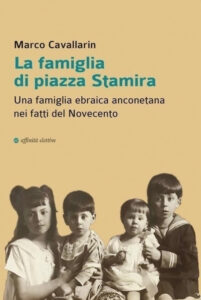

Marco Cavallerin’s La famiglia di piazza Stamira (Affinità Elettive, Ancona, 2023. In Italian), a title that refers to the family’s ancestral home in Ancona, is a captivating read that packs a wealth of information, photographs, documents, letters, and diary entries, tracking the lives of the Sacerdotis a Jewish family from Ancona, from the early decades of the XX century to the present. Neither genealogy, chronicle, or historical account, the book attests to Cavallarin belief in the value of unfiltered first-person accounts.

Unlike a historian, the author relies principally on interviews or written testimony by the different family members, without the pretense of “objectivity.” What emerges is a fascinating, highly personal, and intimate group portrait of several generations of a family that spreads out of Ancona to Rome, Ferrara, Milano, Lago Maggiore, Ashkelon, New York, and beyond, against the background of the Fascist racial laws, persecution, emigration by aspiration or necessity. We learn about each family member, their professional successes and travails, love, marriage, and ambitions, but above all, we glimpse into the tonality of their individual lives.

Unlike a historian, the author relies principally on interviews or written testimony by the different family members, without the pretense of “objectivity.” What emerges is a fascinating, highly personal, and intimate group portrait of several generations of a family that spreads out of Ancona to Rome, Ferrara, Milano, Lago Maggiore, Ashkelon, New York, and beyond, against the background of the Fascist racial laws, persecution, emigration by aspiration or necessity. We learn about each family member, their professional successes and travails, love, marriage, and ambitions, but above all, we glimpse into the tonality of their individual lives.

Ancona, particularly pre-war Jewish life in Ancona, looms large in the family memories and nostalgia: its specific turn of phrases, homes, cuisine, costumes, and traditions. The bulk of the narrative stems from the very different lives of the four Sacerdoti siblings born between 1909 and 1917. Sara Sacerdoti, born 1909, made aliyah out of love for her husband Nello and, even in Ashkelon, carried an unmitigated longing for Ancona into her old age. Despite being, in his youth, a prankster and a daredevil, Enzo Sacerdoti became a pillar for the family. In the dark years of persecution, he joined the partisans and went to great lengths to hide and protect his parents. And Vittorio Emanuele Sacerdoti, a doctor born in 1915, practiced in Rome and, during the Nazi occupation, continued to practice under a false name at the Ospedale Fatebenefratelli. And, of course, their lovers, spouses, children, and cousins rap the reader in a complex network of relations along the winding paths of their memories.

At every page and turn in the narrative, one feels the love and empathy with which the author has researched, connected, and brought to life the trajectories of a family that are both unique and representative of Italian Judaism at large.

Some examples will convey the vividness of the stories in this book. Without ever diminishing the brutality of the Regime, here is Vittorio Sacerdoti’s ironic eye describing his days as a student before the racial laws: […] “They also forced us to do pre-military service. I was hired for air defense, but all air defense consisted of was a yellow band with “air defense” written on it. At the university, we had to do pre-military when we really needed to study and didn’t have time to do those exercises, which weren’t exercises at all.” In his third year at medical school, Vittorio is already working at the hospital in Ancona: […] “We were held in high regard by the chief physicians and by the assistants of all ranks. Those doctors were keen to pass on their knowledge to the young. […] One fine day, the director of the hospital, who was a true fascist, a “squadrista”, who went around in high boots, sent for me. He told me with rude words: “From today onwards, you will no longer come here. You are an enemy of the homeland. Go away, never let me see you again.” I would have spat in his face, but I didn’t. Yet I didn’t lose my dignity, I didn’t lower my eyes, and I looked him straight in the face.”

There are many examples of the anguish of the many separations. Soon after the birth of Ariel, their first son, Sara Sacerdoti, and her husband, Nello Castelbolognesi, decided to make aliyah. Sara’s father, Sabato Sacerdoti, was heartbroken, particularly for missing out on his grandson’s childhood: “The sun—he said—you are taking the sun away from me!”

Vittorio recalls their departure from Ancona: “They left by train, like in a movie, towards the unknown. They boarded in Brindisi. Sara left with Nello, her husband, and little Ariel, who had been born a few months earlier. They went to the kibbutz of Givat Brenner, where they had to live with a rifle in one hand and a shovel in the other. Sara adds details: “When we arrived, in the spring of 1939, there was no harbor in Tel Aviv, the ship stopped offshore, and a lifeboat took us ashore. I was pregnant with Asher and held Ariel, who was still a baby. We arrived with the kamsin, 40 degrees centigrade. I had a large belly and dressed in wool like in Italy, where it was still cold. It was April 1, the eve of Pesach. Upon disembarking, many bowed and kissed the land of Israel.”

The story feels and indeed is very personal for the author, Marco Cavallerin, who is the loving husband of Patrizia Ottolenghi, the daughter of Cesarina Sacerdoti. This personal connection adds a layer of intimacy and trust to the narrative, making it a more engaging read for the audience.

Through the lens of the Sacerdotis and the families they married into, the reader gets a series of first-person accounts that provide a kaleidoscope view of the Italian Jewish experience in the XX centuries. The accounts are, at times, touching, romantic, humorous, dramatic, heroic, and tragic. Exploring bonds within the family, strength, courage vis-a-vis the hardships, hopes, and aspirations, the book transcends the specifics of each family member to touch upon the experiences of several generations.

Image: Cesarina Sacerdoti and friends, Bolognola, 1934 ca.