In a Complex New Book, Algerian Novelist Boualem Sansal Pays Tribute to Primo Levi.

Alessandro Cassin

The German Mujahid, Europa Editions, 2009, by the Algerian writer Boualem Sansal is being marketed as the first Arab novel to confront the Holocaust. What it is above all, is a powerful literary inquiry into the hopelessness of a generation caught between civil war (Algeria in the 1990’s) and the radicalization of Islamic militants in the bleakness of French banlieues. Against this backdrop, Sansal masterfully devises a novel which expands to confront universal themes such as the weight of history, the relation between personal and collective guilt and the different forms of man made horror.

The opening is a shocker: Malrich (a contraction of the names Malek and Ulrich) an Algerian youth living aimlessly in a grim Parisian housing project, is given by the police the diary of his successful brother. His brother Rachel (Rachid Helmut) had committed suicide at age 33. He chose to die by carbon monoxide gas from the exhaust of his car in the garage of his plush house. After shaving his head and wearing striped pajamas, surrounded by piles of books about the Holocaust. Based on a true story, the novel is a drama of three men: an absent father (a former Nazi officer) and his two Algerian born sons who reveal themselves through their respective diaries. Rachel, the elder, had been sent to study in France where he became an engineer. He attended the university, married well and landed a dream job with a multinational company. One day in April 1994 he learns from a news report that his German father and Algerian mother, along with the majority of the population of the remote Algerian village of Ain Deb were brutally murdered by Islamic fundamentalists. As he returns to the village to pay homage to his parents, he discovers the real identity of his father: that of a Waffenn SS officer active in death camps. He had eluded justice after the war and managed to hide in Algeria assuming a new identity. In the two intense years chronicled in his diary, Rachel reads everything he can find about the Holocaust, travels to all the places where his father had been stationed, all in a desperate attempt to make sense of what made him willingly take part in the extermination of Jews. When he discovers Primo Levi’s If This Is A Man, Rachel adds to the opening poem his own verses:

“Your offspring do not know;

They live, they play, they love.

And when what was appears to them;

The tragedies bequeathed by their parents;

They are faced with strange questions,

Glacial silences,

Nameless shadows.

My house has crumbled, grief has made me powerless,

And I do not know why.

My father never told me.”

Progressively the horror and guilt paralyze Rachel, he becomes obsessed by his research, unable to work, alienated from his wife. He sees no way out but to expiate his father’s sins by his own suicide.

If we take out the Algerian childhood in Rachel’s story, we are left with a fictional account that closely matches the studies by Austrian journalist Peter Sichrovsky. in Born Guilty: Children of Nazi Families, Basic Books, 1989. Sichrovsky put together a collection of interviews with Austrians and Germans whose fathers were accused of Nazi war crimes. The conclusions were that almost every one of them believed the same horrific events could happen again…

In stark contrast, Malrich’s own diary is one of a hoodlum, whose language is that of the street and whose adolescence is brutally interrupted by his brother’s suicide and the revelations of his diary. After reading his older brother’s detailed account of the Nazi “final solution”, Malrich – who had known nothing about Nazism and totalitarianism – begins to see the behavior of the local Imam and extremist Islamic militants, as “Nazi like behavior”. Sansal does not mean to literally equate the situation in Paris’ banlieues to that of concentration camps (the analogy is made relentlessly by the disgruntled teenager narrator).

By alternating chapters from the two diaries, the author creates the pacing and rhythm of the narrative, shedding light into the lives, language and mental process of these two contrasting and persuasive characters.

An Arab novelist that compares the consequences of violent radical Islam to those of the extermination of the Jews by the Nazis is in itself explosive. Sansal manages to bring his two protagonists to this shocking conclusion through a series of literary devices rather than a political agenda.

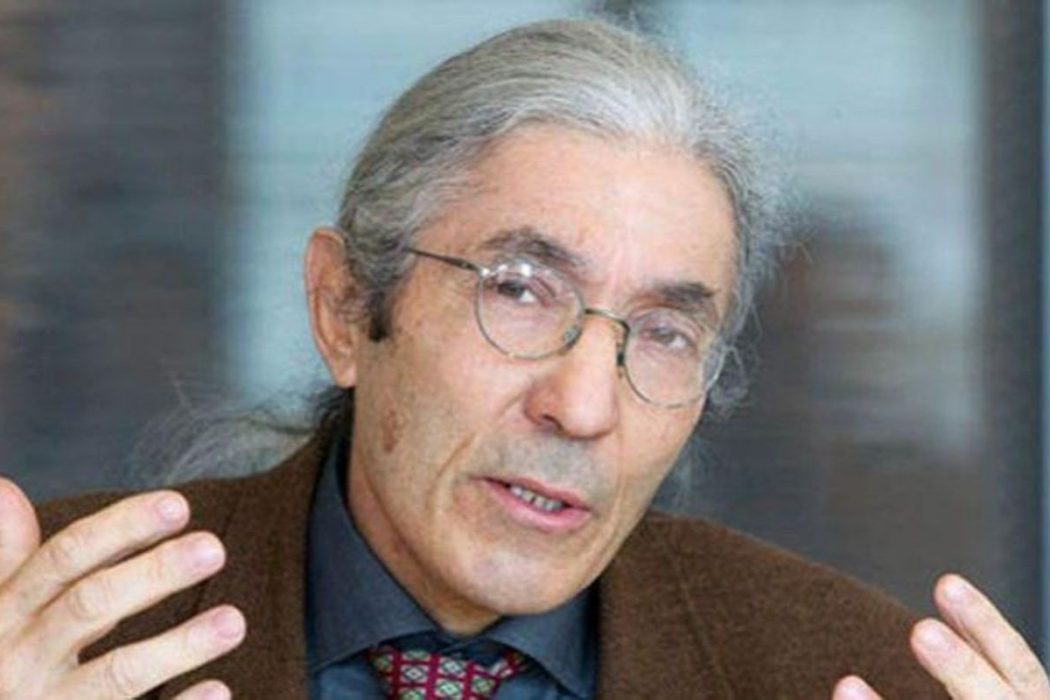

Passionate, courageous and relevant, this novel takes a strong stance against oblivion, historical manipulation and revisionism. The German Mujahid stresses the decisive role of individual and collective memory in shaping identity, touching upon the delicate question of what it means to grow up half Algerian in Europe. For the protagonists, confronting and understanding the past becomes a matter of both psychological and physical survival. It is also the first novel in the Arab world to address the Holocaust, an event not taught in schools, or mentioned in the media in the Arab world. Clearly informed by current events, this novel employs both the specifics of north African post colonial strife and the human tragedies of the protagonists to address larger universal themes regarding the human condition. A late bloomer, Mr. Sansal, born in 1949, began his career as a novelist at age 50. Until then he was a successful economist, engineer and a high ranking official within Algeria’s Ministry of Industry. After the assassination of President Boudiaf in1992, whom the author considered a friend, Sansal began writing about his country and eventually had his fiction works published in France by Gallimard. No surprise that The German Mujahid was banned in Algeria. The more one reads, the more one fears for the author’s life, who continues to live there with his wife and two daughters…