It is a rare pleasure to turn the last page of a book, and remain in a state of bewilderment with the feeling of having traveled a road previously unknown. Such were my feelings upon finishing Nuto Revelli’s Il disperso di Marburg, a curious and unclassifiable book, regrettably available only in an Italian edition published by Einaudi in 1994, in the Coralli fiction series. One would hesitate to define it a work of fiction, a diary, a historical account or a form of historical inquiry, yet perhaps it is all these things together, and more. The back flap accurately defines it as “a remarkable, fascinating story linked to the great events of the Second World War and the drama of the German occupation in Italy, which at the same time, offers us a narrative of inner political struggle. A book of memory, testimony, and ethical reflection. Above all an example of intellectual courage”.

Michel Foucault once suggested the need “to write the history of the present,” which, in a sense, is precisely what this book achieves, and what compels me to attempt an introduction to a book and an author largely unknown to the English-speaking reader.

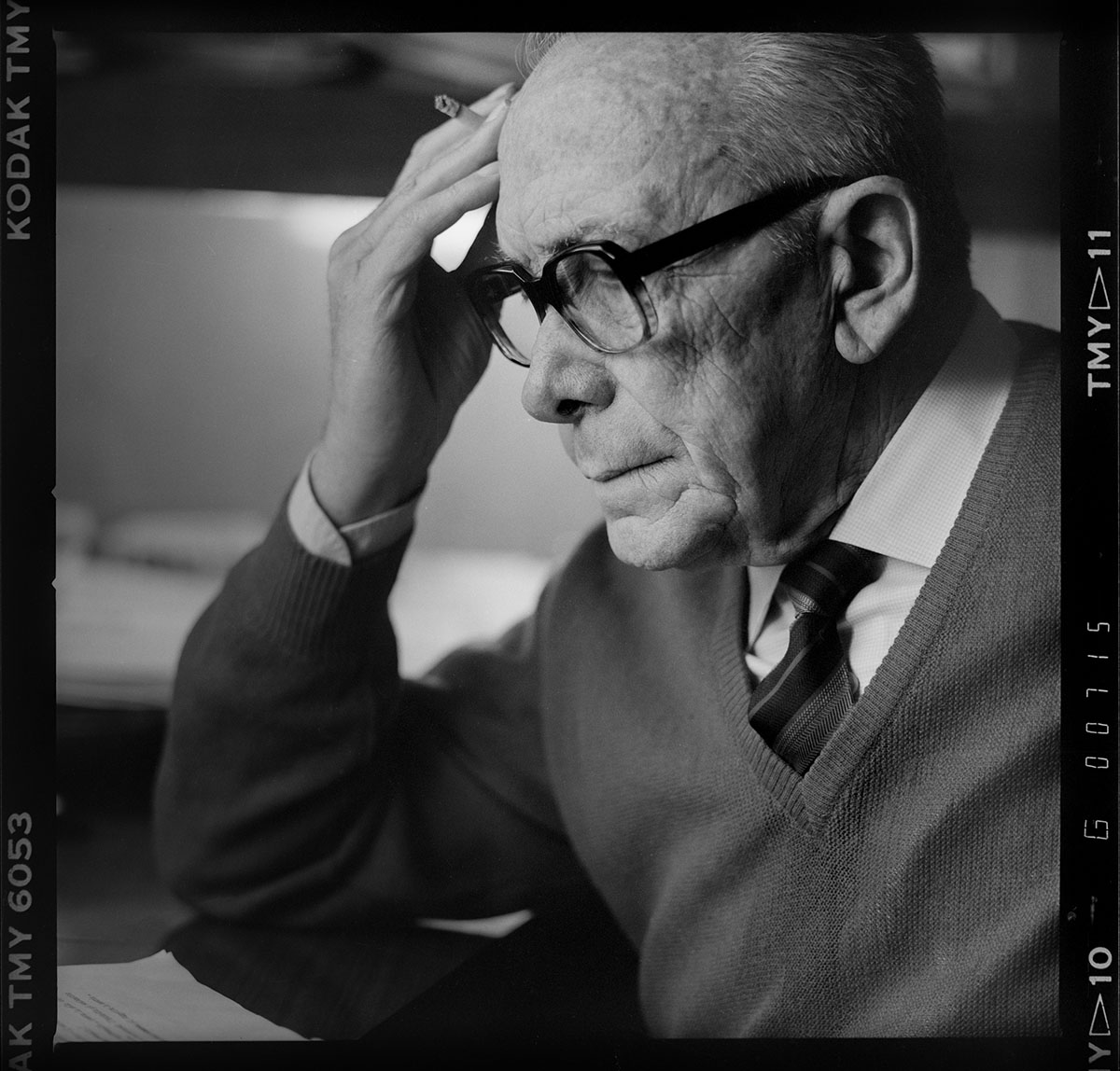

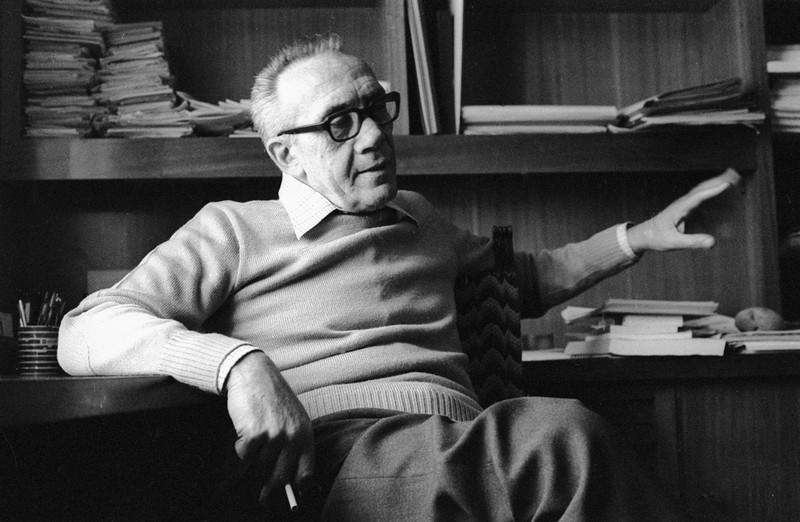

Benvenuto “Nuto” Revelli, was born in Cuneo, in 1919 and died in the same city, in 2004. His life was marked by war, first by participating in it, and later writing about it with unsurpassed honesty and directness. After going through Fascist Italy’s educational system, Revelli became an officer in the Italian army’s elite “Cunense” mountain division and was sent to the Eastern front to fight the Russians in July 1942. That winter, the Soviets encircled the entire Italian Army on the Don. Thousands of men fell in combat, thousands more were taken prisoners and a great many more succumbed to the cold, hunger and exhaustion.

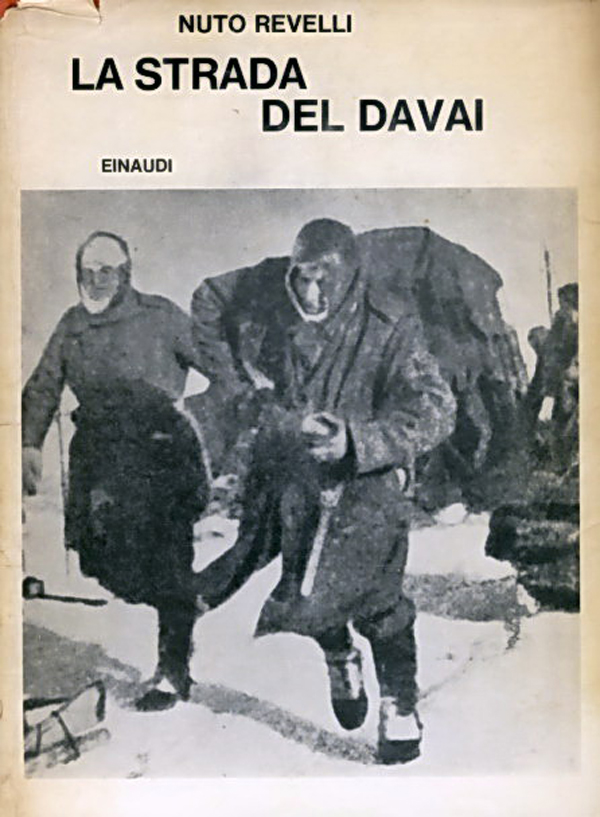

Revelli’s division was hit particularly hard, with only a small percentage of its troops struggling back to Italy. That winter in Russia, the Italians suffered roughly 75,000 dead, more than in their six-month campaign in Greece and Albania or their three years in North Africa.

One of Revelli’s memorable book on the Italian defeat and retreat, La strada del davai, is to this day, his only work available in English as Mussolini’s Death March, Eyewitness Accounts Of Italian Soldiers On the Eastern Front, University Press of Kansas, 2013.

His memoirs and oral histories of the defeat on the Russian front, together with the works of Mario Rigoni Stern, form an enduring literary legacy of one of the most startling Italian wartime catastrophes.

Primo Levi who was good friends with both Revelli and Rigoni Stern wrote in a poem titled, To Mario and Nuto

I have two brothers with lots of life behind them,

Born in the shadow of the mountains.

They learned indignation

in the snows of a distant land,

And they’ve written non-useless books.

Like me, they have borne the sight

Of Medusa, who didn’t turn them to stone.

They haven’t let themselves be turned to stone

By the slow flurry of the days.

Shortly after the Armistice on September 8th, 1943, Revelli joined the Partisans in the mountains above Cuneo. He began his fight against the Nazi-Fascists in Northern Italy and later across the border in South Eastern France. After the war, he started a business as a merchant of iron goods, at first out of necessity and later as a way to avoid being perceived as an intellectual, a writer or a memorialist/historian, all labels with which he felt uncomfortable.

For the rest of his life, Revelli did not stop studying and conducting interviews about the war and its devastating impact. His métier became that of bearing testimony and continuously questioning the past, the facts and their memory. For him the past di not happen once and for all, but continued into the present.

In 1994, almost half a century after the end of the war and his years of combat, Revelli published Il disperso di Marburg.

In this book, while trying to match the legend of mysterious German officer passed down in the local collective memory, to an actual individual, Revelli explores the limits of what historical research can establish, as well as his struggles with his motives and with the restlessness of his conscience.

A “collector” of wartime tales, Revelli in the 1970’s was told about a German officer who in the spring of 1944, every morning, would ride his horse, alone, in the countryside in the province of Cuneo, near San Rocco. The Germans stationed in the area to fight the Partisans were known for brutal reprisals and feared by the population. Yet, this lone rider was perceived as “a good German” who stopped and talked with children and offered cigars to the peasants. One morning the rider is killed. The horse gallops back to the barracks, alerting the Germans, who, curiously after a brief search do not pursue it hunt the lost officer, assume he has deserted, and do not organize the expected reprisal.

Thus begins the author’s search, told in the form of a diary. At first, he composes an oral history of the episode, patiently exhausting all that can be gathered through interviews. Almost everyone who is willing to talk about it has a different recollection. Most agree that he was blond, but some (who claim to have seen him up close) are sure he was around twenty years old, while others swear he looked at least forty. His horse was white for most but brown for others. In some versions of the story, he was killed by the Partisans, in another by a band of stragglers. He was German for some, Ukrainian, Polish or Czech according to other, in short, not even the month when he was killed was certain. Apparently one spring morning he was stopped by a group of armed men, dismounted from his horse and killed. His body was hidden in the dry bed of a river, until months later, when the current took the body away forever.

In the region of Cuneo, and in the very barrack of San Rocco it turns out, there had been at different times, regiments of Ukrainians and Polish soldiers, chosen among the more Aryan looking and often German-speaking ones, who once captured, had been conscripted by the Nazi’s during the retreat from Russia. While according to the Italian Resistance narrative, the Nazi’s —along with the die-hard Fascists of Salo’— were the ultimate perpetrators, in that area, the Nazi’s often left the most brutal repression against the population to the Ukrainian and Poles. In the valleys the peasants still remember, pillages, killings and rape of civilian by often drunk Russian, soldiers.

The more conflicting stories about the “good Nazi” Revelli heard, the more he became intrigued, and with him, the reader.

The author chronicles a long and disquieting search for the identity of the mysterious lone rider, which occupied him from 1986 to 1993.

What makes this painstakingly slow investigation stylistically so engaging, is that it is conducted by a narrator who does not know how and if he will reach a satisfying conclusion. Nor if a “conclusion” is possible, so many years after the facts.

The first phase of the investigation consisted in scouring the area where the facts took place, interviewing anyone who claimed to remember or to have heard something about the story. Displaying his acumen and insight into the trappings of oral testimony, Revelli leaves aside all assumptions, and award credence to anyone who will talk to him. He follows with equal passion all leads, trying his best not privilege the ones that line up with the mental image he is creating for himself of the what may have occurred.

The second phase, consisting of historical research conducted mostly in German archives —Berlin, Freiburg, and Marburg— but also in Italy and as far as former Czechoslovakia and the USSR. Predictably the German State archives are the most complete, yet identifying a fallen officer without knowing the date of death, military rank, battalion or regiment, turn out to be like searching for a needle in a haystack. Further, there was a considerable language barrier. As Revelli did not speak German, he had to rely on researchers and friends who did. This brings into the picture, first and foremost, Christoph Schmick-Gustavus a historian at the University of Bremen (who will turn to be the real “good German” of this story); Carlo Gentile a historian of World War II at the University of Cologne; Shelly Stock Volpi, from the Istituto Storico Della Resistenza of Cuneo, and finally Bodo Guthmüller a professor of Italian literature at the University of Marburg.

Without giving away the details of how the different parts of the puzzle fell into place, eventually, Revelli and his collaborators came up with a name and an outline of a biography. The fallen officer was indeed a German, a sensitive man called Rudolph Knaut, from Marburg, who most likely would have rather taught at the University than participate in the bloodshed of World War II. Documents show that he had fought in France and (like Revelli) on the Russian front before being stationed in San Rocco, near Cuneo. He had been part of the Hitlerjugend (the Nazi youth movement) but not a member of the Nazi Party.

Could this individual fill the space between a fabled “good German” and the terrible associations the term Wehrmacht or SS evoke? Would Primo Levi have placed him in the gray zone?

Revelli does, at last, succeed in giving a name and a biography to the mysterious horseback riding officer, but his curiosity is not quenched. He would like to know more about Knaut’s childhood, friends, aspirations, dreams, in other words, he would like to get to know him. So many years after the war, the possible existence of a compassionate Nazi officer fighting in 1944 against the Partisans, opened up a crevice in Revelli’s conscience.

The more Rudolph Knaut emerged, the more points of contact between him and Ravelli come into focus: both fought on the Russian front, both were caught in a grueling war in foreign lands…

And then the question becomes, can the former Partisan commander Nuto Revelli, conceive of Knaut as anything other than an enemy?

The reader follows step by step, Revelli’s revisiting his convictions and bias in the light of his investigation, bringing to light the many gradations that define the space between the porous concepts of us and them. Chipping away at the archetypal enemy, the Nazi Officer, may have have been a Pole, a Ukrainian, or perhaps even thoughtful peace-loving German, thrown into the war by circumstances.