Italian Jewry in the Early Modern Era: Essays in Intellectual History

.

Research does not always proceed according to a predetermined plan.

In some cases, the opposite is true: only when a work is completed can we observe its fundamental inspiration, which was implicit from the start. The essays presented in this book demonstrate the latter: the coherence of the collected pieces—the common elements that connect them—was visible only post factum. Only in collecting some of the articles I wrote between 1998 and 2012 was I able to see clearly the common elements in theoretical approach and conclusions which, when viewed as a whole, reveal a rather uniform result.

The motivations that drive the scholar to choose a certain field of research, a specific subject within that field, and the way that subject will be approached are difficult to pin down, perhaps even mysterious. But within that choice itself lies a large measure of the results: in the sciences, or at least in the human sciences, the answers one finds are guided largely by the questions one asks.

My field of research is the intellectual history of Italian Judaism. Though this choice obviously stems from my own experiences and cultural training, my choice of eras is the result of an attraction that is difficult to explain, whose motivations are probably found in that murky area between emotion and intellect, or in the inputs from emotion to the intellect, guiding its choices.

The period covered in this book is called “Modern” in the French and Italian historiographical traditions and “Early Modern” in Anglophone countries.

It ranges from the Renaissance at its height in the first decades of the sixteenth century to the first half of the eighteenth century, on the threshold of the Enlightenment. According to the classical scansion of Jewish history,this period is called the “Age of the Ghetto”—long considered by historians,from the nineteenth century until the revision of a few decades ago, as an era when the repressive policies of the Catholic Church caused Italian Jewish communities to fold in on themselves, an era of intellectual obscurantism and demographic decline.

However, scholars like Baruch Sermoneta and Robert Bonfil (and many others in their wake) have shown that exchange with non-Jewish society became more intense in the Age of the Ghetto, and that some of the intellectual forms that developed in the Jewish world were completely analogous to those in the Christian world.

The era of emancipation, situated in the second half of the eighteenth century, was actually preceded by a series of apparently contradictory processes. Though, on the one hand, philosophical and scientific rationalism spread among Catholic and Jewish intellectuals, this period also saw the diffusion of an opposite attitude: a religious devotion that in the Catholic world inspired the values of the Counter-Reformation and that in the Jewish world took the form of Kabbalah.

The history of these two hundred years is, at its base, the history of tension and dialectic between these two positions. It was an age marked by contrasts, paradoxes, and extremely significant personal crises. Authors who denounced the inadequacy of medieval science, which was founded on fossilized and superseded knowledge, became devoted penitents and adherents to religious tradition; the most intransigent kabbalists recognized the obscurity of their doctrine in the form in which it had been handed down, and tried to adapt it to the rationalism of contemporary science. Hebrew prose and poetry were transformed, while at the same time literary translations into Italian multiplied, and the use of Italian (the “national” and “modern” language) became increasingly frequent under the pen of many Jewish authors.

In sum, it was a time when many of the elements of the era of emancipation were being prepared, yet the richness of Jewish culture, its intellectual forms and its linguistic expression, was maintained; in other words, a time before the rapid abandonment of culture that resulted from the integration of a small minority into a much more populous society, leading to so-called “assimilation.”

However, the common traits of this period became clear to me only in collecting and combining these essays—and perhaps even in the drafting of these present lines, which must serve as a general and unifying introduction.

A similar observation can be made regarding the topics and authors that I chose to study. It is not always easy for researchers to remember their first encounters with an author or a work, and the considerations (in that early stage, we usually rely on simple intuition) that led to the dedication of months or years of study.

Post factum, I can say that all of the authors discussed in this book simultaneously demonstrate a strong anchoring in traditional Jewish culture (biblical-rabbinic) and a clear tendency toward engagement with non-Jewish culture, whether philosophical, scientific, literary (Italian and, less commonly,Latin), or theological (Christian). The first three areas have, a priori, aneutral valence insofar as they do not touch on the foundations of the Jewish religion and can represent a zone of exchange and encounter with non-Jews:

Italian rabbi-philosophers cited Muslim authors like Averroes and Christian authors like Thomas Aquinas, doctors corresponded with their Catholic colleagues, and poets were explicitly inspired by prestigious Italian authors, above all Dante. For a large portion of the era we are studying here, during which fundamentalism prevailed, these “neutral” areas were considered “impure” and extraneous with respect to the “authentic” tradition handed down to the Jews (and only to the Jews). But connections with “the other” never stopped: they simply took other forms.

Some of these authors tried to establish contact with Christians on the (obviously very sensitive) level of theology. There were those who tried to show the common threads of Judaism and Christianity and those who, through polemicizing on some essential points of Christian belief, showed respect and openness to a religion that represented otherness par excellence.

The figures reviewed in this book do not necessarily seek harmony between Jewish and non-Jewish elements: in some cases, each of these sets of elements belonged to separate and seemingly mutually exclusive phases in their biographies; in other cases, the non-Jewish elements are implicit, buried beneath a thick layer of apparently self-sufficient Jewish elements, leaving it to the researcher to find and feature them—a good example of the answers being guided by the questions.

One of the recurring terms in this book is modernity. The concept is suggested by the anti-traditionalist positions of some authors (like Avraham Portaleone in his younger period) and explicitly used by another fundamental figure of this period, Leone Modena. Indeed, this term appears in the original titles of some of my articles, as well as in publications or research seminars I have coordinated over the last several years.

There are no doubt some good reasons to attribute a kind of “primogeniture” in terms of modernity to Italian Jewish society and the culture it expressed.

If no one doubts the Ashkenazi (German and Eastern European) origins of many fundamental realities of contemporary Judaism (Zionism, Jewish Socialism, Hasidism, the rebirth of the Hebrew language, and the scientific study of traditional heritage), if we can, with extremely good reason, see the Jews of seventeenth-century Amsterdam as the “prototype” for modern Jews who incline toward secularization (of whom Baruch Spinoza is only the most visible representative),2 it is equally true that, as far as the size and duration of the phenomenon is concerned, the Italian community is most anciently and most broadly “modern.”

But what do we mean by “modern”?

Is modernism identified with secularization? Does it suggest an anti-traditionalist, progressive, and optimistic ideology? Or does it simply designate a chronological period between the Medieval, perhaps Renaissance era and the contemporary age, which is defined by many as “post-modern”?

Although founded on solid grounds, the term “modernity” presents (along with a certain dose of the arbitrariness inherent in all denominations of temporal scansion) the inconvenience of finality. When we talk about modernity, there is the implication that the preceding age was the preparation and the modern age was the fulfillment. Despite the fact that nineteenth-century historical philosophies, with their visions of the present as the completed and somehow final result of a long process, seem to have been eclipsed, the idea of the present as the perfection of the past dies hard.

Of course, there is no reason to consider the contemporary Jewish condition any more perfected than that of, say, the 1600s. This is why one should be careful when using a debatable term like modernity, and instead emphasize the constant dialectic, among Italian Jews in those years, between the tendency to exploit traditional Jewish cultural heritage and the explicit, unconfessed, or unconscious appeal to different forms of Italian culture.

At base, theirs was, as Moritz Steinschneider defined it (referring to linguistic levels), an “amphibious” life, in which Jewish and Italian elements combined with considerable ductility.

I would like to express an intellectual debt to Robert Bonfil. In addition to the general formulation of the book, which was certainly influenced by his approach, some of the essays contained here were developments of theGreek-Italian-Israeli scholar’s concisely expressed intuitions.

My hope is that these elaborations and other original contributions will help others to see things a little differently, showing them new aspects of the fascinating Jewish-Italian intellectual history of the period.

[From the Introduction to Alessandro Guetta’s Italian Jewry in the Early Modern Era: Essays in Intellectual History, Academic Studies Press, 2014]

About the book

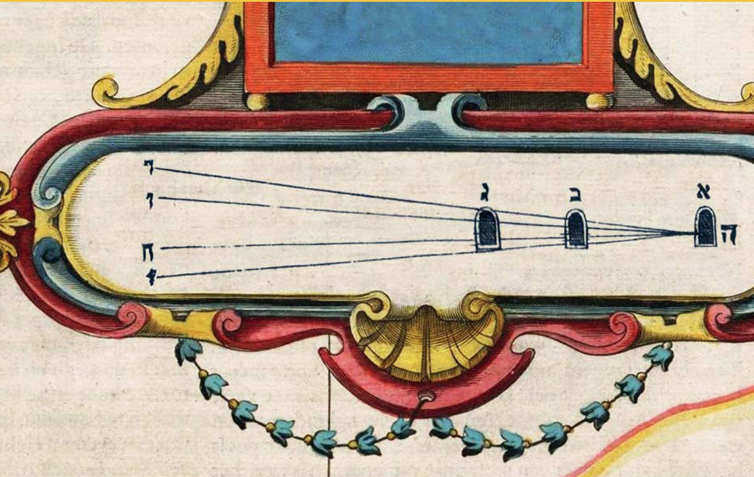

Between the years 1550 and 1650, Italy’s Jewish intellectuals created a unique and enduring synthesis of the great literary and philosophical heritage of the Andalusian Jews and the Renaissance`s renewal of perspective. While remaining faithful to the beliefs, behaviors, and language of their tradition, Italian Jews proved themselves open to a rapidly evolving world of great richness. The crisis of Aristotelianism (which progressively touched upon all fields of knowledge), religious fractures and unrest, the scientific revolution, and the new perception of reality expressed through a transformation of the visual arts: these are some of the changes experienced by Italian Jews which they were affected by in their own particular way. This book explores the complex relations between Jews and the world that surrounded them during a critical period of European civilization. The relations were rich, problematic, and in some cases strained, alternating between opposition and dialogue, osmosis and distinction.

“Nine momentous essays in intellectual history of Italian Jewry in the Early Modern Period, by one of the most skilled specialists of the field. Topics deal with a wide range of issues, such as philosophy, Kabbalah, humanism, politics, allegorical representations of space, and others. Although deeply scholarly, the well-designed approach of the author will undoubtedly fascinate many broadminded ordinary readers.” — Robert Bonfil, Emeritus Professor of Jewish History, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

“Alessandro Guetta is one of the leading scholars of the cultural history of Italian Jewry in early modern times today. Italian Jewry in the Early Modern Era brings together a fine collection of papers published over the last ten years, some of which were originally published in Italian and French, and now reproduced in an English translation. These nine studies, covering the period from the late fifteenth century to the early nineteenth century, focus on the diverse aspects of the process of modernization of Italian Jewish culture from the Renaissance until the Jewish Enlightenment.” — Abraham Melamed, Professor of Jewish History and Thought, University of Haifa