The Complete Lives of Camp People: Colonialism, Fascism, Concentrated Modernity.

This introduction to the book by the same title published in 2020 by Duke University Press is reproduced here by permission of the author.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, forty years after the end of World War II and as “the Communism was finally defeated,” the “Heidegger affair” burst into the European philosophy. Martin Heidegger (1889–1976), since the 1920s widely recognized as a major and perhaps the greatest philosopher of the twentieth century, became the subject of a painful and often fratricidal debate. Heidegger’s membership in the Nazi party in Hitler’s time, and some of his pro-Nazi speeches from that time, had long been known. But now, a number of new documents came to light, and this at a moment when the world feverishly searched for a new identity. The “Heidegger question” became urgent as a question why a man at the pinnacle of modern thought kept silent about the camps.

The French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard in his intervention in the debate assumed a position that I found close to what I tried to do in this book. Lyotard equaled Heidegger’s silence with the spirit of the time—of our time. Instead of writing “the Jews,” Lyotard wrote “the jews” with a lower- case “j.” “The jews,” he wrote, are both “Jews and non-Jews.” “The jews,” in the spirit of the time, are those “exiled from the inside.”1 One becomes “a jew” when his or her being becomes uncomfortable to the spirit of the time, when he or she stands out, uncomfortably to the rest, as “a witness to what cannot be represented.”2

Minorities, refugees, misery—“this servitude to that which remains unfinished”3—are “the jews.” “The so-called avant-garde,” Lyotard wrote, is “the jews”—as long as it stands firm and thus “asks unanswerable questions.” Even after they are “exiled from the inside,” “the jews” as a specter haunt the spirit, and here the reference is clear. Even after exiled, “the jews” haunt the culture and the civilization from which they had been exiled. “Indeed,” wrote Lyotard, “it is not ‘by chance’ that ‘the jews’ have been made the object of the final solution.”4

Both camps that inspired this book were camps for “the jews.” Theresienstadt (1942–45) was a “ghetto” for the Jews with a capital “J,” in the center of Europe, in the western part of Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia. Boven Digoel (1927–43) was an “isolation camp” in the Dutch East Indies, in Southeast Asia, for “the so-called avant-garde,” the Indonesian rebels who, in late 1926 and early 1927, attempted to overthrow the colonial order. There were non-Jews in Boven Digoel, and many of them were Muslims.

Neither Theresienstadt nor Boven Digoel was Auschwitz—they were not Auschwitz yet. In Auschwitz, all norms of a civilization as it was known, lived, and believed in for centuries had imploded. Unlike the people in Auschwitz, “the jews” of Theresienstadt and Boven Digoel were allowed to live, “privileged until further notice,” in a Potemkin village, a reader might think so—but let him or her imagine!

Trial and length of imprisonment were not a part of the decision to send people to Boven Digoel and Theresienstadt. The people going to the two camps were never allowed to know the trajectory of their lives from the point of their deportation on. They did not know how and whether their “as yet” might end. In Theresienstadt, much closer, intimately close, to Auschwitz, they, often with the greatest effort, rather would not know. In their not- knowing, the camp people of Boven Digoel and Theresienstadt came closer than any other people in modern history to an awe-inspiring closure of everything—that is to say, in Europe as in Asia, closure of the modern.

The people driven to both of the camps were educated, urbanized, and “Westernized,” on the whole, high above the level of the society from which they had been exiled. It was indeed because of their being so (uncomfortably) modern that they were exiled. Neither of the two camps was the nuit et brouil- lard [night and fog]. The modernity did not ebb away in the two camps. Rather, the two camps became a space of the modern crushed into sharp pieces.

Many of the pieces of the broken modern, which “for the time being” were left to the people in the camps, had been merely everyday and often negligible parts of the people’s lives before the camps. In the camps, however, under a possibility of the ultimate implosion of everything, the pieces became untimely. Even trifles became potent and, indeed, the Wunderkabinetts of the trivial now determined the camp people’s lives and the camps as operative communities. It now became vital and could become fatal—how one wore a cap, how one held a spoon, and how one played an étude by Chopin, or recalled it playing. The trivial always has a high rate of surviving existential and historical changes of modern times. Under the unprecedented pressure of the narrow space and time of the camps, the trivial, and the trivial in particular, was “frightened” into an unprecedented import and, indeed, beauty. One could hardly call it a resistance. Rather, the camps became a space of a trivial-sublime.5

There were never more than 2,000 internees in Boven Digoel, while as many as 140,000 internees passed through Theresienstadt. Theresienstadt lasted three and a half years, while Boven Digoel continued for fifteen.

Boven Digoel was a camp for people interned for their politics. Theresien- stadt was a camp for people interned on the basis of their “race.” Theresienstadt was surrounded by walls. Boven Digoel was a clearing in a jungle, at the end of the world; just one step, the people said, and you will fall out. Theresienstadt was set up in an eighteenth-century rococo town, sixty kilometers from Prague, in the middle of the orchards, a weekend destination before the war, especially when the fruit trees were in blossom.

Except for their campness, the two camps had barely anything in common. A comparative study would make little sense. However, the fragments of the broken modern disturb the sense of the time, of our time, and should be studied. They made the two cosmically different camps into one sign, one constellation, possibly enlightening and certainly warning.

Even the story of Hansel and Gretel, and even in the Grimms’ most gruesome first edition, has a happy ending: the witch is punished, father and children sit around the table at home again (the bad mother has died), and everything about the little house in the forest is forgotten. Ludwig Wittgenstein thought that “something must be taught to us as foundation,” but he immediately added that then “doubt gradually loses its sense.”6 When the past is bound by representation, the specter of “the jews” might not haunt us anymore.

Unlike on the way to Auschwitz, the people in these two camps were allowed to take “stuff” with them—fifty kilograms to Theresienstadt, and whatever a particular ship captain permitted to Boven Digoel. People could take their comforters to Theresienstadt, and some internees brought sewing machines to Boven Digoel. People packed the familiar, useful, and useless, in the inhuman haste, having no knowledge of what was ahead of them— under a possibility of the absolute disaster. In the very process of packing, the moment they pushed down the lid of a suitcase, they became camp people as no one in known history before them—“modern,” in the meaning at the root of the word that comes from the Latin modernus, modo, which translates as “just now.”

“The murder,” Theodor Adorno wrote after the war (by “the murder” he meant Auschwitz, but he might as well have written “the auschwitz” with a lowercase “a,” and he might simply write “the camps”), “the murder,” he wrote, “has not happened once, sometime ago, . . . it is happening now,” in the time in which we live, “where ‘Immergleiche,’ the ‘forever same’ endlessly repeats itself.”7 As I wrote, I felt that Adorno was right, except that he stopped in the middle. As the rabbi in Isaac Bashevis Singer’s story says, “Abraham Moshe, it’s worse than you think.”8 I became convinced that, instead of “Immergleiche,” Adorno should write “trajectory,” or still better, “progress.”

“When I start looking at walls,” Samuel Beckett wrote in a letter, “I begin to see the writing. From which even my own is a relief.”9 Every attempt to explain the camps presents an ethical challenge, in the face of which, eventually, a historian has to fail. Writing about the camps can perhaps be justified only when it is “frightened into existence.”10 The most one can do, to say with Beckett again, is to resist “the arrogance of pity,” resist subjecting the lives (and deaths) of “the jews” to “metaphysical simplification,” resist “describing a tree as a bad shadow.”11

Writing about the camps can be justified only when conceived of as a “fugitive analysis,”12 out of breath, looking over a shoulder. In a moment of panic, one might perhaps get a little close to the camp people and the camp lives that were also (at best) on the run.

I might have met some “survivors” of a type Elias Canetti described: “The moment of survival is the moment of power. . . . The dead man lies on the ground while the survivor stands.”13 If I ever met the type, I did not notice. The survivors I met had unsteady memories and unsteady hands. Naturally. They were all late in their lives when I reached them, and life had not always been nice to them, even after the camps let them go. As we talked, I even felt the topic of my research moving toward that of the aging of memory. I became aware that what I was learning was formed very much by my entering a stage of fogginess myself. “We see only what looks at us,” Walter Benjamin wrote.14

Inevitably, I spent more of my time with the survivors’ children and even grandchildren. It neither was less breathtaking or disturbing nor forced me to look less often over my shoulder. As I listened to them, the camps increasingly were being bound by representation. With an increasing anxiety and skill, the specters were being kept away, sometimes by forgetting, other times by mourning. The “études by Chopin” were still in the air, “the jews,” now mostly an immortal community of dead people, were still with us. The camps were still with us, and all around us in fact. In their immensity, and this was new, they sprawled like suburbs: the memory aged in reverse, growing younger, ever more architectural, straight, permitting easy traffic.

I made an effort to learn about Theresienstadt and Boven Digoel in as much detail as possible. In Prague, Theresienstadt (now again Terezín), in Jakarta, Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, or Boven Digoel, I interviewed as many “camp people” as I could still find. I consulted the archive of Boven Digoel, now in Jakarta. Nazis managed to burn most of the Theresienstadt archive in the last days of the war. I went through the public libraries and was given access to some family libraries, even etuis of letters and empty envelopes with stamps often cut away for other collections.

My lifelong career of teaching and writing, mostly on Southeast Asia, as well as my experience of Prague, where I was born and spent forty-five years of my life, appeared in a new perspective as I went on writing about the camps. Always, writers, musicians, and philosophers were precious to me, as I believed they were precious to the civilization in which I lived or wished to live—Franz Kafka, Gustav Mahler, Joseph Roth, Walter Benjamin, Jean Luc Nancy, Pramoedya Ananta Toer, Mas Marco, Tan Malaka. They also appeared to me in a new and unexpected light. They often looked and spoke, and ran, as the camp people did or wished to do—including Heidegger, who became locked in silence by his philosophy as much as his fear.

In the end, this project turned out to be a history of “concentrated mo- dernity,” an unprecedented energy and ethos that emerged in the camps, and radiated out of the camps, like the wise rabbi said, changing our world.

I feel deep gratitude to three anonymous readers for the press, and to the press editors for their uncommon understanding of, and patience with, the unwieldy manuscript.

I have tried my ideas of the camps on teachers and students at Michi- gan in Ann Arbor; Northwestern in Evanston; Berkeley in San Francisco; Columbia and New School in New York; Komunitas Utan Kayu [the Jungle Community] in Jakarta; kitlv, The Royal Institute of Anthropology, in Leiden; and Tokyo and Waseda Universities in Japan. If only the book may be as good, as gracious and helpful, as the people at these renowned places have been!

Nothing with the camps is “merely technical,” neither naming nor spelling. Theresienstadt was called a “ghetto” as often as it was called a “Jewish settlement,” a “camp,” or a “concentration camp.” “Ghetto” in particular was a name forced on the Jews by the Nazis, suggesting the medieval, a place where a still-living Jew might wait until the final solution. The more neutral (kind of) “camp” is used throughout the book, except where other terms are parts of a direct quote. The Czech-speaking internees called the camp Terezín, as the town had been called before it became a camp and as it is called today. The internees from the other language regions, however, generally used the German “Theresienstadt,” which was also the camp’s official designation. “Theresienstadt” is used in the book, except when “Terezín” appears in direct quote.

In 1972, the Indonesian government decreed a language reform, substituting “u” for “oe,” “c” for “tj,” “j” for “dj,” and “y” between vocals for “j.” Like the military, right-wing and oppressive government was unpopular and resisted, so many people, including virtually all the Boven Digoel people, kept their names with their pre-1972 spellings. This is the way their names are spelled in this book, except when the new spelling is used in direct quote. The local names are given in the new spelling for the comfort of current maps users especially.

Boven Digoel was called a “camp,” an “isolation camp,” and also a “con- centration camp,” until about 1940, when the last term was deemed by the Dutch officials to be too discredited. “Tanah Merah” was also often used, meaning “red soil,” not “The Red Land” or even “The Land of the Reds,” as might seem logical or even natural. “Boven Digoel” is used with few excep- tions in the book, and in the old spelling, as it appears almost universally in documents and memories. “Boven Digoel” is still today the official name of the place where the camp stood.

Some of the Theresienstadt people started to use Hebrew names after the experience of the camps: Eva became Chava; Vlasta became Nava; Jindra became Avri. The immensity of this change, like that of the others, could not be adequately conveyed, only respectfully transcribed.

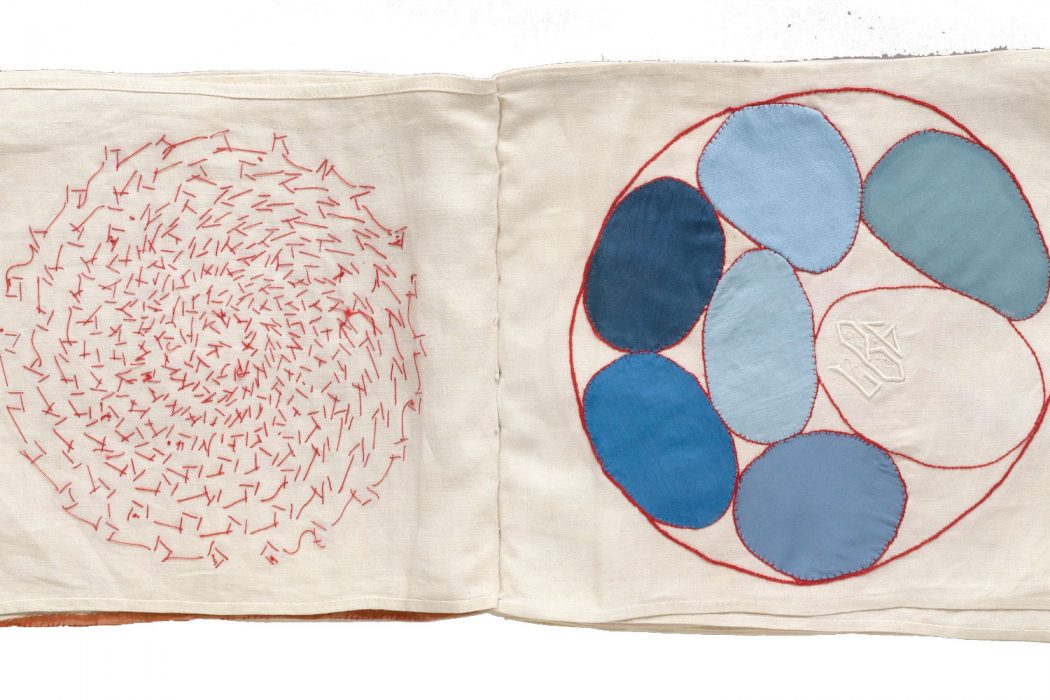

Image: Louise Bourgeois, Unfolding Portrait