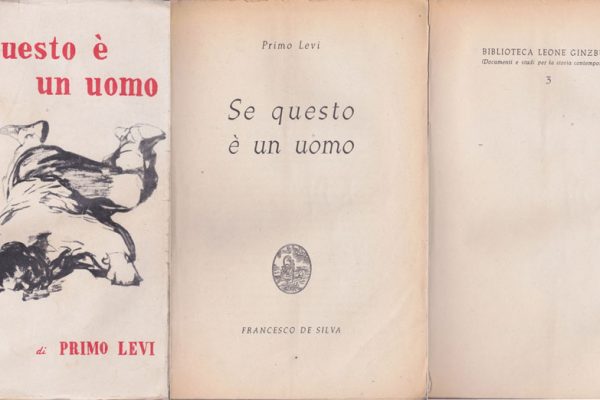

Don Harrán, Sarra Copia Sullam: Jewish Poet and Intellectual in Seventeenth Century Venice, University of Chicago Press, 2009

The first Jewish woman to leave her mark as a writer and intellectual, Sarra Copia Sulam (1600?–41) was doubly tainted in the eyes of early modern society by her religion and her gender. This remarkable woman, who until now has been relatively neglected by modern scholarship, was a unique figure in Italian cultural life, opening her home, in the Venetian ghetto, to Jews and Christians alike as a literary salon.

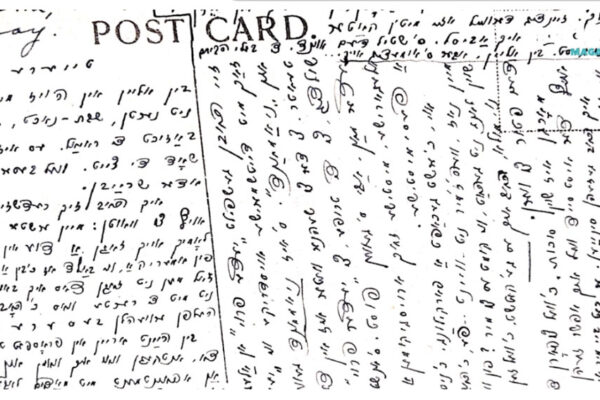

For this bilingual edition, Don Harrán has collected all of Sulam’s previously scattered writings—letters, sonnets, a Manifesto—into a single volume. Harrán has also assembled all extant correspondence and poetry that was addressed to Sulam, as well as all known contemporary references to her, making them available to Anglophone readers for the first time. Featuring rich biographical and historical notes that place Sulam in her cultural context, this volume will provide readers with insight into the thought and creativity of a woman who dared to express herself in the male-dominated, overwhelmingly Catholic Venice of her time.

Benjamin Ivry, The Forward

According to Don Harrán, Sarra Copia Sulam was the first Italian Jewish woman to “excel” as a public literary figure, writing in various forms and leaving a “personal imprint on them.” She was a kind of Susan Sontag of the Venetian Ghetto. Sulam was also prominent because of her beauty and wealth (her husband was a banker/moneylender whose brother, also a banker, was likely a patron of Salamone Rossi).

Harrán, Professor Emeritus of Musicology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, has published a series of landmark studies, including “Salamone Rossi: Jewish Musician in Late Renaissance Mantua” (Oxford University Press, 2003), about the Italian Jewish composers of the late Renaissance and early Baroque. Harrán’s latest publication, from the University of Chicago Press, “Sarra Copia Sulam: Jewish Poet and Intellectual in Seventeenth-Century Venice” is equally rewarding and enlightening.

Sulam’s public literary career lasted only from 1618 to 1624, after which she focused on charitable works. Her writings include lyrical effusions like “Sonnet to the Human Soul”:

O di vita mortal forma divina

E dell’opre di Dio meta sublime

In cui sé stesso e ‘l suo potere esprime…O divine form of mortal life

And sublime end of God’s works,

In which He expresses Himself and His power….

There is also a lengthy correspondence with the Catholic author Ansaldo Ceba, who ardently tries to get her to convert, which Sulam refuses to do, essentially telling Ceba to go get circumcised (!)

Sulam also tempts Ceba with the joys of Jewish cooking by sending him bottarga, a delectable pressed caviar described succinctly and succulently in Jayne Cohen’s “Jewish Holiday Cooking: A Food Lover’s Treasury of Classics and Improvisations” (Wiley, 2008).

Also a gifted musician at a time and place where a few Jewish women excelled in this domain, Sulam spoke out at a time when women were often seen as possessions or prisoners of their spouses (Horrifically, Sulam’s own sister Diana was blinded by her husband because he suspected her eyes of straying towards other potential lovers). Sarra Copia Sulam is a voice to be remembered.