memorial at Auschwitz. But in the past thirty-five years I have accumulated different experiences, and it is useful to talk about them. It was noted that human dignity is the continuity between If This is a Man and The Wrench. My next book will be a reflection on the ambiguity of the prisoner’s condition, on the difficulty of judging it. This is a vast problem, because the typical prisoner in the lager, is dead. The survivor is such because he enjoyed some privileges: I was a chemist. It is difficult to judge the limits of compromise. There is a whole ladder, which begins where you agree to survive, and thus agree to work for the enemy.

Open Anthology

Timeline in Context

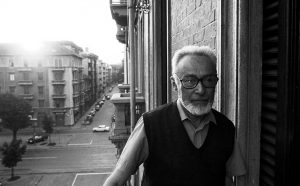

Primo Levi’s life span—1919-1987—extended from the end of World War I, to the years leading to the fall of the Berlin Wall. All of his formative experiences — growing up in Fascist Italy in a middle class Jewish family, the ignominy of the Racial Laws, participating to the Resistance, his study of chemistry, his love for the Classics and mountaineering, his arrest and deportation to Auschwitz, his writing, — contributed to distill one of the most acute, intransigent and far reaching reflections on the human condition. As a scientist, witness, writer of memoirs, fiction, poetry and essays and as a public intellectual, Levi’s attention focused on the relationship between the powerful and the powerless, the corruptibility of the individual and collective moral fiber. Primo Michele Levi was born in Turin, in the house he inhabited his whole life, on July 31, 1919. His father, Cesare, graduated in electrical engineering in 1901, and was employed by Ganz, a manufacturing company based in Budapest. Levi recalled his father as an outgoing person, someone modern for his times and a lover of good living and good reading who paid scarce attention to family affairs. In 1918 he married Ester Luzzati, known as Rina, an avid reader and amateur pianist who spoke impeccable French. Levi’s ancestors were Piedmontese Jews who had come from Spain and Provence whose language, customs, and lifestyles are described in The Periodic Table. His paternal grandfather was a civil engineer who lived in Bene Vagienna in the Province of Cuneo, where he owned a house and a little farm. His maternal grandfather was a cloth merchant. Primo’s sister, Anna Maria, to whom he had a strong bond throughout his life, was born in 1921.

In 1938, when Mussolini’s Racial Laws deprived Italian Jews of civil rights, Levi was forced to work in a semi-clandestine condition. In 1944, he joined the resistance movement with a group of inexperienced friends. Arrested almost immediately by the Fascist police, he was deported to Auschwitz. He survived and returned to Italy at the end of 1945. His account of life, work, and death in the camp, If This Is a Man, translated into 45 languages, has become a fundamental reference for scholars of 20th-century totalitarianism, human nature, and power.

In 1947 he married Lucia Morpurgo from who he had two children, Lisa (1948) and Renzo (1957). He died in 1987.

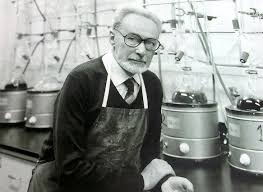

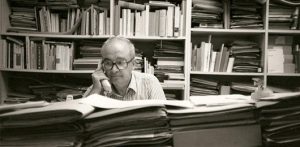

Levi worked for most of his life as a factory chemist. Writing was his “other trade”. His book The Periodic Table, which brings together his two worlds, was published in English in 1984 and gave him international acclaim through the endorsement of Saul Bellow and, later, Philip Roth. His experiences in the industrial setting of Turin, where he witnessed the intersection of science and labor, greatly influenced his writing and his perspective on the human condition. Through short stories, novels, memoirs, and an intense public activity on the radio and the press, Levi focused on the fragility of democratic societies, state violence, economic injustice, the nature of labor, the destruction of the planet, the beauty of science, and the perils of the unregulated pursuit of technological advancement.

In his final book, The Drowned and the Saved, Levi articulated the concept of “grey zone,” which had a far-reaching influence on contemporary political and ethical thought. Having witnessed the persistence of violence, warfare, and a culture of consumption, Levi re-examined the questions he had dealt with in forty years of writing: What are the structures of an authoritarian system? What are the tools to degrade and simplify conscience and knowledge? What is the relationship between the oppressors and the oppressed? What dynamics surround and enable it? Who is a monster? Is rebellion possible? Would all human beings, under certain conditions, exercise extreme violence against others?

1919

Primo Levi’s father, Cesare, obtained a degree in electrical engineering in 1901, and was employed by Ganz, a manufacturing company based in Budapest. His mother, Ester Luzzati, known as Rina, was an avid reader and amateur pianist who spoke impeccable French. Levi’s ancestors were Piedmontese Jews who had come from Spain and Provence.

1919-1922

1919 The Fascist Movement is founded.

1922 March on Rome. Mussolini is nominated Prime Minister of the Kingdom.

1924 Murder of the opposition leader, Giacomo Matteotti.

1925-26 Abolition of civil liberties and democratic institutions with the “Leggi Fascistissime”.

1925-1935

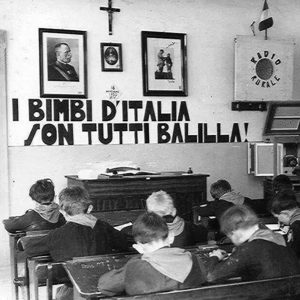

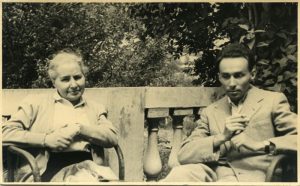

By the time Levi entered elementary school Italy and its educational system were run by a full-fledged dictatorship. In 1934, Levi enrolled in the prestigious Ginnasio-Liceo D’Azeglio, famous for its illustrious teachers and students, many of whom were opponents of Fascism (Augusto Monti, Franco Antonicelli, Umberto Cosmo, Zino Zini, Norberto Bobbio, and many others). The D’Azeglio school had by then been “purged” and came across as politically neutral. Levi was a timid and hard-working student. He was attracted to chemistry and biology, more than to history and literature. During his third year, Cesare Pavese was his teacher. Here, Levi made friendships that would last for life. He went on vacation in Torre Pellice, Bardonecchia, and Cogne and discovered his love for mountaineering.

1929-1935

1929-1931 Following the Lateran Pacts, Catholicism becomes the State religion. The Pacts are followed by the Falco Law. Jewish communities are centralized under government control. It becomes mandatory to be registered as a member of the Jewish community or to abjure.

1935-36 Italian invasion of Ethiopia. For the first time in the 20th century, lethal gas is used against civilians. The League of Nations, of which Ethiopia is a member, fails to enforce sanctions against Italy. The invasion is saluted with enthusiasm by the Vatican and by the Italian population. The victory in Ethiopia strengthens Mussolini’s rule.

1937-38 Italy institutes the first set of Race Laws to regulate relations between Italians and Ethiopians.

1937

Primo Levi graduated from secondary school and enrolled as chemistry major at the University of Turin’s School of Sciences.

School under Fascism. From: Interview with T. Regge, 1980

“For me, too, the university experience was liberating. I still remember Professor Ponzio’s first chemistry lesson, from which I got clear, precise, verifiable information, without useless words, expressed in a language that I liked enormously, also from a literary point of view: a definite language, essential. And then the laboratory: every year he included a laboratory session. We spent five hours there; it was a big commitment. An extraordinary experience. In the first place because you worked with your hands, literally, and it was the first time this had happened to me, never mind if you scalded your hands or cut them. It was a return to the origins. The hand is a noble organ, but school, all taken up with the brain, had neglected it. And besides, the laboratory was collegial, a center pf socialization where one really made friends. As a matter of fact, I remained friends with all my laboratory colleagues […]. Making mistakes together is a fundamental experience. One participated fully in the mutual victories and defeats. Quantitative analysis, for example, in which they gave you a bit of powder and were supposed to tell what was in it: not to realize that there was bismuth or to find chrome that wasn’t there were adventures. We gave each other advice, we sympathized with each other. It was also a school of patience, of objectivity, of ingenuity, because the methods they suggested to you to perform an analysis could be improved.”

1938

At the time of the promulgation of the Racial Laws, Primo Levi had completed the first half of his course. The Law provided that students who had passes the second year be allowed to finish their studies.

He associates with groups of anti-Fascist students, both Jewish and non-Jewish. He read Thomas Mann, Aldous Huxley, Laurence Sterne, Franz Werfel, Charles Darwin, and Lev Tolstoy.

1938

The Fascist government promulgates the Racial Laws, stripping Italian Jews of civil rights and expelling from the country Jews who do not have Italian citizenship. Among many repressive measures, the laws prevent Jews from attending schools, remove them from public office, limite and eventually forbid ownership of assets.

Discrimination and free will. Levi, The Search for Roots, 2003 and Interview by G. De Rienzo, 1975

“I have read a great deal because I came from a family for whom reading was an innocent and traditional vice, a gratifying habit, a mental exercise, an obligatory and compulsive way of killing time, and a sort of fairy wand bestowing wisdom. My father was always reading three books simultaneously; he read ‘when he sat at home, when he walked by the way, when he lay down and when he got up’ (Deut. 6.7); he ordered from his tailor jackets with large and deep pockets each one of which could hold a book. He had two brothers just as interested in indiscriminate reading”.

“The racial laws were a God-send for me, but for others too – the reduction to absurdity of the stupidity of Fascism. By then, the criminal face of Fascism had been forgotten – that of the Matteotti assassination, to make myself clear. What remained to be seen was its silly face […]. In my family Fascism was accepted with some impatience. My father had joined the party unwillingly, yet he put on the black shirt. And I was a balilla and then an avanguardista [a boy (8-14 years old) and then a youth in Fascist paramilitary organizations]. I could very well say that the racial laws gave me my free will back, as it did to others.”

1940-42

Levi graduated cum laude from Turin University in 1941. His diploma bears the annotation: “of the Jewish race.”

Under pressure because of his family financial straits, he began looking for work, while his father was dying of cancer. He eventually found a job working off the books in an asbestos mine near Turin. He was assigned to the chemistry laboratory to isolate nickel, an element that occurs in in very small quantities in scrap materials. (See “Nickel,” a chapter in The Periodic Table). In 1942 he found a better job in Milan at a Swiss pharmaceutical company researching a new drug for diabetes. When Levi moved to Milan, he took only a few things he thought were indispensable – “My bicycle, Rabelais, the Macaroneae, Moby Dick translated by Pavese, a few other books, my pickax, climbing rope, logarithmic ruler and recorder.” (Levi, The Periodic Table). He socialized with a group of friends from Turin.

1939-1944

1939 World War II breaks out.

1940 In June, Italy enters World War II.

1941 With German military support, Italy wages war against France, Yugoslavia and Greece.

1941 In December the United States enter World War II.

1942 In November, the Allies land in North Africa. In December the Russians defend Stalingrad victoriously.

1943 In July, the King of Italy deposes and arrests Mussolini.

On September 8 the government of Pietro Badoglio [Italian marshal who took charge of the country under Allied control] signs the armistice with the Allies. German armed forces occupy northern and central Italy re-establishing Mussolini’s rule. The Italian Social Republic issues an order of arrest for all Jews who have remained in the country, estimated to be between 30,000 and 32,000.

Resistance

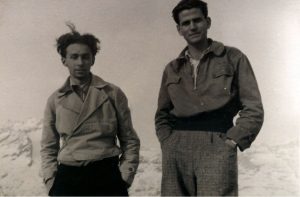

“My period as a partisan in the Valle d’Aosta was undoubtedly the most muddled in my career and I don’t like to talk about it on my own. It is a story of well-intentioned but stupid young people and it’s an episode that could very well be put on the shelf among other forgotten things. The allusions I made to this period in The Periodic Table are already enough if not too much.”

1943-1944

After the armistice, Levi and his friends made contact with several militant anti-fascists and rapidly become fully politicized.

After the armistice, Levi and his friends made contact with several militant anti-fascists and rapidly become fully politicized.

They first joined the clandestine Action Party [Partito d’Azione] and then a partisan band operating in the Valle d’Aosta. They were betrayed and arrested soon after.

Identified as a Jews, Levi was transported to the concentration camp at Fossoli di Carpi near Modena.

1944

In February 1944, the Italians passed the rule of the camp of Fossoli to the Germans maintaining some administrative duties. Levi and the other prisoners, including the elderly, women and children, were loaded on a train destined to Auschwitz. The trip lasted five days. Upon their arrival the men were separated from the women and children and sent to barrack number 30.

Fossoli and Auschwitz, Interview by F. Camon, 1989 and Interview by A. Bravo & F. Cereja, 1983, 2001

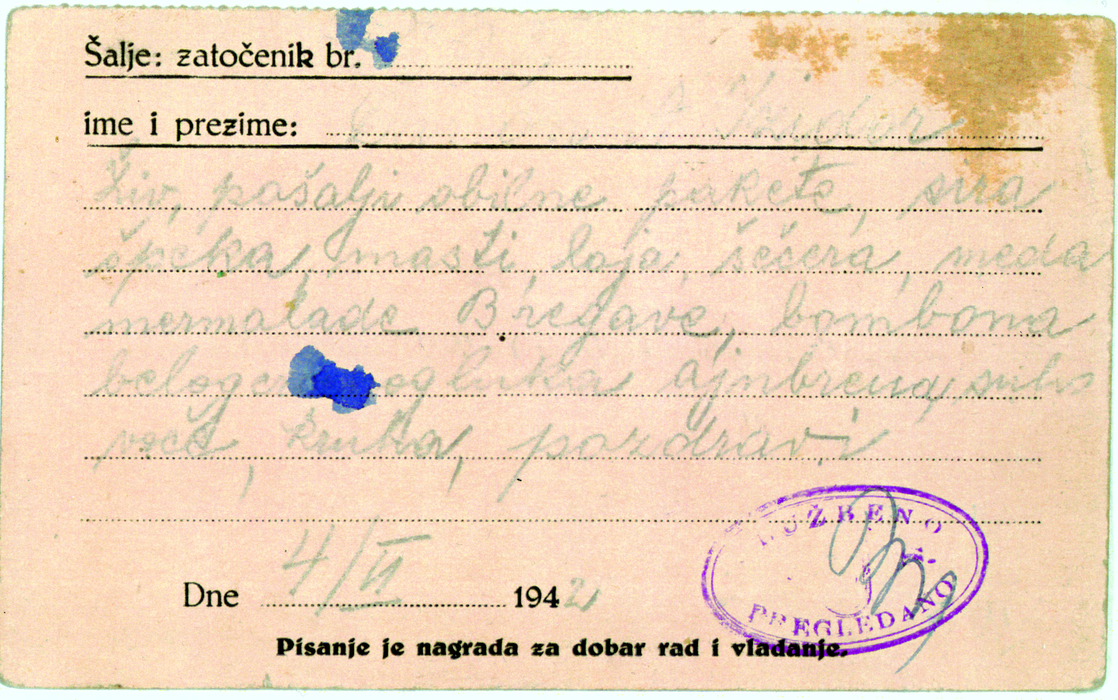

“We were being held by the Fascists, who did not treat us badly. They let us write letters, let us receive packages, and swore to us on their ‘Fascist faith’ that they’d keep us there till the end of the war.”

“The first days were terrible — for everyone. There is a ‘shock’, a trauma connected with entrance into a concentration camp which can last five, ten, twenty days. Nearly all the people who died, died during this first phase. Our way of life had changed totally in the space of a few days, especially in the case of us western Jews. Polish and Russian Jews had done some hard training for the Auschwitz experience in the ghettos beforehand, and the shock for them was less severe. For us, the Italian, French and Dutch Jews, it was as if we had been plucked straight from our houses to a concentration camp. But I could feel, along with fear and hunger and exhaustion, an extremely intense need to understand the world around me. To begin with, the language. I know a little German, but I felt I had to know a lot more. I went so far as to take private lessons, paid for with part of my bread ration. I didn’t know that I was learning a really vulgar kind of German”.

“The contact I had with Eastern Judaism was traumatic and negative. We were rejected, as Sephardi or in any case as Italian Jews, because we didn’t speak Yiddish, we were doubly foreign, both for the Germans of course because we were Jews and for the other Jews from the East because we were not part of their world, they had not the slightest idea that there was any other kind of Judaism…. As Italian Jews we felt especially defenseless. Along with the Greeks we were the lowest of the low, and in some way we were worse off than the Greeks because they were at least used to discrimination, there was a long history of anti-Semitism in Salonika [Thessaloniki], and many of them were old hands, had developed hard shells through their contacts with other Greeks. But the Italians, so used to being treated as equals of all other Italians, had no shield, we were as naked as eggs without shells.”

Auschwitz

In June, Levi was assigned to work as a manual laborer with a team of masons who had to build a wall. He met a mason from Fossano named Lorenzo Perrone, who worked for an Italian company with a branch at Auschwitz and who could move about with moderate freedom. Perrone took Levi under his wing, securing for him a bowl of soup whenever he could. Levi was then transferred to a laboratory because of his background as a chemist. Levi managed to stay healthy almost as long as he was in the camp. He contracted scarlet fever at the exact moment when the Germans were evacuating the camp under the onslaught of the advancing Russians, abandoning the sick to their fate.

The other prisoners were moved to Buchenwald and Mauthausen. Almost all of them died. On the “terrible and decisive” night when the Germans were wavering between killing the prisoners and taking flight, Levi remembered ending up by accident with a book in his hands, one that would have some meaning for him in his activities as a writer: Roger Vercel’s Remorques (The book narrates the adventures of a salvage tugboat on the high seas and of its captain, Renaud). Levi thought that this was a very relevant topic, and at the same time one “that was exploited very little […]. It was a human adventure in the world of technology” (The Search for Roots: A Personal Anthology).

Return to Italy

Following liberation, Levi lived in a Soviet transit camp for a few months in Katowice, where he worked as a nurse. In June, 1945 he began his journey home through a devastated Europe wandering for nine months at the mercy of random transports. Levi and his companions traveled first into Byelorussia and then finally home to Italy after crossing Hungary, the Ukraine, Romania, and Austria.

Levi wrote of this experience in The Truce. “Family, home, factory are good things in themselves, but they deprived me of something that I still miss: adventure. Destiny decided that I should find adventure in the awful mess of a Europe swept by war.” (Interview by Roth in Belpoliti & Gordon, 2001)

1945 On August 6 and 9, the US Air Force drops atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki

1946 Called to the polls to chose between republic and monarchy, the Italian people chose the republic. The government lead by Palmiro Togliatti extends the amnesty to all functionaries implicated with fascist and war crimes.

1945-1946 The first Nuremberg Trials are celebrated against Nazis responsible for the extermination camps and war crimes. The Allies decide not to go forward with the planned trial for Italians responsible for the crimes of the dictatorship.

Hiroshima

Nothing remains of the Hiroshima schoolgirl,

A shadow printed on a wall by the light of a thousand suns,

Victim sacrificed on the altar of fear.

Powerful of the earth, masters of new poisons,

Sad secret guardians of final thunder,

The torments heaven sends us are enough.

Before your finger presses down, stop and consider.

(from: Primo Levi, The Child-girl of Pompei)

Se questo è un uomo, the first edition

In 1946-47 amidst difficulties, Levi returned to civilian life beginning to come to terms with his own experience and the hardship of post-war Italy. He found work at the Duco-Montecatini paint factory in Avigliana near Turin. Haunted by his recent memories and the need to recollect them, he wrote If This Is a Man.

He became engaged to Lucia Morpurgo.

Rejected by Einaudi, If This Is a Man was published, in 1947, by Franco Antonicelli’s Edizioni De Silva. The last page had a brief presentation, probably by Antonicelli himself: “This book uncovers a new author. Levi composed his narrative with the simplicity of someone who has balanced his memories according to the trials he has gone through. Yet, his act of witnessing succeeds in being the act a human being and of a literary person at the same time. There is no book in the world about these same tragic experiences that has such artistic value as this book that is being published by De Silva.”

Siva and Einaudi

If This Is a Man and Italo Calvino’s first novel, The Path to the Nest of Spiders are reviewed together. This established a camaraderie and friendship between the two authors that lasted a lifetime.

In 1947, Levi married Lucia Morpurgo and shortly after accepted a job as laboratory chemist at Siva, a small paint factory located between Turin and the nearby suburb of Settimo Torinese. Primo’s daughter, Lisa Lorenza was born in 1948.

In the early 1950’s, Levi began to work with Edizioni Scientifiche Einaudi, a branch of the Einaudi publishing house. Levi did translations and text revisions. He read drafts of manuscripts and gave editorial opinions. His collaboration continued until 1957, when Boringhieri started a publishing house under his own name. In July, 1952 Boringhieri’s editorial board proposed that Einaudi publish a new edition of If This Is a Man but the idea stalled. In 1955, Levi sought again to interest Einaudi in republishing the book. An exhibition on the deportation held at Palazzo Madama in Turin, had raised great interest among young people. This time he found a receptive listener in Luciano Foà, then Einaudi’s general manager. In 1955 Levi signed a contract for the new edition of If This Is a Man. It was to appear in the moderately-priced series called Piccola Biblioteca Scientifico-letteraria. Its publication was put off until 1958.

La Tregua

In 1957, Levi’s second child, Renzo, was born. Beginning that year, Levi committed himself to writing the story of his return, which became The Truce. He wrote one chapter a month, first working from the notes he made at the time of his homecoming. He had written the first two chapters some time in 1947 and 1948, almost as a continuation of his writing of If This is a Man. It was Franco Antonicelli and Alessandro Galante Garrone, who encouraged him to put in writing the stories he used to tell his friends.

Levi wrote methodically in the evenings, on the weekends, and on vacations. He did not take one hour of work time away from his job. His life was neatly divided into three parts – his family, the factory, and his writing. He took many business trips to Germany and England.

In 1958 the new expanded edition of If This is a Man came out in the Einaudi non-fiction series with a blurb on the jacket by Bruno Munari. The first printing of 2000 copies was soon followed by a reprint. In 1959 the book was published in England and the United States by The Orion Press and met with some modest success. In 1961 the French and German translations were published, but Levi complained about the poor quality of the French translation.

The Sixties, Science and War

1955 The Vietnam War begins.

1956 Soviet troops crush the uprising in Hungary. The Suez crisis begins.

1960 Italian and German court authorities collect Primo Levi’s testimony on his arrest and deportation.

1961 The Eichmann Trial is held in Jerusalem.

1963-1966 The Treblinka trials, the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trials and the Sobibor Trials are held in Nuremberg.

1965 Martin Luther King Jr. rallies to register voters in the South.

1967 The six-Day War erupts between Israel and a coalition formed by Egypt, Jordan and Syria.

1968 Primo Levi visits Israel.

1968 Student movement’s uprising.

1969 Bomb explosions at Piazza Fontana in Milan and at the FIAT pavilion in Turin mark the beginning of a decade of terrorism in Italy.

1970 – Alexander Solzhenitsyn receives the Nobel Prize.

1971 Greenpeace is founded in opposition to US nuclear testing in Alaska.

While writing The Truce, Levi began writing short stories which were later published as Storie naturali. He tried to test the reactions of his readers by publishing them in various periodicals and newspapers.

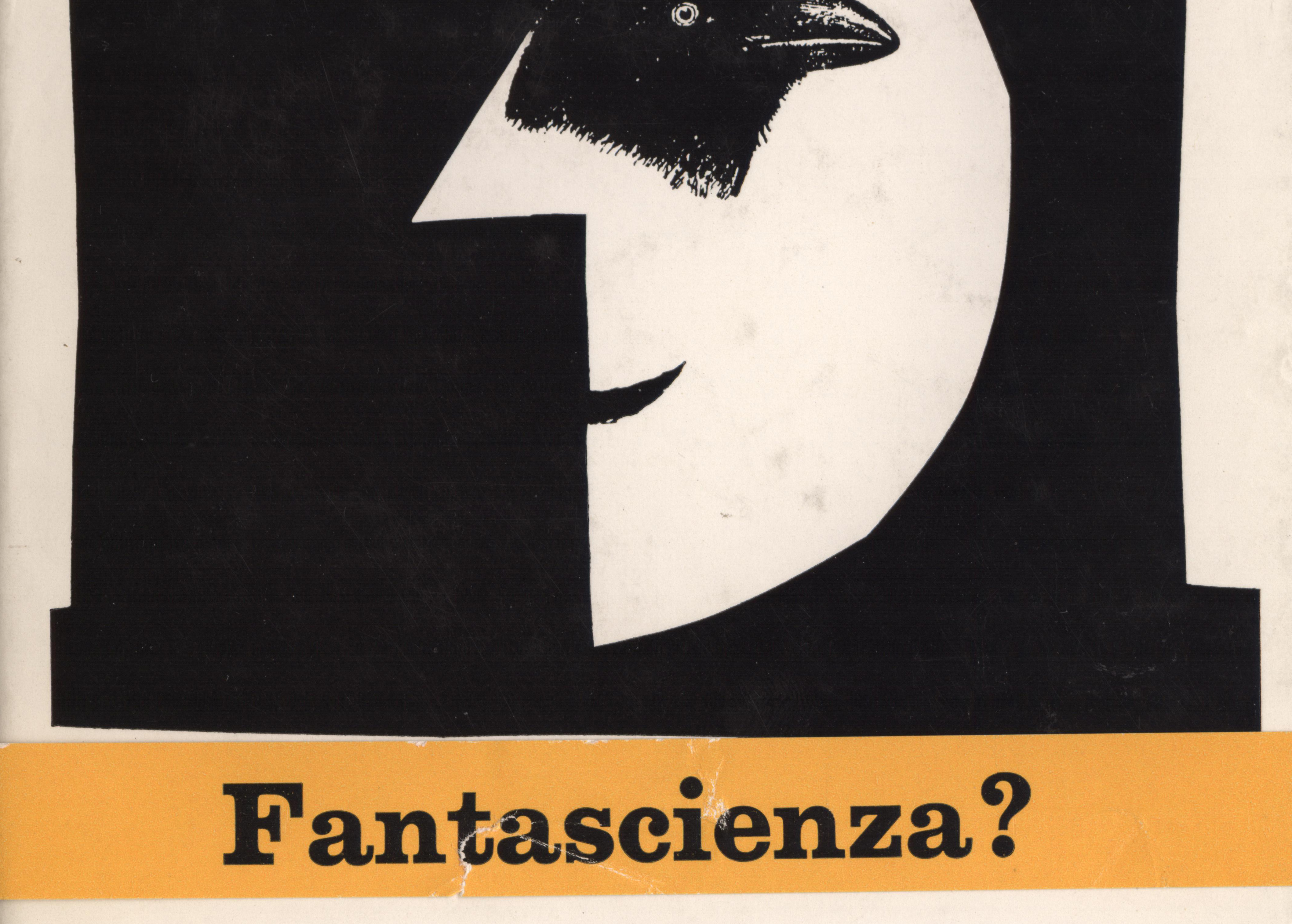

Science Fiction. Interview by W. Barberis, 1972

“When this function of mine [as witness to important historical events] ran out, I noticed that I couldn’t insist on the autobiographical register and along with this that I was too distinctively marked to be able to slide into orthodox science fiction. So, it seemed to me that a certain type of science fiction could satisfy the desire to express myself that I was still feeling and could be adapted as a kind of modern allegory. In any case, most of my stories in Storie Naturali were written before the publication of The Truce.”

Correspondence with Italo Calvino

Levi submitted several stories to Italo Calvino, who wrote his comments about them in a letter dated November 22, 1961:

“I finally read your stories. Those science-fiction ones, or, better, biological-fantasy ones, always attract me. Your fantastic mechanism that takes off from a genetic-scientific piece of data has a power of intellectual and even poetic evocation, just like the genetic and morphological meanderings of Jean Rostand. Your sense of humor and your aplomb save you very well from the danger that someone usually runs into who uses the shapes of literature for intellectual experiments of this type. Certain of your discoveries are of the first order, like that of the Assyriologist who deciphers the mosaic of the trichinosis worms. The evocation of the origin of the centaurs [the story entitled ‘Quaestio de Centauris’, published later] has its poetic force, a plausibility that imposes itself on us. (And, really, one would say that writing about centaurs is impossible today, but you have managed to avoid an Anatole-Francian-Walt-Disneyesque pastiche.) […] “You move in a dimension of intelligent meandering along the borderlines of a scientific-ethical-cultural panorama that should be that of the Europe in which we are living. Maybe I like your stories mostly because they presume that there is a common civilization that is noticeably different than that presumed by so much of Italian literature.”

Primo Levi on the Radio

In 1962, a Canadian radio station produced a radio play from If This is a Man, which Levi appreciated greatly.

“Never, perhaps, had I received such a welcome gift. Not only had they done such an excellent job, but for me it was a real revelation. The authors of the script, far off in time and space, and whose experience was very different from my own, had brought out of the book everything I had enclosed within it, and something more. It was a spoken meditation, of high technical and dramatic quality and at the same time punctiliously faithful to the reality that had been.” (Levi, 1966)

Levi offered RAI, the national broadcasting company an Italian version of the radio play, different from the Canadian one.

The Campiello Prize

In April, Einaudi published The Truce in the series entitled “I coralli”. The short text on the inside jacket was written by Italo Calvino. The jacket featured a Marc Chagall drawing of a man who seemed to take off in flight over a house. The critics received the book favorably, recognizing the narrative cunning of an author who defined himself a “writer by accident” but who was “savvy enough to free himself from the mere techniques of memoir writing”. Among the reviewers were Franco Antonicelli for La Stampa and Paolo Milano for L’Espresso. In the same year, The Truce was awarded the prestigious Campiello Prize. In interviews Levi spoke about his ambitions for the future.

Science and Literature. Interview by P. Paoletti, 1963

Storie Naturali

In 1964, Levi wrote several stories with a technological background, working on ideas that come to him in his work, in his laboratory, and in the factory. These were published in the newspaper Il Giorno and elsewhere.

In 1965, Levi returned to Auschwitz for a memorial ceremony.

“The return was less dramatic than it might have seemed. There was too much hustle-and-bustle, little reflection, everything put right in order, and a lot of official speeches.” (Levi, from a 1984 film interview)

In 1966, Levi collected his stories into a book entitled Storie naturali under the pen name Damiano Malabaila. He explained why he took these precautions in an editorial blurb on the inside jacket that made it easy for readers to identify Levi as the author. He had written these stories over the years, beginning in the 1950s. Some had been published in newspapers. The critics’ reception was tepid. Some of the stories were adapted for theater and TV.

Science fiction and Vizio di forma

During the ’70s, after the publication of Flaw of Form and coinciding with the growing debate over so-called “sociological” science fiction, Levi regards the genre less hesitantly, declaring himself extraneous to the “grand fictional inventions” and naming Voltaire, Swift, Wells, and Huxley among his models. […]

“We are children of that Europe where Auschwitz is: we live in the century in which science has been bent, and gave birth to racial laws and gas chambers. Who can be sure of being immune to the infection?” These stories were composed in the first half of the 1960s and communicate the consumeristic euphoria and the technological optimism of the Italian “economic miracle”.

Simpson’s machines evoke scientific and technological developments which were much discussed during the 1960s and with which Levi was familiar. The Versifier and the Torec are offspring of the cybernetic era that was inaugurated in Italy during the second half of the 1950s and continued throughout the following decade: from the experience of Leonardo Sinisgalli’s journal Civiltà delle macchine to Silvio Ceccato’s Adamo II, the “machine that thinks;” from the Calcolatrice Elettronica Pisana and Olivetti’s electronic calculator to Eduardo Caianiello’s studies in Naples on neuroanatomy, cybernetics, and theoretical physics. (Francesco Cassata, Science Fiction? Lezione Primo Levi, Einaudi 2016)

The sleep of reason

“I have written about 20 stories and I don’t know if I will write any others. For the most part, I jotted them down quickly, trying to give narrative shape to a little dot of intuition, trying to tell the story in other terms (if they are symbolic, they are symbolic unconsciously) of an intuition that is not very rare nowadays – the perception of an unweaving of the world in which we are living, of a little or a big crack, of a ‘structural defect’ that makes this or that feature of our civilization or of our moral universe vain… In the act of writing these stories I feel a vague sense of guilt, like the guilt of somebody who is committing some petty misdemeanor on purpose. I entered the world of writing, unthinkably, with two books on concentration camps. It is not up to me to judge their worth, but they doubtlessly were serious books dedicated to a serious public. To offer this public a volume of joke-stories, of moral traps – that may very well be amusing but are distancing, cold – isn’t this business fraud, as if I were selling wine in olive-oil bottles? These are the questions I asked myself in the act of writing and publishing these ‘natural histories.’ And so, I would not publish them if I had not noticed (not immediately, to tell the truth) that a continuity – a bridge – existed between the Lager and these inventions. The Lager, for me, was the biggest of the ‘defects’ – of the distortions – that I had been talking about before, the most threatening of the monsters generated by sleep of reason.”

La chiave a stella

In 1971, Levi collected a second series of stories entitled Vizio di forma, published this time under his own name.

In 1972-73, he took several business trips to the Soviet Union:

“I was in Togliattigrad [city housing a Soviet auto plant being built with FIAT, named after the Italian Communist Party head] and I noticed the esteem with which the Soviets treated our skilled workers. This phenomenon made me curious. Those men sat in the cafeteria with me, elbow to elbow. They represented an enormous technical and human patrimony, but they were destined to remain anonymous because nobody has ever written about them… Maybe The Wrench originated right there in Togliattigrad. It is there that the story is set eventhough the city is never mentioned.”

Labor

In the late 1960s labor struggles unhinge Italian economy and political life. Italian workers are paid among the lowest salaries in Europe while facing rising cost of life and social instability. In 1970, after violent confrontations and negotiation the government issue the Statuto dei lavoratori. Nevertheless, tensions continue. In Turin throughout the 1970s the scandal of political profiling conducted by Fiat and government officials erupts violently. One of Levi’s closest friends, the lawyer Bianca Guidetti Serra, argues the case on behalf of the workers.

In the late 1960s labor struggles unhinge Italian economy and political life. Italian workers are paid among the lowest salaries in Europe while facing rising cost of life and social instability. In 1970, after violent confrontations and negotiation the government issue the Statuto dei lavoratori. Nevertheless, tensions continue. In Turin throughout the 1970s the scandal of political profiling conducted by Fiat and government officials erupts violently. One of Levi’s closest friends, the lawyer Bianca Guidetti Serra, argues the case on behalf of the workers.

The Seventies

1971 Primo Levi testifies in front of German authorities in the trial against Friedrich Bosshammer, head of the Gestapo’s Anti-Jewish agency in Italy.

1972 Eleven Israeli athletes are killed in Munich during the Olympics by the Palestinian group Black September.

1975 Israel and Egypt sign the Sinai Accord. The Vietnam War ends.

1977 The president of Egypt, Anwar Sadat visits Israel.

1978 The Camp David Accords are signed by Menachem Begin of Israel and Anwar Sadat of Egypt.

1978 The Italian politician Aldo Moro is kidnapped and killed by the Red Brigades.

1980 In Bologna a bomb destroys the railway station, killing 85 and wounding more than 200.

1980 Anwar Sadat is assassinated by an Islamic extremist group.

Il sistema periodico and La chiave a stella

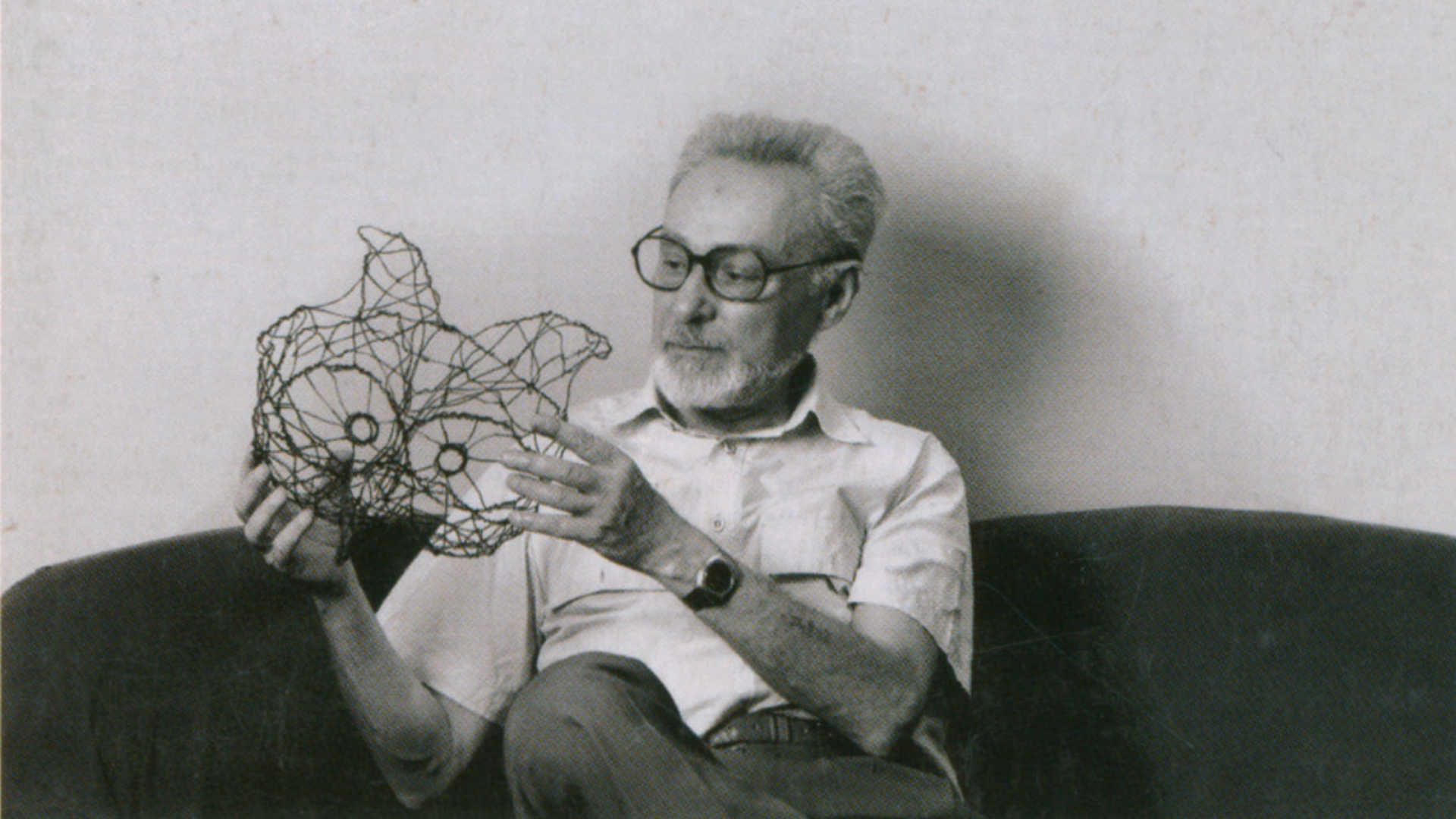

In 1975, Einaudi published The Periodic Table, an autobiography in twenty-one episodes, each one inspired by an element of Mendeleev’s table of elements.

Levi decided to retire and leave the management of Siva, but remained as a consultant for the next two years. The Wrench, published in 1978, was Levi’s first book as a full-time writer. It is the story of a mechanical rigger from Piedmont, who travels the world building pylons, bridges, and oilrigs. “While writing the novel, I felt the need to give substance to a controversy among the deaf in relation to literary people, who often – differently from technicians – feel irresponsible for their ‘products.’ A badly built bridge or a defective pair of glasses brings on immediate negative consequences, a novel doesn’t.” (Interview by A. Cattabiani, 1979)

Il sistema periodico

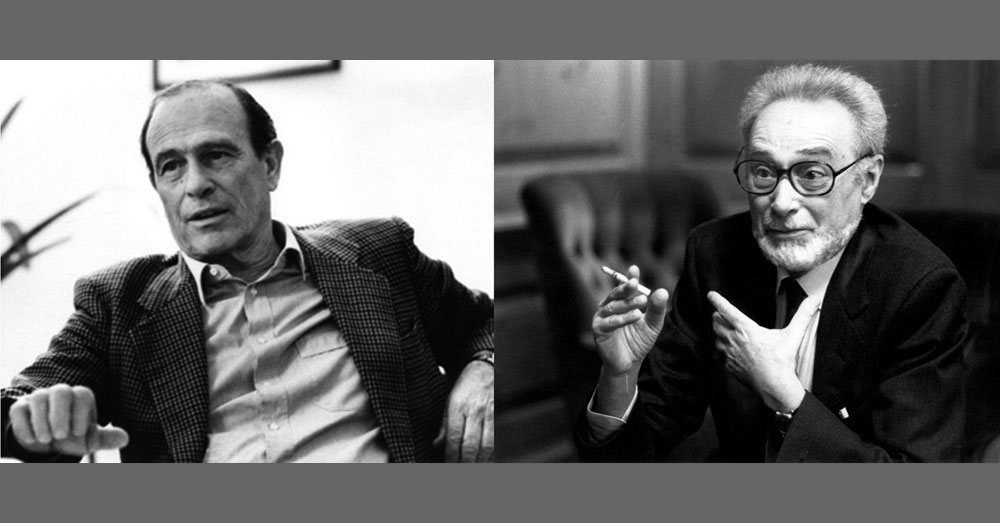

The Periodic Table was praised enthusiastically by public intellectuals including Saul Bellow, Philip Roth, Italo Calvino and Umberto Eco. It was with the English translation of this book in 1985 that Levi attained international attention.

Each chapter of the book takes the title of a chemical element combining personal recollections, philosophical considerations, metaphor and fiction.

“Perhaps as early as 1946, Primo Levi wrote a first draft of Argon, the ironic memoir of his Sephardic forebears in Piedmont that later would become the first chapter of The Periodic Table. It was the work of Levi’s imagination, not a factual account of his genealogical origins. Some of his “ancestors” were borrowed from close friends, and he made them into characters à la Calvino: non-existent knights, cloven viscounts, baron and trees. We would be wrong to read Argon literally and believe that relatives like great-grandfather Nonô Leonin and great uncle Barbaricô really did come from casale Monferrato. Levi’s page are as good a place as any to begin to learn about Casale’s tiny Jewish microcosm in the late nineteenth century and how the twentieth century destroyed it”. (Sergio Luzzatto, 2015)

The Eighties

1982

- Israeli Defense Minister Ariel Sharon allows Lebanese Christian militiamen to search the Sabra and Chatila Palestinian refugee camps in West Beirut. Between 700 and 3,500 Palestinians were massacred. Israeli forces stood by. In Israel, 400,000 marchers demand the resignation of Prime Minister Menachem Begin.

- Israeli forces invade Lebanon in what Israel called Operation Peace for Galilee.

- The Synagogue of Rome is attacked by a Palestinian terrorist unit on a Jewish holiday. Many are injured and a 2-year old boy, Stefano Gay Taché is killed.

1985 Shimon Peres orders Israeli withdrawal from Lebanon.

1985 Shimon Peres orders Israeli withdrawal from Lebanon.

- PLO member Abdul Abbas hijacks the Italian cruise ship Achille Lauro.

1986 In the Ukraine, an accident causes a reactors at the Chernobyl nuclear plant to explode resulting in thousands of victims and an ecological disaster.

The meaning of words. Interview by T. Regge, 1984

As far as my experience goes, I must say that my chemistry, which actually was a ‘low’ chemistry, almost culinary, first of all supplied me with a vast assortment of metaphors. I find myself richer than other writers because for me words like ‘bright,’ ‘dark,’ ‘heavy,’ ‘light,’ and ‘blue’ have a more extensive and more concrete gamut of meanings. For me ‘blue’ is not only the blue of the sky. I have five or six blues at my disposal… I mean to say that I have had in my hands materials that are not of current use, with properties outside the ordinary, that have served to amplify my language precisely in a technical sense. Thus I have at my disposal an inventory of raw materials, of tesserae for writing, somewhat larger than that possessed by someone who does not have a technical background. Moreover, I’ve developed the habit of writing compactly, avoiding the superfluous. Precision and concision, which, so I’m told, are my way of writing, have come to me from my trade as a chemist.”

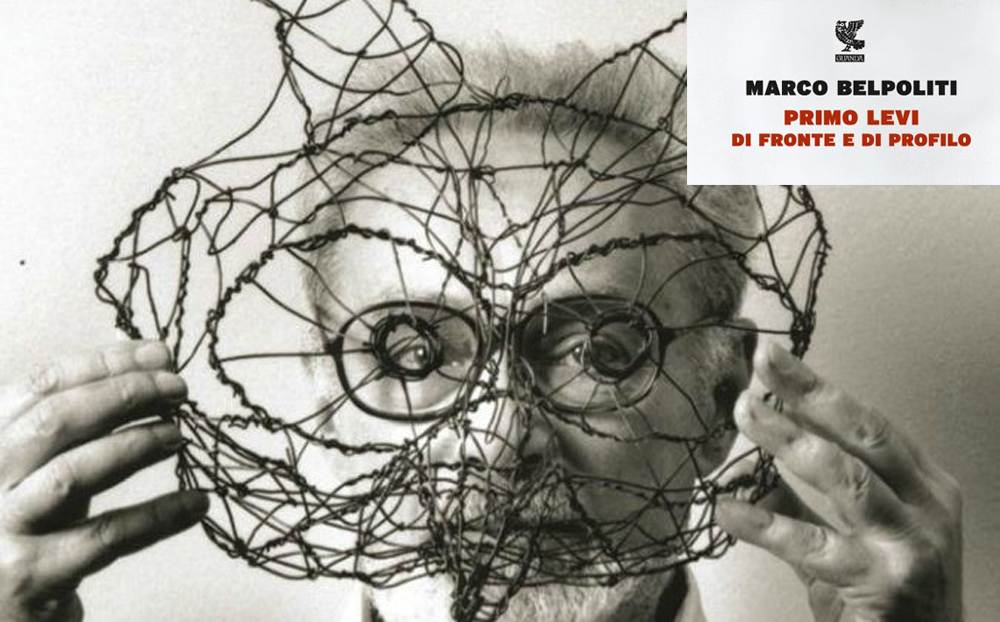

La ricerca delle radici

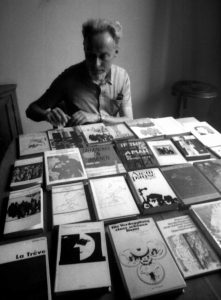

In 1981, a collection of stories dating from 1975 to 1981 was published with the title Lilìt e altri racconti. In the same year, at Giulio Bollati’s suggestion, Levi assembled a personal anthology for Einaudi. It was a selection of authors that had especially influenced his cultural education or for whom he felt affinity. The book was published as The Search for Roots and was introduced by the author’s reflection: “I accepted willingly and with curiosity the proposal to compile a “personal anthology”, not in the Borgesian sense of an auto-anthology, but in that of a harvesting, retrospectively and in good faith, which would bring to light the possible traces of what has been read on what has been written. I accepted it as a bloodless experiment, rather as one submits to a battery of tests because it is agreeable to experiment and to observe the effects. I have read a great deal because I came from a family for whom reading was an innocent and traditional vice, a gratifying habit, a mental exercise, an obligatory and compulsive way of killing time, and a sort of fairy wand bestowing wisdom.” (Primo Levi, The Search for Roots)

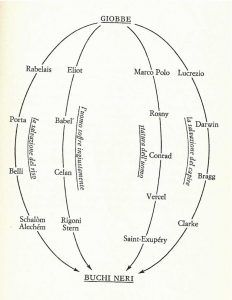

The book of Job and the Black Holes

The curious diagram that opens The Search for Roots, consists of two points linked together by four different elliptical paths. […] there are two points of departure, or destinations, which are interchangeable: Job and the Black Holes. We may ask, “Why start from Job?” Levi writes, “Because this splendid, atrocious story embodies the questions of all times, to which man has not yet found an answer, and never will, but he will seek it forever because he needs it to live, to understand himself and the world. Job is the just man oppressed by injustice”. But by what injustice is Job oppressed that he wants to understand why he suffers and contends with God from the very beginning? He knows that those who keep the commandments of the Lord will be blessed, while the guilty will receive in return sorrow upon sorrow. He knows that through suffering, God eradicates evil and guides the sinner to the path of goodness. Suffering purifies. Job knows all this and also knows that he is innocent, and he expresses it with force. What Job does not know and will never know is that he is the victim of a cruel bet between God and Satan”. (Manuela Consonni, from a lecture delivered at NYU, January 2016)

Israel

After the massacres in the Palestinian camps at Sabra and Chatila (Lebanon) together with other Italian intellectuals, Levi signed a petition, published in the newspaper La Repubblica, asking for Israel’s withdrawal from Lebanon. For this position, he was harshly criticized in the Jewish world in Italy, Israel and the US.

After the massacres in the Palestinian camps at Sabra and Chatila (Lebanon) together with other Italian intellectuals, Levi signed a petition, published in the newspaper La Repubblica, asking for Israel’s withdrawal from Lebanon. For this position, he was harshly criticized in the Jewish world in Italy, Israel and the US.

Prior to this episode, Levi had spent passionate words on Israel, expressing his admiration for the ambition and determination of those who had created the State.

“A small country born from persecution and massacres, as a shelter and a guarantee that there will never be persecutions and massacres again. A socialist country, heir of ancient and modern tradition, ins search of a difficult balance, but open to political dialogue, to all opinions, even those that we most profoundly abhor. A country created from nothing, like the earth, the earth par excellence, where one rises to build it and be built. “

“Kibbutz workers are Israel’s intellectual, technical and spiritual aristocracy. Everybody respects them and they have no enemies. The kibbutz is dominated by an atmosphere of joy and commitment. Microcosm and utopia. This utopia that is realized, has been feeding itself for decades, bore fruit and did not make victims”.

Se non ora, quando?

Going through his old papers, Levi found notes on a story that Emilio Vita Finzi had told him ten years before. In 1945, Finzi was working for a relief agency in Via Unione in Milan. A group of Russian Jews arrived. They had been partisans and had organized themselves in Russia traveling across Europe armed and ready for action. Levi decided to write a novel inspired by those men and women. He researched the story for a year before beginning writing.

Going through his old papers, Levi found notes on a story that Emilio Vita Finzi had told him ten years before. In 1945, Finzi was working for a relief agency in Via Unione in Milan. A group of Russian Jews arrived. They had been partisans and had organized themselves in Russia traveling across Europe armed and ready for action. Levi decided to write a novel inspired by those men and women. He researched the story for a year before beginning writing.

In April 1982 the book came out with the title If Not Now, When? and met with immediate success winning the the Viareggio Literary Award and the Campiello Award.

He wrote: Israel, each day less holy and more militaristic, is acquiring the behavior of other countries in the Middle East, their radicalism, their distrust in negotiations. Levi confesses his perplexity concerning the current situation: “My relationship with this country holds firm, I perceive it, in a certain sense, as my second home. I would like to be different from all other countries, but precisely because of this, I feel anguish and shame for its enterprise.

After the Sabra and Chatilla massacre

“Anyway, yes, anti-Semitism is a beast that is stirring. But this is not a reason that Diaspora Jews can put to Begin. It would not make sense to say to Begin, don’t do what you are doing because you are harming us. There are other, more important objections… There are two, one moral and the other political. The moral objection is the following: not even a war justifies the bloody arrogance shown by Begin and his men. The political objection is just as clear-cut: Israel is rapidly heading towards total isolation. It is a terrible, previously unheard-of fact […]. We must do a number of things. Realize exactly what is going on. Suppress our own impulse towards an emotional solidarity with Israel, so that we can think through coldly the errors of the present Israeli ruling class. Remove this ruling class. Help Israel rediscover its European roots, the balance of its founding fathers, Ben Gurion and Golda Meir. Not that they had spotless records, but who does?”

Kafka

In the early 1980s Levi dedicated his time to translation, a field that had always interested him.

He undertook the translation of Kafka’s The Trial for Einaudi’s new series Writers Translated by Writers.

He also translated Lévi-Strauss’ La voie des Masques [The Way of the Masks] and Le Regard éloigné [The View from Afar].

According to Genesis, the first humans had only one language: this made them so ambitious and so dexterous that they set about building a tower that reached as high as the sky. God was offended at their audacity, and he punished them in a subtle manner: not with a thunderbolt but by confounding their speech, which made it impossible for them to continue their blasphemous work. […] For many people, at a more or less conscious level, anyone who speaks another language is a foreigner by definition, an outsider, a “stranger,” and different from me; and someone different is a potential enemy or, at least, a barbarian—that is to say, etymologically speaking, a stutterer, someone who cannot speak, a quasi-non-human. […] It ought to follow that those who practice the trade of translator or interpreter should be honored, inasmuch as they strive to limit the dam- age done by the curse of Babel; (Primo Levi, On translating and being translated)

Lilit

Lilith is Levi’s third collection of short stories, divided in three sections whose titles reference the relation between tales, memory and time: Present Perfect, Future Anterior and Present Indicative. In the book, fragments from his deportation experience and his previous work, are re-organized under the symbolic aura of an ancient and counterintuitive mythological figure: Lilith. Levi learned of Lilith in Auschwitz from another inmate, Tischler, who, trying to tell Levi the story, stumbled in various, sometimes contradictory, versions. The absence of one original and indisputable version of the myth of Lilith which could be re-collected as an object of memory and mourning becomes a theme of reflection on the function and limits of memory.

Lilith is Levi’s third collection of short stories, divided in three sections whose titles reference the relation between tales, memory and time: Present Perfect, Future Anterior and Present Indicative. In the book, fragments from his deportation experience and his previous work, are re-organized under the symbolic aura of an ancient and counterintuitive mythological figure: Lilith. Levi learned of Lilith in Auschwitz from another inmate, Tischler, who, trying to tell Levi the story, stumbled in various, sometimes contradictory, versions. The absence of one original and indisputable version of the myth of Lilith which could be re-collected as an object of memory and mourning becomes a theme of reflection on the function and limits of memory.

“Lilith is a fascinating figure of the Hebrew mythology. Before that, was a Babylonian myths. She is a female devil. Many things are told about her but the most important is that she was the first woman created. She was Adam’s wife before Eve. She was not created from his rib but by splitting in two the first human being, a hermaphrodite, half man, half woman. For this reason she was equal to Adam and did not want to submit to his will. When he tried to tame her, she rebelled and became a devil. Many curious things are attributed to her, the most surprising, and, indeed sacrilegious, is that she was God’s lover.” (Primo Levi)

Primo Levi on Kafka

“This love of mine [for Kafka] is ambivalent, something close to fright and rejection. It is something like the feeling I feel for a person who is dear to me and who suffers and asks you for a kind of help that you cannot give him. I do not believe too much in the laughter than Brod talks about. Maybe Kafka laughed when he was telling stories to his friends, […] You feel like one of his characters, sentenced by a vilifying and inscrutable court, a tentacle-court that invades the city and the world, nesting in slimy attics as well as in the dark solemnity of the cathedral. Or, [you feel like a character] transformed into an insect that is awkward and burdening, unseen by all, desperately alone, obtuse, unable to communicate and to think, by then able only to suffer. We can feel attracted even by somebody who is very different from us exactly because he is different. If it were not like this, writers, readers, and translators would be stratified into rigid castes, like the Indian castes. There would be no connections across fields nor crossover fecundations. Everybody would read only the writers who are their blood relatives. The world would be (or would appear) less varied and new ideas would no longer be born. Now, I love and admire Kafka because he writes in a way that is totally closed off from me. In my writing, in good or in bad, knowingly or not, I have always tended to pass over from the dark to the light. (It seems to me that [author Luigi] Pirandello said this. I don’t know where.) This is like a filter-pump, which sucks in dirty water and expels decanted water, maybe even sterile water. Kafka treads down the path the opposite way. He endlessly unravels the hallucinations that come out of incredibly deep faults in the earth and never filters them. The reader feels them gurgle with germs and spores. They are pregnant with meanings that scald. But we are never helped in tearing the veil or in going behind it to see what it is hiding. Kafka never touches the earth. He never condescends to give us end of Ariadne’s thread.”

Poetry: Ad ora incerta

In October 1984 Garzanti published a collection of Levi’s poems entitled At an Uncertain Hour, a title taken from Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner. The Italian collection contained the twenty-seven poems previously published by Scheiwiller in 1975, thirty-four that were published in the newspaper La Stampa and various translations (from an anonymous Scottish poet, Heine, and Kipling).

“In all civilizations, even in those without writing, many people – illustrious or obscure – feel the need to express themselves in verse and they subject themselves to it. Hence they secrete poetic material, addressed to themselves, to their neighbors, or to the universe, material that can be full-bodied or bloodless, eternal or ephemeral. Poetry was certainly born before prose. Who has never written verses? I am a man. I too – at irregular hours, ‘at uncertain hours,’ gave in to this shove. As far as I understand, it is inscribed into our genetic heritage. At certain times, poetry seemed to be more ideal than prose for communicating an idea or image. Primo Levi”.

Conversations with Tullio Regge

Levi and Regge met in June 1984 and this spontaneous, free-flowing conversation was recorded. It touches upon a varied range of arguments with great freedom – the years of their early education and relationship with school, what they read, their professional experiences, the responsibilities of the sciences, the future of mankind, the birth of the universe, the most recent hypotheses of contemporary physics (from elementary particles to cosmology) as well as the various stages of the scientific ‘romance’ that consisted in the articulation of the theory of relativity and the debate that it provoked. Levi talks about how science affected his activity as a writer. Meanwhile, Regge re-evokes the great characters that he met during his long stay at Princeton, such as Gödel, Heisenberg, Oppenheimer, and Dyson, with Einstein was always looming in the background. When the book came out, Massimo Piattelli wrote: ‘This little book took a couple of hours to read, but these were hours that came from heaven. This is one of those reads that reconcile us with existence and, for an instant, make sense of it’.” [Einaudi, 1994]

Poetry, interview by G. Nascimbeni, 1984

“I am a man who believes very little in poetry and yet I practice it. There is some reason for this. For example, when my verses are published on the third page of La Stampa, I get letters and phone calls from readers who show me their agreement or disagreement. If one of my stories is published, the response is not as lively. I have the impression that poetry in general is becoming a portentous instrument of human contact. Adorno has written that poetry could not be written after Auschwitz, but my experience was the opposite. Back then (1946-47) it seemed to me that poetry was more appropriate than prose for expressing what was weighing me down. Saying poetry, I am not thinking of anything lyrical. In those years, at most I would have reformulated the words of Adorno: after Auschwitz, poetry cannot be written except about Auschwitz.”

The Periodic Table: An American success

In November the American edition of The Periodic Table was published to extremely favorable reviews. Saul Bellow’s endorsement appeared in the back cover: “The book it is necessary to read next. After a few pages I immersed myself in The Periodic Table gladly and gratefully. There is nothing superfluous here, everything this book contains is essential. It is wonderfully pure and beautifully translated.”

Bellow’s endorsement sparked a series of translations of Levi’s books in several countries. His work was also reviewed favorably in the New York Times in separate articles by Neal Ascherson, Alvin H. Rosenfeld, and John Gross.

He wrote an introduction to the new paperback edition of Commandant of Auschwitz. A Memoir by Rudolf Höss.

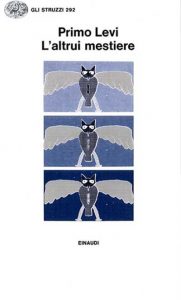

L'altrui mestiere

In January 1985 Levi gathered about 50 articles that had been published mainly in the newspaper La Stampa and collected them under the title Other People’s Trades. Italo Calvino commented as follows: These pieces “respond to his vein as encyclopedist of agile and meticulous curiosities and as moralist of a moral that always starts out from observation […]. The most representative from among the objects of Levi’s encyclopedic attention are words and animals. (Sometimes one could say that he tends to fuse his two passions into a zoological glottology or into an ethology of language.) In his linguistic wanderings what dominate are his pleasant reconstructions of how words deform with use, in the attrition created between dubious etymological rationality and the dismissive rationality of speakers.” (Calvino, 1985)

Travel to America

In April 1985, Levi traveled to the United States for a series of public engagements. He talked at various universities on the occasion of the translation of If Not Now, When? The English translation of his novel included an introduction by Irving Howe. He visited Claremont College near Los Angeles, Bloomington (Indiana), Boston and New York. He described his impressions of his trip in “Among the Peaks of Manhattan,” which appeared in La Stampa on June 23, 1985 [later anthologized in The Mirror Maker].

During his visit to the United States, Levi was presented mostly to Jewish audiences, whose focus on his degree of Jewishness impressed him as awkward. He conceded that the argument for European Jews to settle in Israel and “rebuild” themselves was a powerful one. However, he expressed his reservations.

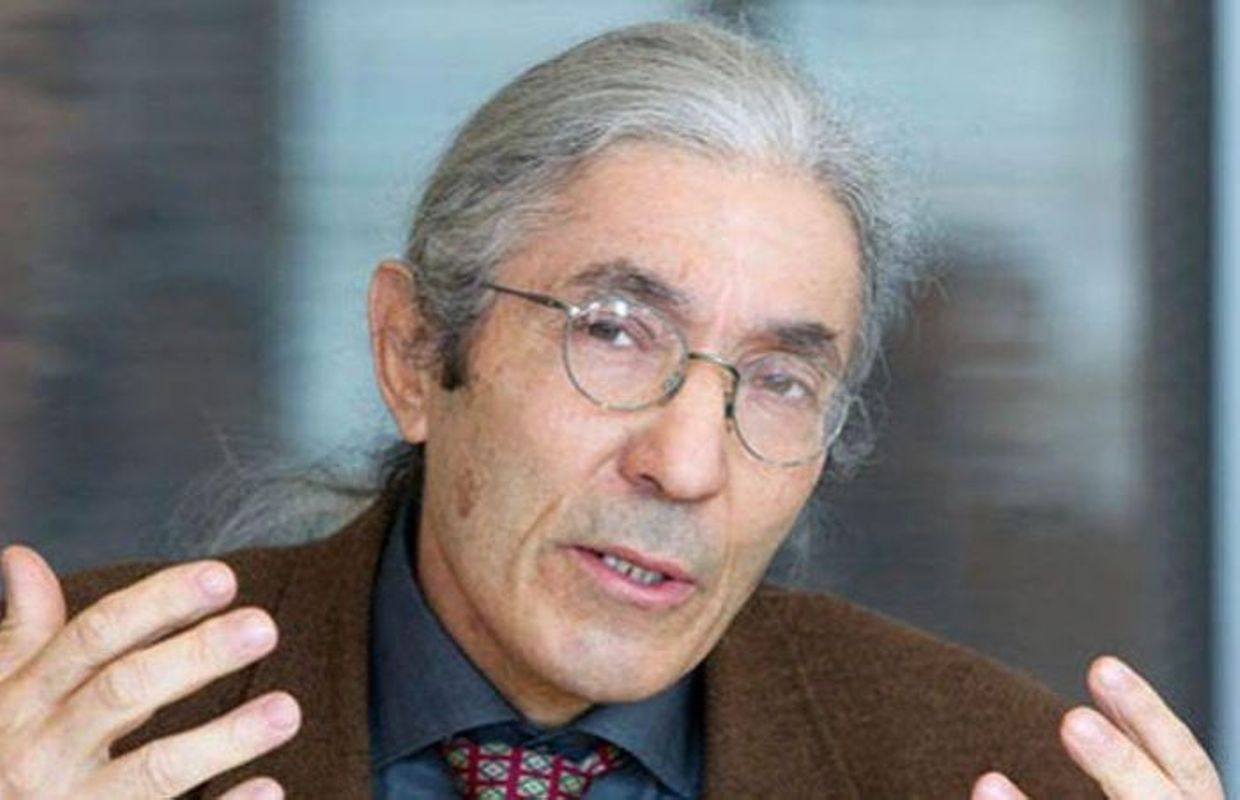

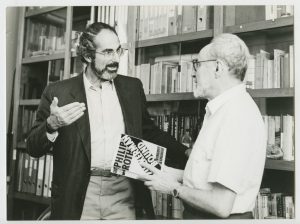

Philip Roth, I sommersi e i salvati

In April 1986 he published The Drowned and the Saved, a summation of his reflections on the concentration camp experience, and his intellectual and ethical testament. The Wrench and Moments of Reprieve (a selection from the stories in Lilìt) were published in the United States and If Not Now, When? in Germany. Levi traveled to London, where he met Philip Roth, and then on to Stockholm.

In September Levi was visited by Philip Roth in Turin for an interview to be published in the New York Times Review of Books. The interview was published on October 12 and then translated and published in La Stampa on November 26-27. Roth’s interview brought Levi’s work to a large readership and prompted a new level of appreciation of his work in the U.S.

America

“But it was a simplification. If you thought about the actual situation, the objective conditions … the country wasn’t empty for one thing. I had trouble with this in America. I had to give a talk to a group in Brooklyn and for the first time in my life I found myself in front of a totally Jewish audience. All old and all Jewish. I gave my talk, which I’d written in England. I’m not sure how much they grasped, given my terrible accent. As soon as I finished, they started asking questions about Israel and where I stood on the Arab-Israeli conflict. When I started to explain that I thought Israel was a mistake in historical terms, there was uproar and the moderator had to call the meeting to a halt.” (Interviewed by Greer in Belpoliti & Gordon, 2001)

Chernobyl

1986 A catastrophic nuclear accident occurred on 26 April Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

On September 21 Levi wrote an article on the issue of the responsibility of scientists in La Stampa: “Whether you are a believer or not, whether you are a ‘patriot’ or not, if you are given a choice, do not let yourself be seduced by material or intellectual interests, but choose from the field which may render less painful and less dangerous the journey of your contemporaries, and of those who come after you. Don’t hide behind the hypocrisy of neutral science: you are educated enough to be able to evaluate whether from the egg you are hatching will issue a dove or a cobra or a chimera or perhaps nothing at all.” (“Hatching the Cobra,” The Mirror Maker, 2002)

Revisionism

1987 A controversy over political revisionism broke out in Germany. Levi commented on this in La Stampa in a piece entitled “The Black Hole of Auschwitz”.

In the essay to which Levi refers, Ernst Nolte argued that the Holocaust was not unique and therefore the Germans should not bear any special burden of guilt for the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question”. He stated that the Germans needed to have a positive sense of national identity to make the “past that will not go away” finally “go away”. In his view, there is no moral difference between the crimes of the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, and even, more controversially, the Holocaust was something that the Germans were allegedly forced to conceive out of a fear of what the Soviet Union might to them as well as because of the actual threat Jews posed to Germany.

The Black Hole of Auschwitz

“The current polemic in Germany between those who are inclined to banalize the Nazi massacres (Nolte, Hillgruber) and those who would claim its uniqueness (Habermas and many others) cannot be a matter of indifference to us. The thesis of the former is scarcely new: there have been massacres down the centuries, above all at the beginning of our own century against the ‘class enemy’ in the Soviet Union, and thus near the German borders. Over the course of the Second World War we Germans did no more than adopt a practice that was dreadful, but now well-established: an ‘Asiatic’ practice of massacre, mass deportation, merciless exile to hostile (inhospitable) regions, torture and the splitting up of families. Our only innovation was a technological one: we invented the gas chambers… Now, the Soviets cannot be absolved…. The new German revisionists, then, tend to present Hitler’s massacres as a preventive defense against an ‘Asiatic’ invasion. This seems to me as an extremely fragile thesis… It is true that ‘the Gulag came before Auschwitz’ but we should not forget that the aims of these two infernos were not the same. The first was a massacre between equals; it was not based on racial supremacy, nor did it divide men into the superman and the subhuman; the second was based on an ideology imbued with racism…. Not even the pages of Solzhenitsyn, which quiver with well-justified furor, suggest anything similar to Treblinka or Chelmno, which did not produce work, were not concentration camps, but ‘black holes’ destined for men, women and children guilty of only being Jews…. And I do not see how this ‘innovation’ [gas chambers] could be considered marginal, or be attenuated with an ‘only.’ These were not imitations of ‘Asiatic’ methods, they were decidedly European; the gas was produced by reputable German chemical factories, and it was to German factories that the hair of massacred women was sent, while the gold extracted from the teeth of the dead bodies was destined for German banks. All of this is specifically German, and no German should ever forget it; nor should he forget that in Nazi Germany, and only in Nazi Germany, children and the sick were also sent to an atrocious death in the name of an abstract and ferocious radicalism which has no equivalent in modern times…. If Germany today desires the position which is rightfully hers amongst European nations, she cannot, and must not, whitewash her own past.” (Levi, 1987)

I sommersi e i salvati

“I must repeat: we, the survivors, are not the true witnesses. This is an uncomfortable notion of which I have become conscious little by little, reading the memoirs of others and reading mine at a distance of years. We survivors are not only an exiguous but also an anomalous minority: we are those who by their prevarication or abilities or good luck did not touch bottom. Those who did so, those who saw the Gorgon, have not returned to tell about it or have returned mute, but they are the “Musulmann,” the submerged, the complete witnesses, the ones whose deposition would have a general significance.” (The Drowned and the Saved)

1919-1987

In March The Periodic Table is published in French and German translations. Levi underwent surgery. On April 11, 1987 he fell to his death from the stairwell of his home in Turin. Some believe he committed suicide.

A man of the twentieth century, Levi will continue to be a towering moral guide, with a broad universal humanist appeal well into the future, while remaining tied to the personal, historical and cultural events that shaped his life.

Credits

The above is an abridged version of a Primo Levi chronology edited by Ernesto Ferrero. Centro Internazionale di Studi Primo Levi – All rights reserved. Editing by Alessandro Cassin and Natalia Indrimi